Ebbets Field (Brooklyn, NY)

This article was written by John G. Zinn

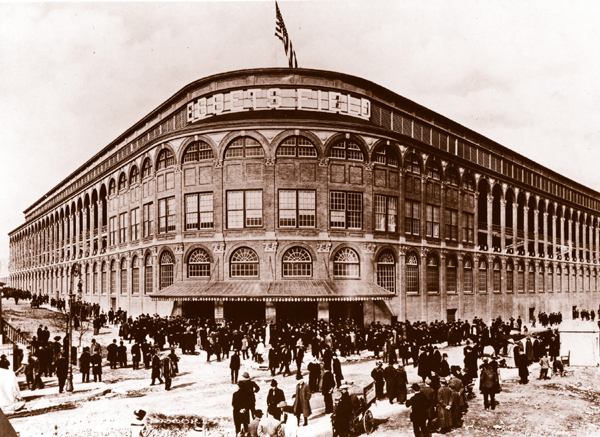

The iconic main entry of Ebbets Field was located at the intersection of Sullivan Place and Cedar Street (later renamed McKeever Place). (Photo: SABR-Rucker Archive)

On an October afternoon in the 1950s, while the Dodgers prepared for the first game of the World Series, an elderly man walked into Ebbets Field. On the surface it seemed like business as usual; Brooklyn had dominated the National League throughout the decade with regular appearances in the fall classic. Sadly, however, this time nothing was the same. Not only was the game being played in Chicago, the Dodgers, on October 1, 1959, called Los Angeles home. Little is known about this Dodgers fan, other than that he appeared to be about 70 and came to Ebbets Field regularly to sit and stare at the iconic, but now superfluous scoreboard.1 If, however, the man was a lifelong Dodgers fan, he had witnessed a lot of the club’s history including watching the 1899 and 1900 championship teams play at the club’s home field – Washington Park.

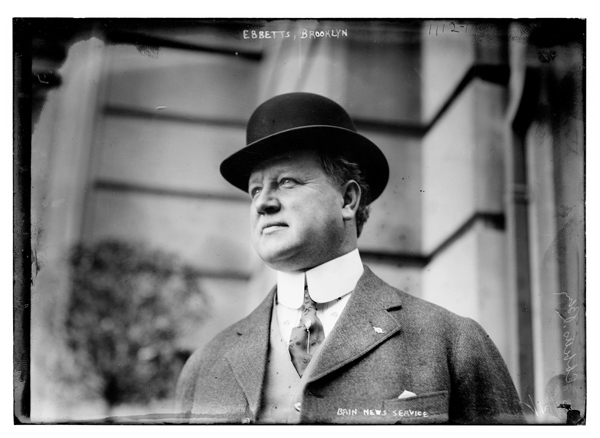

By late 1911, however, our somewhat imaginary Dodgers fan had little reason for optimism. Not only was it over a decade since the Dodgers’ last pennant-winning season, Brooklyn fans had endured nine consecutive second-division finishes. And if the team’s performance offered little incentive to attend games, Washington Park itself was no longer a state-of-the-art ballpark. Beginning with Shibe Park in Philadelphia in 1909, Dodgers fans could only read and dream about a new generation of ballparks being built throughout the major leagues. Little did they know that Dodgers owner Charles Ebbets was about to give them and Brooklyn one of baseball’s most beloved ballparks.

Unlike the fans, however, the media knew the Squire of Flatbush was up to something. In their holiday mail was an invitation to a January 2, 1912, dinner at which, according to a line highlighted in red, “A very important piece of news” was to be announced.2 While some speculated that Ebbets would announce improvements to Washington Park, reporters from Brooklyn’s four daily newspapers correctly concluded that his announcement was about a new ballpark.3 Recognizing that the people of Brooklyn had loyally supported a losing team, the Dodgers owner told his audience the fans were “entitled to the new park.”4 While the news wasn’t a surprise to the reporters, William Granger of the Brooklyn Citizen claimed “not one [guess about the location] was even close.”5

Ebbets declared that he had found the right location on 5.7 acres in the southwest part of Crow Hill in the Flatbush section of Brooklyn which was previously known as the Pigtown garbage dump. While the area was described as “farmlike” with few buildings, it was also home to the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences (now the Brooklyn Museum) as well as the Consumer Park Brewery and the Hygienic Ice Company. It took a few years, but a surge in housing construction that lasted through the 1920s would bring families with children to the area.6 Bounded by Bedford Avenue, Cedar Place, Montgomery Street, and Sullivan Place, the site was reportedly so accessible by mass transit that the Brooklyn Daily Eagle jokingly claimed, “Even a bigamist could ask no more avenues of escape or approach.”7 Just acquiring the land was no small accomplishment. Ebbets had to buy 25 to 30 parcels in great secrecy because if word got out, the prices would have been driven up well beyond his limited financial means.8

On this site, Ebbets intended to build a standard Deadball Era ballpark with a double-deck steel and concrete grandstand running from the right-field corner to third base, supplemented by concrete bleachers from third to the left-field foul pole. Although the original plans included bleachers in center field which would have increased the seating capacity to 30,000, no seats were built in fair territory, reducing total seating to about 24,000.9 While the trapezoid shape of the land mandated a short 301-foot right-field fence, left (419 feet) and center (507 feet) would have the standard dimensions of the period. Of special note was the rotunda, intended as the primary entrance to the park (although congestion would quickly lead to the opening of two additional entrances). Made of marble, the rotunda featured a chandelier with 16 lights “representing so many baseballs,” all “suspended from arms in the shape of bats.”10 Before Ebbets could turn his attention to building his new ballpark, however, it had to have a name. While Ebbets Field was suggested from the outset, the Brooklyn owner wisely left the decision to the sports editors of the four Brooklyn daily newspapers. In what may have been a preordained process, they chose Ebbets Field and so it remained throughout its existence.11

Brooklyn fans, however, were probably more concerned about when the dream ballpark would become a reality. Understandably caught up in the excitement, Ebbets hoped for an already “doubtful” Flag Day (June 14), but was “positive” fans would enjoy games there by August 27, the anniversary of the Revolutionary War Battle of Brooklyn.12 However, any even slightly objective observer who visited the site would have concluded that a 1912 opening was unlikely. Not only was there a large hole described as either “the subway to China,” or “a Miniature Grand Canyon,” the Bedford Avenue side was as much as 16 feet higher than the Sullivan Street side.13 Clearly significant site work was necessary; it depended on the weather, something Ebbets couldn’t control, and brutal cold delayed site preparation until early March.14

These delays were only the beginning of the problems Ebbets encountered building his new ballpark. Unforeseen issues like a new sewer, more bad weather, and labor problems doomed any possibility that the ballpark would open in 1912.15 Far more ominous, however, was that due to Ebbets’ poor financial planning, he was in danger of running out of money long before the ballpark was finished. By August 1912, the Brooklyn owner was reduced to asking for loans from his fellow owners, most of whom were not receptive. With no alternatives left, Ebbets faced the inevitable and sold 50 percent of the Dodgers (and Ebbets Field) to Steve and Ed McKeever in order to finish the project.16 Equal ownership meant decision-making by consensus, which seems to have worked so long as all three men were alive, but not so well afterward. Such problems were, however, well in the future and finally, in April of 1913, some 15 months after the announcement, Ebbets Field was ready to host its first game.

A visionary sports executive, Charles Ebbets was the majority owner of the Brooklyn Dodgers from 1897 until his death in 1925 and served as club president from 1898 to 1925. (Photo: Library of Congress)

Since just building Ebbets Field was more than a little complicated, it was only fitting that scheduling the opener was also difficult. Under the National League’s rotating schedule, created by Ebbets himself, the Dodgers were to open the 1913 season on the road. Thanks, however, to the efforts of Tom Rice of the Eagle and the somewhat grudging consent of Ebbets’s fellow owners, Brooklyn was awarded a special opener on April 9. By that point, however, Ebbets had preempted the National League opener with two exhibition games against the New York Yankees.17 If fans needed any further encouragement to attend the April 5 exhibition game, it was provided by “one of the nicest little Spring days the oldest inhabitant of Flatbush could remember.”18 The combination of a new ballpark, a new season, and a nice day produced a vast throng that packed subway and trolley lines. Nor was mass transit the sole means of access. So many came by auto that some of the more sheltered local residents thought “[t]here ain’t that many machines [cars] made.”19 If the limited parking that hampered Ebbets Field’s future was a problem the day it opened, no mention was made in the media.

After enduring packed subway cars and seemingly endless traffic, fans anxious to see the new ballpark encountered further delays getting to the ticket booths in the rotunda. Once up the ramps, however, they saw the field for the first time, anticipating thousands who never forgot their first view of Ebbets Field. Less fortunate were the estimated 5,000 to 10,000 potential ticket buyers who couldn’t get in, missing not only a first look at the new ballpark, but also a dramatic Brooklyn win in the bottom of the ninth.20 The media heaped praise on the new ballpark, with the Brooklyn Daily Times claiming that “Nothing but praise was heard for the new stadium,” while the Eagle gushingly proclaimed it “the greatest ball park in these United States.”21 Those who attended the opening made a wise choice since four days later, only 10,000 braved 37-degree temperatures to witness a 1-0 loss to Philadelphia in a blessedly short 90 minutes.22 The frigid conditions did not, however, stop the chorus of praise for the new ballpark, which the Philadelphia Inquirer called “an athletic inclosure second to none.”23

Although the 1913 Dodgers were destined for another second-division finish, the new ballpark attracted over 100,000 more admissions.24 Attendance fell over the next two seasons, however, primarily because of head-to-head competition with the Federal League’s Brooklyn franchise (even though the Dodgers were finally becoming competitive). By 1915 Brooklyn had not only reached the first division, Ebbets Field hosted its first pennant race. The team’s third-place finish sparked plenty of optimism about 1916, which was richly rewarded with the Dodgers’ first pennant since 1900 and the team’s first appearance in the modern World Series. Unfortunately for Charles Ebbets, the on-the-field success didn’t consistently translate into ticket sales, and some important September games drew “pitifully small” crowds of 2,000 to 3,000.25

Probably trying to recover the lost revenue, Ebbets unwisely raised prices for World Series tickets, which led to crowds well under capacity for both games played at Ebbets Field.26 Dodgers fans might have been more understanding had they known that unlike Boston Red Sox owner Joseph Lannin, Ebbets did not pursue a suggestion to shift Brooklyn’s home games to a larger ballpark like the Polo Grounds.27 Those who did attend the first World Series game at Ebbets Field saw a Dodgers victory, but the following day, the Red Sox quickly overcame an early Brooklyn lead to win the game and take control of the Series.

Before the Dodgers had a chance to defend their 1916 National League pennant, the United States entry into World War I wreaked havoc with major-league baseball. The Dodgers felt the full effect in 1918 when, although the club finished fifth, it was dead last at the box office, drawing under 84,000 fans, a decline of over 80 percent from 1916.28 Facing the government’s work-or-fight order, the owners ended the season early and by mid-September, Ebbets Field was a storehouse for war-related material.29 While it appeared there would be no 1919 season, the November 11 Armistice restored not only peace, but major-league baseball. There was so much uncertainty about the coming season, however, that the owners chose to play an abbreviated 140-game schedule.30 Even though fewer games were played at Ebbets Field that season, the big news was that some were played on Sunday.

Ever since the team’s founding in 1883, Dodgers fans whose only day off was Sunday were prevented from attending games by the so-called “blue laws,” which prohibited baseball games with an admission charge on the Sabbath. From 1904 to 1906, Charles Ebbets unsuccessfully tried various ploys to get around those restrictions.31 When the wartime environment facilitated reopening the issue in 1917, Ebbets tried again, only to be arrested and convicted of breaking the Sunday baseball laws.32 Finally in April of 1919, legislative action removed the prohibition, and less than a week later, Ebbets Field hosted its first Sunday game, the first of 13 that season. Although there was little advance sale, about 22,000 attended, more than either of the 1916 World Series home games.33 Finally baseball at Ebbets Field was available to everyone in Brooklyn.

Nor was the large Sunday crowd a one-time thing, helping 1919 attendance reach almost 361,000, the second highest in the ballpark’s brief history. A year later, Ebbets Field hosted 19 Sunday games, which, along with a pennant-winning team, drove attendance to an unprecedented 809,000, second best in the National League.34 However, not everyone who passed through the Ebbets Field turnstiles in 1920 was an unquestioning loyalist. As the pennant race headed into September, Tom Rice of the Eagle claimed that the team played better on the road because of “a certain sort of Brooklyn fans,” who were relentlessly critical without ever offering “a word of encouragement.” Hard as it may be to believe, both Ebbets and manager Wilbert Robinson agreed with Rice, warning the not-so-faithful that they could cost Brooklyn the pennant.35

But sufficient fans mended their ways and Ebbets Field hosted its second World Series, against the Cleveland Indians. Fortunately, there was no repeat of the dispute over ticket prices and large crowds saw their Dodgers win two of the first three games before being swept at Cleveland in the next to last best-of-nine fall classic. Although the team’s performance fell off during the next three seasons, Brooklyn fans continued to flock to the ballpark for the rest of Charles Ebbets’ tenure. By 1924 the Dodgers were once again in the heat of the pennant race and finished a close second before record-setting attendance of almost 819,000.36

Attendance mattered more in Ebbets Field’s early years because owners had few sources of revenue beyond ticket sales. One way of generating additional revenue was hosting other events, athletic and otherwise, when the Dodgers were not playing at home. Even before he started renting his ballpark, however, Ebbets opened the new facility rent-free for a field day for orphans and later admitted local students at no cost to watch their peers compete at baseball and track. Although the events netted Ebbets no revenue, they gave the community a greater sense of ownership of the new ballpark. However, Ebbets also wasted little time in renting his ballpark for other events. College baseball was played there during the inaugural season, followed two years later by boxing and eventually soccer, which actually outlasted the Dodgers. Nonsporting events included opera in 1925 and a 1926 wedding of two orphans sponsored as a fundraiser for a local hospital.37

One of the earliest alternative sources of revenue was football, probably because Ebbets had rented out Washington Park for the same purpose. College football was played at Ebbets Field as early as 1917 and continued through the 1940s. The most important college game at Ebbets Field was the 1923 Army-Notre Dame game, played in Brooklyn because the World Series was at the Polo Grounds. Professional football got started at Ebbets Field in 1926 and continued through 1948 with the aptly-named Brooklyn Dodger football teams enjoying only limited success. More historically significant was the first televised football game in 1939, only a year after Ebbets Field hosted a similar milestone for major-league baseball. Far more important to the story of the Brooklyn ballpark, however, were the more than 200 high-school football games played there over a period of 40 years beginning in the ballpark’s inaugural season. Featuring at least a dozen schools including historical rivalries like Erasmus-Manual (they played 41 times at Ebbets Field), these games gave countless players, cheerleaders, and band members the chance to perform on the same field as their baseball heroes.38 The shared experience was yet another link between Brooklyn and Ebbets Field.

By 1925 the Dodgers and Ebbets Field were “one of the most valuable properties in baseball.”39 It was a testament to Charles Ebbets’ years of hard work, but sadly those accomplishments would not long survive Ebbets’ death on April 18, 1925. Standing in a cold rain at the funeral, Ed McKeever caught a cold that turned into pneumonia and he, too, was dead by month’s end.40 Suddenly 75 percent of the Dodgers and Ebbets Field were owned by the Ebbets (50 percent) and Ed McKeever (25 percent) estates. Far more serious, however, was the fact that this was not simply a transfer of ownership from one generation to the next. Instead it was a sea change from owners engaged in baseball as a business to heirs/investors whose primary concern was receiving regular dividend payments. Ebbets’ ownership interest was divided into 15 parts while Ed McKeever, although he was childless, had supported so many relatives that his estate had even more (18).41 It was a situation ripe for disaster, exacerbated even further by Steve McKeever’s ongoing feud with manager Wilbert Robinson.42

While these problems were probably not the sole cause, the club dropped to the second division in 1925 and stayed there for the next four seasons. Attendance-wise, however, the team continued to draw well, but with so many mouths to feed, dividends quickly exceeded profits. From 1925 to 1929, the Dodgers earned net profits of just over $474,000, but paid out $684,000 in dividends.43 Not only was there less money to acquire players, there were also little or no funds for repairs and renovations at Ebbets Field, not to mention expanding the park’s limited seating capacity. Steve McKeever raised this concern as early as 1928, but said the rest of the board “seemed reluctant” to take any action, a stalemate that continued until the 1930 season finally forced the issue.44

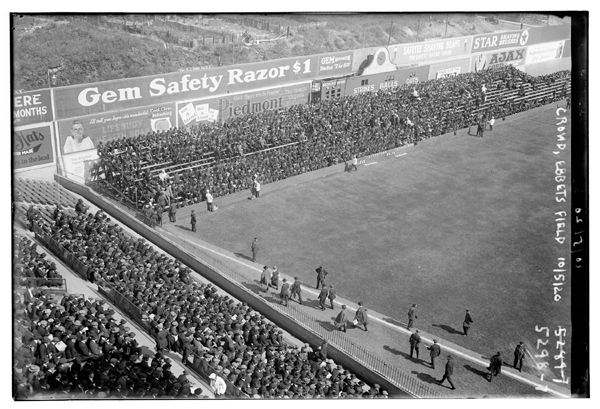

The 1920 best-of-nine World Series opened on October 5 at Ebbets Field, where temporary bleachers were erected on the outfield. (Photo: Library of Congress)

Perhaps the worst nightmare of pre-TV-era owners was inadequate seating capacity, which became a major problem in Brooklyn in 1930 when the Dodgers contended for the pennant all season long before finishing fourth. The good news was that the team drew over a million fans for the first time and realized a profit of almost $427,000, exceeding dividends paid for the first time since 1926.45 The bad news was that on at least a dozen occasions, 5,000 to 10,000 fans couldn’t buy tickets because of the limited seating capacity.46 Every one of those lost admissions would have gone straight to the bottom line, available, among other things, to help pay for the sorely needed expansion. Although still stymied on that front, Steve McKeever made one badly needed (according to him) improvement – the-20-foot screen on the top of the right-field wall. According to the Eagle, McKeever “has been worrying all summer lest a Brooklyn line drive descend abruptly on the bonnet of some elderly lady across that famous thoroughfare Bedford Avenue.”47

The possibility of adding more seats was facilitated when the “Warring factions” on the board reached some compromises, including adding a neutral fifth board member appointed by National League President John Heydler to break deadlocks.48 In this improved environment, the expansion of Ebbets Field moved forward, but at a slow pace. Key to Steve McKeever’s plan, which would supposedly have expanded the seating capacity to 50,000 to 60,000, was getting New York City to move Montgomery Street (behind the left-field wall) to the other side of the current thoroughfare onto land owned by the Dodgers. This would have facilitated the construction of a new triple-decker stand in left field while maintaining the original outfield dimensions.49 In spite of rumors that the expanded ballpark would be renamed Brooklyn Stadium, McKeever insisted that it would continue to be called Ebbets Field.50 Sadly, the city refused to cooperate and the new stands, now reduced to two levels, had to be built on the existing site, encroaching into the outfield, moving deepest center field over 100 feet closer to home plate. Over the years the distance down the left-field line would be decreased to 343 feet while the distance to center field would also be reduced a little bit more. The revised plans added only about 9,000 new seats, not the 25,000 to 35,000 envisioned by McKeever in 1928. According to Philip Lowry in Green Cathedrals, Ebbets Field’s seating capacity would peak at 35,000 in 1937 and drop to just under 32,000 during the ballpark’s last season.51

Even with the obvious financial advantages and the approval of 80 percent of the shareholders, the project became bogged down in legal issues. At the root of the problem was not opposition by the various heirs, but the fact that 75 percent of the stock was owned by estates, some of whose beneficiaries were infants represented by guardians.52 In the end, approval was sought from the surrogate’s court, which ruled that the real issue – mortgaging the property, not the expansion itself, was a business decision, not a legal issue.53 Armed with that somewhat less than definitive support, the club simultaneously broke ground and began construction on February 16, 1931, on a project estimated to cost $450,000.54 Unlike the original construction, the expansion proceeded more or less on schedule, and all of the new seats were available by the last weekend in May.55 Since these were the years of the “Daffiness Boys,” it was probably appropriate that the first player to reach the new center-field seats was the club’s leading eccentric, Babe Herman.56

But the timing of the expansion couldn’t have been worse. In a twist worthy of a Dickens novel, as soon as the seating capacity was increased, it was no longer needed.57 The Dodgers on-the-field performance declined; along with the Depression this sent attendance plummeting by over 344,000 in 1931. Nor was that the end of the downturn as attendance dropped below 500,000 in 1934 and stayed there through 1937.58 Unsurprisingly, regular profits became regular losses, further exacerbated by the payment of $125,000 in dividends. From 1932 to 1937, the team lost $667,000 and by the end of the period, the ballclub was deeply in debt and at risk of having the National League take over the franchise and Ebbets Field.59 Naturally the ballpark also suffered and by the late 1930s Ebbets Field badly needed painting and repairs, while the beloved rotunda was “covered with mildew.”60

But even though it wasn’t obvious in 1938, better days were coming, beginning with the arrival of future Hall of Fame members Leo Durocher and Larry MacPhail. Although Durocher came first, acquired in a late 1937 trade, it was MacPhail who had the most immediate impact beginning in early 1938.61 Described as having “a large and speckled reputation,” the flamboyant Dodgers leader was a breath of fresh air, and Ebbets Field, which had become “a monument to peeling paint and mildew,” was the immediate beneficiary.62 After persuading the Brooklyn Trust Company to lend over $300,000 to the already debt-burdened club, MacPhail spruced up the inside of the ballpark and installed lights for night games. A year later, the Brooklyn executive began broadcasting Dodgers games on the radio, a step magnified even further by hiring the soon to be legendary Red Barber as broadcaster.63

MacPhail also improved the on the field product by upgrading the roster and hiring Durocher as manager for the 1939 season.64 Perhaps climbing more rapidly than might reasonably have been expected, the Dodgers moved from seventh place in 1938 to third in 1939 and then won the club’s first pennant in over two decades in 1941. And the Dodgers faithful responded to the club’s rapid rise, driving 1941 attendance to 1.2 million, almost double that of 1938. Even more impressively, Brooklyn led the major leagues in attendance in both 1941 and 1942, outdrawing both the Yankees and Giants.65

Although Dodgers fans were disappointed by the 1941 World Series loss to the Yankees, things were clearly looking up at Ebbets Field. Among those attracted by the team’s newfound success were some of the Dodgers’ legendary fans, beginning with a “plump, pink-faced woman with a mop of stringy gray hair” named Hilda Chester.66 After Chester’s constant yelling contributed to a heart attack, she substituted banging a ladle on a frying pan until the Dodgers players gave her the famous cow/school bell as a somewhat less grating alternative.67 Nor was Hilda content to limit herself to cheering from the sidelines; she famously used Pete Reiser to deliver a note recommending a pitching change to Durocher, a missive the Dodgers skipper mistakenly attributed to Larry MacPhail.68

Even though she was unaccompanied, Chester probably held her own in the noise department with the Dodgers’ most famous group act, the Brooklyn Sym-Phony. Although the band played at Ebbets Field as early as 1937, they didn’t attract media attention until the 1941 pennant race.69 Although not noted for the quality of their music, the group earned praise from Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Doris Kearns Goodwin for their “very creative” song selection intended to annoy opposing players and umpires.70 In addition to disturbing the opposition and fans who just wanted to watch the game, the band also ran afoul of Local 802 of the American Federation of Musicians in 1951, resulting in a temporary ban on their performances. To fill the void, Walter O’Malley, although not noted for his sense of humor or generosity, gave free admission to any fan bringing an instrument to an August 13 game. Over 2,400 participated, including seven men who dragged/pushed a piano. According to Milton Bracker of the New York Times, the so-called musicians “tooted, fiddled, banged, boomed, squeaked, tinkled and clanged” to the point that the evening might better have been labeled “music depreciation night.”71 Also providing musical accompaniment, but of far better quality, was Gladys Goodding, who began playing the organ at Ebbets Field in 1942.72

As with all ballparks, advertising was a regular feature at Ebbets Field, from the Bull Durham tobacco ad to the Schaefer Beer sign on top of the scoreboard. Most famous of all was the Abe Stark sign, which actually took two different forms. The original replaced a Bull Durham tobacco advertisement and covered about 150 feet of the right-field wall from top to bottom. Stark, the operator of a Brooklyn clothing store, offered a free suit to any player who hit it with a batted ball. Reportedly many did, prompting Stark to opt for a smaller version when the new scoreboard was installed during the 1931 expansion. With the sign located below the scoreboard and only three feet high, but 30 feet long, fewer players achieved the feat, beginning with Mel Ott that very first season. Later Carl Furillo stood in front of the sign, saving Stark countless free suits to the point that Ralph Kiner and his teammates joked that Stark should have given Furillo a free suit in gratitude.73

While Dodgers fans enjoyed another good season in 1942, the United States’ entry into World War II eventually took its toll. The on-the-field product became substandard and attendance declined by almost 400,000 admissions from 1942 to 1943 and stayed below 700,000 through 1945.74 Wartime rationing also limited repairs to Ebbets Field itself, which was graphically illustrated on August 6, 1944, when a Boston Braves home run went through a hole in the right-field screen that hadn’t been repaired because of a shortage of building materials.75 Far more significant, however, were some leadership changes. Not long after the 1942 season, Larry MacPhail left the Dodgers and was replaced by Branch Rickey. Although far less flamboyant, Rickey was even more competent, but was also, according to John Drebinger of the New York Times, “a man of strange complexities, not to mention downright contradictions.”76 Also on the scene was Walter O’Malley, an attorney representing the Brooklyn Trust Company, which lent the team money and also was the trustee for the Ebbets and McKeever heirs.77

In spite of the wartime problems, the Dodgers’ financial situation had improved sufficiently for new ownership to finally buy out the heirs of Charles Ebbets and Ed McKeever. The latter group went first in late 1944, followed by the Ebbets heirs in August of the following year. Naturally, since it was the Dodgers, it was a complicated transaction, but once the ink was dry, Rickey, O’Malley, and the less well-known, but wealthier, John Smith were majority owners of the Dodgers. Still remaining in a minority position were Steve McKeever’s heirs.78

During the five years or so that O’Malley and Rickey ran the Dodgers, the latter concentrated on baseball operations and gradually built the legendary lineup fondly remembered as the Boys of Summer. Of that group, one made history at Ebbets Field, not just baseball history, but American history. When Jackie Robinson ran out to first base on April 15, 1947, he not only became the first African American to play major-league baseball in the twentieth century, but also ushered in a new phase in the civil rights movement. If, however, the local media realized they were witnessing history, they had little to say about it. Arthur Daley of the New York Times called Robinson’s debut “quite uneventful” while the Eagle and the Daily News paid little attention. Nor was the event a hot ticket as the crowd fell short of a sellout. Noteworthy, however, were the African Americans, who made up somewhere between one-third and one-half of the crowd and didn’t need to be told something special was going on.79 Any perceived indifference to the significance of Robinson’s joining the Dodgers would quickly fade as those who witnessed his “dignity” in the face of regular abuse had, in the words of Pulitzer Prize-winning biographer Robert Caro, “to think at least a little about America’s shattered promises.”80

The Ebbets Field grandstand is packed with fans during Game 3 of the 1941 World Series between the Brooklyn Dodgers and New York Yankees. (SABR-Rucker Archive)

While Robinson was the first African American to wear a Dodgers uniform, he was hardly the first to play at Ebbets Field. That distinction went to the Bacharach Giants, who called the Brooklyn ballpark home from 1919 to 1921. After 1921, it wasn’t until 1935, when Abe Manley and his wife, Effa, arranged for the Brooklyn Eagles to play there, that another professional Black baseball team called Ebbets Field home. Although the Eagles were the sole Black club to have a major-league ballpark for their home field, the arrangement was unsuccessful largely due to competition not only from New York’s major-league clubs, but also from Brooklyn’s many semipro teams. The Eagles left Brooklyn after one season, shifting to Newark, where they enjoyed so much success that in 2006 Effa Manley became the first woman inducted into the Baseball Hall of fame. Professional Black baseball returned to Ebbets Field briefly in the postwar years, only to be supplanted by Rickey and Robinson.81

When Ebbets Field was built, Charles Ebbets took special pains to have a high-quality playing surface.82 He was clearly successful, since years after his death many players, both Dodgers and the opposition, had good memories of the field.83 They also remembered the limited foul territory which, according to Carl Erskine, meant the players could hear almost everything said in the stands. So close were the fans that Randy Jackson said batting practice could be dangerous for fans who didn’t pay attention.84 Visiting players were less appreciative of disgruntled fans who sometimes sprayed ink on the clothing of players who didn’t respond positively to an autograph request.85

The transition to the great ballclub of the postwar era began with the 1946 return of Pee Wee Reese from military service and the debut of Carl Furillo that same season. In addition to Robinson, Duke Snider and Gil Hodges played for the Dodgers in 1947, followed a year later by Roy Campanella, Billy Cox, Carl Erskine, and Preacher Roe. Further bolstering the pitching staff were the additions of Don Newcombe (1949), Clem Labine (1950), Joe Black (1952), and Johnny Podres (1953). Also playing an important role in the Dodgers’ success were Andy Pafko (1951) and Jim Gilliam (1953). Leo Durocher was the manager at the beginning of the postwar period before running afoul of Commissioner Happy Chandler and Rickey. Burt Shotton filled in for Durocher in 1947 and became his permanent replacement in 1948. When Walter O’Malley bought out Rickey after the 1950 season, he replaced Shotton with Charlie Dressen before turning to Walter Alston in 1954.86

At some level the manager may not have mattered, since fans at Ebbets Field enjoyed one successful season after another. In the 12 seasons from 1946 to 1957, Brooklyn won six National League pennants and finished second four times, twice after tying for the regular-season lead. The worst performances were two third-place finishes, the last in 1957, the team’s final season at Ebbets Field. The six pennants led to 20 World Series games in Brooklyn in which the Dodgers compiled an 11-9 record, including winning 8 of the last 10 Series games played at Ebbets Field. The team was far less successful in the two playoff series, losing both games played in Brooklyn. During this period Ebbets Field also hosted the 1949 All-Star Game, won by the American League, but more significantly the first time African American players took part. Although the Dodgers’ on-the-field success was overshadowed by the Yankees’ World Series dominance, Bill James believes only the 1906-10 Cubs and the 1942-46 Cardinals “accomplished more [in the National League] than the Dodgers of 1952-56.” Over that five-year period, the team averaged 97 wins per season, finished first four times and second once.87

Understandably, this is the same period when fans enjoyed so many unforgettable experiences at Ebbets Field. For some it began when they came out of the subway to the aroma of fresh-baked bread from the local Bond Bread factory. As fans followed the crowd to the ballpark, the smell of beer, cigars, peanuts, and hot dogs blended with the bread and produced a unique and memorable Ebbets Field aroma.88 While there were multiple entrances to the ballpark, the famed rotunda stood out to many.89 The rotunda was also important for access to the ramps that gave fans their first view of the field. Former NYU President John Sexton believes the rotunda was “a critical threshold” that “connected the profane and ordinary with the sacred and the transcendent.”90 Even though it was a small ballpark, Doris Kearns Goodwin remembered the field as “the largest green space [I] had ever seen.”91 Testifying to the impact of televising every home game since 1947 was the experience of some young fans who were surprised that the field wasn’t the black and white they remembered from television.92 Television coverage was further enhanced in 1950 when O’Malley hired another legendary redheaded broadcaster, Vin Scully.93 Young fans also enjoyed Happy Felton’s Knothole Gang, where after a brief workout a Dodgers player chose a lucky Little Leaguer to come back and interview his favorite Dodger.94 Overall the atmosphere was reminiscent of a “carnival” or “a country fair.”95

Unfortunately, however there weren’t as many fans enjoying the experience in person. Although attendance exceeded 1 million in each of the final 12 seasons, it peaked at 1,807,000 in 1947 and ranged from 1 million to 1.3 million from 1950 on. Attendance was slightly over 1 million in the 1955 championship season and from 1953 to 1957 the team never led the league in attendance, although it won three pennants and a World Series.96 Vividly illustrating the new and disturbing reality was the failure to sell out Games Six and Seven of the 1952 World Series, especially 5,000 empty seats at Game Six.97 In retrospect, it seems the increased availability of games on television was the major cause of the decline in attendance, since the Dodgers broadcasts attracted twice as many viewers as the Giants and “half again as many as the Yankees.”98 Simply put, it was far easier for the average fan, deterred by the aging ballpark, very limited parking and the lack of “major arterial highways” to watch the game from his living room.99

All of this might have been tolerable had it been business as usual in the National League, but Boston’s 1953 move to Milwaukee turned one of the worst drawing franchises into one of the best. After attracting 1,826,000 fans their inaugural season in Wisconsin, the Braves topped the 2 million mark each of the next four seasons, close to doubling Brooklyn’s attendance.100 The declining attendance did not, however, impact the Dodgers’ bottom line. During the same five-year period (1952-56), the Dodgers made more money than any other team in baseball thanks to other sources of revenue.101

The Dodgers were obviously not in financial difficulty but the attendance issues were worrisome, a problem that beginning in 1950 was the responsibility of just one man, Walter O’Malley. Given the strong personalities involved, it’s no surprise that conflicts developed between O’Malley and Rickey in the late 1940s, especially over the rising expenses of the club’s extensive farm system and the new training facility at Vero Beach. Concern over these costs was magnified even more by “Rickey’s biggest management blunder,” the Brooklyn Dodgers football team, whose financial losses came close to “the team’s normal annual profit.”102 Rickey decided to leave Brooklyn in the summer of 1950 and with some skillful maneuvering drove the price of his shares to over $1 million. By early November O’Malley, along with John Smith’s widow, met the price and when Mrs. Smith dropped out shortly thereafter, Walter O’Malley, for better or for worse, was the majority owner of the Dodgers.103

Initially the shift of control benefited the fans at Ebbets Field. At the time baseball owners did little, if any, marketing, but O’Malley changed that, eliminating separate-admission doubleheaders, dramatically increasing community nights, expanding the Knothole Gang, and offering autograph days. At one point Newsweek magazine claimed the Brooklyn owner was “probably the most promotion-minded man in the game.”104 Although O’Malley had no complaints about the on-the-field product, the venue was another matter. Termed a “dirty, stinking old ballpark” by the club’s legendary radio and television voice Red Barber, Ebbets Field was clearly showing its age. Even more of a concern was the limited seating capacity and the even more limited parking.105 While the surrounding neighborhood remained middle or working class through the Dodgers’ departure, the migration of fans to the suburbs meant a more difficult trip to a ballpark where “rowdyism” was beginning to be considered all too common. At a time when family outings were becoming the norm, Ebbets Field didn’t seem to offer that kind of experience.106

It would have been irresponsible for any competent owner to avoid dealing with the future of Ebbets Field, and regardless of how one feels about Walter O’Malley, it’s hard to question his competence. Board meeting minutes from 1945 and 1946 confirm not just O’Malley’s concern about the issue, but his sense that the current site was not the solution.107 In 1953 the Brooklyn owner used the Eagle to inform the public that “Ebbets Field has never been considered” as the location for a new ballpark. Less publicly, O’Malley also began his vain effort to seek assistance from New York City government in the person of Robert Moses.108 The controversial story of the failed effort to build a new ballpark in Brooklyn and the team’s move to Los Angeles has been told many times and the debate will doubtless go on forever. It is beyond the scope of this essay, however, because even if the Dodgers remained in Brooklyn, they were going to leave Ebbets Field. The point of no return was reached on October 31, 1956, with the announcement that O’Malley had sold the ballpark to real estate developer Marvin Kratter for $3 million to be developed into apartments.109 Had the Dodgers stayed in Brooklyn, the 1960 demolition of the ballpark would have been delayed but not prevented.110

The question remains, however, whether renovating or rebuilding Ebbets Field was a practical alternative, especially since two contemporary ballparks, Fenway Park and Wrigley Field, continue to be two of baseball’s most popular venues. Certainly a lack of parking has not been a problem in Boston or Chicago. It has also been claimed that the small site (5.7 acres) made it impossible to expand the seating capacity but again the difference in Boston (6.3 acres) and Chicago (6.7) doesn’t seem to support so quick a decision that the solution wasn’t to be found on property O’Malley’s already controlled.111 Even if the neighborhoods surrounding Fenway Park and Wrigley Field were more stable, it can still be argued that the existing site didn’t get sufficient attention.112

In the end, it’s all speculation, and the Dodgers played their final game at Ebbets Field on September 24, 1957, before a crowd of 6,702. It is remarkable that over 60 years later so many people still have so many fond memories of the Brooklyn ballpark. The reason may be found in the title of Philip Lowry’s classic work about baseball stadiums: Green Cathedrals. The characterization resonates because it captures the sacred moments experienced by so many in those special places. In most cases, however, the old ballpark was either replaced with a new one or a team left town because it no longer had a critical mass of fans. At Ebbets Field, however, although ticket sales were down, attendance of over a million a year left many who never forgot their days and nights at the ballpark on Flatbush Avenue. The atmosphere at that final 1957 game has been described as wake-like, but it couldn’t have been a wake.113 A wake means someone died, and while the Brooklyn Dodgers and Ebbets Field are gone forever, they will never die.

SOURCES

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author accessed Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, and SABR.org.

NOTES

1 Bob McGee, The Greatest Ballpark Ever: Ebbets Field and the Story of the Brooklyn Dodgers (New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 2005), 11.

2 Brooklyn Standard Union, January 3, 1912: 11.

3 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, January 2, 1912: 22; Brooklyn Citizen, January 3, 1912: 5; Brooklyn Daily Times, January 3, 1912: 12.

4 Brooklyn Daily Times, January 3, 1912: 12.

5 Brooklyn Citizen, January 3, 1912: 5.

6 Ron Selter, Ballparks of the Deadball Era: A Comprehensive Study of Their Dimensions, Configurations and Effects on Batting, 1901-1919 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2008), 42; McGee, Greatest Ballpark, 39-40, 76, 108.

7 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, January 3, 1912: 22.

8 New York Tribune, January 3, 1912: 8; Brooklyn Daily Eagle, January 3, 1912: 22.

9 Selter, 42; Brooklyn Daily Eagle, January 3, 1912: 21-22.

10 Selter, 42; Brooklyn Daily Times, April 5, 1913: 17; McGee, 68.

11 Brooklyn Citizen, January 3, 1912: 5; Brooklyn Standard Union, January 5, 1912: 14; Brooklyn Daily Times, January 3, 1912: 12; January 5, 1912: 12.

12 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, January 3, 1912: 22.

13 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, January 4, 1912: 20; January 7, 1912: 62, Brooklyn Citizen, January 3, 1912: 5.

14 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, January 10, 1912: 23; February 10, 1912: 1; February 19, 1912: 19; March 5, 1912: 21.

15 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, March 20, 1912: 1; July 18, 1912: 17; August 15, 1912: 2; October 21, 1912: 20; Brooklyn Citizen, August 16, 1912: 1; Brooklyn Daily Times, September 21, 1912: 8.

16 John Zinn, Charles Ebbets: The Man Behind the Dodgers and Brooklyn’s Beloved Ballpark (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2019), 126-127, 131-132.

17 Zinn, Charles Ebbets, 134-135.

18 New York Times, April 6, 1913: 31.

19 Brooklyn Daily Times, April 5, 1913: 1.

20 Zinn, Charles Ebbets, 136-138.

21 Brooklyn Daily Times, April 5, 1913: 1; Brooklyn Daily Eagle, April 6, 1913: 1.

22 Zinn, Charles Ebbets, 138.

23 Philadelphia Inquirer, April 10, 1913: 10.

24 John Thorn, Pete Palmer, Michael Gershman, and David Pietrusza, Total Baseball: The Official Encyclopedia of Major League Baseball, Sixth Edition (New York: Total Sports, 1999), 106.

25 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 22, 1916: 22; Thorn, Total Baseball, 106.

26 Zinn, Charles Ebbets, 164; Brooklyn Daily Eagle, October 11: 1916, 24; October 12, 1916: 18.

27 Joseph Lannin to Ban Johnson, September 25, 1916, Box 89, Folder 10, August “Garry” Herrmann Papers, BA-MSS 12, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, Cooperstown, New York.

28 Thorn, 106.

29 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 14, 1918: 16.

30 New York Times, January 16, 1919: 10.

31 Zinn, Charles Ebbets, 82-84.

32 Zinn, Charles Ebbets, 174; Brooklyn Daily Eagle, July 6, 1917: 1; September 24, 1917: 1.

33 Zinn, Charles Ebbets, 176-178; Brooklyn Daily Eagle, May 5, 1919: 18.

34 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, February 11, 1920: 18; Thorn, 106.

35 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, August 31, 1920: 18.

36 Thorn, Total Baseball, 106.

37 John Zinn and Paul Zinn, Ebbets Field: Essays and Memories of Brooklyn’s Historic Ballpark, 1913-1960 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2013), 101-102, 106-107, 118-120.

38 Zinn and Zinn, Ebbets Field, 101, 108-109, 111, 113-117.

39 New York Times, May 20, 1925: 18.

40 Zinn, Charles Ebbets, 205-206.

41 Brooklyn Daily Times, May 6, 1925: 1; Andy McCue, Mover and Shaker: Walter O’Malley, The Dodgers and Baseball’s Westward Expansion (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2014), 30.

42 McCue, 30-31.

43 Organized Baseball, Hearings Before the Subcommittee of the Judiciary, House of Representatives, 82nd Congress, 1st Session, Serial, No. 1, Part 6, (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1952), 1600-1601.

44 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, February 14, 1928: 24.

45 Thorn, 106; Organized Baseball Hearings, 1600-1601.

46 Brooklyn Daily Times, January 8, 1931: 13.

47 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 1, 1930: 8.

48 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, February 5, 1930: 22.

49 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, February 14, 1928: 24; February 20, 1928: 22; May 15, 1930: 25.

50 Brooklyn Citizen, May 15, 1930: 8.

51 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, October 23, 1930: 26; December 22, 1930: 20; Philip J. Lowry, Green Cathedrals: The Ultimate Celebration of Major League and Negro League Ballparks (New York: Walker Publishing Co., 2006), 38-39.

52 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, December 22, 1930: 20; February 5, 1931: 24; February 13, 1931: 1.

53 Brooklyn Citizen, January 15, 1931: 6; Brooklyn Daily Times, February 13, 1931: 1.

54 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, February 17, 1931: 3; Brooklyn Daily Times, February 13, 1931: 1.

55 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, June 1, 1931: 20.

56 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, August 26, 1931: 20.

57 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, December 7, 1931: 26.

58 Thorn, 107.

59 Organized Baseball Hearings, 1600; McCue, 33.

60 McCue, 32.

61 McGee, 136.

62 McCue, 33, 35.

63 McGee, 136-137, 141.

64 McGee, 141.

65 Thorn, 107.

66 Peter Golenbock, Bums: An Oral History of the Brooklyn Dodgers (Chicago: Contemporary Books, 2000), 44.

67 McGee, 166.

68 Golenbock, 45-46.

69 McGee, 126-127, Zinn and Zinn, 69.

70 Zinn and Zinn, 191.

71 Zinn and Zinn, 77; McGee, 220-221.

72 McGee, 165.

73 McGee, 111-112; Zinn and Zinn, 147.

74 McGee, 164-165; Thorn, 107.

75 Zinn and Zinn, 71.

76 Drebinger quoted in McCue, 37; McGee, 168.

77 McCue, 42-43.

78 McGee, 174, 181; McCue, 45, 47-48.

79 New York Times, April 16, 1947: 32; Brooklyn Daily Eagle, April 16, 1947: 19; New York Daily News, April 16, 1947: 66-67; McGee, 196; Zinn and Zinn, 72.

80 Robert Caro, Lyndon Johnson: Master of the Senate (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2002), 694.

81 Zinn and Zinn, 83-88, 90, 94-99.

82 Zinn, Charles Ebbets, 130.

83 Zinn and Zinn, 141, 144-145,160, 166, 173.

84 Zinn and Zinn, 142, 151, 155, 160, 165, 167.

85 Zinn and Zinn, 140, 143, 148, 156, 158, 160.

86 McGee, 188-192, 194, 209-210, 233; McCue, 86-88.

87 Michael D’Antonio, Forever Blue: The True Story of Walter O’Malley, Baseball’s Most Controversial Owner, and the Dodgers of Brooklyn and Los Angeles (New York: Riverhead Books, 2009), 195.

88 Zinn and Zinn, 176, 189, 215-216.

89 Zinn and Zinn, 183, 189-190, 204.

90 Zinn and Zinn, 190, 199, 218.

91 Zinn and Zinn, 190.

92 Zinn and Zinn, 189, 212, 215; McCue, 55.

93 D’Antonio, 118-119.

94 Zinn and Zinn, 191, 201.

95 Zinn and Zinn, 178, 209.

96 Thorn, 107.

97 McCue, 121; D’Antonio, 163.

98 McCue, 124.

99 McCue, 124-125.

100 Thorn, 107.

101 D’Antonio, 164.

102 McCue, 69-73.

103 McCue, 77-81.

104 McCue, 84, 86, 91, 114-115.

105 McCue, 56, 121, 124.

106 McGee, 163, 240, 276-277; D’Antonio, 110-111, 218.

107 McCue, 56-57.

108 McCue, 129; Brooklyn Daily Eagle, December 11, 1953: 18.

109 McGee, 263.

110 McGee, 13, 15.

111 D’Antonio, 91; Selter, 32, 44, 67.

112 McCue, 123.

113 Zinn and Zinn, 212.