Ridgewood Park (New York)

This article was written by Bill Lamb

For three consecutive seasons in the late 1880s, the Brooklyn Grays/Bridegrooms of the major league American Association relocated their home games from their grounds at Washington Park to a newly opened venue: Ridgewood Park II, originally known as Wallace’s Ridgewood Park or Grounds. The reason was straightforward: Ridgewood was located in Queens, where state blue laws prohibiting the playing of professional baseball and other amusements on Sunday were loosely enforced, if at all.1 In 1890, Ridgewood Park II served as the everyday home ballpark of a hastily organized AA replacement club, the Brooklyn Gladiators. All the while and for almost three decades thereafter, Ridgewood also hosted amateur, semipro, and pre-Negro Leagues baseball contests, as well as soccer, hurling, and American and Gaelic football matches. Vestiges of the ballpark endured until obliterated by neighborhood industrialization in 1959. The story of this now-forgotten multi-sport facility follows.

New York Sunday Blue Laws and Major League Baseball’s Initial Foray into Queens

In the eastern parts of this country, the Puritan tradition of restraint upon commerce and amusement on the Sabbath dates back to the mid-17th century. In New York, Sunday blue laws were adopted by the Dutch inhabitants of New Amsterdam in 1656 and maintained thereafter by British colonial authorities.2 Among other things, the law prohibited traveling, working, shooting, fishing, sporting, playing, hunting, horse racing, or tavern visits on the Lord’s Day. Despite their unpopularity with the Irish and German immigrants arriving in New York throughout the latter part of the 19th century, Sunday blue laws remained sacrosanct to a New York state legislature dominated by nativist upstate Protestants. But by the 1880s, enforcement of Sabbath restrictions was spotty, particularly in the greater New York City area.

In Gotham itself, then consisting of only Manhattan and parts of the West Bronx, pro-blue law forces were potent enough to prevent the playing of professional baseball on Sunday. The same held true in Brooklyn, then an independent municipality and the nation’s fourth largest city.3 With the Sabbath being the only day available for pursuit of leisure activity by the middle and working classes, New York and Brooklyn clubs in the National League and American Association were therefore precluded from opening their ballparks on the day most likely to attract a large number of fans. But the situation in Queens was different.

Less densely populated with considerable open space, Queens was a popular Sunday destination for city dwellers from New York and Brooklyn. Delivered by horse-drawn carriage and rail, visitors enjoyed hotels, picnic grounds, and parklands open to the public. The revenue generated by the tourist trade and the development which it spurred were welcomed by local officials who overlooked infringement of Sabbath blue laws. And soon, Sunday diversions expanded to include baseball.

In early 1885, local brewery owner George Grauer purchased 10 acres of greensward adjoining his already popular picnic grove in Ridgewood, an ethnically German enclave situated in Queens, along the border with Brooklyn. There, he laid out an enclosed baseball diamond in hopes of attracting paying customers to games staged by the Long Island Athletic Club and other area amateur teams.4 These grounds were known as Grauer’s Ridgewood Park, distinguished from our subject by designating it as Ridgewood Park I. During 1885, the Ridgewood Base Ball Club, the crème of amateur Queens nines, played a busy schedule of games and went 59-20, with only four of their losses being inflicted by other non-professional clubs.5

On April 11, 1886, the Brooklyn Grays of the American Association trounced the Ridgewoods, 22-1, in a Sunday exhibition game played at Ridgewood Park I. Among those impressed by the 3,000 spectators who paid their way into the ballpark to observe the non-contest was Brooklyn club owner-field manager Charles Byrne. Equally noteworthy to Byrne was the fact that the game went unmolested by local police, a lack of enforcement of Sunday blue laws that sportswriter Ren Mulford, Jr. later attributed to generous amounts of “pin money” bestowed on “a small army” of Queens officials.6 Recognizing the situation’s income potential, the Brooklyn club boss promptly arranged the rescheduling of American Association games for the Grays on Sundays at Ridgewood Park.

On May 2, 1886, the Brooklyn Grays and the AA rival Philadelphia Athletics inaugurated Sunday major league baseball in New York with a poorly-played “muffin game” that ended in a 19-19 tie after eight innings.7 The sporting press was less than enthralled with the venue, deeming the playing grounds “too small,” and complaining that “ball after ball was knocked over the fence and lost.”8 But at the turnstiles, the game proved a resounding success, with about 7,500 fans in attendance. Queens police were nowhere to be seen.

Thereafter, the Grays played 13 more Sunday afternoon games at Ridgewood Park I, winning eight.9 Those contests were almost invariably well-attended, a major factor in the 100,000-patron surge in Brooklyn home game attendance over the previous season.10 But as the summer wore on, both Ridgewood Park proprietor Grauer and Brooklyn club owner Byrne grew dissatisfied with their arrangement. For his part, Grauer came to believe that he could simply make more money if he abandoned Sunday baseball and used the Ridgewood Park property to expand his lucrative picnic grove operation. Byrne had various reasons for his attitude. The “much maligned playing grounds at Ridgewood”11 were poorly manicured and maintained. The space at Ridgewood Park was also confined, the principal problem being outfield fences that were insufficiently distant, resulting in catchable fly balls turning into ground-rule doubles. More important, the per diem charged by Grauer for use of the ballpark, perhaps $200 per Sunday, was deemed exorbitant by Byrne, seriously cutting into the profits generated by games at Ridgewood.12 Happily for Charlie, an alternative to Grauer’s Ridgewood Park was located only two blocks away.

Ridgewood Park II

Ridgewood Park II was the brainchild of William Willock Wallace, the enterprising secretary of the Ridgewood Athletic Association. Born in Brooklyn in 1856 to Scotch-Irish immigrants, young Wallace worked as a compositor setting type for the New York Press. He was also an ardent baseball enthusiast. In September 1884, Wallace arranged for the association to rent property in Ridgewood about two blocks south of Grauer’s picnic grove. A section of the rental grounds measuring 750 by 400 feet was then transformed into an athletic field featuring a baseball diamond.

On April 5, 1885, the association’s amateur nine hosted the independent Atlantic Club of Brooklyn on their new field, dropping a 3-1 decision before 3,000 onlookers. A contingent of local police was also on hand but did not interfere with the action, finding “no disturbance of the Sabbath repose of the community.”13 After a profitable summer — revenue from the first year of operation was later estimated at an extraordinary $25,00014 — Wallace decided to expand the venture, forming the Ridgewood Exhibition Company. Joining him in the new stock company were fellow cranks William A. Mayer, Harry Rueger, and J.F. O’Keefe. Thereafter, the REC purchased the rented athletic field property for some $12,000 and set about enhancing the seating capacity of the grounds.15 In due course, Sunday baseball gained a second venue in conveniently situated Ridgewood: Wallace’s Ridgewood Park aka Ridgewood Park II.

The schedule at the new ball field included a regular regimen of Sunday games. In addition to the amateur Ridgewoods, the Wallace grounds were utilized by the Jersey City Jerseys of the minor Eastern League.16 Given that Jersey City did not have blue laws prohibiting Sabbath baseball at their home field, the Jerseys’ willingness to trek to Queens represented a powerful testament to the drawing power of Sunday baseball in Ridgewood. The EL’s Bridgeport (Connecticut) Giants also played occasional Sunday exhibition games at Ridgewood Park II during the 1886 season.17

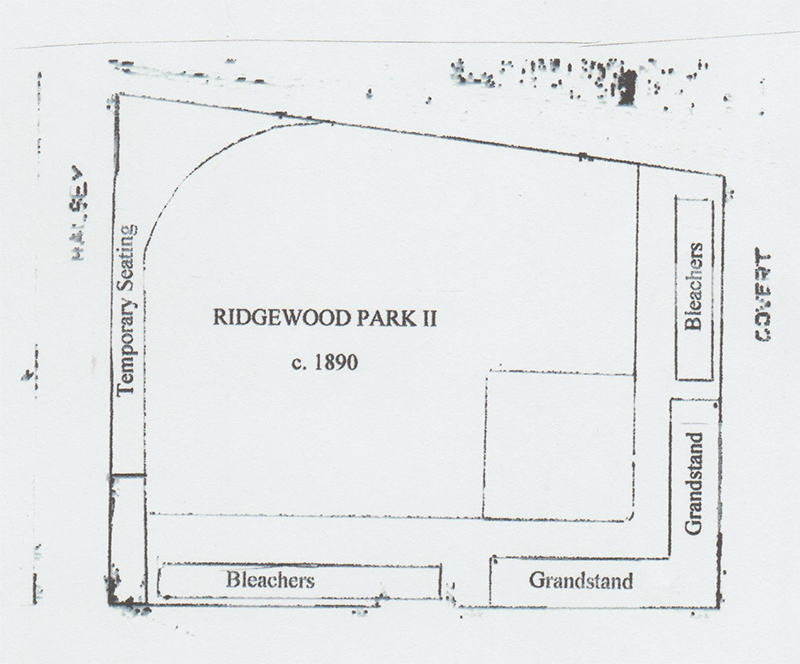

In late March 1887, the New York Herald reported that “Wallace’s park will hereafter be known as Ridgewood Park,” and was designated this season’s Sunday home grounds of the Brooklyn Grays.18 To accommodate the arrival of a major league club, William Wallace and company installed a roofed grandstand behind home plate capable of seating 2,000 spectators. In addition, open bleacher sections were extended along both third and first base lines.19 When completed, the ballpark’s seating capacity “will be sufficient to comfortably accommodate from 12,000 to 15,000 spectators.”20 Or so it was claimed. In the interim, the 1887 season began.

On April 10, the Brooklyn Grays assayed their new Sunday grounds, hammering the Boston Blues of the minor New England League (and also the reserve nine of the National League Boston Beaneaters), 21-4, in a preseason exhibition contest played before a crowd estimated at 8,000.21 Two weeks later, major league baseball at Ridgewood Park II began in earnest. On April 24, Brooklyn and the Baltimore Orioles inaugurated Sunday major league baseball at the Ridgewood ballpark. The grounds were overwhelmed by the “largest crowd of spectators ever to witness a match outside of Brooklyn,” with nearly 10,000 reportedly in attendance.22 Every available seat was taken, with thousands more onlookers ringing the outfield fences. The throng, alas, went home unhappy as Baltimore rallied late to capture a 12-8 verdict. Following a six-week hiatus in the action, some 7,300 fans witnessed the Grays notch their first victory at their Sunday ballpark, edging Cleveland, 10-9, on June 5.23 From there on, Brooklyn alternated victories and defeats, finishing the season with a 6-9 (.400) record at Ridgewood Park II, somewhat worse than the club’s 60-74 (.448) mark, overall.

Whatever the ballpark winning percentage, games in Ridgewood had been an unqualified success at the gate. Taking Sunday game attendance estimates published in Brooklyn newspapers at face value, the Grays drew some 107,300 fans to 15 games played in Ridgewood Park II,24 yielding an average crowd of 7,153. This was approximately two and one-half times the attendance of home games held at Washington Park (165,700 fans divided by 58 home dates equals a 2,857 per game attendance average).25 Wallace and company then spent the off-season expanding the ballpark’s seating capacity. The grandstand was enlarged and extended farther down the third base line. Temporary seating that could be removed for fall events like soccer, hurling, and football was installed along the left and center field fence line. This brought the seating capacity of Ridgewood Park II for baseball to approximately 10,000.26 With standing room, even more could be accommodated.

For the 1888 season, the Brooklyn club, now called the Bridegrooms,27 obtained no fewer than 20 Sunday home game dates. And when Brooklyn was on the road, either the Newark Trunkmakers or the Jersey City Skeeters of the minor Central League would be Ridgewood Park II’s Sunday tenants.28 But by now storm clouds were gathering on the political front. The Sunday Observance Association of Kings County and prominent Brooklyn clergymen began raising public objection to the disregard of Sunday blue laws in Queens. In late June, club owner Byrne attempted to evade a possible blue laws citation by admitting Sunday game patrons free, requiring instead the purchase of a scorecard.29 But this dodge did not reproduce the revenue of paid admissions, particularly that generated by the sale of pricier grandstand seats, and was promptly abandoned.30 Happily for Byrne and the REC, Queens officials continued to ignore Sunday baseball — at least for the time being.

Under new manager Bill McGunnigle, Brooklyn (88-52, .629) rose dramatically in AA standings, finishing second to the St. Louis Browns. But the club slumped at the gate, drawing a combined 245,000 (28,000 fewer) patrons to its two ballparks in 1888. Nevertheless, Byrne renewed his arrangement for Sunday use of Ridgewood Park II for the coming season. Soon thereafter, however, problems surfaced between Byrne and REC honcho Wallace. In February 1889, a dispute between the two men regarding the distribution of revenue from the previous season became public.31 Unless resolved to his satisfaction, Wallace threatened to subdivide Ridgewood Park II into building lots and sell them off at five times ($500 per lot) what they had cost the REC four years earlier. “By next July, the elevated railroad will be in running order to within a short distance of our grounds,” said Wallace. Given the increased tourist trade likely to be attracted to the area, “we really do not care whether the Brooklyn club plays here again or not.”32 In time, the problem (which may have involved a difference over no more than $100) was worked out. But the incident contributed to club owner Byrne’s growing dissatisfaction with his club’s affiliation with the American Association. For now, however, the status quo prevailed, with the Newark Little Giants of the newly formed Atlantic Association taking the Sunday playing dates not allotted to Brooklyn.33

With Brooklyn headed for an American Association pennant, overflow Sunday crowds returned to Ridgewood Park II. On May 5, 1889, “the largest assemblage that ever witnessed a game at Ridgewood Park”34 arrived to witness the Grooms play Philadelphia. In the sixth inning, spectators who had crowded behind the flimsy center field fence swarmed upon the grounds in such numbers that the game became unplayable and had to be called a 1-1 tie.35 On hostile editorial pages, the incident was blamed on official tolerance of Sunday baseball and generated renewed calls for enforcement of blue laws by authorities in Queens.36 The unruly crowd behavior also catapulted Brooklyn bluenoses into action, with the Kings County Sunday Observance Association taking the lead.37 Adding his voice to the complaints was the Right Reverend Abram Newkirk Littlejohn, Episcopal Bishop of Long Island.38 Still, the Sunday games continued with an overflow crowd estimated at 16,000 in attendance for a September game against St. Louis. But a reckoning was on the near horizon.

In early October, a Queens County grand jury was empaneled to investigate alleged Sunday blue law violations at Ridgewood Park II. In time, misdemeanor charges were returned against William Wallace and the other principals of the Ridgewood Exhibition Company (but not against Brooklyn club boss Byrne or the ball club itself).39 While the charges awaited disposition, Queens officials, whether coincidentally or not, found the time propitious for completion of the neighborhood traffic grid by running a portion of Halsey Street that was previously “paper-only”40 through the Ridgewood Park II outfield. Curiously, however, officials chose not to obliterate the grounds as a ballpark site entirely by declining to complete a second “paper street” (a section of Eldert Street) through the infield.41

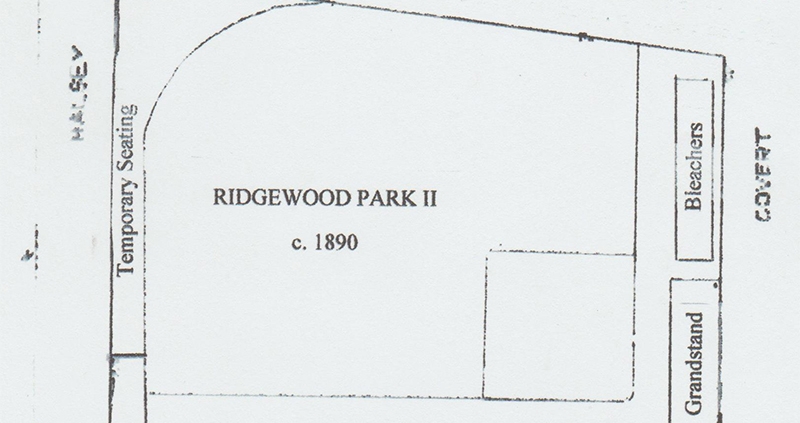

Undaunted, Wallace and company responded by modifying the grounds so that baseball playing could continue there. To adjust for the Halsey Street truncation of left field, home plate was moved back 75 feet and a new grandstand seating 3,500 constructed behind it.42 A picket fence was then installed to define the new outfield territory. Regrettably, the precise dimensions of Ridgewood Park II have not been discovered. But tellingly (and much unlike Grauer’s Ridgewood Park), no criticism of the ground’s playing space has been found in game reportage. The conclusion: the dimensions of Ridgewood Park II were unremarkable for a late 1880s ballpark.

As the year 1889 drew to a close, Sunday baseball at Ridgewood Park II was only a sideshow to a far larger drama involving the very structure of major league baseball. A new, talent-rich organization had just been formed for the 1890 season: the Players League. While National League clubs and, to a lesser extent, American Association members tried to fend off PL raids on their player rosters, Brooklyn club boss Byrne took a drastic step. He removed his American Association pennant-winning team from the AA and affiliated it with the National League. Meanwhile, the Players League also installed a strong nine in the City of Churches, one led by erstwhile New York Giants star John Montgomery Ward, the founding genius of the PL. Neither the NL Brooklyn Bridegrooms nor the PL Brooklyn Ward’s Wonders, however, intended to play any games in Queens.

Enter Jim Kennedy, a 27-year-old New York sportswriter and would-be baseball mogul, with a proposal to organize a third major league club for Brooklyn. Kennedy’s club, soon dubbed the Brooklyn Gladiators, were to fill the void left in American Association ranks by the departure of Byrne.43 An immediate problem confronting the fledgling operation was finding playing grounds. With the National League occupying Washington Park and the Players League ensconced in newly erected Eastern Park, there were no suitable grounds left in Brooklyn for the Gladiators. Kennedy’s club, therefore, scheduled its home games for the nearest available ballpark in neighboring Queens — Ridgewood Park II.

The collaboration of club and ballpark proved an unsatisfactory one. The structural modifications to Ridgewood Park II left critics unsatisfied, Brooklyn sportswriter J. F. Donnelly lamenting a “wild, backwoods air that pervades the grounds and everything is distressingly crude.”44 Worse yet was the product in uniform, a hapless collection of has-beens and nonentities unlikely to attract much fan allegiance. With a modest home crowd of 2,000 in attendance, the Gladiators dropped their major league debut to the Syracuse Stars, 3-2. The following day, Brooklyn entered the win column with an unsightly 22-21 victory over Syracuse before only 700 spectators.

On June 8, 1890, Brooklyn bested Syracuse, 9-5. It was the final major league game played at Ridgewood Park II. The following day, Kennedy transferred Gladiators home games to the Polo Grounds in north Manhattan, where they defeated Syracuse again, 13-7.45 With Brooklyn in last place and teetering on the brink of bankruptcy, AA officials then put the Gladiators on the road for the next 34 games. These events prompted a chagrinned William Wallace to terminate Kennedy’s lease on Ridgewood Park. But Wallace and company soon had more serious concerns than contract non-performance by their ballpark tenant. In July, a Queens jury convicted Wallace and REC cohorts Mayer and Rueger of maintaining a nuisance in allowing Sunday baseball at the Ridgewood grounds.46 The penalty imposed was a $500 fine, with jail time promised the defendants should there be a second offense. In the meantime, the American Association pulled the plug on the Brooklyn Gladiators, transferring the franchise to Baltimore in late August.

Ridgewood Park II: The Ensuing Decades

It would be 74 years before another major league game was played in Queens. But Ridgewood Park II did not sit idle during that time span. A full slate of fall sports — soccer, hurling, American and Gaelic football — placed spectators in the stands throughout the 1890s. As for baseball, local officials tolerated Sunday games between non-professional nines at Ridgewood Park. A blind eye was even turned toward a Sabbath exhibition game between the amateur Ridgewoods and Cincinnati’s American Association club in July 1891. But ballpark proprietor Wallace was unwilling to jeopardize his liberty for a Sunday regular season game between AA clubs, turning down St. Louis Browns owner Chris Von Der Ahe’s proposal to match his club against the Philadelphia Athletics at Ridgewood Park II.47

Beginning in the late 1890s, pre-Negro League clubs like the Genuine Cuban Giants began playing an occasional Sunday game at Ridgewood Park.48 This and like activity spurred Wallace to renovate the grounds, a process that continued sporadically until the advent of American entry into World War I in April 1917. Prospects for major league baseball’s return, however, were dashed in 1904 when the New York Highlanders were thwarted in an effort to play Sunday games at Ridgewood Park II.49 Still, semipro and amateur games continued, and the pre-Negro Leagues New York Royal Giants became ballpark tenants in 1912.50

On September 19, 1917, the grandstand and a large portion of the bleachers at Ridgewood Park II were consumed by a fire of unknown origin. Thereafter, Wallace erected a smaller version of the ballpark on the northern part of the site. Ten years later, William Wallace died at age 71. In 1928, the grounds were reduced in size by industrial development, with the remainder, useful for soccer and the odd track and field meet (if not for baseball), taking the name Grand Stadium. This, too, eventually fell victim to urban sprawl. In 1959, the last remnants of Ridgewood Park II were swallowed by buildings construction. As with many other vanished ballparks, no memorial to the grounds can be found the on the site today.

Acknowledgments

This article was originally published in the December 2020 issue of Palaces of the Fans, the bi-annual newsletter of SABR’s Ballparks Research Committee.

This version was reviewed by Rory Costello and Norman Macht and fact-checked by Don Zminda,

Sources

The sources for the information provided herein are identified in the endnotes.

Notes

1 Queens County abuts Brooklyn to the east.

2 See Sam Roberts, “Alcohol, Guns and Golf: The Long History of Blue Laws in New York,” New York Times, June 16, 2016: A21. The term blue law is thought to be derived from the Puritan practice of binding their religious laws in blue-covered books.

3 The modern five-borough (Manhattan, Brooklyn, Bronx, Queens, and Staten Island) New York City did not come into existence until January 1, 1898.

4 Per Andrew Ross and David Dyte, “The Parks of Ridgewood,” viewable online at BrooklynBallParks.com.

5 See “Notes and Comments,” Sporting Life, December 16, 1885: 3. The other 16 Ridgewood defeats came at the hands of major and minor league clubs.

6 Ren Mulford, Jr., “Cincinnati Chips,” Sporting Life, December 4, 1889: 2. Whether Queens officials were paid off by ballpark proprietors or ball club owners or both, is uncertain.

7 The description applied to the contest in “Sunday Games,” Baltimore Sun, May 3, 1886: 6.

8 Per “Uninteresting Baseball,” New York Tribune, May 3, 1886: 2.

9 According to Retrosheet.

10 In 1885, Brooklyn had drawn 85,000 fans to games at Washington Park. In 1886, the Grays drew 185,000 patrons to games held between its everyday home field in Brooklyn and its Sunday grounds at Ridgewood Park, per Robert L. Tiemann, “Major League Attendance,” Total Baseball (Kingston, New York: Total Sports Publishing, 7th ed., 2001), 74.

11 The description of Brooklyn correspondent Fulton in Sporting Life, June 16, 1886: 1.

12 Ross and Dyte, “Grauer’s Ridgewood Park,” in “The Parks of Ridgewood,” above, 1.

13 Ross and Dyte, “Wallace’s Ridgewood Grounds,” in “The Parks of Ridgewood,” above, 2. See also, “News and Comments,” Sporting Life, April 15, 1885: 7.

14 See “New York News,” Sporting Life, May 29, 1889: 5.

15 “New York News,” above.

16 As reported in Sporting Life, July 3, 1886: 6, and elsewhere.

17 See “On the Diamond,” New York Herald, June 5, 1886: 7.

18 “Baseball Notes,” New York Herald, March 29, 1887: 8. Grauer’s Ridgewood Park, meanwhile, had been converted entirely to picnic use.

19 Ross and Dyte, above, 2-3.

20 Per Early Spring Sports,” New York Herald, March 14, 1887: 6. See also, “Base Ball Notes,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, March 22, 1887: 5.

21 In “A Waterloo for Boston,” Brooklyn Union, April 11, 1887: 3. An out-of-town newspaper report put the crowd in the 6,000-7,000 range. See “Base Ball at Brooklyn on Sunday,” Boston Journal, April 11, 1887: 3.

22 “A Fatal Inning,” Brooklyn Eagle, April 25, 1887: 1. Retrosheet places the game’s attendance at 8,000.

23 “Weak Batting,” Brooklyn Eagle, June 6, 1887: 1. The Brooklyn Times placed the crowd at “about 7,000.”

24 Sunday game attendance estimates were a regular feature of the reportage of the Brooklyn Eagle, Brooklyn Times, and Brooklyn Citizen.

25 The lowest published attendance figure for an 1887 Brooklyn Sunday game was 4,000, a 4-3 loss to St. Louis incurred under threatening skies on July 24. A crowd of 10,000 (or 8,000 according to the New York Times) saw the best-played contest in Ridgewood that season, a 2-0 New York Mets win over the home side on August 14.

26 Ross and Dyte, 4.

27 For more on 19th century team nicknames, see Ed Coen, “Setting the Record Straight on Major League Team Nicknames,” Baseball Research Journal, Vol. 48, No. 2, Fall 2019, 67-75.

28 Per Sporting Life, April 4, 1888: 2.

29 As noted in the New York Tribune, June 11, 1888: 8.

30 Like other American Association clubs, Brooklyn charged the standard 25 cents for general admission. But grandstand seats went for double that. The April 29 game against Philadelphia, for example, drew a reported crowd of 5,481, “and of these over twelve hundred paid 25 cents extra for seats in the grandstand.” “A Close Game,” Brooklyn Eagle, April 30, 1888: 1.

31 As reported in “Brooklyn’s Sunday Games,” New York Herald, February 15, 1889: 8; “Demolition of the Polo Grounds,” New York Tribune, February 15, 1889: 2; “The Sporting World,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, February 17, 1889: 2; and elsewhere.

32 “They Are Not Afraid,” Brooklyn Citizen, February 15, 1889.

33 Per “World of Sports,” Waterbury (Connecticut) Evening Democrat, May 28, 1889: 5. The Sunday ballpark rental fee charged Newark was $200 per game.

34 “Exciting Base Ball Game,” Helena (Montana) Weekly Herald, May 9, 1889: 3. The New York Tribune placed the game attendance at 12,614.

35 Under the rules, Brooklyn’s failure to maintain security on its grounds should have resulted in the game being forfeited to Philadelphia, 9-0. But it was not.

36 See e.g., New York Tribune, May 6, 1889: 6: “This occurrence should give a decided setback to Sunday ball-playing, which is only popular with certain classes of men and tends inevitably to bring a fine and noble game into disrepute.” A next-day Brooklyn Union editorial, meanwhile, opined that “the only sure way to prevent repetition [of the disgraceful exhibition] is by stopping professional ball playing on Sunday.”

37 See “Long Island News,” Brooklyn Times, June 10, 1889: 5.

38 A letter to the editor critical of non-enforcement of blue law restrictions upon Sunday baseball from Bishop Littlejohn was published in “Our Sunday,” Brooklyn Times, August 3, 1889: 1.

39 See “Sunday Ball Playing,” Brooklyn Times, October 22, 1889: 1.

40 A “paper street” is one that appears on city planning maps but that has not been constructed in fact.

41 Eldert Street lies between Covert and Halsey Streets on the ballpark diagram, above. More than 130 years later, the paper section of Eldert Street remains unconstructed.

42 Ross and Dyte, 4.

43 For more on the formation of the Brooklyn Gladiators, see the BioProject profile of club founder Jim Kennedy.

44 “All Dwelt in Harmony,” Sporting Life, May 17, 1890: 12.

45 See “Manager Kennedy Changes Dates,” New York Herald, June 13, 1890: 8. See also, “Condensed Dispatches,” Sporting Life, June 14, 1890: 1.

46 See “Condensed Dispatches,” Sporting Life, July 26, 1890: 1.

47 As reported in “Von der Ahe Brooklyn Raid,” Sporting Life, May 23, 1891: 5.

48 See “Baseball Notes,” New York Sun, October 16, 1897: 4.

49 See Ross and Dyte, 6. The Highlanders, however, were able to play some Sunday exhibition games against the Ridgewoods at Ridgewood Park II. Legislation to permit Sunday baseball in New York was not enacted until April 1919.

50 Ross and Dyte, 7-9.