Terrapin Park / Oriole Park (Baltimore, MD)

This article was written by David Stinson

“Terrapin Park, Federal League, Baltimore Md,” postcard published by The Chessler Company. (Courtesy of David B. Stinson.)

Terrapin Park, also known as Oriole Park (V), was the home of the Federal League Baltimore Terrapins in 1914 and 1915, the International League Orioles from 1916 to 1944, and parttime home field to the Negro National League Baltimore Elite Giants from 1939 to 1942.1 It was located at the northwest corner of what is now Greenmount Avenue (formerly York Road) and 29th Street, across the street from the site of Oriole Park (II) and (IV).2 First base paralleled East 29th Street, right field paralleled Greenmount Avenue, left field paralleled East 30th Street, and third base paralleled Vineyard Lane.3

Ned Hanlon, the manager of the National League Orioles from 1892 to 1898, played an important role in bringing major-league baseball back to Baltimore in 1914. After the 1899 season, Baltimore lost its National League franchise when the league contracted from 12 teams to eight. An inaugural member of the American League in 1901, the Orioles played only two seasons in Baltimore. In December 1902, after the demise of the American League Orioles,4 Hanlon purchased American League Park for $3,000.5 In 1903 Hanlon acquired an Eastern League franchise from Montreal and moved it to Baltimore.6 Hanlon renamed the team the Orioles and the team moved into the former American League Park, rebranded as Oriole Park,7 installing former National League Oriole Wilbert Robinson as manager of the team.8

While owner of Baltimore’s Eastern League Orioles, Hanlon was also manager of the National League Brooklyn Superbas from 1899 to 1905, and the National League Cincinnati Reds in 1906 and 1907.9 His hopes of bringing a major-league team back to Baltimore at the former American League Park never materialized and, after the 1909 season, Hanlon sold the team, and the ballpark, to Jack Dunn, a former American League and Eastern League Oriole, as well as one of Hanlon’s Brooklyn Superbas’ star pitchers.10

In 1913 the Federal League was formed as an independent league with six teams located in the Midwest.11 In October 1913 Baltimore was offered a franchise in the Federal League for the 1914 season.12 As observed by the Baltimore Sun:

This is considered the time to step into a new major league that has a chance to become as good as any. If Baltimore lets the chance slip, it may have to resign itself to being a minor league town for the balance of its day.13

On October 27, 1913, Baltimore filed its Federal League Articles of Incorporation, which called for issuance of both preferred and common stock.14 As for the location of the team’s ballpark, the Sun reported the likelihood of building on a tract of land owned by Hanlon just across the street from Oriole Park (IV):

Those interested in the club have an option on a fine tract for a ball park, lying just northwest of the present Oriole Park, although it has not definitely been selected. The ground belongs to Edward Hanlon, former manager of the champion Orioles.

The proposed ground is that upon which was situated the old Brady mansion for a time used as a school-house. It is said that not a great amount of grading will be necessary as the elevation is such that the bleachers could be built upon it without much excavation.

The ground is 90 feet west of York road and on the east extends from Twenty-ninth to Thirtieth street, a distance of about 400 feet. The land runs westward to Gilmer Lane, a distance of about 600 feet. Gilmer lane runs at an angle of about 45º, making the plot irregular.

If the ground is selected, there will be a triangle used for automobiles. It is said that the grandstand may be placed along Gilmer lane and Twenty-ninth street and that the sun would thus never strike the patrons. The bleachers could be arranged so that the sun would strike them from the side.

Mr. Hanlon’s counsel has just completed arrangements for the purchase of a small piece of land at Gilmer lane and Twenty-ninth street, which thus gives Mr. Hanlon a field considered very desirable.

Wherever the park is located, the plans are to build a better stand than Baltimore has ever had and to have a seating capacity on all stands of at least 15,000.15

Baltimore officially was admitted to the Federal League on November 1, 1913.16 The team reviewed plans for the ballpark on November 7, 1913.17 As reported in the Baltimore Sun:

According to the plan as presented, the grandstand would be built near the southwest corner of the lot, curving behind the home plate. At either end pavilions are proposed and in right field a bleacher stand. If the grandstand is built with an upper deck, a total seating capacity will be about 10,000. If a single decker is built, the seats will be 3,000 to 4,000 fewer.

Behind the grandstand is a space that it is proposed to make a parked place for automobiles.18

On November 12, 1913, Hanlon was elected a director of the Baltimore Federal League club and reportedly purchased “a considerable amount of the stock.”19 Hanlon told the Baltimore Sun:

“This is not the first time that I have tried to bring big league ball back to this city and I know something of the difficulties. If we make no effort to break the present monopoly in organized baseball, Baltimore seems permanently side-tracked in a league from which no matter how many stars we might develop they would promptly be taken away to strengthen teams in cities perhaps smaller than Baltimore.”20

As a director of the Baltimore franchise, Hanlon insisted that the team sell $10 shares of the corporation to encourage fan participation in the club itself, giving each stock owner full voting power and a first lien on the club’s property, plus 7 percent dividends.21 At the end of December 1913, the team selected Hanlon’s tract of land and Hanlon completed his purchase of additional land necessary to construct the new Baltimore Federal League ballpark:

The Feds have selected the lot just in the rear of Oriole Park, which is owned by Ned Hanlon. It was not until yesterday that the deal was put through for a small tract which was necessary to make a suitable ball ground.

Hanlon yesterday purchased from James Keelty and his wife a tract beginning at the southeast corner of Gilmer lane and Thirtieth street measuring 73.8 by 293 feet. The sale was made in fee simple and the title was examined by the Title Guarantee and Trust Company.

With all the necessary ground in their possession – for the directors of the local club have decided upon Hanlon’s lot as the home of their team – it is probable that the work of grading and building the stands will begin in a very short time. The directors are not at all worried about having the grounds in tiptop shape for the opening of the championship season, for Hanlon has called their attention to the very short time required to transform old Union Park from a lot into a ball yard.22

The ballclub petitioned the First Branch City Council for an ordinance approving its plans for the ballpark at York Road on January 12, 1914.23 The plans submitted by the team called for “a large wooden structure on steel supports in the triangle formed by the York road, Twenty-ninth street, Thirtieth street and Gilmer lane.”24 The ordnance specified additional details about the ballpark:

The ordinance authorizes the club to build a grandstand 110 feet long, 65 feet high and 69 feet wide within the triangle. It is to extend east on Twenty-ninth street, a distance of 182 feet and 08 inches, and northeast on Gilmer lane 182 feet. There is to be a single deck stand on Twenty-ninth street, starting 20 feet east of the grandstand and extending parallel with Twenty-ninth street for a distance of 180 feet, and to be 85 feet high and 52 feet wide.

Provision is also made for a single deck stand on Gilmer lane, 84 feet northeast of the grandstand, and to be 115 feet long, 38 feet high and 59 feet wide.

The bleachers are to be on the York road, according to the plan filed with Building Inspector Stubbs by Architect Simonson, and they will be 145 feet long and 190 feet wide. There is to be another wooden stand for bleachers on Thirtieth Street.25

Construction of the new ballpark began on January 20, 1914, with a groundbreaking ceremony, featuring Baltimore Mayor James H. Preston and directors of the club.26 Architect Otto G. Simonson submitted his plans and specifications for the ballpark on January 26, 1914, and bids for construction of the ballpark grandstand, two covered pavilions, and bleachers were set to be opened on January 31, 1914.27 The architect’s plans for the ballpark were as follows:

In round figures the seating capacity will be about 13,000 persons, divided thus: Grandstand, 7,000: pavilion A, 2,509; pavilion B, 1,400, and the bleachers, 2,100. Pavilions A and B will be covered. Directly in the rear of the grandstand will be parking space for motor and other vehicles.

The distance from home plate to the left-field fence is about 300 feet, to the right field fence about 335 feet and to the intersection of centre and left-field fences about 460 feet. Between home plate and the grandstand will be a distance of 76 feet.28

Joe Smith was named groundskeeper for the new ballpark, and in March 1914 he installed beneath the diamond “a network of passages in which will be put the tile for draining purposes.”29 The new team was named the Terrapins and its new home was named Terrapin Federal League Ball Park.30 The team’s uniform included a Terrapin emblem on the front of the shirt.31 According to the Baltimore Sun, “[T]he words ‘Terrapin Park’ will be placed in large letters over the main entrance to the park and also above the other egresses.”32

Construction of Terrapin Park neared completion by the end of March. A 12-foot fence was erected “from the right-field bleachers to the extreme point in centre field, and thence to the left field pavilion.”33 The dressing rooms and showers for the Terrapins, the visiting clubs, the club secretary, and the umpires were located beneath the right section of the grandstand, “only a few steps” from the field.34 Five flagpoles were installed inside the park, with the largest placed in center field.35

Although the ballpark was built mainly of wood, the Baltimore Sun remarked, “[I]f patrons of the game will help keep big league ball here the concrete stand will replace the wooden ones and the park will be as imposing as any in the country.”36 The grandstand and the press gates were located at the intersection of Barclay and Twenty-ninth streets.37 A press box sat atop the grandstand.38 The ballpark included “12 turnstiles in all, four being placed at each of the three entrances.”39 Patrons entering the right-field pavilion walked “directly up a short flight of steps,” while those in the left-field pavilion walked “beneath the grandstand, and along a cement walk.”40 The ballpark included “five large exits” to “permit the crowd to disperse quickly after the game.”41

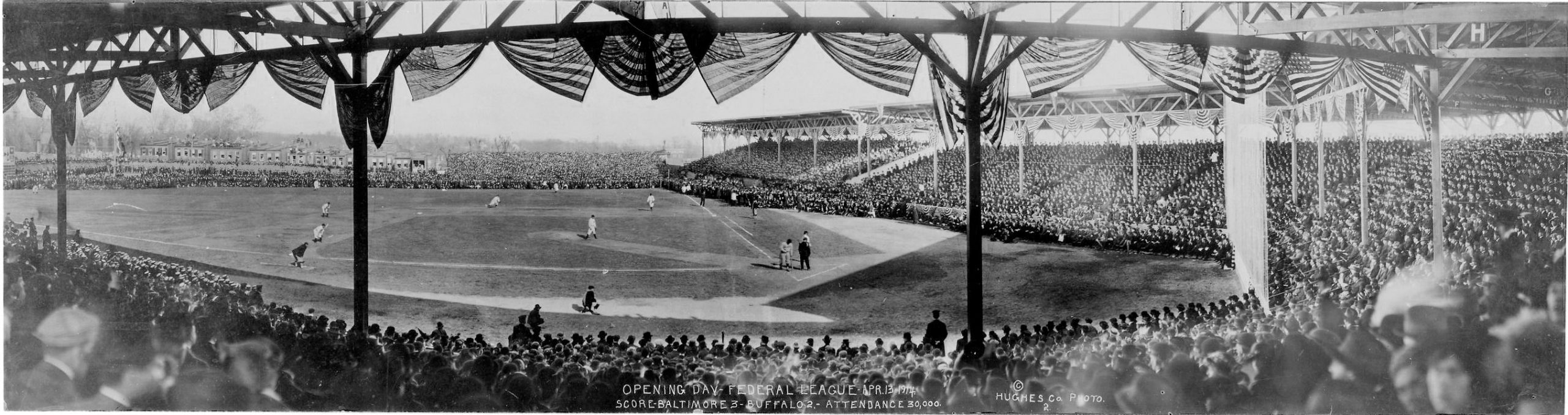

Terrapin Park, Opening Day of the Federal League season April 13, 1914 – Baltimore 3, Buffalo 2. (Courtesy of the Baltimore Orioles.)

Opening Day at Terrapin Park was April 13, 1914, with Mayor Preston declaring the afternoon a municipal holiday to “enable the officials and employees to attend the opening game of the Federal League baseball season.”42 Before the game, the city held a parade in honor of both teams, with thousands lining the parade route “east on Baltimore street from Calvert, to Holliday, to Lexington, to St. Paul street, south on St. Paul street to Baltimore, to Charles, north on Charles to North avenue east to the York road to the grounds.”43 Paid admissions to the park totaled 27,692, with 12,000 spectators standing and several thousand outside the ballpark, unable to get in.44 “The big grandstand, the right and left field pavilions, the bleachers were taxed to their capacity,” with “hundreds of chairs on the field that were pressed into service.”45 According to the Baltimore Sun, “[E]verybody was happy, none more so apparently than the ticket scalpers who did a thriving business,” with fans paying $3 for a $1 ticket.46 The Terrapins defeated the Buffalo Buffeds 3-2, and “Baltimore was universally first in the standings.”47 According to the Baltimore Sun, “[T]he tremendous crowd, the wild enthusiasm and terrific rooting rivaled the glorious days of the old Oriole championship team 17 years ago.”48 Across from Terrapin Park on Twenty-Ninth Street, the International League Orioles lost an exhibition game to the National League New York Giants, 3-2, at Oriole Park (IV) before an audience of 3,000.49

More than 45,000 attended all three games of the opening series at Terrapin Park.50 As noted by the Baltimore Sun, “[T]hat’s going some for a city which has been considered a poor baseball town in the ranks of organized ball.”51 Ticket prices were: bleacher seats, 25 cents; pavilion seats, 50 cents; grandstand seats, 75 cents; and reserved grandstand seats and box seats, $1.52 After the first homestand, the club built a higher fence in center field “in order to give batters a better view of the ball.”53 The club also added “a screen on the grandstand to shield the right fielders from the sun.”54

The Terrapins were in first place on May 5, 1914, and remained there for over a month before dropping to third place.55 In September they were in a tight pennant race with Chicago, Indianapolis, Brooklyn, and Buffalo.56 The Sun noted:

That the Federal teams are so evenly matched is wonderful when it is considered that managers were forced to search all the leagues in the country for players to fill out their rosters. A walkaway for any team in the Independent circuit would have caused interest in the third major to slacken, but the great fight which is now being waged, with Baltimore a very strong contender, makes the first real race of the invaders very attractive.57

The Terrapins ended the season in third place, 4½ games behind the pennant winner, Indianapolis.58 During the season the ballpark hosted other baseball events. In June a local school league, sponsored in part by the Sun Newspapers, played a championship series at Terrapin Park in front of 2,000 students.59 On June 30 Terrapin Park hosted a game between members of the Baltimore City Police and the Baltimore Sun and Evening Sun, for the benefit of the Babies’ Milk and Ice Fund.60 On July 14 the Terrapins “invited the inmates of Baltimore orphanages to witness the double-header between the Diamondbacks and the Buffeds.”61 In 1915 the use of Terrapin Park was expanded to include boxing matches and movies.62

Hope for the Terrapins seemed strong for Baltimore as the 1915 Federal League season began. In the offseason, the Terrapins had acquired future Hall of Fame pitcher Chief Bender, who it was thought could help bring a championship to Baltimore.63 On Opening Day an impressive crowd of 18,391 watched the Terrapins lose 7-5 to the Newark Peppers (formerly the 1914 league champion Indianapolis Hoosiers).64 The 1915 season did not turn out as Baltimore fans had hoped and attendance fell off drastically.65 Bender won only four games and posted 16 losses.66 By the end of the season, Baltimore was in last place, losing more than twice as many games as they won, with a record of 47-107, and 40 games behind the pennant-winning Chicago Whales.67

But in the end it really did not matter, as the Federal League folded after the season. Hanlon and other Terrapin Club officials continued in US District Court an action filed earlier by the Federal League, challenging Organized Baseball’s hold on the national pastime, claiming it violated the Sherman Anti-Trust Act.68 Ultimately, in 1922, the Supreme Court dismissed the Federal League challenge, holding that baseball was not subject to the Sherman Act because baseball was a state activity and did not qualify as interstate commerce.69

The major-league Baltimore Terrapins lasted just two seasons. It would not be until 1954 that what was then known as major-league baseball would return to Baltimore, when the city got its second American League franchise, the original 1901 Milwaukee franchise, which moved to St. Louis in 1902.70

The two years the Federals were in Baltimore proved most difficult for Dunn and his International League team. In 1914 Dunn signed, and then sold, Babe Ruth out of St. Mary’s Industrial School for Boys to play for his International League Orioles.71 As reported in the Baltimore Sun:

The Oriole magnate signed another local player yesterday. The new Bird is George H. Ruth, a pitcher, who played with teams out the Frederick road. Ruth is six feet tall and fanned 22 men in an amateur game last season. He is regarded as a very hard hitter, so Dunn will try him out down South.72

Nicknamed Babe because of his youth, and as a reference early on to his being “Jack Dunn’s Babe,” Ruth was sold by Dunn to the Boston Red Sox, and assigned to the International League Providence Grays.73 Dunn had received permission from the league to sell Ruth and other Orioles to help pay off the considerable debt he had incurred to run his team once the Terrapins took up residency across the street from him.74 Before the 1915 season, unable to compete with the Federal League’s hold on Baltimore baseball fans, Dunn moved his International League Orioles to Richmond, Virginia.75 After the Federal League’s demise, he purchased the Jersey City International League franchise and moved it to Baltimore.76

In March 1916, Dunn purchased Terrapin Park, which then became the fifth Baltimore ballpark known as Oriole Park. Wrote the Sun:

It is believed that Dunn agreed to pay about $30,000 for the stands, which, with the improvement made upon the grounds, cost the 600 Terrapin stockholders in the neighborhood of $90,000. Of course, Dunn got a bargain, for there never were more comfortable or more substantial wooden stands ever built than those put up for Baltimore’s representative in the Baby Major.

The lot, of course, was not included in the sale because that belongs to Ned Hanlon. Dunn will pay $4,000 a year rent for the lot, but has the privilege of buying it any time within the next eight years for $65,000.77

Hanlon sold Dunn the land on which the ballpark sat in January 1921.78

The Orioles played respectable ball during 1916 season, posting a record of 74-66, and placing fourth, eight games back of the league champion Buffalo Bisons.79 The 1916 season saw the first of a dozen exhibition games that Babe Ruth would play at Oriole Park (V),with his final exhibition-game appearance there on May 1, 1930. On April 18, 1919, while with Boston, Ruth hit four home runs in an exhibition game against the Orioles, which the Red Sox won 12-3.80 The next day he hit two more home runs, with five hit in a row (the last three at-bats of the first game and the first two at-bats of the second game).81

Dunn helped lead the charge to bring Sunday baseball to Baltimore. In 1918 he was arrested for violating Baltimore’s blue laws, which restricted on Sundays the charging of admission to public events like baseball.82 In 1910 Dunn built a ballpark in Baltimore County at Back River Park, to avoid the city’s blue laws, and allow his Orioles to play baseball on Sundays.83 By 1921 Dunn had won the right to stage baseball games on Sundays in Oriole Park (V).84

Beginning in 1919, Dunn built his Orioles into an International League powerhouse, winning over 100 games that year and the first of seven straight league championships.85 In 1920 Dunn signed future Hall of Fame pitcher Robert Moses “Lefty” Grove. During his five seasons with the Orioles, Grove won 108 games and lost only 36.86 Dunn sold Grove to the Philadelphia A’s after the 1924 season for $100,600, the extra $600 added “to make it a sum greater than what the Yankees had paid Boston for Babe Ruth.”87 Grove would win 300 games in the major leagues.88 Dunn died suddenly after the 1928 season.89 During their final seasons at Oriole Park (V), 1926 until 1943, the International League Orioles never again won the league championship.90

In 1939, the Baltimore Elite Giants began playing their home games at Oriole Park (V),91 once they were “finally accepted as occasional Sunday afternoon tenants of Oriole Park.”92 That season, the Elite Giants played 14 home games at Oriole Park (V) against Negro National League teams and two home games against Negro American League opponents (Cleveland Bears).93 They also played four playoff games at the ballpark, including a September 10, 1939, doubleheader against the Newark Eagles, with the Elite Giants winning both games by scores of 7-3 and 5-2,94 as well as a September 17, 1939, doubleheader against the Homestead Grays, with the Elite Giants winning the first game 7-5, and the teams playing to a 1-1 tie in the second game (five innings, game called because of a 6:00 P.M. curfew).95 That season, the Elite Giants went on to win the Negro National League title, defeating the Homestead Grays at Yankee Stadium in the final game.96

In addition to games played at Oriole Park (V), beginning in 1938, the Elite Giants also played home games at Bugle Field, located in East Baltimore at the intersection of Federal Street and Edison Highway.97 There currently are no recorded contests played at Bugle Field in 1939 between the Elite Giants and other major-league Black teams.98 To the extent the Elite Giants played games against non-league (semipro, amateur) opponents at Bugle Field in 1939, those games appear to have been unrecorded in the press.99

The Elite Giants’ tenure at Oriole Park (V) came to an end on May 10, 1942, after a fight between fans caused minor damage to the ballpark and the owners of the ballpark decided to disallow any more Negro League games at Oriole Park (V).100 The Elite Giants continued to play home games at Bugle Field through the 1949 season.101 Bugle Field was demolished in October 1949,102 and in 1950 and 1951, the Elite Giants played their final two seasons at Westport Stadium, a newly-constructed ballpark located on Annapolis Road in Westport, just south of the intersection of I-95 and I-295.103

On July 4, 1944, Oriole Park (V) was destroyed by a fire.104 The Baltimore Sun reported on the destruction of the ballpark:

Fire of undetermined origin razed the stands of famed Oriole Park, home of the Baltimore International League Club, today, causing a loss estimated by club officials at $150,000.

The wooden stands burned so rapidly that within little more than an hour only charred and smoking timbers remained around the field where Jack Dunn once led his Orioles to seven straight league pennants, and where he developed such famous stars as Babe Ruth, Lefty Grove, Joe Boley, Tommy Thomas, Max Bishop and others.105

The International League Orioles won the pennant in 1944, beginning their season at Oriole Park (V),106 and finishing their season (and subsequent seasons through 1953) at Baltimore Municipal Stadium, which later became Memorial Stadium.107

The site now is occupied by row houses, the Barclay Elementary School, and Peabody Heights Brewery.108 In 2015 Peabody Heights Brewery hired the company that performed the original survey of Terrapin Park to help determine the exact, former location of home plate:

Home plate, it turns out, stood in what is now a grass strip, midway up the east side of the 2900 block of Barclay St. The spot faces windows on the Barclay Elementary/Middle building. The pitcher’s mound was not far from the south-facing wall of what is now the Peabody Heights Brewery, the former Royal Crown bottling plant.

The surveyors relied upon a well-preserved 1914 original survey of the park created by the S.J. Martenet Co., a firm that remains in business in Baltimore’s Mount Vernon neighborhood. They found the coordinates to pinpoint where the base lines would have been.

“We laid out the base lines, bleachers and grandstands in 1914,” said Joel Leininger, an owner of Martenet. (It’s his daughter who assisted in this week’s resurvey.) He told me the outlines of the park property came into discussion recently when a neighboring building was sold. When land is transferred, it is customary for it to be resurveyed. It was this resurvey of the former DuPont warehouse that sparked the current conversation about the ballpark.109

Beginning in 2017, the SABR Baltimore Babe Ruth Chapter has held its annual SABR Day meetings at Peabody Heights Brewery, in an area of the brewery that was once the left-field pavilion of Terrapin Park and Oriole Park (V).110 In 2020, the Baltimore SABR chapter placed an historic marker commemorating “Old Oriole Park” in the brewery’s beer garden.

Notes

1 Byron Bennett, “Baltimore’s Other Major League Ballfield – Terrapin Park/Oriole Park,” deadballbaseball.com, December 6, 2012, Baltimore’s Other Major League Ballfield – Terrapin Park Oriole Park – Deadball Baseball

(accessed January 29, 2024); Bob Luke, The Baltimore Elite Giants (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press University Press, 2009), 70, 81.

2 Byron Bennett, “The Six Different Ballparks Known as Oriole Park,” deadballbaseball.com, December 30, 2013. The Six Different Ballparks Known As Oriole Park – Deadball Baseball (accessed January 29, 2024).

3 Byron Bennett, “The Six Different Ballparks Known as Oriole Park.”

4 The future owners of the New York Highlanders/Yankees bought the Baltimore franchise and moved it to New York.

5 “Will Old League Buy? Receivers Appointed to Sell the Stands at New Baseball Park,” Baltimore Sun, October 21, 1902: 6.

6 “Promise a Good Team: Hanlon to Have One in the Eastern League, Gets the Baseball Park,” Baltimore Sun, January 30, 1903: 9.

7 In the succession of ballparks by this name, it has come to be known as Oriole Park (IV).

8 “Promise a Good Team.”

9 baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Ned_Hanlon (accessed January 2, 2020).

10 James H. Bready, Baseball in Baltimore, The First 100 Years (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press University Press, 1977), 116-117; “Dunn as Team Owner: Jack Wants to Buy Local Club’s Franchise, Hanlon Says He Will Sell, but the Manager Declares He Must Get ‘Proper Price,’” Baltimore Sun, October 8, 1909: 10; “Hanlon Is Sole Owner: He Buys Up All the Stock Of Baltimore Baseball Club/Frank And Winternitz Sell, Hughey Jennings Also Lets His Bit Go and Jack Dunn May Become Real Oriole Magnate,” Baltimore Sun, November 11, 1909: 10; “Jack Dunn Buys Orioles: Former Manager Is Sole Owner of Baltimore Baseball Club, Old Robbie Is a Director, Charles H. Knapp Is Third Director and Secretary and Treasurer -New Faces to Be Seen,” Baltimore Sun, November17, 1909: 10.

11 “Federal League Is Formed in The West,” Baltimore Sun, March 9, 1913: A1.

12 “Major League Ball Offered Baltimore: Federal League, After One Season, Intends to Invade the East, This City Can Get Franchise, Independent Organization Said to Have Ample Financial Backing, and the Intention to Make Itself Second to None – Plenty of Players to Pick From,” Baltimore Sun, October 21, 1913: 6.

13 “Major League Ball Offered Baltimore.”

14 “Big League Plan Launched: Articles of Incorporation of Federal Club,” Baltimore Sun, October 28, 1913: 16.

15 “Big League Plan Launched.”

16 “Baltimore Is Admitted to Federal League,” Baltimore Sun, November 2, 1913: S1.

17 “Ball Park Plans Scanned,” Baltimore Sun, November 8, 1913: 7.

18 “Ball Park Plans Scanned.”

19 “Hanlon With Federals: Famous Old Baseball Manager Enthusiastic for New League,” Elected Director of Club, Baltimore Sun, November 13, 1913: 12.

20 “Hanlon With Federals.”

21 “Club Stock for ‘Fans’ Federal League Preferred Will Be Sold at $10 a Share, Hanlon Demanded This Move,” Baltimore Sun, November 20, 1013: 2.

22 “Hanlon Buys Ground for Feds’ Ball Park, Deal Is Closed for Tract Required to Make Playing Field Sufficiently Large,” Baltimore Sun, December 31, 1913: 5.

23 “New Ball Park Plans In, City Council Asked to Authorize Big Buildings at York Road and Twenty-Ninth Street,” Baltimore Sun, January 13, 1914: 5.

24 “New Ball Park Plans In.”

25 “New Ball Park Plans In.”

26 “Russell Ford, Edgar Willet and Howard Camnitz Sign With Federal League; to Break Ground Today; Mayor Preston Will Start Work at Federal League Park, Baltimore Sun, January 21, 1914: 11.

27 “Park Bids Are Open, Baltimore Feds Will Award Contract Saturday for New Home, to Seat Nearly 13,000 Fans,” Baltimore Sun, January 27, 1914: 9.

28 “Park Bids Are Open.”

29 “Schoolboys to Root, Friends Will Send a Squad Of 100 to Terrapins’ Opening Game, Fans Inspect New Ball Park,” Baltimore Sun, March 16, 1914: 8.

30 “It’s ‘Terrapin Park,’ Baltimore Federal Magnates Decide Upon Name for Their Home; All Grandstand Seats Sold,” Baltimore Sun, March 18, 1914: 8.

31 “It’s ‘Terrapin Park.’”

32 “It’s ‘Terrapin Park.’”

33 “Work Progressing at Terrapin Park,” Baltimore Sun, March 29, 1914: S2.

34 “Work Progressing at Terrapin Park.”

35 “Work Progressing at Terrapin Park.”

36 “Terrapin Park Is Ready to Welcome Baltimore Fans,” Baltimore Sun, April 12, 1914: S2.

37 “Terrapin Park Is Ready.”

38 “Terrapin Park Is Ready.”

39 “Terrapin Park Is Ready.”

40 “Terrapin Park Is Ready.”

41 “Terrapin Park Is Ready.”

42 “Municipal Holiday Today,” Baltimore Sun, April 10, 1914: 14.

43 “28,000 See Contest; Inspiring Sight at Terrapin Park as Federal League Season Opens,” Baltimore Sun, April 14, 1914; 1.

44 “28,000 See Contest.”

45 “28,000 See Contest.”

46 “28,000 See Contest.”

47 Bready, 127.

48 “Baseball Features of the Day,” Baltimore Sun, April 14, 1914: 1.

49 “Baseball Features of the Day.”

50 “More Than 45,000 Fans Attend the Terrapin Games, Baltimore Sun, April 19, 1914: SS1.

51 “More Than 45,000 Fans Attend.”

52 Classified Ad 7, Baltimore Sun, April 18, 1914: 1.

53 “Zinn Will Be Out of Game Several Days,” Baltimore Sun, April 25, 1914: 11.

54 “Zinn Will Be Out.”

55 “Brady, 127.

56 “Baseball Races Close, Federal, National and International Furnishing Thrills, Baltimore Strong Contender,” Baltimore Sun, September 17, 1914: 5.

57 “Baseball Races Close.”

58 Brady, 127.

59 “School No. 42 Victor: Defeats No. 48 in Initial Championship Ball Game; 2,000 Children See Struggle,” Baltimore Sun, June 23, 1914: 14.

60 “Dare ‘Cops’ to Take It; Game of Ball with Newspaper Men to Be Red-Hot One, for Babies’ Milk and Ice Fund,” Baltimore Sun, June 18, 1914: 4.

61 C. Starr Mathews,”Orphans Will See Games at Terrapin Park Today,” Baltimore Sun, July 14, 1914: 5.

62 “Kid Must Like the Air: Williams Won His Greatest Battles in Outdoor Rings, Scored Three Knockouts,” Baltimore Sun, July 21, 1915: 5; “Taylor Badly Battered, New Yorker No Match for Kid Williams, King of Bantams, Knocked Down in Thirteenth,” Baltimore Sun, July 25, 1915: I10; “Dunn Buys Terp Park, Will Take Possession of Federal League Plant April 1, Price Believed About $30,000,” Baltimore Sun, March 4, 1916: 11.

63 “Bender Will Pitch for the Terrapins, Player Committee Decides Indian Is Needed to Bolster Up Twriling Staff, Signed Two-Year Contract,” Baltimore Sun, December 8, 1914: 1.

64 “Terrapins Lose Opening Game, Newark Peppers Capture First Contest of Season Before 18,391,” Baltimore Sun, April 11, 1915: 1.

65 “Now Is The Time to Assure Ourselves of a Permanent Place on the Baseball Map – And IF It Is Not Done Now, It Will Be Never,” Baltimore Sun, June 7, 1915: 6; “Ten-Cent Ball Today, New Prices to Go Into Effect Here at Terrapin Park, Two Games for the One Price,” Baltimore Sun, August 13, 1915: 12.

66 Bready, 128.

67 Bready, 128.

68 “Terrapins to Keep Up Fight, Baltimore Trying to Block Baseball Settlement, Says Report, Would Continue Anti-Trust Suit,” Baltimore Sun, December 23, 1915; 14; “Terrapins May File $900,000 Suit Today, Case Against O.B. and Federal Pacifists Will Be Fought in Philadelphia,” Baltimore Sun, March 17, 1916: 10. “Terps Fire Opening Gun in Suit Against Organized Ball: Cost O.B. a Million to Put Out Federals, Terms of Peace Pact Out in Trial of Baltimoreans’ $900,000 Suit, Terps Ignored, They Claim,” Baltimore Sun, June 12, 1917: 8.

69 Federal Baseball Club v. National League, 259 U.S. 200 (1922).

70 It should be noted that on December 16, 2020, Baseball Commissioner Robert Manfred announced that Major League Baseball had officially elevated the Negro Leagues to major-league status for the period 1920 = 1948. MLB Press Release, December 16, 2020, www.mlb.com/press-release/press-release-mlb-officially-designates-the-negro-leagues-as-major-league (last accessed January 30, 2024). Accordingly, prior to the American League Orioles coming to Baltimore in 1954, the city had two other major-league teams – the Baltimore Black Sox and the Baltimore Elite Giants – who played during at least a portion of the period 1920 to 1948.

71 Bready, 134.

72 Dunn Now Trying to Bolster Club,” Baltimore Sun, February 15, 1914: S3.

73 Bready, 134-135.

74 “3 More Orioles Sold, Ruth, Shore And Egan Purchased by the Boston Red Sox, They Leave the Nest Tonight,” Baltimore Sun, July 10, 1914: 5; “None to Quit, He Says; International President Declares All His Clubs Will Stick, Approves Sales by Jack Dunn,” Baltimore Sun, July 13, 1914: 5.

75 “Richmond Gets Orioles, Virginia League Accepts Offer to Let in International, Jack Dunn to Head Company,” Baltimore Sun, January 13, 1915: 11.

76 Bready, 143.

77 “Dunn Buys Terp Park: Will Take Possession of Federal League Plant April 1, Price Believed About $30,000,” Baltimore Sun, March 4, 1916: 11.

78 “Jack Dunn Lifts Option on Baseball Grounds,” Baltimore Sun, January 3, 1924: 12.

79 baseball-reference.com/bullpen/1916_International_League_season (accessed January 4, 2020).

80 Bready, 139.

81 Bready, 139.

82 “Jack Dunn Under Fire, Charged with Violating Sunday Law at Oriole Park, Sold Admissions, Is Charged,” Baltimore Sun, July 16, 1918: 5; “Birds Trim the Leafs, Sunday Baseball in City Inaugurated with Victory, About 9,000 Cheer Dunnmen,” Baltimore Sun, June 17, 1918: 5.

83 “To Have Sunday Ball, Dunn Will Build Stand and Grounds Opposite Prospect Park; to Lease the Property Today,” Baltimore Sun, March 11, 1910: 10; Bready, 118.

84 “Great Throng at Oriole Park Attests Popularity of Game: Largest Sunday Baseball Crowd Overflows Stands and Fields – Gates Are Closed Momentarily and Thousands Turn Away,” Baltimore Sun, April 21, 1925: 8.

85 Bready, 145.

86 baseball-reference.com/register/player.fcgi?id=grove-002rob (accessed January 5, 2020).

87 Bready, 154.

88 Bready, 154.

89 Bready, 186.

90 James H. Bready, The Home Team Our Orioles (25th Anniversary Edition) (self-published, 1959), 44.

91 Email from Gary Ashwill, Co-Creator & Lead Researcher, Seamheads, December 19, 2022.

92 Bready, Baseball in Baltimore, 175; “Stars to Meet Giants in National Negro Loop at Oriole Park Today,” Baltimore Sun, June 27, 1937: S3; “Elite Giants Play Homestead Grays Today,” Baltimore Sun, July 25, 1937: SS7; “Elite Giants to Open Season Next Sunday,” Baltimore Sun, May 3, 1942: S3.

93 Email from Gary Ashwill, Co-Creator & Lead Researcher, Seamheads, December 19, 2022.

94 Ralph Boyd, “Elites Whip Eagles to Gain Championship Series,” Afro-American, September 16, 1939: 22.

95 Art Carter, “Elites, Grays Tied in National League Title Series,” Afro-American, September 23, 1939: 19.

96 Brady, Baseball In Baltimore, 175.

97 Luke, 32; Brady, Baseball In Baltimore, 174.

98 Email from Gary Ashwill, Co-Creator & Lead Researcher, Seamheads, December 19, 2022.

99 Email from Gary Ashwill, Co-Creator & Lead Researcher, Seamheads, December 19, 2022.

100 Luke, 70, 81.

101 Luke, 121.

102 Byron Bennett, “Bugle Field – Home of the Baltimore Elite Giants,” deadballbaseball.com, October 6, 2013, Bugle Field – Home of the Baltimore Elite Giants – Deadball Baseball (accessed January 29, 2024).

103 Byron Bennett, “Westport Stadium – Baltimore’s Last Negro League Ballpark,” deadballbaseball.com, October 28, 2013, Westport Stadium – Baltimore’s Last Negro League Ballpark – Deadball Baseball (accessed January 29, 2024).

104 “Oriole Ball Park Destroyed by Fire: Baltimore Team Loses Uniforms and Trophies,” Baltimore Sun, July 5, 1944: 19.

105 Oriole Ball Park Destroyed by Fire: Baltimore Team Loses Uniforms and Trophies.”,

106 Brady, The Home Team, 45.

107 Brady, Baseball In Baltimore, 204-208; Jesse A. Linthicum, “Sunlight on Sports,” Baltimore Sun, July 5, 1944: 15.

108 Byron Bennett, “Baltimore’s Other Major League Ballfield – Terrapin Park/Oriole Park”; Byron Bennett, “The Six Different Ballparks Known as Oriole Park.”

109 Kelly Jacques, “Surveyors Find Home in a City Neighborhood: Documents Show Layout of Oriole Park, Which Burned In ’44,” Baltimore Sun, May 2, 2015: A3; David B. Stinson “Surveying Site of Old Oriole Park at Peabody Heights Brewery” (May 2, 2015), surveying-site-of-old-oriole-park-at-peabody-heights-brewery.

110 David B. Stinson, “Drinking Beer in The Left Field Tasting Room at Old Oriole Park,” davidbstinsonauthor.com, July 31, 2015, drinking-beer-in-the-left-field-tasting-room-at-old-oriole-park (accessed January 29, 2024).