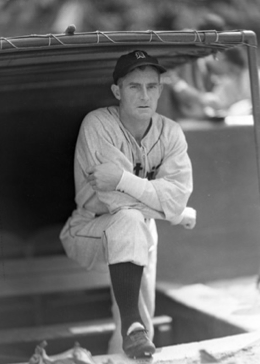

Del Baker

Del Baker was born and raised about as far from the big leagues as possible, yet he ultimately became famous as baseball’s canniest sign-stealer. Along the way, he also managed the Detroit Tigers to within a whisker of a world championship.

Del Baker was born and raised about as far from the big leagues as possible, yet he ultimately became famous as baseball’s canniest sign-stealer. Along the way, he also managed the Detroit Tigers to within a whisker of a world championship.

In 1892, Delmer David Baker was born in Sherwood, Oregon, then a small rural community a few miles southwest of Portland. According to a 1938 story in The Sporting News, Baker’s father owned an 86-acre farm, a portion of which he cleared for a baseball field where Del and his four brothers played each summer; the Baker boys anchored the sandlot Sherwood White Sox. For some years after making baseball his profession, Baker would return to Oregon during the offseason and tend the family’s hops crop (with plenty of time for hunting, his favorite hobby). Later, San Antonio would become his offseason home.

It doesn’t seem that the young Del Baker was counting on baseball, though. After attending Portland’s Benke-Walker Business College, he went to work in 1909 as a bookkeeper in tiny Wasco, Oregon, on the other side of the Cascades from his boyhood home. “Between times, while keeping books in Wasco, he caught for the town team. There, Bunk Holman, a scout for Spokane, signed Baker to a contract with Spokane.”1

According to the published record, Baker’s first professional engagement came in 1911, with the Helena Senators if the Class D Union Association (Organized Baseball’s lowest level). After another season there, Baker moved up to Class A in 1913 with the Western League’s Lincoln Railsplitters. He batted .260 with Lincoln and must have impressed someone important, because in August he was “released to” the Detroit Tigers, and would spend each of the next three seasons backing up the Tigers’ first-string catcher, Oscar Stanage.

After those three seasons, Baker’s career batting average in the majors stood at .209 … and he would not get a chance to better that mark. Before spring training in 1917, the Tigers farmed him out to the San Francisco Seals of the Pacific Coast League. He would later credit manager Harry Wolverton with teaching him “more baseball than any other man.”2 Back in the minors, Baker hit the way he’d hit in the minors before: decently. But in 1918, he didn’t hit much of anything; instead he served in the US Navy, as so many other professional baseball players did. In 1919 Baker returned to the Pacific Coast League, but this time with his hometown team, the Portland Beavers. After three seasons there, Baker spent a season with Mobile in the Southern Association, then returned to the PCL for three more seasons, this time with the Oakland Oaks.

Baker was back in Oakland in 1928, but spent most of that season as player-manager with the Ogden Gunners in the Utah-Idaho League. The Gunners finished 57-59, and the next season Baker returned to merely playing; this time with Fort Worth in the Texas League.

In 1930, though, Baker got another shot at managing. Staying in the Texas League, he was the player-manager of the Beaumont Exporters, one of Detroit’s top farm clubs.

That season, Beaumont finished without many top prospects (although the Exporters did feature Ox Eckhardt, one of the great minor-league hitters of all time). In ’31, though, with Baker still running the club, future major-league star Jo-Jo White anchored the lineup and the Exporters finished 94-65. The best was yet to come. In 1932 Schoolboy Rowe and Luke “Hot Potato” Hamlin anchored the pitching staff, outfielders Pete Fox and Paul Easterling starred in the outfield … and young Hank Greenberg topped the league with 39 home runs, garnering MVP honors. The Exporters, the youngest team in the league, went 100-51 in the regular season, then swept Dallas for the Texas League championship.

In 1933 Greenberg, Fox, and Rowe all graduated to the major leagues, and Del Baker was right there with them, in the majors for the first time since 1916 and coaching third base for his old club. Greenberg didn’t open the season as the Tigers’ everyday first baseman, though. That job was held by Harry “Stinky” Davis, and manager Bucky Harris wasn’t ready to make a change. Maybe he didn’t trust Greenberg’s bat, or maybe he didn’t trust his fielding; by all accounts, Greenberg was a mess at first base.

But Greenberg worked hard on his defense, and Baker was right there with him. “He couldn’t catch a pop fly when he first came up with the Tigers,” Tigers pitcher Elden Auker recalled in his memoir. “Every time he would try to catch a pop fly, he would throw his head back. Those pop flies gave him fits. … Hank went to the ballpark at 9:00 every morning and had Baker hit him pop flies with a fungo bat. I bet Baker hit Hank Greenberg a million pop flies. Hank was determined to perfect the art of catching a pop fly, and he worked so hard he got to the point where he could catch those things in his jockstrap.”3

Whatever the reason —and it probably had a lot to do with Davis’s stinky hitting —Harris finally relented in May, with Greenberg taking his place in the annals of the franchise.

Not that Del Baker was finished helping Greenberg.

As a rookie, Greenberg hit only a dozen home runs. As a sophomore, he established himself as a star with 26 homers and 63 doubles. And in 1935, his third season, Greenberg finished with 36 homers and 170 RBIs; both figures led the American League, and Hank took Most Valuable Player honors. The next spring, he held out during spring training. In late March, the New York World-Telegram’s Joe Williams reported a hotel-lobby conversation he’d overheard in Sarasota:

“ ‘The Tigers didn’t have any trouble signing Del Baker, did they?’ asked Mr. Herb Pennock, the old pitcher, lifting a provocative eyebrow.

“‘What’s Baker got to do with Greenberg?’ grumbled Jimmy Foxx. ‘He’s just a third base coach.’

“ ‘Just this,’ answered Pennock. ‘Baker called almost every pitch for Greenberg last season, and if he’s holding out for more dough Baker ought to hold out.’

“It then came out that from his position in the coacher’s box back of third base, Baker, most expert of modern signal stealers, would inform Greenberg what the pitch was going to be —a fast ball or a curve.

“If it was to be a fast ball Baker would bark, ‘Come on Hank, paste this one.’ The word ‘come’ always denoted a fast ball. If the pitch was to be a curve ball he would yell, ‘All right, Hank, get on now!’ In this case the word ‘get’ was the tip-off.

“Of course there were some pitchers who covered up so well that Baker couldn’t discover what they were going to throw, but the athletes are pretty well agreed he was able to find out what most of them were going to throw and that this information was of great help to Greenberg, who is known as a guess hitter, anyway.”

That might have been the first time that Greenberg’s heroic slugging was publicly credited, at least in part, to Baker’s uncanny ability to read pitchers. It was hardly the last. And Greenberg eventually tired of it. Shortly into 1938, a piece by Dan Daniel in the World-Telegram included these astonishing quotes from Greenberg:

“I think I have reached the point in my career at which in justice to myself I must break down some misinformation. Time and again you have written that I am strictly a guess hitter. Writers all over the circuit have spread a similar impression. And all of you have given to the fans the idea that I wait for Baker’s dope on every pitch, and unless I get the right tip from Del I do not swing.

“For this condition I am 75 per cent self-responsible. Up to now I have been quite content to let folks think I was a sort of Charley McCarthy, with Baker pulling the string. If I hit one over the fence and the boys in the dugout asked, ‘Did you get it from Del?’ I invariably replied ‘Yes.’ I believed it was helping Baker and not doing me any harm.

“But the importance of such information as I have accepted has been exaggerated. If I am to win a high place among the stars of the game it must come with the breaking down of this untrue conception of my batting policy and ability and your telling the fans the truth. In short, I am nobody’s dummy and I ask you to write that in the World-Telegram.”

Greenberg went on to say that while he’d gotten a few tips from Baker in 1937, he was the only Tiger who did. What’s more, with Baker, the Yankees’ Art Fletcher, and other coaches looking for clues, the “older hurlers” weren’t giving anything away, leaving only “an occasional rookie” as victims.

While Greenberg’s reliance on Baker’s tips had probably been greatly overstated, it’s probably also true that Greenberg —or maybe Daniel; you never know about these things —was understating Baker’s impact, generally. Shortstop Dick Bartell would join the Tigers in 1940, and later wrote that Greenberg, Rudy York, and Pinky Higgins all wanted Baker’s tips. Bartell also suggested that the Tigers hit Bob Feller well in 1940 because Baker was reading all of Feller’s pitches.4

By the time Bartell arrived in Detroit, Baker was actually managing the Tigers.

Back in 1933, Baker had unofficially filled in as manager for two games. In 1936 he officially managed the Tigers for 34 games while Mickey Cochrane recovered from what’s been described as a nervous breakdown. But Baker actually took over the club starting on the 10th of June, managed for more than a month in Cochrane’s absence, and —after Cochrane returned just briefly in mid-July —took over for most of the rest of the season.

Cochrane came back strong in 1937, as both the Tigers’ manager and No. 1 catcher. But on May 25 he suffered the terrible beaning that ended his playing career. Baker took over again, and (again, officially) he managed 64 of the Tigers’ remaining games (unofficially, it might well have been more than that).

In 1938 Cochrane returned to the dugout. But after getting blown out by the Red Sox on August 6, the Tigers’ record stood at 47-51 and owner Walter Briggs concluded a tense meeting with his manager by firing him. Del Baker, with a winning record in each of his interim stints, would take over immediately. And true to his history, Baker guided the Tigers to a 37-19 record the rest of the way, for a first-division finish. The next season would be relatively uneventful, as the Tigers again finished with a winning record but fell to fifth place.

Some owners might have fired Baker right then. In fact, at least one owner never would have hired him in the first place. Frank Navin had owned the Tigers before being killed in a horse-riding accident shortly after the 1935 season. According to Joe Williams, Navin once turned to American League President Will Harridge and said of Baker, “See that fellow at third? Well, that’s the smartest man in baseball.” Still, Baker said in 1941, “Navin once told me I never should be a manager. Even now I don’t think I’m a manager. I can’t go in there and pitch for the pitchers, and I can’t go in there and hit for the hitters. I am just a guy who is sitting in the dugout with the other fellows, trying to figure out how we can get in the World Series. If that makes you a big-league manager, I am a big-league manager.”5

But Briggs had no such qualms about Baker’s worthiness as a manager, and stuck with him despite the fifth-place finish. Which would pay off in a big way.

Heading into 1940, Baker had a big problem: One of his best hitters was Rudy York, a catcher. But York was a lousy catcher. And of course Baker already had, in Hank Greenberg, the best first baseman in the world. Tigers general manager Jack Zeller had an idea. If Greenberg would agree to play left field —which he did, in return for a healthy bonus —York could shift to first base.

It was a brilliant move. Greenberg wasn’t a disaster in left field, while York played in every single game and drove in 134 runs. It’s not clear that Baker was a big fan of the switch, though; in Greenberg’s autobiography, he tells a story about getting pulled from a game after muffing a play, and telling Zeller that if Baker did that again, he just wouldn’t play out there any more. It didn’t happen again.6

Bartell wasn’t a big fan of Baker’s, either. He wrote in his book, “I learned that you couldn’t always believe what he told you. He would go behind your back, talking about you to other players. He asked me so many times what I thought about somebody or some situation. I didn’t like that.”7

Billy Rogell, Bartell’s predecessor at shortstop, also didn’t seem to have gotten on well with Baker.8 Nor did Jo-Jo White or Rudy York. On the other hand, Charlie Gehringer would later recall, “He was the last manager I played for. I liked to play for him. He was all baseball, morning, noon, and night.”9

In July 1939, Baker’s wife, Mamie, had a dream. “It was clear as day,” she said a year and a half later, “and I saw Detroit winning the game that gave them the pennant. I woke up half choking, but fully convinced that the boys couldn’t miss —after that.”10

Mamie Baker’s dream came true in 1940, on September 27. Not that it was easy. With three games left on their schedule, the Tigers held a two-game lead over the second-place Indians. The Tigers and Indians were slated to end the season with a three-game series in Cleveland. There could be no tie; if the Tigers could win just once, they would clinch the pennant, but the infamous “Cleveland Crybabies” could still take the pennant with a sweep.

Bob Feller would start the series opener for the Indians. But who would start for the Tigers? Two days earlier, 21-game winner Bobo Newsom had won both games of a doubleheader (he went two innings in the opener, and tossed a complete game in the nightcap). But Schoolboy Rowe and Tommy Bridges, the Tigers’ other top starters, were both well-rested. Still, there was some reluctance to start anyone good against Feller, who had already won 27 games and was widely considered the best pitcher in the league. So who should start?

To help him decide, Baker convened a meeting. Accounts differ regarding the location and what was said, but we know there was a meeting the night before the game, perhaps in the team hotel or perhaps in a local bank, to which all of the club’s nonpitchers were invited. Some Tigers favored one of the veterans, and some favored 19-year-old Hal Newhouser or 20-year-old Fred Hutchinson. And some favored a 30-year-old rookie named Floyd Giebell, who’d pitched just once since joining the club earlier in the month. On the 19th he’d tossed a complete game to beat the Philadelphia Athletics, 13-2.

Baker listened, and later that evening he told Giebell to get ready to pitch the next day. “The next day at the ballpark,” Giebell would recall, “when it was time for the pitchers to warm up —Feller and myself —they thought that maybe it was a farce or something, but it didn’t turn out that way.”11

Feller pitched well, except for Rudy York’s two-run homer in the fourth inning. But that was enough for Giebell, who —with Newhouser essentially warming up in the bullpen throughout the game —never got into serious trouble and wound up pitching a shutout to clinch the pennant. He would never win another game in the majors. (Including that loss, Feller went just 3-5 against the Tigers in 1940, with a 5.33 ERA that was far higher than his mark against any other club in the league. According to Bartell, Baker had been calling Feller’s pitches all season, having noticed that Feller gripped his fastball and curveball differently.)

The Tigers faced the Cincinnati Reds in the World Series, and took the opener in Cincinnati behind the strong pitching of colorful Bobo Newsom. That night, though, Newsom’s father suffered a fatal heart attack in the team hotel. Back in Detroit a few days later, the Tigers held a two-games-to-one edge and Newsom wanted to start Game Four, for his father. Baker instead selected Dizzy Trout, who’d gone just 3-7 during the regular season. Trout, Baker later explained, “showed me stuff in a late-season game that could have beaten any team in baseball.” Baker also noted that if he’d lost with Newsom in Game Four, “where would I have been?”12

Well, he lost with Trout, who gave up two runs in the first inning as the Reds eventually won, 5-2. Newsom pitched a three-hit shutout in Game Five, but Baker asked him to pitch Game Seven on short rest, and the result was a 2-1 Tigers loss. On the one hand, Baker’s explanation for holding Newsom for Game Five is questionable; if he was willing to pitch him on just one day of rest in Game Seven —the Series was scheduled for all seven games in seven days —why not pitching on two days’ rest in Game Four? On the other hand, the Tigers scored just one run in Game Seven, so it probably would haven’t mattered how much rest Newsom had.

In 1941, with Hank Greenberg in the US Army and Rudy York slumping, the Tigers fell from first in the American League in scoring to sixth, and first in the standings to a very distant fourth. The next season didn’t go any better, and Baker was fired shortly after the World Series. In his 1946 history of the Tigers, Fred Lieb simply wrote, “Baker had done a good job as Cochrane’s successor, was a handy man around pitchers, but lacked fire.”13

There had been rumors about Baker taking the helm in Cincinnati, but instead he signed on as a coach with the Indians, working under young manager Lou Boudreau. After two seasons there, Baker took the same post with the Boston Red Sox, remaining there through 1948. From 1949 through ’51, Baker was back in his old Pacific Coast League stamping grounds, managing Sacramento for a season and then San Diego for two. His ’51 Padres finished well out of the money, and Baker scouted for the Indians in 1952. But in 1953, he returned to the job for which he was probably born: coaching the bases and reading the pitchers and catchers, once more with the Boston Red Sox.

Baker’s reputation as a sign-stealer remained largely intact. Ted Williams told the following story in his 1969 memoir: “Talk about stealing signs. I was stealing Berra’s from first base one day. He was getting kind of careless with his right knee, and I was taking a pretty good lead off first so I could see him flash the signs. I’d pass it on to Del Baker coaching first, and Baker would relay it to the batter. When I got up the next inning, Berra was fuming. ‘Boy, what a bunch of dumb-ass pitchers we’ve got,’ he said. ‘Baker knows what they’re going to throw every time.’”14

Okay, so that story’s more about Williams and Berra than Baker. But Baker’s reputation might well have led to one of the more famous games in World Series history: Don Larsen’s perfect game. As Larsen wrote in his memoirs:

“During the 1956 season, I struggled with my control from time to time. I had a so-so 7 and 5 record going into the last month of the season. In a ball game against the Red Sox in Boston, late in the season, I noticed that their third base coach, Del Baker, was watching me very closely. Del had a great reputation for being able to somehow steal pitching signs, and relay them to his hitters. After some thought, I came to the conclusion that with my full pitching delivery, he was gaining an advantage for the hitters by homing in on how I held the baseball before I threw it to the plate.”15

Famously, Larsen adopted a no-windup delivery, which he used in the 1956 World Series and threw his perfecto against the Dodgers in Game Five.

There is one “problem” with Larsen’s story: He pitched against the Red Sox twice in August, and held them to just two runs in 19 innings. By his own account, though, he started using the no-windup delivery on September 3, and he did go 4-1 the rest of the way, with a 0.52 ERA.

In 1960 Baker was temporarily handed the reins of his club because the manager was suffering from “nervous exhaustion” —just like in 1936 —and needed some time off. This time the exhausted manager was Billy Jurges, who was actually fired two days later. After Baker ran the club for a week in which the Sox went 2-5, Pinky Higgins took over (for his second stint as Boston’s skipper). On the same day that Ted Williams grabbed all the headlines by homering in his last at-bat at Fenway Park, then announcing his immediate retirement, Del Baker also announced that he wouldn’t be back in 1961. He was 68, and ready to retire to San Antonio for good. He’d been in professional baseball for more than half a century.

In 1973 Baker died at his home after a long illness. According to his obituary in The Sporting News, Baker never really cared much about managing and once said, “The fate of nations doesn’t hang on the outcome of a baseball game.”

In preparing this biography, the author relied primarily on a sizable stack of clippings from Baker’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library in Cooperstown, New York. Dick Bartell’s and Hank Greenberg’s memoirs were particularly helpful, as was Richard Bak’s history of the period, Cobb Would Have Caught It (both books cited below in source notes).

Notes

1 Rud Rennie, “Baker Says Tigers Must Get Good Pitching to Defeat Reds,” New York World-Telegram, Sept. 29, 1940.

2 The Old Scout; unidentified clipping, National Baseball Hall of Fame Baseball Library.

3 Elden Auker with Tom Keegan, Sleeper Cars and Flannel Uniforms (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2001), 104.

4 Dick Bartell, with Norman L. Macht, Rowdy Richard (Berkeley, California: North Atlantic Books, 1987), 273.

5 Joe Williams, “Detroit Manager Admits He’s Just Another Guy,” New York World-Telegram, March 28, 1941.

6 Hank Greenberg and Ira Berkow, Hank Greenberg: The Story of My Life (New York: Times Books, 1989), p. 128-130.

7 Bartell, with Macht, 260-261.

8 Richard, Bak, Cobb Would Have Caught It (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1991), 277.

9 Bak, 277.

10 “Meet the Missus,” December 5, 1940, otherwise unidentified clipping, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

11 Brent Kelley, The Pastime in Turbulence: Interviews With Baseball Players of the 1940s (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2001), 45.

12 Frederick G. Lieb, The Detroit Tigers (New York: G.P. Putman’s Sons, 1946), 248.

13 Lieb, 254.

14 Ted Williams, as told to John Underwood, My Turn at Bat: The Story of My Life (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1969), 264-265.

15 Don Larsen, with Mark Shaw, The Perfect Yankee: The Incredible Story of the Greatest Miracle in Baseball History (Champaign, Illinois: Sagamore Publishing, 2001), 95.

Full Name

Delmer David Baker

Born

May 3, 1892 at Sherwood, OR (USA)

Died

September 11, 1973 at Olmos Park, TX (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.