Fred Taylor

In 1956, the fall of my freshman year at Ohio State, I went out for the frosh basketball team. (Freshmen then were still not eligible for varsity sports at major colleges.) I had no great expectations considering my modest portfolio of high school hoops exploits. My primary motivation was to meet the head freshman coach, Fred Taylor, who was also the head freshman baseball coach, the sport where I felt I had a real chance to make the team.

In 1956, the fall of my freshman year at Ohio State, I went out for the frosh basketball team. (Freshmen then were still not eligible for varsity sports at major colleges.) I had no great expectations considering my modest portfolio of high school hoops exploits. My primary motivation was to meet the head freshman coach, Fred Taylor, who was also the head freshman baseball coach, the sport where I felt I had a real chance to make the team.

The first day of basketball tryouts began with 22 players on scholarship or partial scholarship, plus me and some 60 other walk-ons. Taylor met with the walk-ons as a group just long enough to shake our hands one by one as he asked us our names before swiftly turning us over to one of his graduate assistants, Robin Freeman, so he could work exclusively with the scholarship players while we practiced in a separate gym.

It was my lone contact that fall with the first ex-major league ball player for whom I had aspirations of one day playing. Not nearly enough for me to get any real sense of the man who in later years would epitomize the transition from major-sports coaches at Division I colleges, who not only preached but put into practice the philosophy that receiving an education must be on an equal par with being a member of a winning team, to today’s major-sports coaches at almost all Division I schools who are here today and gone tomorrow, often accompanied by multi-million dollar buyout packages, unless they are willing and able to win at virtually any cost.

For several weeks I practiced with the walk-ons under Freeman, who a year earlier had become Ohio State’s first repeat All-American and the first player in the Big Ten to average 30+ points per game in back to back years before his career came to a sad halt when he severed the tips of two fingers on his shooting hand while chopping wood. For a brief time Freeman was enamored of me because his forte–long range jump shots, worth only two points in those days–happened also to be mine. But whereas Freeman had been the complete package as a player he soon realized that I had no other distinguishing skills. Still, I continued to don my practice duds every afternoon if only because I feared Taylor might frown on my quitting, although I had no reason to believe he even knew who I was. One day, when I chanced to pass his office as he was emerging from it, I marshaled the nerve to ask him when freshman baseball tryouts would begin. He told me—the first day of spring quarter—and then, after I thanked him and started to walk away, he asked me what position I played. When I said first base, Taylor said, “Great! There’ll be a spot for you if you can go as deep with your bat as you can with your shooting arm.” I was stunned. To my knowledge, I’d never been observed by him in action for a single second on the basketball floor, yet he somehow not only knew who I was but where my one true skill in the sport lay!

Freshman baseball tryouts under Taylor provided further revelations. I was accustomed to high school football coaches to whom coaching baseball was a task they took on mostly for the extra money. Their contributions were to dump a bag of balls on the field prior to practice, fungo a ball or two and then retire to the bench. But Taylor wasn’t just a presiding presence—he was the first baseball coach I ever had who could actually teach the nuances of the game. What’s more, because baseball at OSU lacked the cachet of basketball, let alone football, he had no one like Freeman to assist him and thus was both the captain and crew of the frosh diamond ship.

Owing to raw weather, my first taste of Taylor’s baseball coaching style came on an evening in early March 1957 at the indoor varsity baseball practice field—really no more than a skin infield diamond enclosed in thick protective netting to prevent balls from sailing into the track practice area beyond it. There were close to 90 freshmen on hand for that initial tryout, only seven of whom were on scholarship or partial scholarship—further evidence of the light regard in which baseball was then held by the university athletic department. The session began with us split into small groups playing pepper while Taylor made the rounds asking all the non-scholarship players for their names and the high schools they attended. Then, due to our large number, the aspiring position players got only four batting practice swings, the pitchers each threw to at most four or five hitters and the catchers got in perhaps ten minutes apiece of work behind the plate. The evening ended with each of us circling the bases at top speed one at a time and sliding into home. While my description of the occasion may make it seem to have been tedious with a lot of standing around, it was anything but. When a beefy scholarship freshman stalked away from the plate after taking his quota of BP swings, Taylor cracked, “If those were your best cuts, son, you’d better start carrying plenty of bandages.” A towering pop fly lifted by another player later that evening was “A home run in a test tube.” When a BP ground ball hit my way at first base took a wicked hop and bounced off my chest, Taylor hollered, “Eat him up, hot grounder.” Every hard slide into home at the tail end of practice brought a raucous “Grab a root and growl!”

Taylor’s wry sense of humor and plethora of novel baseball expressions were music to my ears and made every tryout session nearly as much of a pleasure to me as his coaching methods. The daily scrimmage games he conducted once the weather allowed us to move outdoors were rife with experimentation. Catchers with mobility got plenty of innings at third base, pitchers with live bats often found themselves in center field, shortstops and second basemen switched positions every other inning. I was among the few that never saw action anywhere but at first base, and that worried me. Contrary to basketball, where he’d had not only Freeman but several other graduate assistants under him, Taylor couldn’t effectively coach an unlimited number of neophytes by himself. During the second week of tryouts he announced that the squad would be pared to 25 by the following Friday. Even though I felt I deserved to make the team, I was apprehensive about my chances because there were no fewer than eight other candidates for first base. Should I tell Taylor I’d caught one summer in American Legion ball? Should I scare up the bravado and say I’d pitched a couple of innings in high school?

My fears were for naught. On cut-down Friday my name was among the select list of 25 he posted on a bulletin board outside his office. But the following Monday Taylor watched me intently during infield practice. After my tour at first base ended he asked to see my mitt. It was a Trapper model that had seen better days. “You need another glove,” he told me, “one that’ll give you a better feel for the ball.” I knew what he meant; with my floppy elongated Trapper model I often had to glance into it to make doubly sure I’d snagged a throw. Taylor then offered a suggestion. He’d used a smaller-sized Ferris Fain model himself in his playing days and had an extra one in good condition that he could sell me. “How does ten dollars sound?” he said.

Like Rachmaninoff. I’d gladly have paid twenty times that for a mitt devised by Fain, probably the best-fielding first sacker in the game before suffering a crippling knee injury in 1954, much less one used by an ex-big leaguer who was the best baseball coach I ever had. I still have it.

Frederick Rankin Taylor was born on December 3, 1924, in Zanesville, Ohio, the first child of John Frederick Taylor, known as Big Fred, and Blanche Rankin Taylor. Big Fred was a lifelong resident of Zanesville and was born there on March 18, 1888. Taylor’s mother was born in West Bloomfield, Ohio, on May 6, 1892, but was living in New Concord, Ohio, when the pair married on October, 24, 1923, and then took up residence in Zanesville, where Big Fred was employed as a railroad fireman. He later worked as a furniture salesman at Quality Furniture and finished his career at Atlas Hazel Glass before retiring in 1955. Some three years after young Fred’s arrival his lone sibling, a sister Mary Bernice (Mary Bee), was born on August 26, 1927.

Taylor entered Zanesville High School, then known as Lash High, as a 14-year-old sophomore in 1938. Tall for his age—he was 6’1”—but a proverbial beanpole, he tried out for the basketball team but was among coach Bill Zink’s early cuts. That same year Taylor began dating his future wife, Charlotte Eileen Stillion, a native of Struthers, Ohio, whom he had first met in junior high school and always called Eileen. By Taylor’s senior year the pair were “pretty serious,” according to his daughter Janna Taylor Roewer, but he had yet to make the varsity basketball team. After he’d been cut for the third successive year by Zink, a player was kicked off the team and Taylor was added to the squad as its 10th man, although he didn’t play enough to letter. Indeed Taylor finished his high school career without having earned a single varsity letter. Although the school had a baseball team, it was coached by John Brammer, Zink’s basketball assistant, and Taylor may have had a prickly relationship with Brammer since he preferred to play instead for an AAU team called the Hoffman Roofers throughout his high school years.

In the fall of 1942 Taylor enrolled at Ohio State and tried out for the freshman basketball team. To his joy (and no doubt Zink’s utter dismay) he made the club, but his varsity ambitions were put on hold when he was drafted into the Army upon turning 18. Soon after entering the service he successfully applied to be transferred to the Air Corps. During training at Oswego, New York, his aspirations to become a pilot were dashed when he learned his vision was not good enough. He ended up going to gunnery school and was part of the ground crew for military aircraft support, first at Lowry Field in Colorado and then in Alexandria, Louisiana. By the time Taylor reached his final military assignment he had grown to his full height of 6’4”, put on weight and matured enough as an athlete that he was not only able to hold his own against both college and professional players but became a player-coach for both the baseball and basketball teams in Alexandria before he mustered out of the service in 1946. His crowning achievement came in the Second Air Force championship basketball game, when he scored 24 points against the postwar Harlem Globetrotters star center, Goose Tatum, but unfortunately Tatum tallied 28 and his team won by a basket.

Once back in civvies, Taylor returned to Ohio State under the GI Bill and majored in physical education. In 1947, his first year of varsity eligibility, he made both the basketball and baseball squads and also married his high school sweetheart, Eileen. On the court he served as a backup center to future NBA Hall of Famer Neil Johnston and his powerful lefty swing enabled him to capture the first base post on the diamond. By his senior year Taylor took a back seat for the honor of being the Buckeyes’ top all-around athlete only to the future Heisman Trophy winner, tailback Vic Janowicz, who also caught for the baseball team, and Dick Schnittker, an All-American forward and an end on the 1950 OSU Rose Bowl champs. In the 1949-50 basketball season Taylor joined with Bob Burkholder and Schnittker to lead OSU to the Big Ten title under coach Tippy Dye and a trip to the NCAA tournament, where the Bucks lost in the quarterfinals by a single point, 56-55, to the fabled CCNY team that copped both the NIT and the NCAA trophies in March 1950. (The CCNY team self-destructed the following year when several of its stars were caught in the infamous point-shaving scandal that rocked the college basketball scene in the early 1950s.) Later that spring, after hitting .351, Taylor became Ohio State’s first baseball All-American as part of a lineup of honorees that also included two other future major leaguers, pitcher Murray Wall and outfielder Bob Cerv.

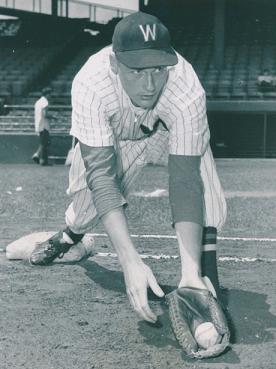

After his lengthy armed services interruption Taylor was 25 going on 26 as his college graduation approached. Feeling he was too old to launch a career in professional sports, he aspired to become a high school basketball coach. He was disappointed when the position at Upper Arlington, a suburb of Columbus, went to someone else, but after a fruitful interview with the superintendent of schools in Lima he was promised the job, pending board approval. Instead a few days later a penny postcard arrived in the mail, saying that the board wanted someone with experience for the Lima Central position. Left at loose ends, Taylor belatedly accepted the $5,000 bonus Washington had offered him in the spring of 1950 and was sent immediately to its top farm club, Chattanooga of the Class AA Southern Association. The Senators at the time were so bereft that they were the only major league club without a Triple-A affiliate.

Taylor showed enough potential in his half season with Chattanooga to be called up in September 1950 by the parent club. In his debut on September 12 as a pinch hitter for pitcher Mickey Harris, he grounded out in the ninth inning of a 3-2 loss to the Tigers’ Dizzy Trout. With another Mickey– two-time American League batting champion Mickey Vernon– a fixture in Washington at first base, Taylor appeared in only five more games that month and then was farmed again in 1951 to Chattanooga. Playing for a last-place team in a pitchers’ park, he hit a respectable .291 and contributed eight of the club’s 45 total homers, earning another late-season recall. Although he batted just .167 in 12 at-bats, his career highlight came on September 18 in the second game of a home twi-night doubleheader against St. Louis. In the ninth inning of a 3-2 loss to the Browns’ ace, Ned Garver, Taylor rifled a shot to deep right field in Washington’s cavernous Griffith Stadium. Recalling the event in 1957 after a member of my freshman team asked him if he’d ever homered in the majors, Taylor said no but then laughed. “I was so sure one ball I hit was out that I went into my Cadillac Trot as soon it left the bat and then had to turn on the juice just to make second base after it hit the wall.” Taylor’s only other extra base hit in the majors, another double, came in 1953 when, for the third successive year, he was called up in September after the Senators loaned him to White Sox’ and Athletics’ Triple-A affiliates in Toledo and Charleston, respectively, and he struggled to hit a combined .227 with just a .299 slugging average. Still blocked by Vernon, he was released after the season ended despite his best showing in Senators’ garb that September–.263 in 19 at-bats. Taylor signed with unaffiliated Beaumont of the Double-A Texas League for 1954. Finally playing in a friendly hitters’ park, he hammered 22 homers, second on the club only to Les Fleming’s 27, but his .252 mark scarcely matched the team batting average, pitchers included.

By that time Taylor was nearing his 30th birthday and had reached the end of the four years he had given himself to make the majors. But he had cushioned himself for his departure from pro baseball by becoming a volunteer basketball assistant at OSU in 1951 under coach Floyd Stahl, which turned into a full-time position as the school’s first head freshman basketball and baseball coach in 1953. As Stahl’s chief co-recruiter, Taylor played a pivotal role in bringing the first two African American players in OSU history to the school’s basketball program in 1952 in addition to future All-American Robin Freeman. The African American pair were guard Ray Tomlin from Cincinnati Lockland Wayne, then an all-black school, and Cleo Vaughn, an All-State forward from Lima Central, ironically the school where Taylor had been all but promised he would be hired to coach two years earlier.

But Tomlin transferred to Xavier after his freshman year, eventually joined the Army, and then bounced around until he was 72 before at long last obtaining his college diploma, and Vaughn left the team following his junior season after encountering one too many incidents of racial prejudice when the Buckeyes took to the road. It remained for Joe Roberts, one of the 22 scholarship players on my freshman team to stay the course, to become the Bucks’ first impact African American cage star. Roberts and Dick Furry were the only two members of the 1956-57 frosh squad to help form the core of the first varsity club Taylor put on the floor after he replaced Stahl as OSU’s head basketball coach in June 1958. Taylor’s first order of business after assuming Stahl’s job was to personally paint a scarlet block “O” on the midcourt stripe of St. John Arena (Buckeye Sports Bulletin, January 12, 2002). His second mission was to immediately put into practice the lessons he had learned as a freshman team coach. Based in part upon his experience with his 1956-57 scholarship recruits, more than half of whom were no longer on the squad after the fall quarter ended, Taylor had by then solidified his thinking that academic achievement was as significant as athletic accomplishment and begun to recruit accordingly, offering scholarships only to high school seniors he felt secure would not only avoid eligibility problems but also give meaning to the term “student-athlete.” Led by junior forwards Roberts and Furry and senior center Larry Huston, the 1958-59 Ohio State cagers finished just 11-11 on the court but posted a 3.13 grade point average, well above the school’s undergraduate average of 2.60. (By the time Taylor left his OSU coaching station a phenomenal 97 of the 102 lettermen under his guidance had gone on to graduate.)

Waiting in the wings, meanwhile, was the first freshmen class for which Taylor had been the primary recruiter. Its ranks numbered five players—all from Ohio—who would play a key part in Ohio State’s unparalleled success up to that point in the history of the college hoops ranks. Nationally-recognized center Jerry Lucas of Middletown was the crown jewel, surrounded by four other diamonds in the making: Mel Nowell of Columbus, Gary Gearhardt of New Lebanon, Bobby Knight of Orrville, and last, but far from least, John Havlicek of Lansing. The quintet would meld with Roberts, Furry, and junior guard Larry Siegfried to help bring OSU the first three of a record string of five consecutive Big Ten championships and, in time, would become part of the only club ever to spawn four future college and/or pro Hall of Famers—Lucas and Havlicek as players and Taylor and Knight as coaches. With three sophomore starters in 1959-60, plus Roberts and Siegfried, Taylor marched the Buckeyes to their lone NCAA championship to date. The club was so dominant that in the NCAA tourney it won each of its games by at least 17 points and in the final dismantled the favored defending champion California Bears 75-55 after leading by 20 points at halftime. Over the three-year period that Taylor richly enjoyed the fruits of the first freshmen class he recruited upon assuming the head coaching job, Ohio State went 78-6. Unfortunately two of the losses came to Cincinnati in the 1961 and 1962 NCAA finals. In 1961 the Bucks appeared to take the Bearcats too lightly and lost in overtime. Not about to make the same mistake again, they nevertheless fell to a repeat Cincinnati champion the following year when Lucas severely injured his knee in the semi-final win over Wake Forest and hobbled gamely but ineffectually on a heavily bandaged leg throughout the final.

After the Lucas-Havlicek-Nowell era ended, Ohio State won back-to-back Big Ten co-championships in 1962-63 and 1963-64 sparked by Lucas’s replacement at center, Gary Bradds, but was denied an NCAA bid in either season because only the conference champion at that time was invited to the NCAA tourney and, in the event of a co-champion, the invitation in the Big Ten went to the team that had gone the longest since its last NCAA appearance. In the latter year, 1964, basketball historians have since noted that the college game quickly began to change radically when UCLA won the first of its 10 NCAA titles in 12 years under coach John Wooden, most with such ease that rival schools and coaches were driven to lower their academic standards along with almost every other boundary in order to scrape together enough talent to remain even mildly competitive with the Bruins.

I last saw Taylor outside the home team locker room in St. John Arena on the final evening of the 1964-65 season shortly after OSU, a huge underdog lugging just a 5-8 record in Big Ten play, had dealt Michigan and All-American Cazzie Russell, their lone conference loss of the campaign, enabling the Bucks to lift their own overall season record to an even .500. Amid a milling congratulatory crowd we had an opportunity to speak only briefly. It was my first face-to-face meeting with him since the fall of 1958 when I had been Ohio State’s Rhodes Scholarship nominee and had asked him to be one of the three faculty members I needed to provide me with recommendations. His excitement over my selection and enthusiasm to comply with my request, along with a couple of personal setbacks around that time that forced me to drop out of school for a while, stopped me from ever telling him that I never made it past the initial Rhodes screening process. I was still too mortified to bring up the incident and thank him again not only for the recommendation but for his support throughout my early years at OSU, but in the few minutes we spoke he brought it up himself and said that regardless of the outcome it had been a proud occasion for him and an honor to have been asked for his assistance. It pleased him all the more when he learned I was in graduate school at the time.

Soon after that I moved to New York but continued to follow all of my alma mater’s sports teams. I was in a crowded smoky bar in the West Village glued to its black and white TV set the night in 1968 that the Bucks, in Los Angeles for their last Final Four appearance under Taylor, lost to North Carolina in the semis after bringing him his sixth Big Ten title in a most improbable fashion. After completing their conference season with a 10-4 record on March 4, demoralized Buckeye players held their banquet the following night and turned in their uniforms. Four nights later, on March 8, they dialed in their radios to—horror of horrors–root for none other than Michigan. The Wolverines, 5-8 in the conference, needed to beat 10-3 Iowa to drop the Hawkeyes into a first-place tie with the Buckeyes. Taylor told the Cleveland Plain Dealer before the game that the chances of a Michigan win were “slim and none.” But when the Hawkeyes missed a shot at the buzzer, the Wolverines triumphed 71-70. Ohio State players stampeded to reclaim their uniforms the following morning and jubilantly traveled to the Purdue campus in West Lafayette, Indiana, a neutral site, for the first Big Ten playoff game since Chicago beat Wisconsin, 18-16, for the 1908 league title. This contest was in the making only because conference officials had passed a rule in May 1967 creating the modern day tiebreaker. An 85-81 win at West Lafayette propelled OSU to the Mideast Regional at Lexington, Kentucky, and an eventual trip to Los Angeles when Taylor’s comeback kids edged Kentucky 82-81 on Kentucky’s home floor. The loss so enraged Wildcats coach Adolph Rupp that he ducked the postgame news conference, prompting Buckeye guard Bruce Schnabel to gleefully dash off a poem: “Some say we were good, some say we were lucky, all I know is we’re in L.A. and Rupp is still in Kentucky.” (Lee Caryer, The Golden Age of Ohio State Basketball 1960-1971)

Taylor’s seventh and last Big Ten championship came three years later when center Luke Witte and guards Jim Cleamons and Alan Hornyak spearheaded the Buckeyes to a 13-1 conference record, but OSU, after leading Western Kentucky for most of the game in the Mideast Regional final, lost 81-78 in overtime. With most of his core players returning, Taylor looked forward to another championship run the following season. About to occur was the stormiest incident of his coaching career and one that will forever scar college basketball. On the night of January 25, 1972, the Bucks and the Minnesota Gophers, both undefeated in conference play, met in Minnesota. Ohio State led 50-44 with 36 seconds left when Buckeye center Luke Witte was flagrantly fouled by Minnesota’s Clyde Turner as he was about to score an easy layup that would ice the game. Turner was ejected on the spot as Witte lay stunned under the basket. Minnesota’s Corky Taylor extended a hand to Witte as if to help him to his feet but then kneed him in the groin as he was rising. “A melee ensued,” according to The Ohio State Lantern, “with players and fans alike” charging onto the court and forcing OSU players to flee for cover. “As Witte attempted to get up once more,” Minnesota’s Ron Behagen, “who had fouled out earlier in the game, kicked him in the head until he was unconscious.” Meanwhile OSU forward Mark Wagar was seized by the Gophers’ Dave Winfield, now enshrined in Cooperstown, and Winfield punched him senseless as his arms were held pinned to his body by Minnesota fans.

Sports Illustrated recounts:

The final 36 seconds were not played, for fear that the Gophers and their fans would rage out of control {and the game was forfeited to OSU}. Later, when {ex-major league pitcher} Paul Giel, Minnesota’s new athletic director, visited the Ohio State locker room, he found Fred Taylor, the Buckeyes’ coach, pale and quivering with rage and indignation. “I knew it would be emotional,” said Giel, apologetically, “but I had no idea it would be like this.”

“It was bush,” answered Taylor. “I’ve never seen anything like it. But what do you expect from a bush outfit?”

Although the Gophers and their new head coach Bill Musselman were the objects of scorn from the fans of every other school in the Big Ten after the debacle, they escaped with a modest penalty when Big Ten Commissioner Wayne Duke suspended Corky Taylor and Behagen for the rest of the season while allowing Winfield, Musselman and the remainder of the Minnesota team to go unpunished.

Fred Taylor’s relationship with his alma mater and especially with Athletic Director Ed Weaver began to deteriorate after the incident. He felt OSU should not have accepted the minimal penalties handed down by Duke. “I think we sold our kids down the river by not forcing the issue on penalties or anything else,” Taylor told the Lantern (March 6, 1987). “The administration…treated it as just another basketball game. That certainly couldn’t have been further from the truth…I have to say my relationship with Ohio State went downhill after that date.” In later years Taylor went even further, saying that he should have quit then and there after he received so little support from his superiors for his hard-hitting stance on the issue.

After losing the Big Ten title to Minnesota by one game in 1971-72, OSU slipped to an 8-6 conference mark the following year while Taylor struggled with health issues that finally were resolved by surgery for a hiatal hernia. In late March 1973 he appeared to be headed to Northwestern when his old OSU coach Tippy Dye, who was now the Wildcats’ Athletic Director, offered him a significant raise in salary and a multi-year contract to succeed coach Brad Snyder, who had resigned earlier in the month. Taylor was making only $22,000 at OSU at the time and, like all Buckeye athletic coaches in that era including Woody Hayes, although given frequent verbal assurances that his job was secure, he never received more in writing than a one-year contract. In the end he remained at OSU when Weaver hiked his salary to $32,000, the top figure he would ever make as coach of the Scarlet and Gray.

Weaver in retrospect lived to regret his decision to retain Taylor, but Taylor never regretted turning down the Northwestern offer. Ohio State was too deeply in his blood for him to leave it for a job elsewhere. In 1987 he told the Lantern he just wanted to be remembered as a coach who truly loved his work situation. “I didn’t coach for recognition. I coached because it was something I’d dreamed of doing at my alma mater. It wasn’t a job, it was just something I wanted to do.”

Taylor’s last three years of coaching were marred by frequent clashes with Weaver. Weaver at one point refused to hire Dave Merchant as an assistant, at Taylor’s request, to help with recruiting, and then grumbled on TV that the reason Taylor’s teams were no longer consistent winners was “because recruiting was down.” Taylor was accused explicitly of being overly obsessed with his concept of the student-athlete, and some even hinted that he had developed a bias against bringing black players into the OSU program since the Buckeyes had fewer blacks on their teams in Taylor’s later years than they’d had earlier in his career. But Lee Caryer, the author of The integration of Ohio State Basketball, proved there was no truth to the assertion in his newspaper series on the integration of men’s basketball at Ohio State. Caryer first reminded readers that Taylor had been instrumental in recruiting the first blacks to play for OSU and then confounded Taylor’s critics who claimed he made preconceived judgments about potential recruits:

However, he absolutely made judgments … Does the young man have the athletic ability to compete?…Will he be a good teammate? A credit to the university? … Is he prepared, academically? Can we prepare him through tutoring assistance? Will he work, on the court and in the classroom?

Taylor judged every one of those qualities, and considered academic achievement far more important than some of his coaching peers. If he judged a high school player to be able to excel both on the court and in the classroom, he recruited him.

When he did, Taylor made the same promise to each recruit, “You will get a good education and we will compete for the Big Ten championship.” However, Taylor did not pre-judge, or the athlete would not have been offered an Ohio State scholarship, nor would Buckeyes like Joe Roberts, David Barker, Mel Nowell, Jim Doughty, Tom Bowman, Jim Cleamons and Larry Bolden, African-American basketball players who found greatness as students, players and men at Ohio State under Fred Taylor, speak of him as they do today.

Caryer’s admiration for Taylor’s coaching and recruiting methods notwithstanding, the feud between Taylor and Weaver came to a head in the spring of 1975 when, as Taylor later told Columbus Dispatch reporter Ron Emler (February 9, 1976), “I had a conversation with the athletic director. He said to win or else. I asked him to explain, and he said it’s just what it sounds like.” The following February, with the season still underway, rather than tolerate any more of Weaver’s dictates, Taylor personally handed his letter of resignation as OSU’s men’s basketball coach to University President Harold Enarson, deliberately bypassing Weaver in the chain of command. His only stipulation was that he could tell his current squad of his resignation before anyone else learned of it so that they would not think he’d left because they hadn’t won for him. He later offered a fuller explanation to Kaye Kessler of the Columbus Dispatch (February 6, 1986): “I’m really a sensitive guy [despite his crusty exterior]—the situation just reached a point where I knew it wouldn’t get any better. I’ve made my overtures to change things with our basketball program directly to the athletic department and it hasn’t done any good.” To Dick Fenlon of the same paper (May 6, 1986) he said: “My dad told me years and years ago that if you can’t respect someone, you can’t work for them…What bothered me most was it was my alma mater. I felt that my alma mater shouldn’t have allowed all the things to happen that did happen.”

Taylor stepped down at the close of the 1976 season, his 18th as the head men’s basketball coach at OSU, leaving behind a remarkable legacy: a 297-158 career record, including an incredible 50 straight wins at home—a streak that ran from December 1, 1959, the opening game of that season against Wake Forest, until December 11, 1963, when the Buckeyes fell to Davidson—a record .750 winning percentage in the first 100 games he coached against Big Ten Conference foes and back-to-back UPI College Coach of the Year awards in 1961 and 1962. (Columbus Dispatch, January 8, 2002)

Yet, while he had quit his coaching post on his own terms, he still could not walk away from his alma mater entirely. He maintained a position with OSU’s physical education and intramural department for two and a half years so that he could complete the requisite 25 years of service to the university that enabled him to receive full medical retirement benefits. Taylor’s daughter Janna described his last days at OSU as “Not a happy time for him at all—he liked being with the kids, but it was very difficult for him to be there. Dad had an artistic side, and Mom signed him up for watercolor painting lessons. He really did enjoy that and painted many beautiful paintings, which helped him relax.”

Still only in his mid-fifties, in addition to painting Taylor remained active on the basketball scene, working as an NBC commentator for a time and serving as an assistant coach on the U.S. team that won the gold medal in the 1979 Pan American Games. That same year he industriously took up another sport that had previously been only an occasional pastime when he became manager of The Golf Club of New Albany, Ohio, a job that lasted until 1996. According to Janna, “He loved being at The Golf Club! He (played) golf, but being the athlete and competitor he was, was never happy with his game. My husband thinks Dad was probably in the 6-10 handicap range.”

In 1987 Taylor was inducted into the National Basketball Coaches Hall of Fame. The following April, at what had been planned as his roast, he was toasted instead by many of his former players, with Bobby Knight fighting emotions as he presented Taylor with a sport coat as a gift from the many players he had coached in his 18 years on the Buckeyes’ bench. Taylor and the notoriously hot-tempered Knight, who had formed a special bond even while Knight was still an OSU player, took turns tossing humorous jabs at each other. Taylor hooted: “Bobby Knight in a tuxedo. That’s the second time in 30 years he did anything I wanted him to do. The first was taking the Army coaching job.” And Knight fired back: “I remember him saying after a bad call, ‘If this bench was a chair, I’d throw it out there.’ I never forgot that. I knew there would be a time when it would come in handy.” (Columbus Dispatch, April 26, 1988)

But Taylor’s proudest post-coaching occasions came at the 25th and 35th reunions of his 1960 national champions in 1985 and 1995, respectively. At the 25th reunion on October 18, 1985, Taylor related that the thing that stuck uppermost in his mind was that each of the freshmen—Knight, Jerry Lucas, Mel Nowell, Gary Gearhardt, and John Havlicek, the original “Fab Five”—had been his team’s leading scorer in high school. “Havlicek,” Taylor said, “was the one perceptive enough to see a problem. So he told me he would make the team at the other end of the court—as a defender.” That defender not only replaced co-captain Dick Furry as a starter in the first half of the “Fab Five’s” first game against Wake Forest but remains the Boston Celtics’ all-time leading scorer with 26,395 points.

Little more than a year after the 35th reunion, on April, 30, 1996, Taylor underwent surgery for a brain aneurysm. Not long afterward he suffered a heart attack and spent most of the remaining years before his death on January 6, 2002, in convalescent centers and nursing homes. Among his surviving family members were his wife of 54 years, Eileen, his four daughters—Janna Roewer, Krista Zimmerman, Nicola “Nikki” Kelley and Sharla “Shar” Peponis—and 12 grandchildren ranging in age from 36 to 16 as of December 2012. It was his grandchildren who, in Taylor’s wheelchair presence, unveiled the street sign on the OSU campus in November 1998 that renamed a section of Fyffe Drive near the Schottenstein Center Fred Taylor Drive.

Many of Taylor’s former players attended the various memorial events after his passing, and almost all of them spoke. Bill Hosket, an All-Big Ten center on Taylor’s last Final Four team in 1968, after adding his voice to those who affirmed that much of their success in life could be directly attributed to their college coach, said, “I think his legacy is honesty and integrity and just examples of what his former players and family members can carry forward. I don’t think there is anyone in college basketball who was respected more than Fred Taylor.”

Of humble roots, Taylor might never have risen to heights he could not have imagined for himself after he was cut from his high school basketball team for the third straight year if destiny had not twice intervened in ways that at the time they occurred must have seemed like setbacks to him. Removed from college by the draft when he turned 18, by the time Taylor returned to OSU he was 22 and his athletic skills were fully developed. Upon graduation, he might have been content coaching high school baseball (Baseball was his favorite sport and he continued to play in recreational leagues until he was in his forties.), but no high school physical education programs in Ohio at that time hired someone simply to coach baseball, which was considered a minor sport. So he tried for series of high school basketball coaching jobs and then turned to pro baseball when he failed to land any of them. Playing pro ball granted him enough financial freedom to become an unpaid basketball assistant at his alma mater, a stepping-stone that led to his becoming OSU’s first ever head freshman basketball and baseball coach. When varsity basketball coach Floyd Stahl opted after the 1957-58 season to give up the travails of coaching to become OSU’s assistant athletic director, Taylor was the natural choice to replace him at a school that in his era still believed in promoting from within.

This chain of events produced, in Bobby Knight’s estimation, “the singularly most influential person on Big Ten basketball by far.”(Lantern, March 6, 1987) Upon learning of Taylor’s death hours after his Texas Tech team beat Kansas State, Knight expanded on his feelings about his former coach and mentor. “Fred Taylor was an absolute giant in coaching. You could have in no way played for a better coach in college from whom you learned more and in no way could have had a better friend. What’s my team? My team is an extension of his team.”

Last revised: January 8, 2023 (zp)

Sources

Blaine Bierley, Ohio State sports historian

Buckeye Sports Bulletin

Lee Caryer, The Golden Age of Ohio State Basketball 1960-1971 Companion Press, 1991

Caryer, The Integration of Ohio State Basketball

Columbus Dispatch

Columbus Citizen-Journal

Nikki Taylor Kelley

Janna Taylor Roewer

Sports Illustrated

Eileen Taylor

The Ohio State Lantern

The Ohio State University Archives

The Ohio State University Football Program, November 7, 1959

Full Name

Frederick Rankin Taylor

Born

December 3, 1924 at Zanesville, OH (USA)

Died

January 6, 2002 at Columbus, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.