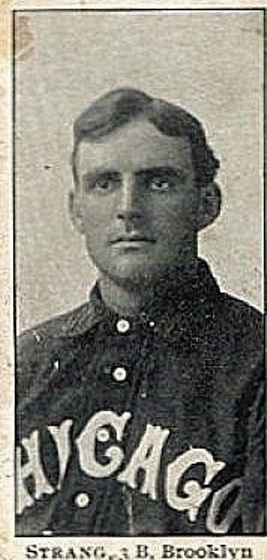

Sammy Strang

Before the 1915 Army-Navy baseball game, 24-year-old Dwight “Ike” Eisenhower led his fellow Army cadets in the “Long Corps” yell: “Rah, Rah, Ray! Rah, Rah, Ray! West Point, West Point, AR-MAY!”1 Playing left field for the Army team was 22-year-old Omar Bradley. By a score of 6-5, Army defeated Navy for the seventh consecutive year under Sammy Strang, the most successful coach in the US Military Academy’s baseball history.

Before the 1915 Army-Navy baseball game, 24-year-old Dwight “Ike” Eisenhower led his fellow Army cadets in the “Long Corps” yell: “Rah, Rah, Ray! Rah, Rah, Ray! West Point, West Point, AR-MAY!”1 Playing left field for the Army team was 22-year-old Omar Bradley. By a score of 6-5, Army defeated Navy for the seventh consecutive year under Sammy Strang, the most successful coach in the US Military Academy’s baseball history.

Strang was a college-educated Renaissance man who defied his upper-class upbringing by playing professional baseball at the turn of the 20th century. He was speedy and versatile, and he could hit. Honus Wagner selected him as a pinch-hitter on his all-time all-star team.2 Strang was one of the most colorful New York Giants in the team’s history.3

Samuel Strang Nicklin was born on December 16, 1876, in Chattanooga, Tennessee. He was known as Strang Nicklin in Chattanooga. He was the third of four sons born to John Bailey Nicklin (1843-1919) and Elizabeth “Lizzie” Kaylor Nicklin (1850-1925). The Nicklins were a prominent and wealthy family in Chattanooga. John owned a drugstore and was a banker, and he was mayor of Chattanooga from 1887 to 1889.4 He was “untiring in his efforts” to promote baseball in the South5 and served as president of the Southern League from 1893 to 1895 and in 1901-02.6

Young Strang was popular with his classmates, but to his teachers he was a “terror.” Once, after being sent out of the classroom for misbehavior, he climbed onto the roof of the school and made faces through the windows of the top floor, disrupting several classes.7 Strang loved baseball. As a teenager he played on top amateur teams in Chattanooga.8 His performance as a 17-year-old was noted in Sporting Life in 1894: “He hit the ball hard every time he came to bat,” and he can “turn and sprint to the fence and nab a long fly with the grace of a [Jimmy] McAleer,”9 the great outfielder of the Cleveland Spiders. In the spring of 1895 the Cincinnati Reds stopped in Chattanooga and played an exhibition game against Strang’s team. Hall of Famer Buck Ewing, the Reds’ player-manager, crushed a ball to deep center field. The 18-year-old Strang “turned like a flash at the crack of the bat,” chased the ball down, and made a leaping catch. “The stands roared with applause and Buck Ewing got the surprise of his life.”10

In 1895 and 1896, Strang played for teams in Asheville, North Carolina; Knoxville, Tennessee; Madisonville, Kentucky; and Lynchburg, Virginia. Spotted by Phil Reccius at Madisonville,11 Strang received a 14-game tryout in 1896 as a shortstop for the last-place Louisville Colonels of the National League. At 19, he was the youngest player in the National League. He appeared in Louisville box scores as “Nicklin.” In his major-league debut, on July 10, 1896, he went 1-for-2 and scored two runs in a 10-8 victory over Philadelphia.12 Louisville second baseman Jack Crooks said Strang was the speediest shortstop he ever saw.13

Strang attended the University of North Carolina in 1895-96 and the University of Tennessee in 1896-97, and he was a star athlete at both schools. He captained the 1896 Tennessee football team, and on November 26 he scored four touchdowns in a 30-0 victory over Central University of Kentucky.14 He suffered a knee injury playing football, though, which prevented him from playing baseball in 1897.15

Strang served in the Army in 1898 during the Spanish-American War and rose to the rank of first lieutenant in the 3rd Tennessee Volunteer Infantry. His unit did not see combat. Military records indicate that Strang was 5-feet-7 and weighed 146 pounds at age 21. On official documents, he signed his name “S. Strang Nicklin.”

In 1899 Strang decided to pursue professional baseball as a career. Although his father loved the game, his parents disapproved of his decision because they felt baseball was an unrespectable career path for their college-educated son. To protect the image of the Nicklin family in Chattanooga’s upper class, Strang played minor-league baseball far from home and under pseudonyms. He was “Clyde Strang” at Cedar Rapids, Iowa, in 1899, and “Sam Strang” at Wheeling, West Virginia, in 1899, and St. Joseph, Missouri, in 1900. Upon his arrival in the major leagues in 1900, he was “Sammy Strang.”

As a shortstop at Cedar Rapids, Strang made “phenomenal plays” and “woeful blunders.”16 He played left field at Wheeling, and he “showed splendid form” at third base at St. Joseph.17 Originally a right-handed batter, he learned to bat left-handed at St. Joseph18 and became a switch-hitter. His 52 stolen bases and 103 runs scored for St. Joseph led the Western League.19 Scout Ted Sullivan recommended Strang to the Chicago Orphans of the National League (the predecessor of the Cubs), and Strang joined the Orphans in September 1900. On his first day with the team, he got seven hits in eight at-bats in a doubleheader against the New York Giants.20 He batted .284 in 27 games for the Orphans and was traded to the Giants in the offseason. Cap Anson said the Giants were getting “one of the most promising third basemen in the game.”21

Strang got off to a torrid start in 1901, and in early June he led the National League with a .420 batting average. Sportswriters called him a “phenom”22 and compared him to Willie Keeler because of his speed and the way he choked up on the bat.23 Giants pitcher Christy Mathewson was a 20-year-old rookie at the time. In a 1911 interview, Mathewson recalled his rookie season:

“Kid Nichols was working against me. We had the tightest sort of battle all the way until Strang finally came through with a long smash and pulled me through 2 to 1. That gave me my first good start. A few days later in New York, I was sent in against Boston, again with Nichols on the other end. We had another tight mix-up, but Strang for the second time came through with a long poke that saved the day. Strang looked then to be one of the coming ballplayers of the year. He did more than his share in starting me along the right road, and I don’t think I’ll ever forget it.”24

After hitting .420 in his first 27 games with the Giants, Strang averaged .247 over his next 108 games. His fielding at second base and third base was erratic. In August he was fined $50 and temporarily suspended for “poor playing.”25 Strang claimed he had not been “dissipating” (abusing alcohol) and that he was “a victim of hard luck in his playing.”26 In September he hit his first major-league home run, off Mal Eason of the Orphans. At the end of the 1901 season, Strang ranked third in the league with 40 stolen bases, but he was second in strikeouts and tied for third with 60 fielding errors.

Hall of Famer George Davis, the Giants player-manager, jumped to the Chicago White Sox in the upstart American League for the 1902 season and persuaded White Sox owner Charlie Comiskey to sign Strang.27 Comiskey had his eye on Strang in 1899 when Strang played for Cedar Rapids and Comiskey owned the St. Paul Saints.28 Strang coached the Georgia Tech baseball team in March 1902 before joining the White Sox at spring training in April. He batted .295 in 1902 as the third baseman and leadoff hitter. He was second in the league in walks, third in runs, and fourth in stolen bases – fine numbers for a leadoff man. However, he led the league in strikeouts, and his 62 errors at third base established an AL single-season record that still stands.29 Comiskey laced into Strang after one of those errors cost the White Sox a late-season victory.30 The two men came to blows, and, according to Strang, the fight “ended in a draw.”31 After the season ended, Strang was released. He played three games in October for the Orphans and then signed with the Brooklyn Superbas of the National League.

As the Brooklyn third baseman in 1903, Strang cut down on his strikeouts and errors, and he led the team with 101 runs scored. His 46 stolen bases tied Honus Wagner for third best in the league. Strang was one of the most popular players with the Brooklyn fans.32 Brooklyn manager Ned Hanlon regarded him as “one of the cleverest men” on the team.33 Strang and shortstop Bill Dahlen devised a new play. If a groundball was hit to Dahlen with a runner on second base advancing to third base, the runner would typically round third base, expecting Dahlen to throw to first base. Dahlen would instead fire the ball to third baseman Strang, who would apply the tag before the runner could return to the bag. They “pulled it off on no less a heady baserunner than [Joe] Tinker” among others.34 Strang’s fielding was still spotty, but there were highlights. In a game against the Boston Beaneaters, he made “a fine catch of a foul by [Duff] Cooley” and then “dug [Pat] Moran’s hot smash out of the mud, and with a swift pass to [second baseman Dutch] Jordan, engineered an electrical double play.”35 One of Strang’s Brooklyn teammates was Johnny Dobbs, his childhood friend from Chattanooga. Dobbs named a son Nicklin after his pal.

In September 1903 Strang was reportedly “carrying an oversupply of fat.”36 His batting average dropped 80 points, from .272 in 1903 to .192 in 1904. He missed time during the 1904 season with an illness and sore ankle and played in only 77 games. After he made four errors in a September doubleheader, Hanlon released him. It was reported that Strang had repeatedly broken team rules and that his conduct had become “the bane of Hanlon’s life.”37 John McGraw, manager of the first-place Giants, quickly claimed Strang for his 1905 team. McGraw needed to replace his utilityman, Jack Dunn, who had accepted a managerial position in the Eastern League.38

Strang was in excellent physical condition in 1905, and he promised that “laziness will not be in his lexicon.”39 At spring training the Giants were timed running from home plate to first base on a bunt. The fastest men on the team were George Browne (3.0 seconds) and Billy Gilbert (3.2 seconds). Strang and Mike Donlin tied for third at 3.4 seconds.40 Donlin was known for his blazing speed.41 For comparison, Mike Trout was timed at 3.5 seconds on a bunt single in a 2012 game.42

Strang’s speed was valuable in the outfield. “He can go as far after a fly ball as any man living,” said McGraw in April 1905.43 Strang played the outfield and second base for the Giants, and as a utilityman, he filled in at the other infield positions. Years later McGraw said that “Strang was always a good hitter and very fast,” but he needed the variety of playing different positions to stay focused. “Give him any new job and he was such a naturally good ballplayer that he would go great guns. As soon as the novelty wore off, he would get lazy.”44

McGraw also used Strang as a pinch-hitter. This was so novel at the time that McGraw needed the consent of Giants owner John T. Brush to use Strang in this way.45 The phrase “pinch-hitter” was not yet widely known, and other words were found to explain Strang’s role. He was an “emergency man” who batted for the pitcher “at a time when a real batter was needed.”46 Strang excelled in this new role. He made seven hits in his first nine times “going to bat for somebody else.”47 Soon other teams copied McGraw’s innovation and employed their own pinch-hitting specialists. Strang’s “quiet, unassuming manner” was well suited to pinch-hitting because he did not get too excited or rattled in clutch situations.48 “Nothing seemed to bother him,” said Honus Wagner.49 “Strang was devoid of nervousness,” said McGraw.50 Strang was “the first of the real pinch hitters and one of the best,” wrote Grantland Rice.51

In those days home runs were uncommon and sportswriters celebrated them as Herculean feats. In a game against the Chicago Cubs, Strang hit a home run off Bob Wicker that was described in grand fashion by the New York Sun: “Sammy dealt the oncoming leather a prodigious blow, and it soared skyward and southward, three points east, dodged the foul line by a few feet and fell in the bleachers for a home run.”52 In another game Strang accidentally homered off Brooklyn’s Harry McIntire. After the count had gone to three balls and no strikes, McGraw gave Strang the take sign, but he hit away and smacked a home run. Strang said he ignored the take sign because the baseball was battered and black, and he was trying to foul it into the stands to get a new ball into play. Instead he hit it fair for a home run.53

In late June 1905, Strang’s .352 batting average ranked third in the National League (behind only Honus Wagner and Cy Seymour), and fans wondered why he was a part-time player. However, his average slid to .259 by season end. In August it was reported that his parents “have withdrawn their objections to his playing professional ball.”54

The Giants won the pennant in 1905 and went on to defeat the Philadelphia Athletics in the World Series. Strang appeared in only one game of the Series; he pinch-hit for Joe McGinnity in Game Two and was struck out by Chief Bender. Upon receiving a full share of the winner’s purse ($1,142) for his one at-bat, Strang declared that he was the highest-paid player in baseball.55 His wit was amusing. One day Strang was asked what kind of shirt he was wearing. “It’s a Marathon,” he said. “It can be worn a week without showing signs of distress.”56

Strang was a maverick. According to McGraw, Strang originated the baserunning trick known as the “delayed steal.” When Strang was on first base, he sometimes broke for second base after a pitch was in the hands of the catcher. “The play confuses the catcher as well as the infielders, and in many cases, neither the second baseman nor the shortstop will cover the bag,” said McGraw.57

On August 6, 1906, Umpire Jim Johnstone ejected McGraw from a home game against the visiting Cubs. The next day the irate McGraw instructed stadium personnel to deny Johnstone entry to the stadium. The impish Strang stepped onto the field and declared himself the substitute umpire. The Cubs refused to take the field, so Strang announced “in a melodramatic manner” that the game was forfeited to the Giants.58 Outside the stadium, Johnstone declared the game forfeited to the Cubs. NL President Harry Pulliam, of course, sided with Johnstone. In a letter to Pulliam, Strang implausibly argued that he had acted within baseball rules. Pulliam responded by scolding Strang for his impertinence. “I am at a loss to understand how you, being a member of the New York club, should address such a communication to me,” wrote Pulliam.59

Strang had his best season in 1906. His .319 batting average ranked fourth in the NL, and his .423 on-base percentage led the major leagues. He hit four home runs, including a grand slam off Tully Sparks of the Philadelphia Phillies. The next year Strang hit four more homers, including a pinch-hit home run off Art Fromme of the St. Louis Cardinals. Strang’s batting average dropped to .252 in 1907, but his ability to draw walks produced a .388 on-base percentage, which was fourth best in the league. In 1907 Strang was reportedly the most popular player with Giants fans.60 On June 22, 1907, the Giants nipped the Boston Doves by a score of 11-10. In the 12th inning with two outs and a man on, Boston’s Ginger Beaumont “let fly with a mighty drive” to center field. Strang “chased out with the crack of the bat” and made a leaping catch of the “screamer” to save the day.61

Outside of baseball, Strang’s greatest passion was singing.62 He was a “grand and golden baritone” whose voice was “rich, full, vibrating, sympathetic, touching the heart strings.”63 He sang popular songs of the day as well as his own musical compositions. Strang’s childhood friend Oscar Seagle was a world-renowned baritone. At Seagle’s urging, Strang made several trips to Paris to receive vocal lessons from Seagle and Seagle’s teacher, Jean de Reszke, the most famous male opera star of the late 19th century. Strang worked hard to cultivate his voice, and he sang at every opportunity. He performed in formal appearances on stage. Informally, he entertained his teammates on long train rides and cheered his team in song at the ballpark.

Strang’s interests were wide ranging. He wrote a humor column for his father’s Chattanooga newspaper. He enjoyed fox hunting in Tennessee, and he was an expert trap shooter.64 He indulged his fascination with the new “automobiles” by working one offseason as a chauffeur.65 Strang was so intrigued by aviation that he rented a workshop in Harlem in which he attempted to build an airship. He said the project was going all right except for two problems: getting his contraption into the air and making it stay there.66

In the spring of 1908 Strang requested that henceforth he be called by his real name, Strang Nicklin. He was so well known as Sammy Strang, though, that his request led to confusion. He appeared in newspapers that year as Sammy Strang, Sammy Nicklin, Sammy Strang Nicklin, Sammy Strang-Nicklin (hyphenated), and even Sammy Strang Michlin (misspelled). He got off to a slow start with only five hits in his first 53 at-bats (an .094 average), yet he drew 23 walks and his on-base percentage was a robust .385. An impatient McGraw sold him in early June to the Baltimore Orioles of the Eastern League. This was a humiliating demotion and ended Strang’s major-league career. New York sportswriters adored him. They reported that “Nicklin” was released by the Giants because few people knew him by that name.67 Strang had played under the name “Sammy Strang” to shield the Nicklin family from negative publicity; ironically, the New York press used the Nicklin name to shield Strang.

McGraw was criticized for letting Strang go. Sportswriter and former major leaguer Sam Crane called Strang “the greatest utility player the game ever saw.”68 Strang was a key member of Baltimore’s 1908 Eastern League championship team, which was managed by Jack Dunn and owned by Ned Hanlon; Strang was the leadoff hitter and stole 36 bases.69 Strang and McGraw remained on good terms. In the offseason after the 1908 season, Strang worked as a cashier at McGraw’s billiard hall in Manhattan.70 His playing career ended when the Orioles released him in August 1910, but by then he had embarked on a successful coaching career.

From 1909 to 1917, Strang was the head baseball coach at the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York, where he was known as “Coach Sammy Strang.” As of 2014, his cumulative .711 percentage is the highest winning percentage of any Army baseball coach, and his 1915 team’s .857 percentage is the highest winning percentage of any Army baseball team.

Strang coached many cadets who rose to great prominence in the Army. Below is a partial list of his ballplayers who served as generals during World War II. The number of asterisks indicates the highest rank achieved; for example, ** means two-star general. Also shown is the year of graduation from West Point, the player’s primary position on Army baseball teams, and whether he was the captain of the team as a senior.

-

Omar Bradley71 *****, Class of 1915, left field

-

Jacob Devers72 ****, Class of 1909, shortstop

-

Charles Gerhardt73 **, Class of 1917, third base, captain

-

Leland Hobbs74 **, Class of 1915, right field

-

Charles Lyman75 *, Class of 1913, catcher

-

William McMahon76 **, Class of 1917, pitcher

-

Frank Milburn77 ***, Class of 1914, catcher

-

Charles Milliken78 *, Class of 1914, shortstop, captain

-

Robert Neyland79 *, Class of 1916, pitcher, captain

-

Alex Patch80 ****, Class of 1913, pitcher

-

Vernon Prichard81 **, Class of 1915, shortstop

-

Alec Surles82 *, Class of 1911, left field, captain

Dwight Eisenhower83 *****, Class of 1915, did not make the varsity baseball team, but he cheered them on. Strang reminded the cadets, “Your opportunity at West Point is bigger than baseball. I hope you’ll take advantage of it.”84

In the 1914 Army yearbook, Strang is called “the greatest college baseball coach in the country today.” His “success can be summed up in two words – knowledge and enthusiasm. He not only knows baseball from start to finish, but he is very popular with the men and has the happy faculty of drawing out of them their best efforts.”85

In the 1914 Army yearbook, Strang is called “the greatest college baseball coach in the country today.” His “success can be summed up in two words – knowledge and enthusiasm. He not only knows baseball from start to finish, but he is very popular with the men and has the happy faculty of drawing out of them their best efforts.”85

Strang’s best pitcher at West Point was Robert Neyland, who would become famous as the head football coach at the University of Tennessee. In memoirs written in the late 1950s, Neyland devoted several pages to Strang and his coaching methods.86 Neyland considered Strang to be the greatest college baseball coach of all time. Strang was “an authentic genius with a brilliant mind,” wrote Neyland. Off the field, Strang was “a happy-go-lucky guy, witty, and immensely popular” with the Army officers at West Point.

Here are Strang’s basic hitting instructions to college ballplayers, as remembered by Neyland:

-

Assume a comfortable and relaxed stance.

-

Keep your bat on your shoulder; don’t pump, wriggle, or twist yourself into a tense position.

-

Be ready. Go back slowly with your bat as the pitcher prepares to deliver the ball.

-

Start your swing as the ball leaves the pitcher’s hand.

-

Keep your eye on the ball. Stop your swing if the pitch doesn’t look good.

-

If continuing the swing, time the ball. Try to meet it well in front of your body.

-

“Golf” a low pitch; “club” a high pitch.

When waiting for the pitch, a right-handed batter’s left arm should be almost straight, his left hand about letter high, his right forearm horizontal, and the bat approximately vertical.

In a base-stealing lesson, Strang put four men in the field – a pitcher, catcher, first baseman, and second baseman – and a runner on first base. The rest of the team gathered with Strang at the first-base coach’s box to watch the action. The observers were instructed to shout “Go!” or “Get back!” as soon as they recognized whether the pitcher was throwing to home plate or first base. “As a consequence of such close observation by all players, Strang’s teams stole second base almost at will,” wrote Neyland. For example, the 1911 team stole 143 bases in 22 games,87 and the 1913 team swiped 13 bases in one game against New York University.88

As a favor to Strang, McGraw brought his Giants to West Point in the spring of 1914 for a game against the Army team.89 This started an ongoing tradition of a major-league team playing the Army team in the spring. (On March 30, 2013, the New York Yankees defeated the Army squad, 10-5.)

The 1917 Army baseball season was cut short when the US entered World War I in April. Cadets graduated early from West Point and were sent to Europe. Strang enlisted in the Army and served in France as a captain in the 324th Infantry. After the war he turned down a lucrative offer to return to West Point and resume his coaching duties.90 Instead he accepted an offer to return home to Chattanooga and become president and manager of the Chattanooga Lookouts minor-league team, with the understanding that if he kept the team running for three years, he would become owner of the franchise.91 Strang was extremely frugal and kept the team going for eight seasons, despite average home attendance of 1,000 per game. During this period, the team never finished higher than sixth place in the eight-team Southern Association. Strang cheered his struggling team on. After a game in New Orleans, he led his team in song. Fascinated New Orleans fans “grouped in front of the visitors’ bench to hear Strang’s impromptu concert.”92

Strang coveted Leroy “Satchel” Paige, a flame-throwing pitcher who made his professional debut in May 1926 with the Chattanooga White Sox of the Negro Southern League. Sadly, Paige could not play for Strang’s Lookouts because of the color barrier in professional baseball. According to Paige, Strang “wanted me so bad he tried everything to get me into a game” for the Lookouts, and even “offered me $500 to pitch against the Atlanta Crackers – I just had to let him paint me white.”93

In January 1927 Strang lost the sight in his right eye in an automobile accident.94 He had kept professional baseball alive in Chattanooga, and his financial reward came in July 1927 when he sold his stake in the Lookouts for $75,000.95 After selling the team, he retired comfortably. He resided with two of his brothers in the longtime Nicklin family home at 516 Poplar in Chattanooga.96

On March 13, 1932, Strang died in Chattanooga of a perforated ulcer at age 55. The pallbearers were Army officers, and he was buried at the Chattanooga National Cemetery.97 His death was noted in Time magazine.98 A ceremony honored him before the Lookouts game on July 10, 1932. Among the 9,000 attendees were Baseball Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis and John D. Martin, president of the Southern Association.99 A plaque of Strang’s accomplishments was unveiled at the ceremony and was put on display for many years at Engel Stadium in Chattanooga.100 It read:

IN MEMORIAM

SAMUEL STRANG NICKLIN

(SAMMY STRANG)

1876 – 1932

SOLDIER – SPORTSMAN

PRESIDENT – OWNER

CHATTANOOGA BASEBALL CLUB

1919 – 1927

COACH U.S. MILITARY ACADEMY

1909 – 1917

People are still unsure what to call him. His baseball statistics appear under his pseudonym, “Sammy Strang.” Baseball-Reference.com also lists the names, “Samuel Strang Nicklin” (correct) and “Samuel Nicklin Strang” (incorrect).101 The 2012 Army Baseball Media Guide refers to “Sammy Nicklin.”102 He preferred to be called “Strang Nicklin.” Although confusion over his name remains, his legacy is unmistakable. He was a talented and entertaining major-league player; an influential mentor of Army cadets; and a dedicated promoter of Chattanooga baseball.

Confidence, said Strang, is the key to success. A batter “who advances to the plate feeling that perhaps he may not be able to hit the opposing pitcher is lost; he will not hit him, that is certain.” He “must be just as confident of hitting that ball as he is that he can eat a big dinner after the game.”103 To celebrate an Army baseball victory, Strang would raise his voice in song in the West Point mess hall before his team’s big dinner.104

Notes

1 The Howitzer, Yearbook of the United States Corps of Cadets, 1916.

2 Milwaukee Journal, May 14, 1937.

3 Milwaukee Sentinel, August 22, 1943. Journalist E.V. Durling named his six “most colorful” New York Giants: Sammy Strang, John McGraw, Mike Donlin, Larry Doyle, Roger Bresnahan, and Frankie Frisch.

4 Zella Armstrong, The History of Hamilton County and Chattanooga, Tennessee, Volume I (Johnson City, Tennessee: Overmountain Press, 1992).

5 Atlanta Constitution, February 15, 1894.

6 The Sporting News, May 21, 1936.

7 Cedar Rapids (Iowa) Evening Gazette, September 7, 1900.

8 As a 16-year-old in 1893, Strang played one game for the professional Chattanooga Warriors of the Southern Association.

9 Sporting Life, April 14, 1894.

10 Kingsport (Tennessee) Times, February 18, 1930.

11 Duluth (Minnesota) Herald, December 13, 1913.

12 Cleveland Plain Dealer, July 11, 1896.

13 Kansas City Star, July 30, 1896.

14 Galveston (Texas) Daily News, November 27, 1896.

15 Chattanooga Times, April 11, 1920.

16 Cedar Rapids (Iowa) Republican, April 12, 1900.

17 Sporting Life, June 8, 1907.

18 Sporting Life, June 1, 1901.

19 baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Western_League.

20 Sporting Life, September 22, 1900.

21 Topeka (Kansas) Daily Capital, January 31, 1901.

22 St. Louis Republic, June 3, 1901.

23 Cedar Rapids Evening Gazette, May 28, 1901.

24 Omaha Daily Bee, October 8, 1911.

25 New York World, August 21, 1901.

26 New York World, August 22, 1901.

27 Sporting Life, March 22, 1902.

28 Cedar Rapids Republican, June 21, 1899.

29 This record stands as of 2013 and is unlikely to be broken. The most errors by an AL third baseman in recent history were 43 by Butch Hobson in 1978. Typically, the league leader makes about 20 errors.

30 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 27, 1902.

31 Duluth Herald, December 13, 1913.

32 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 3, 1903.

33 Trenton (New Jersey) Times, May 23, 1903.

34 Spalding’s Official Base Ball Guide, 1904.

35 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 2, 1903.

36 Sporting Life, September 26, 1903.

37 Pittsburgh Press, September 15, 1904.

38 Washington Times, February 1, 1905.

39 Sporting Life, April 8, 1905.

40 Pittsburgh Press, March 30, 1905.

41 Michael Betzold, “Mike Donlin,” sabr.org/bioproj/person/3b51e847.

42 Alden Gonzalez, “Fast and Furious: Trout Flies Home to First,” May 3, 2012, losangeles.angels.mlb.com/news/article.jsp?ymd=20120502&content_id=30224574.

43 Pittsburgh Press, April 4, 1905.

44 Kansas City (Kansas) Star, January 12, 1923.

45 New York Evening Post, March 1, 1928.

46 New York Sun, May 26, 1905.

47 New York Sun, July 19, 1905.

48 New York Herald, July 24, 1907.

49 Kansas City Star, February 21, 1924.

50 Kansas City Star, January 12, 1923.

51 Syracuse (New York) Herald, March 16, 1932.

52 New York Sun, August 18, 1905.

53 New York Evening Post, March 1, 1928.

54 Reading (Pennsylvania) Eagle, August 17, 1905.

55 New York Sun, December 29, 1916.

56 New York Evening World, January 12,1909.

57 The Metropolitan Magazine, April 1911.

58 Minneapolis Journal, August 8, 1906.

59 New York Tribune, August 10, 1906.

60 Atlanta Constitution, September 30, 1907.

61 New York Sun, June 23, 1907; New York Times, June 23, 1907.

62 Because of Strang’s singing ability and Southern roots, he was known as “The Dixie Thrush,” according to folklore; however, the extensive research conducted for this biography turned up only one mention of this nickname in articles published during his lifetime.

63 Omaha (Nebraska) Daily Bee, December 3, 1913.

64 Pittsburgh Press, April 15, 1903.

65 Motor Age, Volume 8, Class Journal Company, 1905.

66 Washington Evening Star, October 20, 1907.

67 Lowell (Massachusetts) Sun, June 23, 1908.

68 Auburn (New York) Citizen, July 31, 1908.

69 Spalding’s Official Base Ball Record, 1909.

70 New York Press, December 24, 1908.

71 From D-Day through the end of World War II, General Omar Nelson Bradley commanded all US ground forces invading Germany from the west. The Bradley tank is named after him. He was an outstanding hitter on Army baseball teams and batted .383 in 1914. He had a remarkable throwing arm.

72 General Jacob Loucks Devers commanded the 6th Army Group of 12 American and 11 French divisions during World War II. He was an assistant baseball coach at West Point from 1914 to 1916. As athletic director from 1936 to 1938, he had new baseball diamonds constructed at West Point.

73 Major General Charles Hunter Gerhardt commanded the 29th Infantry Division, which landed at Omaha Beach on D-Day. He had the highest batting average in college baseball in 1915.

74 Major General Leland Stanford Hobbs commanded the 30th Infantry Division, which landed at Omaha Beach. “Home Run” Hobbs led the 1914 Army baseball team with a .390 batting average and six home runs. He was selected as the right fielder on the 1915 Vanity Fair All-American College Baseball Team. The Cincinnati Reds tried to sign him to a contract, but he chose to stay in the Army.

75 During World War II Brigadier General Charles Reed Bishop Lyman commanded the 21st Regiment of the 24th Infantry Division, which fought the Japanese in the Southwest Pacific. He and his brother Albert were the first Hawaiians to become Army generals.

76 Major General William Claude McMahon commanded the 8th Infantry Division, which landed at Omaha Beach, and he served as assistant chief of staff of the 15th Army Group.

77 Lieutenant General Frank William Milburn commanded the 83rd Infantry Division and the XXI Corps during World War II, and the I Corps during the Korean War.

78 Brigadier General Charles Morton Milliken was commander of Camp Crowder, Missouri, during World War II, where soldiers were trained for duty as radio operators and telegraphers.

79 Brigadier General Robert Reese Neyland, Jr. was commander of supply services in the China-Burma-India Theater of Operations (renamed the Burma-India Theater of Operations in October 1944) during World War II. He had a 35-5 record, including 20 consecutive wins, pitching for Army baseball teams. As of 2014 he was the Army career leader in pitching victories. In 1914 he threw the first no-hitter in Army baseball history. In 1915 Strang said Neyland “would be as sensational as Walter Johnson” if Neyland pitched in the major leagues. Neyland was selected as the “first-choice” pitcher on the 1915 Vanity Fair All-American College Baseball Team. (George Sisler of the University of Michigan was the “third-choice” pitcher on the team.) After serving in France during World War I, Neyland returned to West Point, where he was an aide to superintendent Douglas MacArthur and an assistant football coach. In 1926 Neyland became the head football coach at the University of Tennessee, where he compiled an .829 winning percentage over 21 seasons. Neyland Stadium in Knoxville, Tennessee, is named after him.

80 During World War II General Alexander McCarrell Patch, Jr., commanded US forces that defeated the Japanese in the Battle of Guadalcanal, and he commanded the Seventh Army, which liberated southern France.

81 Major General Vernon Edwin Prichard commanded the 1st and 14th Armored Divisions during World War II.

82 Brigadier General Alexander Day Surles was in charge of the Army’s Bureau of Public Relations during World War II. In this role, he walked a tightrope between keeping the public informed about wartime activities while protecting military secrets to safeguard the troops. He led the 1910 Army baseball team with a .313 batting average.

83 General Dwight David Eisenhower said that failing to make the Army baseball team was “one of the greatest disappointments of my life, maybe the greatest.” Making the Army baseball team was not easy; each year about 80 cadets tried out for the team.

84 Colonel Red Reeder, Omar Nelson Bradley: The Soldiers’ General (Champaign, Illinois: Garrard Publishing, 1969).

85 The Howitzer, Yearbook of the United States Corps of Cadets, 1914.

86 Autobiographical manuscript of college days, General Robert Neyland Papers, MS 1890, University of Tennessee Libraries, Knoxville, Special Collections.

87 The Howitzer, Yearbook of the United States Corps of Cadets, 1912.

88 New York Times, March 30, 1913.

89 Newburgh (New York) Evening News, April 27, 1973.

90 Former major leaguer Hans Lobert succeeded Strang as coach of the Army baseball team.

91 Eau Claire (Wisconsin) Leader, January 18, 1919.

92 Esquire, January 1935.

93 Leroy “Satchel” Paige, Maybe I’ll Pitch Forever (Lincoln, Nebraska: Bison Books, 1993).

94 Kansas City Star, January 30, 1927.

95 The Sporting News, July 14, 1927.

96 The research for this biography found no mention that Strang was ever married or had any children. It seems he was a lifelong bachelor.

97 Chattanooga Times, March 14, 1957.

98 Time, March 28, 1932.

99 Kingsport (Tennessee) Times, July 11, 1932.

100 David Jenkins, Baseball in Chattanooga (Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2005). Engel Stadium opened in 1930 on the grounds of the old Andrews Field where Strang’s Lookouts played.

101 baseball-reference.com/players/s/stransa01.shtml, visited August 2014.

102 http://issuu.com/armyathletics/docs/2012_army_baseball_media_guide/117.

103 Janesville (Wisconsin) Daily Gazette, November 25, 1905.

104 Colonel Red Reeder, Assembly magazine, West Point Alumni Foundation, Spring 1970.

Full Name

Samuel Strang Nicklin

Born

December 16, 1876 at Chattanooga, TN (USA)

Died

March 13, 1932 at Chattanooga, TN (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.