Paul Giel

Great anticipation existed regarding which sport Paul Giel would play after finishing his degree in physical education at the University of Minnesota. As a two-time all-American in both baseball and football, he had his choice of pursuing a career in either sport. In 1954 the Chicago Bears of the National Football League (NFL) drafted him in the ninth round with the 102nd overall pick. The Winnipeg Blue Bombers and the Toronto Argonauts of the Canadian Football League (CFL) both offered Giel contracts to play for them. Instead, Giel decided to test his skills at baseball and signed with the New York Giants as a bonus baby. The amount that he signed for is unclear, but it was somewhere between $50,000 and $80,000 for three years. The Giants figured he would eventually become a star pitcher and that they could survive the early years of his career, which would be rocky. Unfortunately, Giel never got out of the rocky stage and his baseball career was full of potential that never came to fruition. However, once his baseball career was over, he wasn’t done with sports.

Great anticipation existed regarding which sport Paul Giel would play after finishing his degree in physical education at the University of Minnesota. As a two-time all-American in both baseball and football, he had his choice of pursuing a career in either sport. In 1954 the Chicago Bears of the National Football League (NFL) drafted him in the ninth round with the 102nd overall pick. The Winnipeg Blue Bombers and the Toronto Argonauts of the Canadian Football League (CFL) both offered Giel contracts to play for them. Instead, Giel decided to test his skills at baseball and signed with the New York Giants as a bonus baby. The amount that he signed for is unclear, but it was somewhere between $50,000 and $80,000 for three years. The Giants figured he would eventually become a star pitcher and that they could survive the early years of his career, which would be rocky. Unfortunately, Giel never got out of the rocky stage and his baseball career was full of potential that never came to fruition. However, once his baseball career was over, he wasn’t done with sports.

Mr. Gopher, Paul Robert Giel, may be best known for his impressive college football career at the University of Minnesota, but his life as a sportsman was more than that. He was an all-around sports star from a very young age. He was born on September 29, 1932 in Winona, Minnesota, where he grew up with three siblings, Edward Jr. (born July 21, 1929), Lawrence (May 5, 1931), and Ruth (February 20, 1934), and played football, basketball, and baseball. His father, Edward Sr., born in Indiana, was of German heritage and worked as an engineer for the Chicago & North Western Rail Road Company, and their mother, Marion Flannery, was born in Minnesota and was of Irish heritage.

As early as age 14, Giel was making headlines in the local newspaper for his sports feats. He set the midget-league basketball half-season record with 175 points. After basketball season, he stepped onto the baseball field, and the achievements were non-stop. On Opening Day he pitched a one-hitter with ten strikeouts. A little more than a week later, on June 13, he struck out 21 batters in a seven-inning game. The following month he only got better, when he pitched a no-hitter for the Federal Bread team versus the Merchant Banks team with 19 strikeouts in seven innings. Giel was overpowering his competition with his fastball, and scouts like Angelo “Tony” Giuliani were starting to take notice of his dominance.

In 1948 and 1949, when he was still in high school, Giel played shortstop for the Rollingstone team of the Bi-State League (a Minnesota amateur league). Coming out of high school in 1950, Giel pitched for the Winona Braves of the Class B Hiawatha Valley League, where he threw another no-hitter. After he graduated, six or seven major-league teams interviewed him, including the Chicago Cubs, Brooklyn Dodgers, and New York Giants. He could have signed a contract with any one of them and jumped right into their minor-league system. However, since he wanted to stay close to Minnesota, he decided instead to attend the University of Minnesota to pursue football. He believed that by going to the University he could also improve his baseball skills with four years of training under coach Dick Siebert. His first year at Minnesota (1950) also happened to be the last year for legendary football coach Bernie Bierman. Under Bierman the team had been a powerhouse for many years, winning five national championships. However, in the last few years of his tenure the team had slipped, and the fans had become unhappy. Many fans saw the addition of Giel to the football team as the start of an effort to rebuild and regain its national status. Due to rules at the time, Giel was not allowed to play as a freshman, but he sat on the sidelines for many of the games and learned a great deal from Bierman. He may not have been able to play football or baseball for the college teams his first year, but he was able to play town ball for the Winona Braves, where he had a 5-0 record in 1951.

Giel joined the Gophers football team as a quarterback, but soon new coach Wes Fesler turned him into a passing halfback and punter as part of the team’s single-wing offense. Giel started with a bang; in his first five games he had 805 yards, 263 of them running and 542 of them passing, to go along with his 37.5 yard punting average. It was clear that Giel could become a star on the gridiron if that’s what he chose.

Getting his first chance to pitch for the Gophers in the spring of 1952, Giel went 5-0 in Big Ten play with 43 strikeouts and a 0.42 earned-run average (ERA). He was elected to the first of three All-Big-Ten teams that he would be selected to. When school ended he once again returned to pitch for his hometown of Winona, but this season it was for the Chiefs of the Class AA Southern Minny League. He was named to the All-Star team and finished the season with a 6-3 won-list record with 85 strikeouts and an ERA of 2.56 in 59 2/3 innings. His baseball season was shortened due to a severely pulled muscle in his left leg. Gophers fans were worried that it would not only end his baseball but also his football career. The injury would delay his progress in training camp, but he was back to full strength in time for the football season

In 1952 the whole country was taking notice of Giel’s football skills. The Gophers were improving, and Giel was carrying them. In the season’s final game, versus Wisconsin, Giel had one of the best performances of his football career. He ran for 111 yards on 29 carries and scored a touchdown. He completed nine of 19 passes for 167 yards and two touchdowns, to go with his 252 yards punting for a 42-yard average. Unfortunately the game ended in a 21-21 tie. For all his hard work, he was named All-American on three different teams: Associated Press, Chicago Tribune, and Look. Heisman Trophy voters recognized Giel’s great talent when he placed third in the voting, behind winner Billy Vessels (Oklahoma) and Jack Scarbath (Maryland). He was only a junior at the time.

On the baseball field, it was another good season for Giel. In Big Ten games he had a 2-2 record with 58 strikeouts in 41 2/3 innings to go with a 1.73 ERA. On May 3 he showed his strength by pitching seven innings in the first game of a doubleheader versus Michigan and then pitching a full nine innings in the second game. Less than a month later, in the last inning of the last game of the year, Giel felt a popping in his arm. Again fans’ concerns regarding his football and baseball career at Minnesota, as well as with the Winona baseball team, became apparent. He was able to recover but instead of playing for Winona that summer he joined Reserve Officers Training Corps (ROTC). As part of ROTC, he was committed to complete two years of military service, which would later slow his baseball career.

For the 1953 football season Giel was named team captain. His greatest game of the year came against Michigan when he had 57 touches on 73 plays, ran for 112 yards, passed for 169 yards, and led the team in tackles to go with two interceptions, while also doing the punting. The Gophers beat the Wolverines for the first time in 11 seasons, by a score of 22-0. It was an important game for the two teams because it was the 50th anniversary of the battle for the Little Brown Jug. Giel’s triple threat of running, passing, and punting could not be ignored. He was named the Big Ten Conference Player of the Year for the second time. For the second year in a row, he finished second for The Sporting News outstanding football player of the year, this time behind Johnny Lattner (Notre Dame) by a point total of 232 to 248. Every major football award for the season would be a battle between Lattner and Giel as they were the only two players named to all 10 major All-American teams. The voting for the Heisman Trophy was similar as it came down to Lattner and Giel, with Lattner coming out ahead, 1,850 votes to 1,794, one of the closest votes in Heisman history. In the three years that Giel was on the football team, the Gophers finished with a 10-13-4 record. Giel ended his career at Minnesota with 2,188 rushing yards and 1,922 passing yards. In 1975 he would be inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame.

People were still keeping an eye on Giel on the baseball field to see how he was progressing. Yogi Berra was seen talking to him for the Yankees at Toot Shor’s restaurant in New York. Tigers Muddy Ruel and John McHale brought him to Briggs Stadium in Detroit for a tryout. What they saw from Giel was a 1-3 record in the Big Ten and a conference-leading number of strikeouts. For his three years on the baseball team he finished with a 21-8 overall won-lost record. For the second time Giel was named to the All-American baseball team, but this time he made the first team instead of the second team. He was the first person to be named All-American in both football and baseball in two different seasons. At the end of his Gophers career there was a movement by the students to get his number 10 jersey retired by the school. The problem was that the school had never retired a jersey before, and it was not going to start with Giel because it would be seen as disrespectful to former Gopher greats who did not receive the same honor. Eventually the school would retire both his baseball and football numbers.

After college, there was one more venture into town ball before joining the major leagues. Gophers baseball coach Dick Siebert had convinced Giel to come pitch for him on the Litchfield Optimists team. People were critical of Giel for pitching again and risking an injury just before he was set to sign a big contract. Giel was heavily scouted by professional teams in both baseball and football, but there was some question about how much he was actually going to be able to help a team. Because he was a member of ROTC in school, he was required to serve two years in the military, which would take away from his playing time. Giel had to weigh his options between the Bears of the NFL, Blue Bombers of the CFL, and any number of baseball teams. All Giel knew of Bears owner George Halas was that he was cheap, so he was not likely to sign with them. Moreover, Giel believed that he would have to play exclusively as quarterback in the NFL, and he was not interested. The Blue Bombers had territorial rights for Giel and the open field and high speed of the CFL would fit well with Giel’s style of football. However, the team was not offering as much money as he could make playing baseball. Every major-league baseball team had some level of interest in signing Giel except for the Phildelphia Athletics, Baltimore Orioles, and Pittsburgh Pirates. On June 9, 1954 Giel traveled to Milwaukee to meet up with the New York Giants, who were there for a series against the Braves. He signed with the team and right away was placed on the team’s major-league roster because he was classified as a bonus baby. Any amateur player who signed a contract for over $4,000 at the time was classified as a bonus baby, which meant he had to stay on the major-league roster for two full calendar years or be subject to be drafted by other teams at the end of the season. This rule was designed to stop the wealthy teams from signing players and hiding them in their minor-league system. Most bonus players sat on the bench for two years, seeing little game action before they were sent down to the minor leagues. Giel was no different in this regard.

Giel got to the Giants training camp in Arizona in 1954 as a highly respected prospect but quickly learned that the fastball that had dominated all the way through college was not going to be enough at the major-league level. When Hall of Famer and Giants farm director Carl Hubbell first saw Giel, he made a statement that would often be repeated during Giel’s career: “Giel could win in the big leagues as soon as he learned a third pitch.” Pitching coach Frank Shellenback and teammates Sal Maglie, Marv Grissom, and Larry Jansen would all try to teach the young star to throw a change-up. He worked for years on trying to learn a third pitch, but he could never master one.

The first game in which he saw any action was during a Red Cross exhibition game against the Boston Red Sox. Giants manager Leo Durocher watched his young prospect warm up before the game and became worried about how bad his pitches were looking. As it turned out Durocher was right. Giel pitched six innings and had five strikeouts, but he also gave up five walks and a grand slam to Grady Hatton. His real major-league debut started out much better, versus the Pirates on July 10. He faced three batters—George O’Donnell, Gair Allie, and Vic Janowicz—and struck them all out. Much like his first season with the Gophers, Giel sat on the bench watching and learning for most of the year. He only would get into five more games and pitch another 3-1/3 innings. It cannot be found in his major-league record, but August 11 must have been a special game for Giel even if it was only an exhibition game. The Giants were playing their minor-league affiliate, the Minneapolis Millers, at Nicollet Park. Giel had been to Nicollet Park to cheer on the Millers many times in his youth and even got to know some of the players during the days he was being scouted. Giel started the game and went five innings before being replaced.

The Giants would go on to win the 1954 World Series in four games against the Cleveland Indians, but Giel was there only as a spectator. He was eligible to play in the Series, got a ring, and was awarded a full share of the winnings, but he did not pitch in the Series. Giel did not participate in the clubhouse celebration, most likely because he did not feel that he had contributed to the team’s victory. Instead he was sitting in a corner trying to learn new pitching grips for the 1955 season. After the season was over, he took his first step into what would be a productive career in broadcasting. He had a weekly Sunday afternoon sports show in Minneapolis with newspaper writer Sid Hartman and sports announcer Jack Horner. Giel also had another show the same day every week that recapped the NFL games.

In spring training of 1955, Giel was trying to make the starting rotation as the fourth starter. Durocher was giving him regular starts and expected big things out of his bonus baby when he said, “Watch Paul Giel in 1955! He’s going to do a lot of pitching for us. And he’s going to be as great a credit to baseball as he was to football.” In a poll taken by the sportswriters during training camp, Giel was voted as the best-looking Giants player, which only added to his Golden Boy image.

When the regular season came along, things had not worked out as well as Giel and Durocher had hoped. Giel made two starts that year, but for most of the season he was working out of the bullpen because he could not crack the rotation of Johnny Antonelli, Jim Hearn, Ruben Gomez, and Sal Maglie. The season started very well for him as he did not give up an earned run in his first four games and, in one of those games, even got out of a bases-loaded, no-out situation in the 11th inning before losing in the 12th inning, the first loss of his major-league career. On June 15, he earned his first big-league win when he entered a game in the seventh inning against the Chicago Cubs and pitched three scoreless innings. He helped himself with the bat that day, leading off the top of the ninth with a double, setting off a five-run rally that broke a 2-2 tie. When asked about the win he reflected back to the previous season by saying, “I am glad I finally have been able to do something for the Giants. I felt embarrassed accepting a World Series ring last fall, because I had done nothing to earn it.” When the season was over, Giel had a won-lost record of 4-4 with a 3.39 ERA in 82 1/3 innings. The season ended with the Giants in third place, 18½ games behind the first-place Brooklyn Dodgers. Everyone said his goodbyes and hoped to see each other the next season, but for Giel it would be two years before he pitched in the major leagues again. Before leaving for his military duty he went back to Minnesota and did some reporting for the local newspaper covering the Gophers football team.

As part of his joining ROTC in college, Giel had committed to serving two years of active duty in the military. On November 11, Giel was shipped to Aberdeen, Maryland, as a second lieutenant for the Army. After leaving Aberdeen, he was stationed at Fort Dix, New Jersey; Vaihingen, Germany; and Stuttgart, Germany, where he would spend the most time. While in Stuttgart he pitched and coached for one of the military baseball teams, which won 12 of 13 games one year and won the Western Conference baseball championship of Germany the following year. He also coached one of the army football teams but was unable to play because of clauses in his baseball contract. However, the biggest event that happened to Giel in Germany was finding and marrying the woman who would be his wife for nearly 50 years. Nancy A. Davis was the daughter of Colonel Thomas Davis, stationed in Vaihingen. Nancy attended George Washington University and the University of Colorado. The couple planned to live in Winona when Giel’s active duty was over.

Back in the United States for the 1958 season, Giel would not be returning to the New York Giants but the San Francisco Giants. While he was away the team’s owner, Horace Stoneham, had moved the team to California with promises of better attendance and larger profits. Because Giel had signed his original baseball contract in the middle of the season, he still had half a season left to fulfill on the two-year requirement for bonus players to stay on the major-league roster. However, in February the majors rescinded the two-year requirement and dropped the bonus status for all players. The Giants were now free to send Giel to the minor leagues, where he could get more playing time and have a better chance to learn the ever elusive third pitch that he needed. At first Giants manager Bill Rigney wanted to test Giel in spring training to see if he had matured enough in his two years away from the game to make the team. Rigney was also undecided about using Giel either as a starter or a relief pitcher when he said, “I’m going to see how I’m set up on my pitching before deciding whether to use Giel in relief or as a starter, but I think he’s fine relieving material. He wants to be a good pitcher and doesn’t beat himself. Paul is as strong as an ox and he can stand a lot of work. He can almost work every day, if he pitches only a few innings.”

Giel’s change-up was looking good in spring training, and he was able to make the club out of camp as a relief pitcher again. He pitched two games with the Giants before he was optioned to the team’s Class AAA team in Phoenix on May 5. With Phoenix he was 3-0 with a 2.77 ERA. When he was brought back to the Giants on May 21, he was tried as a starter, but in less than a month he was back to working out of the bullpen. However, in that time as a starter he had one shining moment in which he pitched a complete game, allowing only four hits and one run for a victory against the Pirates. Overall, it was not a good year as he finished up 4-5 with a 4.70 ERA. Rigney summed up Giel’s season and was looking toward the next when he repeated what had been said about Giel for his whole career, “Paul needs to develop a change-of-pace pitch, but maybe we can bring him into camp early next spring and have him work on a change-up.” Off the field things were going much better with the birth of his first son, Paul Jr., on July 8. During the offseason Giel worked as a sales representative for the Minneapolis office of Investors Diversified Services, Inc.

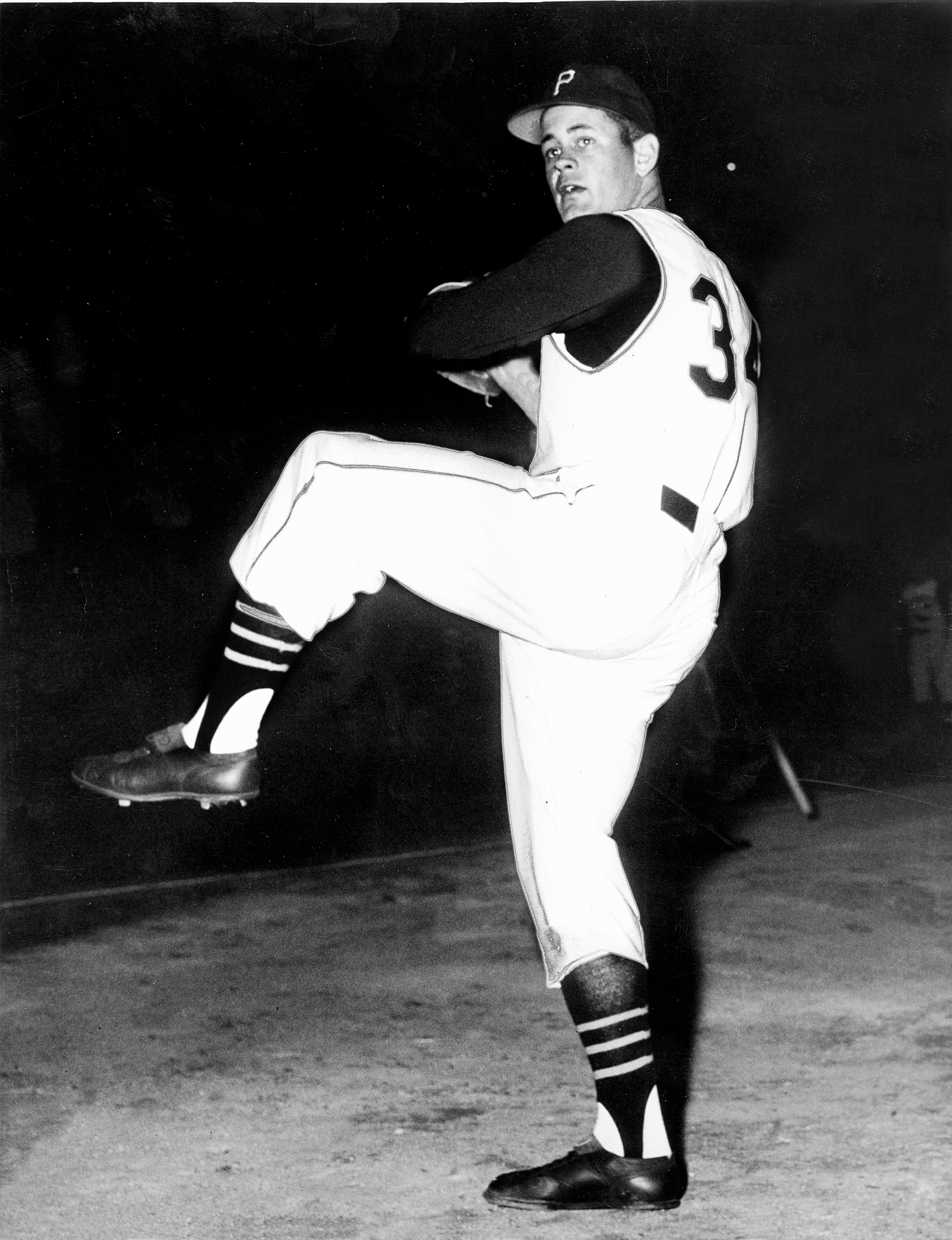

Giel went to spring training with the Giants in 1959 and was expected to be a part of the team. Soon after training started he ran into problems: He walked the pitcher with the bases loaded in one game and give up five runs in one inning in another. Before the Giants broke camp for San Francisco they had decided to waive Giel. The Pittsburgh Pirates were quick to pick him up on April 13 for the $20,000 waiver price. He lasted four games with the team before he was demoted to the Pirates’ Class AAA team in Columbus, Ohio, where he would spend the rest of the season. In that fourth game with the Pirates he gave up six runs in one inning against his former team. Before he was shipped to Columbus, Giel played in an exhibition game at Midway Stadium against the St. Paul Saints. It was a bittersweet game, so close to his home while about to be sent to the minors. He went six innings against the Saints, beating them 6-3 and driving in two of the runs himself. With Columbus, Giel would once again become a starter, going eight and nine innings in his first two starts. However, on July 29 he suffered a hairline fracture in his pitching hand when he was struck by a ball from the bat of Buffalo’s Bobby Morgan. He was out until mid-August because of the injury. The Columbus Jets finished second in the International League behind the Buffalo Bisons.

Giel was invited to play with the Pirates in their 1960 spring training in Fort Myers, Florida, but he was expected to start the season in Salt Lake City playing for the Bees. However, as spring training went on, Giel was looking better and better because he had added to his pitching repertoire. As described by sportswriter Les Biederman “Giel has added a screwball and a slider and looked fine the first time he tested his new deliveries. There’s an outside chance he might crash the roster.” He went on to later say, “Giel . . . really has been the No. 1 star in training camp. . . . Few gave him a chance to win a regular job. But Giel was determined to make good or quit baseball and devote full time to the investment business in Minneapolis.” Giel said that the biggest boost in his confidence came during a game against the Washington Senators, when he entered with the bases loaded and no outs to face Harmon Killebrew. Killebrew doubled and emptied the bases, but Giel proceeded to retire the next three batters by getting Bob Allison to foul out and striking out both Jim Lemon and Julio Becquer. On May 27, with the season just over a month old, Nancy gave birth to the couple’s second child, daughter Gerilyn. On June 7 in a game against the Cubs, Giel suffered a slight muscle pull in his leg that was traced back to a football injury he had received in college. Giel pitched just 33 innings for the Pirates in 16 games, compiling a 2-0 record, all in relief before being sent down to play for the Salt Lake City Bees on July 15. In Salt Lake he was thrown into the starting rotation, getting nine starts in his 13 games with the team, but could only muster a record of 0-3.

In Minnesota, the people were happy about major-league baseball coming to the Twin Cities with the transfer of the Washington Senators for the 1961 season. Minnesota fans had been watching the high-caliber baseball of the Minneapolis Millers and the St. Paul Saints for years and could not be dazzled by ordinary baseball skills. Due to their need for a unique connection to the area, the Twins front office was looking for someone with whom the fans would identify. The easy answer was bring back the hometown golden boy to the area for the fans to come see play. This is exactly what the Twins did when they purchased Giel’s contract from the Pirates in February of 1961. Fans from Giel’s hometown, Winona, chartered a plane up to the Twin Cities for the home opener to cheer on Giel and the rest of the Twins. Pitching coach Ed Lopat, like every other pitching coach who had worked with Giel, tried to teach him a third pitch. Lopat’s pitch of choice was a change-up screwball. Giel only lasted 12 games with the team and had a few bad outings. In one game he gave up seven earned runs in a third of an inning to the Kansas City Athletics. In another game, against Baltimore, he walked in what turned out to be the winning run. The last win of his career came on May 25 against the Tigers. He replaced Jim Kaat in the 11th inning and retired the first three batters that he faced. The Twins pushed across a run in the bottom of the 11th. A week later the hometown hero was traded with Reno Bertoia to the Athletics for Bill Tuttle.

Giel refused to report to the Athletics, instead deciding to retire from baseball. The Twins officials talked to Giel and got him to agree to stay in baseball and play for the Athletics. However, one day after the trade Giel pitched his first game for the Athletics and shelled by the Washington Senators for seven runs in 1 2/3 innings. Giel again announced his retirement, and this time it was for good. Athletics owner Charles Finley was upset that he had given up Bill Tuttle for a player who would retire after his first day with the team. He wanted to be compensated for Giel’s services by the Twins and took his argument to Commissioner Ford Frick. Finley claimed that Giel had told him that he had previously informed Twins officials that he was going to retire from baseball and that the Twins did not disclose that information to the Athletics before making the trade. Twins owner Calvin Griffith ended up paying the Athletics $20,000 to make up for the loss of Giel’s services and to complete the trade.

Giel may have been finished with baseball, but he was far from done with sports. Capitalizing on Giel’s Minnesota fame, the newly formed Minnesota Vikings football team hired him in 1961 as an assistant business manager; he would stay for two seasons. In 1963 he traded on his past experience as a broadcaster and became the sports director for WCCO radio and television. For 10 years he coordinated coverage of sports programming. During his tenure with WCCO, his second son, Tom, was born on Christmas of 1967.

Giel had already done a great deal of good for the advancement of sports in the state of Minnesota, but his next venture would be one of his largest contributions. On December 12, 1971 the University of Minnesota announced that Giel would become the director of athletics. He was going back to the place where he had gained most of his fame. However, instead of trying to help a troubled football team as he did in the 1950s, this time he was trying to help the whole struggling sports department. He took on the job knowing that the sports department was $500,000 in debt, but he was able to turn the debt into a surplus during his 16-year tenure. The Gophers won a number of championships during the years that Giel directed the athletic program: two national hockey titles, three Big Ten baseball titles, three men’s gymnastics championships, and a men’s basketball Big Ten championship. Giel is also credited with the hiring of some important team coaches, such as Lou Holtz (football) and Clem Haskins (basketball). However, one of the proudest moments for Giel as the Gophers’ athletic director actually had little to do with Gophers sports. It was his connection to the United Sates hockey team’s “Miracle on Ice” victory when they beat the Soviet Union at the 1980 Olympics. The head coach for the team, Herb Brooks, and many of the players were from Minnesota. Giel was proud that the sports program at the University was able to make such a large contribution to the historic event.

There were many turbulent times at the University, as well. When basketball coach Bill Musselman left the school for the American Basketball Association, it was later discovered that under his tenure the team had more than 100 National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) violations. Giel had to deal with the fallout of NCAA sanctions and the loss of scholarships. In 1986, another incident with the basketball team occurred in Madison, Wisconsin, when three players were accused and arrested for sexually assaulting a young woman. The players were later acquitted, but Giel, who was not involved in the incident, still took a lot of heat from people for letting his players act in such a disturbing manner. In 1988 there was a scandal with the Gophers football team from which Giel was unable to recover and that was partially instrumental in his losing his job. The university’s interim director of the office of minority affairs, Luther Darville, was caught giving money to student-athletes and breaking NCCA rules. Darville was convicted of stealing $200,000 of the university’s funds, although he claimed that he gave the money to student-athletes at the request of his superiors at the school.

After leaving the University of Minnesota Giel was an executive at the Minneapolis Heart Institute Foundation. By the age of 56, Giel had already received a quadruple bypasses and an angioplasty, so it was a cause that he was able to identify with very closely. On May 22, 2002 Giel passed away at the age of 69 from a heart attack after leaving a Twins game on his way to his grandson’s Little League game. Even in his last moments he was a true sports fan and dedicated family man. Giel will always be remembered as one of the greatest sports figures in Minnesota history: from his slashing runs and long passes as a Gophers football player, to his blazing fastball for the Winona Braves and Minnesota Gophers, and for his off-the-field accomplishments of broadcasting sporting events with WCCO and his abilities as a decision-maker while directing the athletic department at the University of Minnesota.

A version of this biography appeared in the book “Minnesotans in Baseball,” edited by Stew Thornley (Nodin, 2009). This biography is also included in the book “Sweet ’60: The 1960 Pittsburgh Pirates” (SABR, 2013), edited by Clifton Blue Parker and Bill Nowlin. For more information or to purchase the book in e-book or paperback form, click here.

Sources

Steve Bitker. The Original San Francisco Giants: The Giants of ‘58. (Champaign, IL: Sports Publishing, 1998)

College Football Hall of Fame. Retrieved July 26, 2008, from National Football Foundation’s College Football Hall of Fame Web site: http://www.collegefootball.org/famersearch.php?id=50061.

Genealogy.com – Family Tree Maker Family History Software and Historical Records. Retrieved July 27, 2008, from Genealogy.com Web site: http://www.genealogy.com/index_r.html.

Frank Litsky (May 26, 2002). Paul Giel, 70, All-American in Two Sports and Pro Pitcher. New York Post.

Paul Giel. Retrieved July 27, 2008, from Retrosheet web site: http://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/G/Pgielp101.htm.

(November/December 1988). Paul Giel: I wanted to go to 59. Twenty Years. Minnesota, 36-39.

Armand Peterson and Tom Tomashek. Townball: The Glory Days of Minnesota Amateur Baseball. (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006)

Patrick Reusse (May 30, 2002). Baseball did Giel a disservice. Minneapolis Star Tribune, 1C.

SABR Minor Leagues Database: Paul Giel. Retrieved July 27, 2008, from SABR Minor League Database Web site: http://minors.sabrwebs.com/cgi-bin/person.php?milbID=giel–001pau.

Chip Scoggins (May 30, 2002). Paul Giel: 1932-2002; Giel is remembered; Services for former Gopher Paul Giel recalled his stature as a man as well as his exploits as an athlete. Minneapolis Star Tribune, 10C.

Sports Reference LLC. “Paul Giel” Baseball-Reference.com – Major League Statistics and Information. Retrieved July 26, 2008 from http://www.baseball-reference.com/g/gielpa01.shtml.

Steve Treder (November 1, 2004). Cash in the cradle: The Bonus Babies. The Hardball Times, Retrieved July 26, 2008 from http://www.hardballtimes.com/main/article/cash-in-the-cradle-the-bonus-b….

University of Minnesota Archives (2008) Paul Giel Folder 1.

Minnesota Daily 1953-1954.

The Sporting News 1953-1964.

Winona Republican-Herald 1946.

Full Name

Paul Robert Giel

Born

September 29, 1932 at Winona, MN (USA)

Died

May 22, 2002 at Minneapolis, MN (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.