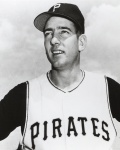

Jim Umbricht

Determined to make the major leagues since he was a young boy, Jim Umbricht paid his way to a minor-league tryout camp and, after making the team, was converted from shortstop to pitcher. After he returned from serving two years in the military, Umbricht worked his way up to the majors and then spent three seasons playing sporadically for the Pirates. After the Houston Colt .45s selected him in the expansion draft, Umbricht turned into one of his hometown club’s most trusted late-inning relievers in 1962. Umbricht was diagnosed with cancer in spring training of 1963, but was back pitching in the majors within two months and had another fine season in the bullpen. Tragically, the cancer returned and Umbricht died before the 1964 season began, robbing major-league baseball of a fine relief pitcher, and more importantly, of a courageous, optimistic, and considerate man.

Determined to make the major leagues since he was a young boy, Jim Umbricht paid his way to a minor-league tryout camp and, after making the team, was converted from shortstop to pitcher. After he returned from serving two years in the military, Umbricht worked his way up to the majors and then spent three seasons playing sporadically for the Pirates. After the Houston Colt .45s selected him in the expansion draft, Umbricht turned into one of his hometown club’s most trusted late-inning relievers in 1962. Umbricht was diagnosed with cancer in spring training of 1963, but was back pitching in the majors within two months and had another fine season in the bullpen. Tragically, the cancer returned and Umbricht died before the 1964 season began, robbing major-league baseball of a fine relief pitcher, and more importantly, of a courageous, optimistic, and considerate man.

James “Jim” Umbricht was born in Chicago on September 17, 1930, to Mr. and Mrs. Eduard Umbricht. Eduard’s parents were from Illinois and he was born and raised in the state. Jantina Frank, Eduard’s wife, was born in Holland to a Dutch mother and German father. She was a native German speaker. The couple married on April 24, 1920, and had three children by the time of the 1930 US Census. William was eight years older than James and Eduard Jr. was a year older. Eduard Sr. worked as a banker and the family appeared to be relatively well-off, as they had a servant.

Jim wanted to be a baseball player from his early childhood and Eduard Jr. recalled that Jim would be outside every day during the summer playing pickup baseball until dusk.1 During Jim’s childhood, Eduard Sr.’s job required that the family to move to Decatur, Georgia. Jim attended Decatur High School and won all-state honors in basketball and baseball in 1948, his senior year.2

Umbricht was awarded a scholarship to the University of Georgia, where he played basketball and baseball for the Bulldogs and was awarded letters three times in each sport. The tall right-hander was also asked to play football, but declined for fear that an injury would derail his aspirations in baseball. In 1951 he was named the shortstop for the All-Southeast Conference team.3 Umbricht was the captain of both the basketball and baseball teams in his senior year.4

Although his first love was always baseball, Umbricht was a talented basketball player, as well. Louisiana State University star Bob Pettit, Jr., who later played in the NBA, won the league MVP award twice, was named to 11 NBA All-Star teams and was inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame, said of Umbricht, “He scored 50 points against us. We used three men on him and it didn’t mean a thing.”5

After graduating with a degree in education, Umbricht paid his way to a tryout camp in 1953 for the Waycross Bears of the Class D Georgia-Florida League, a team that did not have a major-league affiliation. He impressed the scouts, who were intrigued by the right-hander’s 6-foot-4, 215-pound frame, and was signed to the team. Although he played a fair amount of shortstop, managers Alvin Aucoin and Morton Smith also used Umbricht as a pitcher. He hit .246 in 179 at-bats over 54 games, but made perhaps a more noticeable contribution on the mound. Pitching 69 innings, Umbricht posted a 2.87 ERA, the second-lowest mark on the team. As one might expect from a new pitcher still learning his craft, Umbricht struggled with his control, walking 41 batters.

With the military draft still in effect, Umbricht spent 1954 and 1955 in the Army. He began to focus more extensively on pitching when he got the opportunity to play baseball with other service members. While stationed in Fort Carson, Colorado, he struck out 18 in an Army tournament game in 1955.6

Umbricht returned to Organized Baseball the following season with the Baton Rouge Rebels of the Class C Evangeline League, another team with no major-league affiliation. He continued to split his time between the mound and shortstop, throwing a team-high 235 innings and playing in 45 games as a position player and pinch-hitter. Again he was more successful on the mound. Umbricht’s 3.37 ERA was the lowest of the team’s starters, and he showed signs of development by cutting his walk rate noticeably. Because of his willingness to contribute to the team in any way possible, Umbricht was presented with a trophy as the “hardest working Rebel of 1956.”7 After the season his contract was sold to the Milwaukee Braves.

The Braves assigned Umbricht to the Topeka Hawks of the Class A Western League in 1957. He went 13-8 and again led the starters in ERA with a 3.24 mark over 178 innings. He saw some duty as a pinch-hitter, but it was evident that his future in professional baseball was as a pitcher.

After the season, Umbricht played winter ball for the Carta Vieja Yankees, who won their third consecutive Panama League pennant. Finishing with a 6-2 record, he threw a four-hitter for the Yankees in the pennant-clinching game.8

The following season, 1958, marked a change for “Big Jim,” as he was occasionally known; he was used primarily as a reliever for the first time in his career. Of his team-high 54 appearances for the Atlanta Crackers of the Double-A Southern Association, only 12 were starts. He was used as a multi-inning reliever, as his 173 innings pitched were the third highest on the club. That winter, Umbricht returned to play winter ball for the Carta Vieja Yankees.9

Before the 1959 season, the Braves traded Umbricht to the Pittsburgh Pirates for minor-league outfielder Emil Panko. Pirates scout Howie Haak had always liked Umbricht because “he was young, strong and could throw hard.” Haak recalled that the team had given up on Panko by that point and the teams were able to work out a deal fairly easily.10

The Pirates assigned Umbricht to the Salt Lake City Bees of the Triple-A Pacific Coast League for 1959. Umbricht made 42 relief appearances and five starts. He finished second on the team with 14 wins, and had the seventh-lowest ERA in the league at 2.78. Umbricht walked only 43 batters, his lowest walk rate in any minor-league season.

This was perhaps Umbricht’s best minor-league season and he was rewarded with a September call-up. He reported to the Pirates on September 13 and four days later Umbricht celebrated his 29th birthday in the major leagues. Within a couple of weeks he made his big-league debut when he was given the starting assignment against the Cincinnati Reds on September 26, 1959. Umbricht had a particularly memorable first inning, but not in a positive way, as leadoff hitter Johnny Temple, Frank Thomas, and Buddy Gilbert all took him deep for home runs. Umbricht stayed in the game and left in the seventh inning with a 6-5 lead, but the Reds won the contest with two runs in the bottom of the ninth. That was his only appearance for the Pirates that year, but he played winter ball again, this time for Aguilas Cibaenas in the Dominican Republic.11

Umbricht turned some heads in spring training in 1960 when he combined with Benny Daniels to no-hit the Tigers in Fort Myers, Florida. He broke camp with the club and started the third game of the season. After struggling in two starts, Umbricht was sent to the bullpen. He earned his first major-league win on May 28 by pitching scoreless 12th and 13th innings against the Philadelphia Phillies before Don Hoak hit a walk-off home run. On June 28 the Pirates sent him to Columbus of the International League, where he returned to the rotation and won eight games with a 2.50 ERA and two shutouts. Recalled in September, he went back to the bullpen, pitched twice, and finished the season with a 1-2 record and a 5.09 ERA. He did not pitch in the World Series.

Although he began the 1961 season in the majors, Umbricht didn’t pitch until May 5, when he appeared in a blowout loss. Three days later he was sent down to Columbus, where he again spent most of the season in the rotation. Umbricht posted a 9-6 record with a 2.35 ERA, which was the lowest of any pitcher on the club with at least 10 starts. His standout performance was a one-hitter against Richmond on August 25 with nine strikeouts, where the only blemish was an eighth-inning single to second base. He showed further signs of improved control, bringing his walk rate down to below a batter every three innings.

Despite his continued minor-league success, the Pirates chose not to protect Umbricht for the expansion draft, and he was selected by the Houston Colt .45s.12 This was a nice surprise for Umbricht, as his parents had moved to Houston and he also lived in the city in the offseason.

Umbricht made his mark as a major-league pitcher with the Colt .45s. He began the 1962 season in the bullpen and didn’t allow an earned run in his first six appearances. However he was sent to the minors on May 9 after allowing two runs to the Dodgers in a loss. It was reported that Houston didn’t want to send Umbricht down, but he was the only pitcher who could be optioned to the minors without being exposed to waivers.13 After spending the previous few years going back and forth between Triple-A and the National League, Umbricht was disappointed in the demotion, even if he understood that options necessitated the move in the club’s view.14

He continued to serve primarily as a reliever for Houston’s Triple-A affiliate, posting a 3-4 record and a 3.39 ERA for the Oklahoma City 89ers. Umbricht still felt he hadn’t merited the demotion and that it wasn’t beneficial to him, later stating, “I didn’t change anything or pick up anything new at Oklahoma City.”15

On July 16, Umbricht was recalled and he pitched in both games of a doubleheader the day after his arrival. With his fine overhand curveball, Umbricht settled into the role of late-inning reliever and had a solid season. He struck out the side against Cincinnati on August 26 for his second major-league save. Umbricht won four games in September, pitching 4? one-hit innings against the Pirates for his first victory of the season. In September, he pitched in three straight games against the pennant-winning Giants, striking out Felipe Alou and Orlando Cepeda in the first game, picking up the win in the second and striking out Willie Mays and Alou consecutively in the third. Umbricht posted a 2.01 ERA in 67 innings and finished 4-0. He didn’t struggle with his command as he had in his previous exposure to the majors, striking out 55 batters and walking 17. He attributed his success partly to getting regular work, as opposed to his infrequent deployment by the Pirates.16

Umbricht said the demotion by the Colt 45’s had motivated him. “It was disappointing to be sent back so many times, but it made me keep trying,” he reflected. “If I had had family responsibilities, I may have quit and looked for more security. But baseball is my life. They’ll have to tear this uniform off me. I’m 32, but I’m a young 32 because I didn’t actually get to pitch until I was 25.”17

During spring training in 1963, Umbricht was golfing with Houston general manager Paul Richards when he mentioned a mole he had noticed on the back of his right leg. He recalled, “I just felt this lump. No soreness, no pain, no nothing.”18 Richards suggested that Umbricht have the lump examined.19 The team physician referred Umbricht to the M.D. Anderson Cancer Clinic in Houston, and after two days of examinations, he was diagnosed with a malignant cancer that had already spread. The next day, March 7, Umbricht underwent a six-hour operation to remove the growth. Cancer was removed from his groin, thigh, and leg.20 He later recalled, “Everything happened so fast I didn’t have time to think about or worry about cancer.”21

Umbricht was not prepared to let the cancer diagnosis end his baseball career. He told a sportswriter, “I told them that they wouldn’t be able to keep me in here on Opening Day.”22 Nevertheless, Umbricht made the most of his time in the hospital, spreading positivity and optimism among other patients. Houston trainer Jim Ewell said, “He served as an inspiration for other patients and believe me, he cheered up many of the patients.”23

Umbricht left the hospital on March 25 and began running at Colt Stadium on April 2.24 A month after his operation, he was in uniform on Opening Day.25 “The last 30 days have been an eternity. And the next 30 will be twice as long,” he said.26

Umbricht spent a month on the disabled list but began pitching batting practice on April 22 and, with 100 stitches in his leg, he was back in Houston’s bullpen on May 9. “No one has to feel sorry for me,” he said. “…It’s all a little embarrassing. I don’t mean to sound ungrateful, though. I’m glad people are so interested in one respect, because it helps publicize cancer. Early detection of cancer is a big thing, and maybe if people read about how I was cured it might help them.”27 On his first day back in the bullpen he pitched an inning of relief against the Reds. Three days later, he picked up a win when Bob Aspromonte hit a walk-off home run against Chicago after Umbricht pitched two scoreless innings.

Umbricht spent a month on the disabled list but began pitching batting practice on April 22 and, with 100 stitches in his leg, he was back in Houston’s bullpen on May 9. “No one has to feel sorry for me,” he said. “…It’s all a little embarrassing. I don’t mean to sound ungrateful, though. I’m glad people are so interested in one respect, because it helps publicize cancer. Early detection of cancer is a big thing, and maybe if people read about how I was cured it might help them.”27 On his first day back in the bullpen he pitched an inning of relief against the Reds. Three days later, he picked up a win when Bob Aspromonte hit a walk-off home run against Chicago after Umbricht pitched two scoreless innings.

Umbricht made three starts during the season, two of them defeats. In one game, he faced off against Warren Spahn and the great southpaw threw a complete game shutout. However, Umbricht nearly matched him with seven innings of four-hit, one-run ball and eight strikeouts. It was Umbricht’s best major-league start.

Umbricht finished his major-league career with 9 2/3 scoreless innings over four appearances, allowing only four hits and a walk and striking out nine. Umbricht picked up a win in relief in what turned out to be his last major-league appearance, against the New York Mets on September 29. In 35 games he finished with a 4-3 record and a 2.61 ERA in 76 innings. He struck out 48 and walked 21. Umbricht posted a 2.33 ERA in his final 143 major-league innings (encompassing 1962 and 1963) and settled into a role as a dependable late-inning reliever for the Colt .45s. He was the only pitcher to record a winning record in both of the team’s first two seasons. GM Richards deemed Umbricht so valuable to the club that he named him as one of the players he would trade only for “first-line major league talent.”28

It has been reported that Umbricht was informed in November that his cancer was incurable.29 He didn’t let that news deter him in his efforts to beat the disease and underwent treatment three times a week during the offseason in Houston. With special permission of the National League, the Colts released Umbricht on December 16 and then signed him to a scout’s contract without having to place him on waivers. It was understood that the team would return Umbricht to the player roster once he was healthy again.30

Early in 1964, the Philadelphia Sportswriters Association honored Umbricht at a dinner as the most courageous athlete of 1963.31 In accepting the award, Umbricht displayed his positive attitude, remarking that the illness was “sort of a blessing” in that “six weeks in a hospital bed gives you time to think – and come out a better human being. I’m sure everything will come out all right.”32

Umbricht spoke during the offseason about trying to stay busy playing cards and golf. Golf was one of Umbricht’s strengths and he was known, along with catcher Jim Campbell, as the best golfer on the Houston club.33 He hinted at the psychological impact of the illness when he said, “I don’t like to go to bed early. I just lay there and think too much.”34

On the first day of the Colts pre-spring-training workouts, Umbricht tried to work out and found it too draining, telling Whitey Diskin, the Houston clubhouse attendant, “Whitey, I just can’t make it.”35 He was too sick to attend spring training and he was hospitalized again on March 16.36 It soon became apparent that no amount of courage or willpower would defeat the disease.

Umbricht appeared to recognize this and, although he hoped to see Opening Day of the 1964 season, he began to put his affairs in order. He wrote to Houston sportswriter Clark Nealon, “I want to thank you for the many nice things you’ve written about me in the past year.”37 After he was hospitalized again, the Colt .45s hosted a postgame radio show after a spring-training game so that Umbricht could hear his teammates’ voices again. Sportswriter Mickey Herskowitz wrote that the purpose of the call was unstated but evident. “They were saying goodbye to Umbricht, dying in his hospital room in Houston, and they knew it. So did Umbricht.” Some of Umbricht’s teammates were too choked up to appear on the show and those who did often talked about two of Umbricht’s favorite topics, golf and cards.38

On April 8, 1964, five days before the Colt .45s played their season opener, 33-year-old Jim Umbricht died of melanoma. He was survived by his parents and his brother, Ed.

The Colts canceled their last spring-training game, which was on the day of his funeral. Russ Kemmerer, an old teammate and friend who was playing for Houston’s Oklahoma City farm club, gave the eulogy. Colts front-office personnel, manager Harry Craft, coach Luman Harris, and teammates Bob Lillis, Dick Farrell, and Ken Johnson, who was one of Umbricht’s closest friends and his roommate on road trips, all attended the service. Umbricht’s ashes were spread at the construction site for the Houston Astrodome.

The tributes to Umbricht poured in from all sources. Richards called Umbricht “one of the finest competitors I’ve ever known on or off the field.” He added, “He was a great inspiration for our club. We will not forget Jim Umbricht. And we will miss him more than we know.”39 His physician said, “He never accepted the possibility of his baseball career being ended. He was a great inspiration to other patients and all who came in contact with him.”40

In his memory, the Colts wore black armbands during the 1964 season.41 On Opening Day Ken Johnson pitched 8? innings in a 6-3 victory. After the game, he said, “I had an extra special reason for wanting to win this one. My ex-roommate.”42

Although Umbricht had been embarrassed by the attention given to him, he had been optimistic that the publicity may lead to in earlier cancer detection in others. He achieved this goal at least once, as Jack Pardee, a 28-year-old linebacker for the National Football League’s Los Angeles Rams, who had recently noticed a mole on his arm, realized that it sounded identical to the mole that had signaled Umbricht’s melanoma.43 Pardee stated, “The way the papers described it, it sounded exactly like what I had. I made an appointment to see the doctor the next morning.”44 Pardee was diagnosed with malignant melanoma and underwent surgery to remove the growth. He missed the 1965 NFL season while recovering, but returned to play several more seasons before becoming a head coach in the NFL, college, and the Canadian Football League. At the time, Pardee reflected, “I don’t know how long I might have put it off if I hadn’t read that story. I felt fine and … when you’re feeling good you hate to see a doctor.”45

Houston retired Umbricht’s number 32 – the first retired number in franchise history – on April 12, 1965, and hung his jersey in the Astrodome, the home of the Houston Astros. As a tribute to Umbricht’s courage and positivity, the franchise renamed its team MVP award the Jim Umbricht Memorial Award.46

Last revised: March 15, 2021 (ghw)

This biography is included in the book “Sweet ’60: The 1960 Pittsburgh Pirates” (SABR, 2013), edited by Clifton Blue Parker and Bill Nowlin. For more information or to purchase the book in e-book or paperback form, click here.

Notes

1 Loran Smith, “Big League Ball Was Always Umbricht’s Goal,” Athens (Georgia) Banner-Herald, February 21, 2003.

2 Ray Kelly, “Colts .45 Hurler Overcame Cancer,” Philadelphia Evening Bulletin, January 28, 1964.

3 “Jim Umbricht Dead; Pitcher on Colts, 33,” New York Times, April 8, 1964.

4 Loran Smith, “Big League Ball Was Always Umbricht’s Goal,” Athens Banner-Herald, February 21, 2003.

5 Baseball Hall of Fame Library, player file for Jim Umbricht.

6 Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

7The Sporting News, September 5, 1956, 37.

8The Sporting News, February 12, 1958, 25.

9The Sporting News, November 5, 1958, 24

10Lester J. Biederman, “Scout’s Memory Enabled Pirates to Land Umbricht,” Pittsburgh Press, March 24, 1960.

11The Sporting News, October 7, 1959, 33.

12 “Jim Umbricht Dead; Pitcher on Colts, 33,” New York Times, April 8, 1964.

13 Clark Nealon, “Umbricht Made It Big as Colt After Years on Major Pogo Stick,” Houston Post, February 24, 1963.

14 Ibid.

15 Ibid.

16 Ibid.

17 Ibid.

18 Ray Kelly, “Colts .45 Hurler Overcame Cancer,” Philadelphia Evening Bulletin, January 28, 1964.

19 Loran Smith, “Big League Ball Was Always Umbricht’s Goal,” Athens Banner-Herald, February 21, 2003.

20 Mickey Herskowitz, “Umbricht Now One of the Boys; Long Wait Is Over,” Houston Post, May 9, 1963.

21 Lester J. Biederman, “Colts’ Jim Umbricht Recovering From Cancer Operation,” Pittsburgh Press, May 1, 1963. Most sources report the diagnosis as being made on March 6 and the operation occurring on March 7. At least one source reports the diagnosis as being made on March 7 and the operation occurring on March 8 (Mickey Herskowitz, “Jim Umbricht,” The Sporting News, May 25, 1963, 21).

22 Clark Nealon, “Colts’ Jim Umbricht Showing ‘Most Satisfactory’ Progress,” Houston Post, March 27, 1963.

23 Lester J. Biederman, “Colts’ Jim Umbricht Recovering From Cancer Operation,” Pittsburgh Press, May 1, 1963.

24 Mickey Herskowitz, “Jim Umbricht,” The Sporting News, May 25, 1963, 21.

25 “Jim Umbricht Dead; Pitcher on Colts, 33,” New York Times, April 8, 1964.

26 Mickey Herskowitz, “Umbricht Now One of the Boys; Long Wait Is Over,” Houston Post, May 9, 1963.

27Ibid.

28 Clark Nealon, “Ten First-Year Phenoms Land on .45 Roster,” The Sporting News, October 26, 1963, 19

29 Clark Nealon, “Umbricht Carried Battle Against Dread Cancer Into Extra Innings,” Houston Post, April 9, 1964.

30 “Jim Umbricht, Colt Pitcher, Dies of Cancer,” The Morning Record, April 9, 1964.

31 Ray Kelly, “Colts .45 Hurler Overcame Cancer,” Philadelphia Evening Bulletin, January 28, 1964.

32Ibid.

33 Mickey Herskowitz, “Umbricht Fidgets While .45s Pitchers ‘Duel in the Sun,’ ” Houston Post, March 6, 1963.

34 Ray Kelly, “Colts .45 Hurler Overcame Cancer,” Philadelphia Evening Bulletin, January 28, 1964.

35 Clark Nealon, “Umbricht Carried Battle Against Dread Cancer Into Extra Innings,” Houston Post, April 9, 1964.

36“Colts to Wear Black Arm Bands for Jim Umbricht,” The Day, New London, Connecticut, April 9, 1964.

37 Clark Nealon, “Umbricht Carried Battle Against Dread Cancer Into Extra Innings,” Houston Post, April 9, 1964.

38 Mickey Herskowitz, “Strength, Courage and Humor – A Legacy Umbricht Left Behind,” The Sporting News, April 25, 1964, 25

39 Clark Nealon, “Umbricht Carried Battle Against Dread Cancer Into Extra Innings,” Houston Post, April 9, 1964.

40 “Colts Umbricht Loses Fight for Life; Cancer Victim,” The Sporting News, April 18, 1964, 44.

41“Colts to Wear Black Arm Bands for Jim Umbricht,” The Day, April 9, 1964.

42 Earl Lawson, “Local Boy Jim Wynn Makes Cincinnati Suffer,” The Sporting News, April 25, 1964, 22.

43 “Umbricht Death May Have Saved Pardee,” Tuscaloosa (Alabama) News, May 7, 1964, 8.

44Ibid.

45Ibid.

46 Loran Smith, “Big League Ball Was Always Umbricht’s Goal,” Athens Banner-Herald, February 21, 2003.

Full Name

James Umbricht

Born

September 17, 1930 at Chicago, IL (USA)

Died

April 8, 1964 at Houston, TX (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.