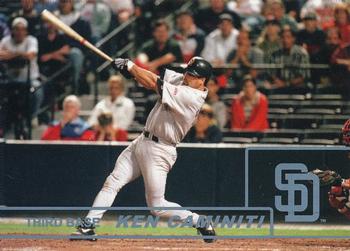

Ken Caminiti

The life of Ken Caminiti parallels the path of a classic Greek tragedy. He was an athlete blessed with extraordinary physical abilities who diligently worked to develop those gifts and dedicated himself to achieving excellence. A tough, tireless leader on the field, he climbed to the highest levels of the baseball world. Then, at the brink of greatness, he was seized by internal demons that drained his talent and forever scarred his success. In the end, rather than being considered one of the best of his era, he is most often remembered as a sad victim of baseball’s steroid subculture.

Kenneth Gene Caminiti was born on April 21, 1963, in Hanford, California, a bustling community in Central California’s San Joaquin Valley. He was the youngest of three children. From the time he could hold a ball, Kenny played whatever sport was in season. Through those early years his biggest fan and regular chauffeur was his mother, Yvonne. In high school he excelled at baseball and football, playing in California’s prep all-star football game as a senior. Though he loved football, his future was in baseball. Kenny shined as a high-school shortstop. His father, Lee, was an engineer who worked on defense projects at Lockheed Martin in Sunnyvale, California. Yvonne was a homemaker taking care of three children — Glenn, Ken, and Carrie. She later worked at Lockheed Martin herself as the administrative assistant to the head of one of the programs at Lockheed.1

Lee Caminiti, who had played semipro baseball, taught his son about the game, including how to switch-hit. The lessons led to a scholarship at nearby San Jose State University following a freshman year at San Jose City College. At San Jose State he earned Sporting News All-American status and a spot on the 25-man US Olympic squad, but was among the final four players cut from the 21-man squad that went to the Olympics.2 Impressed by his achievements and talent, the Houston Astros selected him in the third round of the June 1984 amateur draft.

Caminiti’s professional baseball career began in 1985 with the Osceola Astros in the Class-A Florida State League. A 6-foot switch-hitter with a powerful physique, above-average speed, and a cannon arm, he was an acquisition whom the Astros organization immediately worked to develop. In 1985, Kissimmee, Florida, in Osceola County, was a good place to become a professional ballplayer. Like Caminiti, the area was new to professional baseball. During the previous winter the Class-A Astros relocated from Daytona Beach to Kissimmee. With the move came a new ballpark that would serve as the Astros’ spring-training facility and, from April until early September, the home of the Osceola Astros. Only a handful of Caminiti’s new teammates had played for Daytona Beach the season before but most had played somewhere in the minor leagues. Caminiti, or “Cami” as his teammates soon called him, was one of only two on the roster with no previous professional experience.

The season opened on a rainy mid-April night against the new Daytona Beach Admirals. Batting seventh, Caminiti started at third base, contributed one hit and an RBI, scored two runs and made a key play in the 9-8 win. By the end of the week, he had been moved up to third in the batting order. He stayed at the heart of the lineup throughout the rest of the season.

The next couple of weeks went well for the Astros and their rookie third baseman. By early May, the team was in first place in the league’s Central Division. Caminiti was a key part of that success. He was leading the team in RBIs and runs scored. He had also begun to establish a reputation as a clutch player. In a game against the Tampa Tarpons, he knocked in the winning run on a ninth-inning single.3 Over the next few months he repeated the achievement nine more times, more than anyone else in the Florida State League. When asked about his transition to professional baseball, Caminiti reported: “I feel very little pressure. … I think my biggest challenge is learning how to hit with a wooden bat again.”4

Through the summer Caminiti established himself as one of the better players in the league. In July he was one of seven Astros selected for the league all-star game. At the time he led the league in RBIs and was third in runs scored.5 His defensive skills had also begun to earn some accolades. He ended the season with the highest batting average, .284; most RBIs, 73; and most hits of any Osceola player who had spent at least half of the season in Kissimmee. He also banged out a team-record 26 doubles.6 It was clear that the young third baseman had adjusted well to wooden bats and Class-A pitching.

Along with a dozen Osceola teammates, Caminiti began the 1986 season on the Double-A Columbus (Georgia) Astros in the Southern League. It was the next step up the Houston minor-league ladder. The team started slowly, finishing the first half in last place. Caminiti, on the other hand, picked up where he had left off the previous season. Batting in the middle of the Columbus order, he continued to be among his team’s leading RBI producers. During the second half, the team reversed its fortunes. Climbing into first place, the Astros defeated the first-half champion Jacksonville Expos in a playoff. They then beat the Huntsville Stars to claim the league championship.7 Ending the season with a .300 batting average, Caminiti was again among his team’s leaders in several hitting categories.

The 1987 season began with Caminiti back in Columbus. While his team struggled a bit early, Cami did not. His batting average remained above .300 through the first three months of the season and he was among the league leaders in both RBIs and home runs. In July, along with Astros pitcher Rob Mallicoat, Cami was selected to the league’s all-star team. The all-star game turned out to be the last time that Caminiti wore a Columbus uniform. On July 16 he was called up to Houston.

Caminiti’s major-league debut was spectacular. On the first play of a game against the Phillies, he made a diving catch and bullet throw to get speedy Juan Samuel. Over the next couple of innings, he made several more outstanding plays in the field. After the game Philadelphia manager Lee Elia lamented, “(Caminiti) just defensed the heck out of us.”8 As notable as his play in the field had been, it was his times at the plate that really impressed. Leading off the fifth, his second plate appearance, he drilled a triple off the right-center-field wall. Two innings later he crushed his first major-league home run. In the ninth, with the score tied, 1-1, he worked a one-out walk. Two hitters later center fielder Gerald Young banged out a single that brought Cami home with the winning run. After the game Caminiti, who two days earlier thought he was being called up to the Triple-A Tucson Toros, commented, “This might be the highest high I’ve had. I knew it could happen. I just didn’t know it would be this fast.”9 Manager Elia put it more succinctly: “That is a heck of a way to break into the majors.”10

The week that followed was almost as good. The day after his debut, Caminiti added two singles to his hit collection. He got his first double, another single, a run scored, and an RBI a day later. Throughout his first week, the hits and runs kept coming. He ended his first week as a major leaguer with a .500 batting average and two home runs, and was named the National League’s Player of the Week. It was an auspicious start.

Through much of the rest of the season, Caminiti remained the Astros’ starting third baseman. At the plate his average slid to .246 but in the field he continued to impress. Meanwhile, Houston remained in the National League West pennant race before slumping badly in September. Reflecting the disappointment that others in the organization felt, manager Hal Lanier commented, “Nobody’s happy with the way we played last year, especially in the latter stages of the season.”11 At the same time, he acknowledged that “The acquisition of Caminiti and Young did good things for our ballclub.”12

Caminiti came to spring training in 1988 with a new wife (he married his high-school sweetheart, Nancy Smith, during the offseason), a new contract, and great hopes of becoming the Astros’ starting third baseman. “Lots of people I’ve talked to seem to think I have the job wrapped up. That’s just not true I am going to go into spring training with the attitude I had when I got here,” he said.13 One of those who did not think Caminiti had the job wrapped up was Hal Lanier. The Astros manager considered the position open, saying, “It’s not going to be given to Ken just because he ended up the year there.”14 Lanier had no concerns about Caminiti in the field but was not as confident about him at the plate, especially from the right side.

Spring training did not go as Caminiti had expected. Early on it became clear that Lanier had already penciled in veteran Denny Walling as the team’s starting third baseman. Consequently, Caminiti was competing with Chuck Jackson, the player he had replaced the previous July, for the backup role. Jackson got off to a quick start. Caminiti did not. His ability to hit from the right side became a particular concern. Midway through camp, a $500 fine for being late to two practices further stymied the young third baseman’s chances. By the last week of spring training, Caminiti’s playing time had dwindled significantly. His spring play ended well, a home run from both sides of the plate in a game against the Phillies, but a day later, as the team prepared to head home to Houston, Caminiti was sent to Tucson.

The reassignment rankled Caminiti. He complained, “I think if they wanted me to play there (third base) they would have let me have more at-bats and worked with me more. … This is probably my biggest downer. It hurts.”15 A week later he was at third base in the Toros’ Opening Day lineup. Batting in the middle of the Tucson order, Caminiti was expected to add some power.16 He did not disappoint. Through the first month of the season he drove in runs on an almost daily basis. He also began to re-establish a reputation as a clutch player. It was a role he enjoyed: “I live for the tough ones.”17 Then, in early May, trying to protect a teammate in an on-the-field fracas, he tore a ligament in his right thumb. The injury kept him on the bench for a week and when he returned he struggled a bit. During the next month his batting average dropped almost 30 points and his run production slowed. Emerging from the slump in mid-June, Caminiti started pounding the ball again, renewing speculation that he was soon destined for another call-up to the Astros.

Meanwhile in Houston, the Astros were again having problems at third base. Suffering from chronic back spasms, Denny Walling, the regular third baseman, was not hitting as the team had hoped. On June 20 he went on the disabled list, where he remained until early August. His backup, Chuck Jackson, was also having problems at the plate. The day before Walling went on the disabled list, Jackson was shipped back to Tucson. To plug the hole, the Astros traded with Cincinnati for veteran Buddy Bell. A month later, first baseman Glenn Davis pulled a hamstring and was expected to be out of action for a month. With Davis unavailable, Bell was moved to first and Caminiti was recalled.

Caminiti’s second trip to Houston lasted only three weeks. By the time Walling was ready to return, Caminiti was hitting an anemic .176 and had driven in only three runs. On August 18 he was sent back to Tucson, where he stayed until the September call-ups. He ended the season with the Astros batting just .181 with one home run and only seven RBIs. The end of Caminiti’s season reflected the fate of the Astros. Another dismal September dropped them out of the pennant race and into fifth place in the National League West.

The day after the 1988 regular season ended the Astros fired manager Lanier. A month later they hired Art Howe. It was a change that suited Caminiti well. The new manager soon announced that “Ken Caminiti is my third baseman.”18 Throughout the spring, trade rumors swirled around Caminiti, but he made it clear that “the bottom line is I don’t want to be traded. That’s all there is to it. I want to play in Houston.”19 He also made it clear that he liked playing for Howe: “It’s great playing for Art. He’s fun, he’s stern, and he definitely knows the game. The atmosphere has really changed.”20

Howe’s confidence in Caminiti paid quick dividends. Beginning in an Opening Day win over Atlanta, the Astros third baseman established himself as an integral part of his team, contributing with both his bat and his glove. In an early April game against Cincinnati, he drove in the run that gave the Astros the winning margin and killed a threat with a sparkling play at third. Two days later he scored the winning run in a 15-inning victory over the Dodgers. The next day he hit his first home run of the season to beat the Dodgers again. Another home run in late May beat the Cardinals. Through the first two months of the season, Caminiti continued to contribute clutch hits and was part of numerous rallies that helped keep the Astros near the top of the National League West. By June, few still questioned Caminiti’s place on the team. When asked what he attributed his success to, he responded, “The difference this year is I’m more relaxed. Before, I was tense, wondering if I’d be in the lineup or not. If I got in, I knew I had to produce.”21The season ended badly for the Astros. After battling the Giants through mid-August, the team, for the third year in a row, foundered in September, finishing third, six games behind the division-winning Giants. Though he was disappointed, Caminiti was satisfied with his play. Throughout the season he had been a solid part of the Astros lineup. Playing for the second worst hitting team in the National League, he finished with a respectable .255 batting average, comfortably above the .239 team average. He led the team in doubles, was third with 10 home runs and second with 72 RBIs. In the field he established himself as one of the outstanding third basemen in the league. By the end of season, he looked forward to being the Astros’ third baseman for years to come.

For the next five seasons Caminiti remained a Houston fixture at third base, where his acrobatic stops and rifle arm regularly dazzled patrons. He also became part a young team core. Craig Biggio was another of those central players between 1990 and 1994. Caminiti and Biggio had come up from Tucson together and shared similar struggles during their initial season. The two became lifelong friends. In 1991outfielder Steve Finley was acquired by the Astros as part of a trade with Baltimore. The same year Jeff Bagwell was brought up from the Eastern League. These four — Caminiti, Biggio, Finley, and Bagwell — became the nucleus of the team through the 1994 season. During the four seasons from 1991 through 1994 Caminiti hit between .253 (in 1991) and .294 (in 1992) while averaging 14 home runs and 73 RBIs. In 1994 he was selected to his first All-Star team. But only in the strike-shortened 1994 season was Houston a legitimate pennant contender.

Off the field Caminiti’s gregarious personality and Hollywood-handsome good looks made him a fan favorite. He was a regular at celebrity golf tournaments and offseason banquets.22 He was also a favorite among his teammates. He trained hard to develop his playing abilities, and frequently played through pain for his team. An unobtrusive enforcer, he was always ready, when appropriate, to defend teammates as well as quietly, but forcefully, rebuke players who were shirking their team responsibilities. His teammates thought enough of him that they elected him to be their representative during 1994 players union confrontation with ownership. His growing salary, steadily rising from $129,000 in 1989 to $4.6 million in 1995, further reflected his value to the team.23

The tensions between the players union and the owners continued throughout the winter of 1994-1995. Among the chief issues of debate was a salary cap. Anticipating the cap, Houston prepared to reduce its total salary costs by trading away several of its high-priced players. Caminiti was at the top of that list. On December 28, 1994, along with five of his teammates, he was traded to San Diego for six Padres players. The 12-player exchange was the fourth largest in the modern era. Caminiti was not happy about the deal. In addition to leaving his home, his teammates and friends, as well as the city he had come to love, he was going to a team with the worst record in the major leagues in 1994.

In most ways, San Diego turned out to be much better than Caminiti had anticipated. While with the Padres he won three consecutive Gold Glove Awards and a Silver Slugger Award, was unanimously voted the National League’s 1996 Most Valuable Player, and helped transform his new team into the 1998 National League pennant winner. But it was also in San Diego that Caminiti set the stage for his own demise.

At the time San Diego acquired Caminiti, the team’s new ownership had just embarked on a rebuilding process. Their new third baseman figured prominently in those efforts. The owners were gambling that Caminiti was on the verge of stardom, and, as an eight-year veteran, could provide leadership. Their gamble paid off. In his first year in San Diego, he produced career highs in batting average, home runs, RBIs, and doubles, and helped the Padres climb out of the National League West cellar. His new manager, Bruce Bochy, later described him as “the guts of the team. … He played with maniacal zeal that left those in his wake astounded.”24 He brought a new level of toughness, intensity, and commitment to the team. Along with Tony Gwynn and Steve Finley, Caminiti and the Padres began a journey that carried them to the World Series three years later.

As well as he played in 1995, Caminiti did even better the following year. Again he produced career highs in every significant offensive category. That year also saw Caminiti’s “tough guy” image grow to near-legendary proportions. Early in the season in a game against the Astros, Caminiti dived for a short flare into left field. Landing hard on his left elbow and shoulder, he tore his rotator cuff. “For the next six or seven days I couldn’t lift my arm,” he said. “I played for a month and a half in pure pain.”25 Through it all, his batting average remained comfortably above .300. Refusing to have season-ending surgery, Caminiti played almost the entire schedule with a severely torn rotator cuff.

Another chapter was added to the Caminiti legend in August. The Padres played a three-game series with the Mets in Monterey, Mexico. Midway through the series, Caminiti and several other players were stricken with food poisoning. Dehydrated, unable to retain food or liquids, and obviously weakened, Caminiti spent the morning of the final game on the clubhouse floor being treated intravenously. However, just minutes before game time, when he saw that he was not in the starting lineup, he confronted his manager and pleaded to start. Reluctantly manager Bochy penciled him in at third base. In his first trip to the plate Caminiti smashed a home run over the right-center-field fence. The next time up he duplicated the feat. After hobbling around the bases for a second time, he was given the rest of the day off. He spent the following two hours getting more IV treatments. In describing the sequence of events, a usually subdued Tony Gwynn marveled, “You had to see it to believe it. What we saw was not normal. It was a superhuman effort.”26 Other teammates confirmed Gwynn’s assessment.

What Gwynn and most others did not know was that Caminiti’s success that day and throughout much of 1996 had been significantly aided by steroids. Aware that other players had gotten through injuries using steroids and that steroids could be bought over the counter just a short drive south of San Diego in Tijuana, Mexico, Caminiti began experimenting. The immediate results were stunning. During the second half of the 1996 season he hit more home runs than he had previously hit in any full season. He finished with a batting average 24 points higher than ever before and drove in 36 more runs than ever before. His success immediately thrust him into the upper echelon of the baseball world, but it also began a tragic journey for Caminiti.

The 1997 season started slowly for the Padres’ new star. Still recuperating from shoulder surgery, in typical Caminiti fashion he was in the Opening Day lineup three months earlier than his doctor had advised. To compensate for the physical limitations and pain, he again resorted to steroids. “The thing is,” he said, “I didn’t do it to make me a better player. I did it because my body broke down.”27 This time he was more methodical about his usage. He found a physician who prescribed a “cycle” of injections. Though not producing as he had during his MVP season, Caminiti remained one of the league’s premier players, elected by the fans as the National League’s All-Star starting third baseman.

The following season, 1998, Caminiti’s production fell again as did his playing time. Over the winter, with the help of steroids, he had built himself up as never before. “I showed up at spring training as big as an ox.”28 Along the way, some of the hazards of steroid use began to plague Caminiti. Frequent hamstring and quadriceps strains, various ruptured tendons and ligaments, and torn muscles limited his time on the field for the rest of his baseball career. He was still an asset to the team, and helped the Padres make it to the 1998 World Series, but he was no longer the reliable force he had been since arriving in San Diego.

Caminiti became a free agent after the 1998 season. In what was described as a cost-cutting effort, the Padres chose not to negotiate a new contract with him. Instead, when the Astros offered him a two-year contract for $9.5 million, he agreed to return to Houston. He had reportedly been offered significantly more money by Detroit but instead, professing, “I think happiness is being with my family, my kids and my wife,” who had remained in Texas while he was playing for San Diego, he chose to return to the Astros.29

Back in Houston Caminiti, despite being surrounded by family, fell into old habits and fed new addictions. He had gone through alcohol rehabilitation during the 1994-95 offseason but had resumed his drinking habits long before returning to the Astros. Beginning in 1997 he also began carrying a “goody bag” packed with assorted pain-relief medications. In the Astros dugout their new third baseman’s pregame “meal” included a mixture of pills and powders that became known as a “Caminiti Cocktail.”30 More dangerously, he expanded his use of steroids. No longer relying on a physician for treatments, he developed his own steroid cycles. At some point he also began using cocaine after games to ease the depression and tensions associated with extensive use of steroids. Disregarding the apprehensions of his coaches and teammates, most notably his friend Craig Biggio, he became less concerned about concealing his medication routine. Despite it all, he performed well during his first season back in Houston. Playing fewer than half the games due to injuries, he pushed his batting average back up to .286 and drove in 56 runs.

Caminiti struggled through two more seasons. The first 10 weeks of 2000 went well. He kept his batting average near .300 and by mid-June had hit 15 home runs. Then on June 16 he went on the disabled list with tendon damage in his right wrist. He finished the season still on the disabled list. After the second and final year of his Astros contract, he again became a free agent. In December 2000, the Texas Rangers signed him with hopes that he would provide veteran leadership and help the team escape the American League West cellar. Caminiti hoped that a fresh start in the American League would revive his career. Neither prospect was realized. Batting only .232, he went on the disabled list with a pulled hamstring in mid-June. On July 2, at his request, he was released. Three days later he was signed by Atlanta. His time with the Braves was no better than his time with the Rangers. In November he again became a free agent but this time there were no takers.

As difficult as his life in baseball had become, his life away from baseball was even more problematic. A Sports Illustrated interview in June 2002 added to Caminiti’s grief. Speaking to writer Tom Verducci for what became a pivotal investigative report, Caminiti admitted that he had begun using steroids during his MVP year in 1996. He further estimated that approximately 50 percent of major leaguers were taking steroids. Coupled with earlier statements by Jose Canseco, the report, “Thoroughly Juiced: Confessions of a Former MVP,” elicited reactions from every corner of the baseball world. Eventually the responses included a congressional investigation that opened a new era of drug testing in professional baseball. For Caminiti the report, while applauded by some, brought scorn from many others. Mets sluggers Mike Piazza and Mo Vaughn, among numerous other players, questioned Caminiti’s motives.31 Phillies catcher Mike Lieberthal questioned his intelligence.32 Chicago Tribune columnist Steve Rosenbloom mockingly proposed, “Guess we have proof that ’roids help your muscles, not your neurotransmitters.”33 To an ESPN radio audience just a few days after the article’s release, Caminiti retracted parts of what he had said: “I never knew the interview was going to go like that. It just got real ugly.”34 However, Verducci’s reporting was too convincing and the effect of the article was too powerful for retractions.

Caminiti’s life continued to unravel after the Sports Illustrated article. To many in baseball he became a pariah. In December he and Nancy divorced. Efforts by family and friends to help had temporary success at best as he continued to swirl down ever more deeply into his addictions. Arrested in March 2001 for drug possession, he was sentenced to three years’ probation which included regular drug tests. Two years later, while still on probation, he tested positive for cocaine and was ordered into a Texas criminal drug-treatment program. In September 2004, after yet again violating probation, he was sentenced to 180 days in jail. Given credit for time already served, he was released from jail on October 5.

Ken Caminiti died five days later. After being released from jail in Houston, he traveled to New York City. On October 10, at a friend’s seedy Bronx apartment, he took one last hit, a speed ball of cocaine and heroin. He immediately suffered cardiac arrest, fell to the floor and died before medical attention could reach him. And so ended the spectacular but tragic life of Ken Caminiti.

In San Diego Caminiti is remembered as the greatest third baseman in Padres history. His friends and family remember him for his generosity, loyalty and dedication; but many others remember him for the role he played in exposing the insidious steroid subculture that had infiltrated professional baseball.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org.

Notes

1 Email from Ken’s sister Carrie Van Solinge on January 17, 2019.

2 San Jose Sports Authority, at SJSA.org/2017-inductees.

3 “Caminiti Sparks Osceola to 8-4 Victory,” Orlando Sentinel, May 4, 1985: 24.

4 Frank Carroll, “Ken Caminiti’s Bat Propels Astros,” Orlando Sentinel April 28, 1985: 268.

5 Tim Hipps, “7 Astros Dot FLS East Roster,” Orlando Sentinel, July 7, 1985: 358.

6 Frank Carroll, “Astros Return to Play 3 Games with Islanders,” Orlando Sentinel, June 15, 1986: 257.

7 “Columbus Astros Fly to League Title,” Orlando Sentinel, September 14, 1986: 279.

8 Sam Carchidi, “Phils fall to Astros in Ninth, 2-1,” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 17: 1987, 30.

9 “Young, Caminiti Lead Houston Past Phillies,” Arizona Daily Star (Tucson), July 17, 1987: 31.

10 Sam Carchidi.

11 “Intending to Contend,” Del Rio (Texas) News Herald, February 21, 1988: 39.

12 Reggie Roberts “Astros Have High Hopes for Andujar,” Austin American-Statesman, January 20, 1988: 39.

13 Ibid.

14 Michael A. Lutz, “Astros Looking to Regain Magic, Consistency of ’86,” Del Rio News Herald, February 21, 1988: 11.

15 “Sambito Cut, Caminiti Sent Down,” Galveston Daily News, April 1, 1988: 17.

16 Ron Somers, “Toros Begin Their Season Tomorrow Against Calgary,” Arizona Daily Star, April 7, 1988: 41.

17 Ron Somers, “Toros’ Sambito earns 1st win,” Arizona Daily Star, June 1, 1988: 47.

18 Larry McCarthy, “Howe’s Pitching Pains Likely to Go Away Soon,” Orlando Sentinel, February 26, 1989: C-10.

19 Bill Haisten, “It’s Final: Caminiti’s a Lock at 3rd; Boggs Trade ‘Dead,’ Galveston Daily News, March 24, 1989: 15.

20 Mike Forman, “Astros Banking on Caminiti,” Victoria (Texas) Advocate, March 25, 1989: 11.

21 “Caminiti Lifts Astros Over Reds,” Austin-American Statesman, April 12, 1989: 53.

22 In 1994 Caminiti did have a brief disagreement with Astros fans. He criticized them because they “come to see a Houston game but cheer for Atlanta.” The hard feelings were quickly rectified. “Home-team Blues,” Victoria Advocate, June 12, 1994: 21.

23 baseball-reference.com/players/c/caminke01.shtml.

24 Scott Miller, The Cautionary Tale of Ken Caminiti: The Steroid Era’s First Truth-Teller,” bleacherreport.com/articles/2224511-the-cautionary-tale-of-ken-caminiti-the-steroid-eras-first-truth-teller.

25 Tom Verducci, “Totally Juiced: Confessions of a Former MVP,” Sports Illustrated, June 2, 2002: 39.

26 Murray Chass, “Caminiti Becomes a Legend in His Time,” New York Times, March 9, 1997: S2.

27 Verducci: 39.

28 Verducci: 40.

29 “Caminiti Rejoins Astros,” Galveston Daily News, November 16, 1998: 15.

30 Scott Miller.

31 Jim Salisbury, “Steroid Use Exaggerated, Big Leaguers Say,” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 30, 2002: E1, E4.

32 Salisbury: E-4.

33 Steve Rosenbloom, “Baseball’s Power Aid,” Chicago Tribune, June 2, 2002: Section 3, 10.

34 “Caminiti Tempers Steroid-Use Claims,” Chicago Tribune, May 31, 2002: 45.

Full Name

Kenneth Gene Caminiti

Born

April 21, 1963 at Hanford, CA (USA)

Died

October 10, 2004 at Bronx, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.