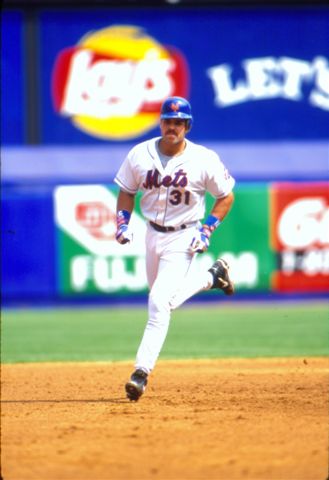

Mike Piazza

On September 21, 2001, amid heavy security, 41,235 fans1 filed into Shea Stadium for the first baseball game to be played in New York City after the September 11 terrorist attacks. Only a week before, the ballpark had served as a staging and relief area for rescue workers, and at the time there was debate over whether it was too soon for sporting events to be held in New York City within miles of Ground Zero. Reflecting on his emotions before the game, Mike Piazza, who had a view of the World Trade Center from his apartment,2 said: “It was just a deep conflict because we wanted to do our part to help people heal, and the game needed to be played for the good of the city, but we knew it was insignificant in the bigger scheme of things.”3

On September 21, 2001, amid heavy security, 41,235 fans1 filed into Shea Stadium for the first baseball game to be played in New York City after the September 11 terrorist attacks. Only a week before, the ballpark had served as a staging and relief area for rescue workers, and at the time there was debate over whether it was too soon for sporting events to be held in New York City within miles of Ground Zero. Reflecting on his emotions before the game, Mike Piazza, who had a view of the World Trade Center from his apartment,2 said: “It was just a deep conflict because we wanted to do our part to help people heal, and the game needed to be played for the good of the city, but we knew it was insignificant in the bigger scheme of things.”3

After an emotional pregame ceremony honoring those lost in the attacks and the rescue and recovery workers, the game, between the New York Mets and Atlanta Braves, was scoreless until the fourth inning. The Braves scored in the top of the frame, and the game was tied when Piazza scored on a sacrifice fly. The Braves took the lead, 2-1, in the top of the eighth inning.

In the bottom of the inning, after a walk to Edgardo Alfonzo with one out, Piazza walked to the plate against Steve Karsay. After taking a strike, he lined a two-run home run to left-center field to give the Mets a 3-2 lead.4 Returning to the dugout, Piazza acceded to the crowd and took a curtain call. The deciding home run was described by Bruce Herman in his book New York Mets: Yesterday and Today as “more than a victory for his team – it carried the very spirit of a city.”5 In the clubhouse after the game, Piazza said: “the hardest thing I’ve ever had to do as an athlete was play that game. We had to win that game.”6

Michael Joseph Piazza was born in Norristown, Pennsylvania, on September 4, 1968, to Vince and Veronica Piazza.7 Vince, a school dropout, worked in self-made businesses – car salesman, real-estate investor, entrepreneur – while Veronica took care of Mike and his four younger brothers.8 Mike grew up as a Phillies fan admiring future Hall of Famer Mike Schmidt. Sitting in second row behind the Phillies dugout where the family had season tickets, Piazza would study Schmidt’s approach to playing the game.9

Growing up, Piazza singular focus was baseball. When he was young, he hit baseballs at a mattress propped against a basement wall.10 Eventually, Vince built Mike a backyard batting cage where Mike hit about 300 balls a day, even in the winter.11 In 1984 Vince through a friend of a friend arranged for Ted Williams to visit their home before appearing at a local card show.12 Williams’s reaction to seeing Mike hit: “I guarantee you, this kid will hit the ball. I never saw anyone who looked better at his age.”13 Before leaving, Williams signed Mike’s copy of his book The Science of Hitting, with the inscription: “To Mike, follow this book. As good as you look now, I’ll be asking you for tickets.”14

Vince Piazza was friendly with Tommy Lasorda, the Los Angeles Dodgers manager, who grew up in Norristown, and at 13 Mike had the opportunity to act as batboy for the Dodgers when they played in Philadelphia. One of the perks of being a batboy was being allowed to take some swings in the batting cage with the Dodgers, and he hit a ball into the seats at Veterans Stadium. When Mike was 14 he was invited to go with the Dodgers to Shea Stadium, and batted there as well.15

Piazza played first base for Phoenixville High School. As a senior, he hit .442 with 11 home runs.16 Even breaking his high school’s career home-run record, Piazza received little interest from major-league scouts, who believed he “couldn’t hit or run.”17 Major colleges were not reaching out to Piazza either. It took a call from Lasorda to Ron Fraser, the University of Miami baseball coach, to give him the opportunity to play.18 Piazza was a backup first baseman during his one year at Miami. He transferred to Miami-Dade North Community College for the next season, and batted .364.19

Piazza’s strong year at Miami-Dade still did not persuade the major-league clubs to consider him a prospect. The Dodgers took him in the 62nd round of the 1989 draft as a favor to Lasorda.20 After the draft, Lasorda had to persuade Dodgers scout Ben Wade, who believed the Dodgers had better prospects at first base, to sign Piazza.21 Lasorda asked Wade if he would sign Piazza if he was a catcher. Wade said he would. Lasorda said, “Well, then sign him. He’s a catcher!”22 Wade signed Piazza that day with a $15,000 signing bonus.23

After his 1989 minor-league rookie season in Salem, Oregon (Northwest League), Piazza volunteered to spend time at the Dodgers’ baseball academy in the Dominican Republic, Campos Las Palmas, becoming the first US-born player to attend.24 He then spent two seasons in Class A before moving up to Double-A San Antonio in 1992. After a little over a month, he was promoted to Triple-A Albuquerque, where he batted .341 with 16 home runs.25 He was a finalist for the USA Today and The Sporting News Minor League Player of the Year awards.26

Piazza was called up to the Dodgers on September 1, 1992, and immediately placed in the lineup. He went 3-for-3 with a double and two singles before coming out for a pinch-runner.27 Piazza finished the season with a .232 average with one home run and 7 RBIs.

Piazza was named the everyday catcher for the Dodgers in 1993. He responded by winning the National League Rookie of the Year Award, finishing the season with a .318 average, 35 home runs, and 112 RBIs. His 35 home runs were the most ever by a rookie catcher28 and his RBIs were tied for the third highest by a National League rookie at the time.

Piazza continued to post impressive numbers during the following two seasons, batting .319 in 1994 with 24 home runs, and .346 in 1995 with 32 home runs. Only Babe Ruth and Ted Williams hit as many home runs and batted for a higher average than Piazza in their first three years.29

In 1996 Piazza batted .336 with 36 home runs and 105 RBIs, and was second in the NL the Most Valuable Player voting behind San Diego’s Ken Caminiti.30 He was the starting catcher in the 1996 All Star Game, at Veterans Stadium, and earned the game’s MVP honors with a home run and an RBI double.31

Piazza batted .362 and hit 40 home runs in 1997, and during 1998 spring training, the Dodgers offered him a six-year, $80 million contract,32 which he turned down in order to test the free agent market at the end of the season. Some teammates were upset with Piazza, including Dodger Brett Butler who said: “Mike Piazza is the greatest hitter I have ever been around. But you can’t build around Piazza because he’s not a leader.”33 Sportswriter Tim Kurkjian wrote, “I also don’t think Piazza was very happy being a Dodger by then. If he was, he would have been thrilled to take that deal. So I think he was ready to move on. I don’t blame him for that. I don’t blame the Dodgers, either. It was time for some new chemistry on that club.”34

On May 15, 1998, the Dodgers sent Piazza and Todd Zeile to the Florida Marlins for Gary Sheffield, Charles Johnson, Bobby Bonilla, Jim Eisenreich, and Manuel Barrios. The players in the deal represented $108.1 million in contracts and 15 All Star Game appearances.35 At the time of the trade, Piazza was batting .282 with 9 home runs and 30 RBIs.36

On May 15, 1998, the Dodgers sent Piazza and Todd Zeile to the Florida Marlins for Gary Sheffield, Charles Johnson, Bobby Bonilla, Jim Eisenreich, and Manuel Barrios. The players in the deal represented $108.1 million in contracts and 15 All Star Game appearances.35 At the time of the trade, Piazza was batting .282 with 9 home runs and 30 RBIs.36

A week later, on May 22, Piazza was traded to the Mets for Preston Wilson, Ed Yarnall, and Geoff Goetz.37 The trade came as a shock to the media, fans, and Todd Hundley, the injured Mets catcher, as Mets general manager Steve Phillips had held that he was not interested in trading for Piazza.38 At least one sportswriter reported that Nelson Doubleday, who co-owned the Mets with Fred Wilpon at the time, wanted the trade to happen because he liked Piazza’s style, toughness, and numbers.39

Arriving only an hour before the Mets game on May 23, Piazza made an immediate impact for his new team.40 While pitcher Al Leiter pitched a four-hitter against the Milwaukee Brewers at Shea Stadium, Piazza energized the crowd of 32,908 as soon as he appeared outside the dugout.41 Piazza received a standing ovation from the fans in the fifth inning when he hit an RBI double to center field.42 His impact also was felt at the box office that afternoon as approximately 13,000 tickets for the game were sold after the trade was announced.43 The box-office effect for the Mets was dramatic the rest of the season; attendance before Piazza’s arrival was 18,112 per game and averaged 34,589 after his arrival.44 Rusty Staub noted in his book Few and Chosen: Defining Mets Greatness Across the Eras: “Piazza immediately changed the culture around the team almost single-handedly. After a decade of malaise, they became relevant again.”45

After the season Piazza signed a seven-year, $91 million contract with the Mets, making him at the time the highest paid player in baseball history.46 The deal was also lucrative for the Mets; the team attendance topped 2 million fans in each of Piazza’s eight seasons with the team.47

Piazza’s contract provided him with the respect and security that the Dodgers were unwilling to provide48 and he responded, leading his team to the playoffs for the next two years. In 1999 Piazza set a team record with 124 RBIs, and in 2000, he set a team record with an RBI in 15 consecutive games.49 With Piazza’s help, the Mets reached the World Series in 2000 against the New York Yankees. Tensions were high between the two clubs that October, as Piazza had been hit in the head by a Roger Clemens fastball in their last meeting at Yankee Stadium, on July 8.50

Game Two of the World Series was held at Yankee Stadium with Roger Clemens pitching for the Yankees. In the first inning, Piazza fouled off a pitch.51 The splintered barrel of Piazza’s bat went toward Clemens. As Piazza ran toward first base, Clemens picked up the bat and threw it in Piazza’s direction, later claiming that he thought it was the ball.52 Piazza headed toward Clemens yelling, “What is your problem?” but got no response as Clemens asked home-plate umpire Charlie Reliford for a new ball.53 Piazza grounded out on the next pitch. The Mets lost the game and eventually the World Series in five games. In his only World Series, Piazza batted .273 with three runs scored, two doubles, two home runs, and four RBIs.54

While his productivity continued after the 2000 season, Piazza was involved in a number of rumors and controversies during the 2002 and 2003 seasons. In early May 2002 he responded to the New York tabloids that questioned his sexual orientation. Piazza said he was heterosexual. He also said he felt players could accept an openly gay teammate.55 Later that month, Piazza told the New York Times that he had used androstenedione (legal at that time but since banned by baseball as a steroid), for a short time but discontinued its use “when he did not see a drastic change in his muscle mass.”56 In 2003 controversy once again swirled around Piazza as he learned from the media that the club planned to have him take some groundballs at first base in an attempt to move him to a less demanding position.57 While this angered Piazza, he said that “If [Art Howe, Mets manager,] asks me to go out there, I may not be that good, but I’ll go out and do what’s best for the team.”58 Piazza played a total of 69 games at first base for the Mets.

After the 2002 season Piazza represented Major League Baseball during a three-week tour of Europe.59 Visiting London, Berlin, and Rome, Piazza offered hitting and fielding clinics for kids, promoted the Italian Olympic Team, and had an audience with Pope John Paul II, which was meaningful to Piazza due to his strong Roman Catholic faith.60 In 2006 he played for Italy in the World Baseball Classic and coached the team in 2009 and 2013.61

On May 5, 2004, Piazza hit a home run at Shea Stadium against the San Francisco Giants to pass Carlton Fisk as the all-time leader for home runs by a catcher. The home run was number 352 as a catcher and his 363rd overall. Piazza finished his career with 427 home runs, 396 of them as a catcher.62

On January 29, 2005, Piazza and Alicia Rickter were married at St. Jude Catholic Church in Miami.63 As of 2015 they had three children, Nicoletta Veronica (2007), Paulina Sophia (2009), and Marco Vincenzo (2013).

On October 2, 2005, before a crows od 47,718, Piazza played his final game as a Met.64 After being replaced behind the plate late in the game, the man who “turned Shea into his playground”65 was greeted with a tribute from the team and the fans. A teammate, third baseman David Wright, said: “You have to be the man to have a major league baseball game stop for you for a five-minute tribute and then have five or six curtain calls.”66 In his 7½ seasons as a Met, Piazza batted .296 with 220 home runs and 655 RBIs.67 He caught the ceremonial last pitch from Tom Seaver at Shea Stadium on September 28, 2008, and the ceremonial first pitch from Seaver at Citi Field on April 13, 2009. Piazza was inducted into the New York Mets Hall of Fame on September 29, 2013.

Piazza returned to the West Coast for the 2006 season, signing a one-year, $1.25 million contract with the San Diego Padres.68 He had a solid year for the team, batting .283 with 22 home runs and 68 RBIs.69 For the 2007 season he signed a one-year, $8.5 million contract with the Oakland A’s. After a shoulder injury in early May led to an 11-week stay on the disabled list,70 Piazza returned and finished the season with a .275 average, 8 home runs, and 44 RBIs.

On May 20, 2008, Piazza, 39 years old, announced his retirement as a player in a press release issued by his agent, Dan Lozano. The announcement said, “Los Angeles, San Diego, Oakland and Miami – whether it was at home or on the road, you were all so supportive over the years. But I have to say that my time with the Mets wouldn’t have been the same without the greatest fans in the world. One of the hardest moments of my career was walking off the field at Shea Stadium and saying goodbye. My relationship with you made my time in New York the happiest of my career, and for that, I will always be grateful. So today, I walk away with no regrets. I knew this day was coming and over the last two years I started to make my peace with it.”71

During his career, Piazza was often called a defensive liability.72 However, a number of analyses have identified a number of strengths behind the plate. Sean Forman of Baseball Reference made a case for Piazza as one of the best catchers in keeping the ball in front of him.73 In 2013 Max Marchi of Baseball Prospectus said pitch data showed that Piazza was one of the best pitch framers of all time.74 Perhaps the most telling statistic is that Piazza was the number-one catcher for 11 pitching staffs, and 10 of the 11 finished in the top five in earned run average.75 His former Dodger teammate Mike Scioscia might have put it best when he said: “You had to see Mike from the early days to appreciate how far he came. He made himself into a guy who could go out and catch.”76

In Piazza’s first three years of eligibility for the Hall of Fame, starting in 2013, the percentage of votes he received increased from 57.8 percent to 69.9 percent.77 On January 6, 2016, Mike Piazza was elected into the National Baseball Hall of Fame, receiving 83.0 percent of possible votes. 78 Comparing Piazza to the 13 catchers in the Hall of Fame as of 2015, only Mickey Cochrane and Bill Dickey have higher lifetime batting averages than his .308; only Carlton Fisk and Yogi Berra have more hits than his 2,127; and only Berra and Johnny Bench have more RBIs than his 1,335.79 At a press conference the day following his election into the Hall, Piazza, who will wear a Mets cap on his plaque, stated “It’s so rewarding to be recognized by those who cover the sport and know the gravitas of this Hall and the history of the sport. It’s truly a special club.”80

Last revised: January 11, 2016

Other sources

Baer, Susan. “Major-League Romance.” InStyle, July 4, 2005: 270.

Ballard, Chris. “Oakland Athletics,” Sports Illustrated, March 26, 2007: 97-98.

Bamberger, Michael. “The Quiet Slugger Says Goodbye,” Sports Illustrated, June 2, 2008: 17.

Bechtel, Mark, and Jeff Pearlman. “All Seems Forgiven,” Sports Illustrated, September 7, 1998: 72-76.

Bodley, Hal. “Clemens Makes Best of Situation,” USA Today, July 14, 2004: 4C.

Bodley, Hal. “Piazza Shows Flexibility as A’s DH,” USA Today, April 24, 2007: 5C.

Buckley, Steve. “Piazza’s Hard Work Puts Catcher at Top,” Baseball Digest, November 1999: 32-33.

Delgado, Joel. “Mike Piazza Makes His Ballet Debut in Miami, a Hit Man Again,” Newsday (Long Island, New York), May 4, 2013. newsday.com/sports/baseball/mike-piazza-makes-his-ballet-debut-in-miami-a-hit-man-again-1.5193958 Accessed July 22, 2015.

Dicker, Ron. “Catchers Honor One of Their Own,” New York Times, June 19, 2004. nytimes.com/2004/06/19/sports/catchers-honor-one-of-their-own.html. Accessed July 22, 2015.

Esposito, Andy. “Mike Piazza Mets Moments,” New York Mets Inside Pitch, September 2008: 16-17.

Golenbock, Peter. Amazin’ (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2002).

Hermoso, Rafael. “Piazza Puts Big Hurt on Board,” New York Daily News, 2002.

Hiestand, Michael. “Networks Find On-Air Postseason Talent Waiting in Dugouts,” USA Today, October 3, 2005: 15C.

Kiner, Ralph, and Danny Peary. Baseball Forever (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2004).

Lefton, Brad. “You Have to Hand It to Piazza for Keeping a Firm Hold on a Catching Job,” The Sporting News, June 16, 2006: 42.

Libenthal, Larry. Double Blackjack (Lincoln, Nebraska: iUniverse, 2004).

Lowry, Vicky, and Christine Rosa. “The Sexiest Men in Sports,” Sports Illustrated Women, July/August 2002: 72-101.

Lupica, Mike. “From Star to City, Both Sides See the Light,” New York Daily News, 2002.

Marini, Victoria, ed., “Piazza,” New York Daily News, 2002.

“Me and My Bat,” Sports Illustrated, March 25, 2002: 80.

Pond, Alex, and Kevin Ferris. “Kids Ask…,” Sports Illustrated for Kids, May 1994: 24-25.

Reich-Hale, David. “Three Catchers, Two Positions,” New York Mets Inside Pitch, May 2004: 13.

Roberts, Brendan. “3 Questions With Mets Catcher Mike Piazza,” The Sporting News, April 22, 2005: 70.

Rose, Howie, and Phil Pepe. Put It in the Book: A Half-Century of Mets Mania (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2013).

Ross, Alan. Mets Pride (Nashville: Cumberland House Publishing, Inc., 2007).

Sheinin, Dave. “Baseball: Inside Dish.” The Sporting News, August 19, 2002: 14-16.

Urban, Mychael. “Oakland Athletics,” The Sporting News, May 14, 2007: 42.

Verducci, Tom, and David Sabino. “Catch This!” Sports Illustrated, August 21, 2000: 38-43.

Verducci, Tom. “Near, Yet So Far,” Sports Illustrated, September 24, 2001: 36-37.

Wright, Craig. “Piazza, Hall of Fame Catcher,” in Hardball Times Baseball Annual 2009 (Chicago: Acta Sports, 2008), 148-155.

Notes

1 Bruce Herman, New York Mets: Yesterday and Today (Lincolnwood, Illinois: Publications International, 2010), 123.

2 Michael Bamberger, “Like So Many Other New York City Firefighters Who Died on September 11, Mike Carroll Was a Dedicated Athlete and Local Teammate Whose Indomitable Spirit Led Him to Embrace His Final, Heroic Mission, His Young Son Would Find Comfort in the Company…,” Sports Illustrated, December 24, 2001: 106.

3 Mike Piazza and Barry Rozner, “The Game I’ll Never Forget,” Baseball Digest, November/December 2013: 39.

4 John Snyder, Mets Journal (Cincinnati: Clerisy Press, 2011), 275.

5 Herman, New York Mets: Yesterday and Today, 123.

6 Piazza and Rozner, “The Game I’ll Never Forget”: 41.

7 John Rolfe, “Catching the Beat,” Sports Illustrated Kids, June 1995: 35.

8 Veronica Loveday, Great Athletes of Our Time (Great Neck, New York: Great Neck Publishing, 2011), 12.

9 Michael Bamberger, “Playing the Dodger Blues,” Sports Illustrated, May 25, 1998: 34.

10 Rolfe, “Catching the Beat,, 32.

11 Ibid.

12 Kelly Whiteside, “A Piazza with Everything,” Sports Illustrated, July 5, 1993, 13.

13 Ibid.

14 David Ferry, Total Mets (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2012), 327.

15 Mike Piazza and Lonnie Wheeler, Long Shot (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2013), 19.

16 Rolfe, “Catching the Beat,” 34.

17 Whiteside, “A Piazza With Everything”: 14.

18 Ibid.

19 Steve Delsohn, True Blue: The Dramatic History of the Los Angeles Dodgers, Told by the Men Who Lived It (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, Inc., 2001), 238.

20 Duke Snider and Phil Pepe, Few and Chosen: Defining Dodgers’ Greatness Across the Eras (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2006), 11.

21 Andy Esposito, “Catching Greatness,” New York Mets Inside Pitch, August 2004: 9.

22 Ibid.

23 Whiteside, “A Piazza with Everything”: 16.

24 Peter C. Bjarkman, The New York Mets Encyclopedia (New York, NY: Sports Publishing, Inc., 2001), 85.

25 Tim Kurkjian, “Slim Pickings,” Sports Illustrated, March 15, 1993: 34.

26 Bjarkman, The New York Mets Encyclopedia, 85.

27 Piazza and Wheeler, Long Shot (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2013), 90.

28 Rolfe, “Catching the Beat”: 32.

29 Richard Hoffer, “Catch a Rising Star,” Sports Illustrated, May 13, 1996: 76.

30 Larry Granillo, “Wezen-Ball”, Baseball Prospectus, January 7, 2013, baseballprospectus.com/article.php?articleid=12834, accessed July 22, 2015.

31 “National League Wins All-Star Game,” Jet, July 29, 1996: 50.

32 Bamberger, “Playing the Dodger Blues”: 32.

33 Delsohn, True Blue: The Dramatic History of the Los Angeles Dodgers, Told by the Men Who Lived It, 253.

34 Delsohn, True Blue: The Dramatic History of the Los Angeles Dodgers, Told by the Men Who Lived It, 262.

35 Tom Verducci, “Fox in the Hunt,” Sports Illustrated, May 25, 1998: 44.

36 Bamberger, “Playing the Dodger Blues”: 41.

37 Mark Bechtel and Jeff Pearlman, “Diamondhacks,” Sports Illustrated, June 1, 1998: 87.

38 David Ferry, Total Mets, 317.

39 Michael Bamberger, Kevin Cook, and Richard O’Brien, “Golden Mike Award,” Sports Illustrated, November 2, 1998: 38.

40 Joe McDonald, “Mike Piazza Mets Moments,” New York Mets Inside Pitch, September 2008: 16.

41 Howie Karpin, 162-0: Imagine a Mets Perfect Season (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2011), 67.

43 Bechtel and Pearlman, “Diamondhacks”: 87.

44 Jaime C. Harris, “Piazza’s Big $$$$$ Contract Continues to Raise Questions on Race,” New York Amsterdam News, November 5, 1998: 53.

45 Rusty Staub and Phil Pepe, Few and Chosen: Defining Mets Greatness Across the Eras (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2009), 63.

46 Bamberger, Cook, and O’Brien, “Golden Mike Award”: 38.

47 Matthew Silverman, Best Mets (Lanham, Maryland: Taylor Trade Publishing, 2012), 179.

48 Bamberger, Cook, and O’Brien, “Golden Mike Award”: 38.

49 Karpin, 162-0: Imagine a Mets Perfect Season, 66.

50 Tom Verducci, “Going Batty”, Sports Illustrated, November 1, 2000: 102.

51 Verducci, “Going Batty”: 103.

52 Marlon McRae, “Mets, Yanks, Piazza and Clemens Slug It Out in Big Apple Brawl,” New York Amsterdam News, October 26, 2000: 56.

53 Verducci, “Going Batty”: 103.

54 Bjarkman, The New York Mets Encyclopedia, 21.

55 Don Cronin, “Piazza Denies Gay Rumors,” USA Today, May 22, 2002: 1C.

56 Rafael Hermoso and Tyler Kepner, “Steroid Use Becomes a Topic of Discussion in Clubhouses,” New York Times, May 30, 2002, nytimes.com/2002/05/30/sports/baseball-steroid-use-becomes-a-topic-of-discussion-in-clubhouses.html, accessed July 22, 2015.

57 Hal Bodley, “Mets’ Phillips Gets Away from It All,” USA Today, May 13, 2003: 4C.

58 Albert Chen, “First Move,” Sports Illustrated, August 25, 2003: 80.

59 Mark Beech, Richard O’Brien, and Richard Deitsch, “Piazza’s European Vacation,” Sports Illustrated, December 2, 2002: 26.

60 Piazza and Wheeler, Long Shot (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2013), 273.

61 Jon Saraceno, “Baseball Hasn’t Been Easy for Italians to Swallow,” USA Today, March 10, 2006: 6C.

62 Snyder, Mets Journal, 289.

63 Susan Baer, “Major-League Romance,” InStyle, July 4, 2005: 270.

64 McDonald, “Mike Piazza Mets Moments”: 17.

65 Silverman, Best Mets, 29.

66 Alan Ross, Mets Pride (Nashville, Tennessee: Cumberland House Publishing Inc., 2007), 119.

67 Karpin, 162-0: Imagine a Mets Perfect Season, 85.

68 Albert Chen, “SoCal, So Cool,” Sports Illustrated, August 14, 2006: 77.

69 Piazza and Wheeler, Long Shot, 325.

70 Mel Antonen, “Piazza’s Strong Return Might Boost Trade Value,” USA Today, September 26, 2007: 2C.

71 Piazza and Wheeler, Long Shot, 335-336.

72 Wright, “Piazza, Hall of Fame Catcher”: 155.

73 Dan Fox, “Schrodinger’s Bat”, Baseball Prospectus, July 6, 2006, baseballprospectus.com/article.php?articleid=4945, accessed July 22, 2015; Zachary D. Rymer, “What Is Holding Voters Back from Sending Mike Piazza to Hall of Fame?”, MLB Team Stream, January 6, 2015, bleacherreport.com/articles/2320920-what-is-holding-voters-back-from-sending-mike-piazza-to-hall-of-fame, accessed July 22, 2015.

74 Max Marchi, “The Stats Go Marching In,” Baseball Prospectus, May 16, 2013, baseballprospectus.com/article.php?articleid=20928, accessed July 22, 2015.

75 Wright, “Piazza, Hall of Fame Catcher”: 153.

76 Lyle Spencer, “Catcher Mike Piazza Ends an Impressive Career,” Baseball Digest, August 2008: 78.

77 Chuck Hildebrandt and Mike Lynch, “The Retroactive All Star Game Project,” Baseball Research Journal (Phoenix: Society for American Baseball Research, Spring 2015): 11.

78 Bill Francis, “Griffey, Piazza honored by Hall election”, January 6, 2016, http://baseballhall.org/news/griffey-and-piazza-honored-by-hall-of-fame-election, accessed January 10, 2016.

79 Staub and Pepe, Few and Chosen: Defining Mets Greatness Across the Eras, 6.

80 Bill Francis, “Class of 2016 Reflects on Election”, January 7, 2016, accessed January 10, 2016.

Full Name

Michael Joseph Piazza

Born

September 4, 1968 at Norristown, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.