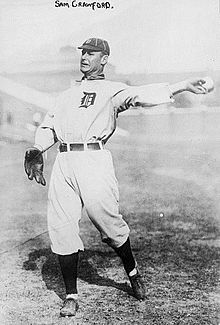

Sam Crawford

Sam Crawford sprung from fertile Midwestern farm soil, and like a storm blowing across his native Nebraska’s prairie swept over the major league baseball landscape for nearly two decades. One of the Deadball Era’s most consistent performers, the powerful Crawford never led his league in slugging percentage, but finished in the top ten in that category every year but one from 1901 to 1915. During that span the left-hander paced the circuit in triples six times, on his way to establishing the career record for three-baggers that has not been eclipsed in the more than 85 years since his historic career came to an end.

Sam Crawford sprung from fertile Midwestern farm soil, and like a storm blowing across his native Nebraska’s prairie swept over the major league baseball landscape for nearly two decades. One of the Deadball Era’s most consistent performers, the powerful Crawford never led his league in slugging percentage, but finished in the top ten in that category every year but one from 1901 to 1915. During that span the left-hander paced the circuit in triples six times, on his way to establishing the career record for three-baggers that has not been eclipsed in the more than 85 years since his historic career came to an end.

Standing an even six feet tall and weighing 190 pounds, Crawford was generally regarded as the strongest hitter of his day. “While we are no sculptor, we believe that if we were and were looking for a model for a statue of a slugger we would choose Sam Crawford for that role,” F.C. Lane of Baseball Magazine wrote in 1916. “Sam has tremendous shoulders and great strength. That strength is so placed in his frame and the weight so balanced that he can get it all behind the drive when he smites a baseball.” Yet Crawford was much more than a one-dimensional slugger. Playing in the era’s cavernous parks, Crawford had to leg out even the longest of his drives. In addition to his 309 career triples, the Nebraskan also holds the record for the most documented inside-the-park home runs in a single season, with 12 in 1901.

Samuel Earl Crawford was born on April 18, 1880, in Wahoo, Nebraska, one of four children of Stephen and Ellen Ann (Blanchard) Crawford. Crawford’s family emigrated from Scotland through Canada. His father fought in the Civil War and used his military pension for a number of commercial ventures, including a general store and real estate speculation. Although Sam was widely regarded as articulate, well-read and eloquent during and particularly after his playing days, he forsook his formal education after the fifth grade to work as an apprentice barber.

Crawford’s trade would make for a great story in later years. National columnist Charles Dryden, in a mock interview with Crawford, had the slugger talk of building his renowned natural strength by “whacking the wind-whipped whiskers of Wahoo.” It became apparent early, though, that Crawford’s attention wasn’t fully trained on the razor’s edge. He began playing baseball at a young age, and quickly showed a talent for the game. Honing his skills playing one old cat with North Ward schoolmates, he joined a team formed by “Snakes” Crawford (likely no relation) which toured eastern Nebraska, challenging town teams for the purse on a daily basis.

The Wahoo contingent “made Cedar Bluffs, Fremont, West Point, Dodge… Schuyler… wherever there was a ball team we challenged them for a game,” Crawford recalled years later. Wahoo won most of those, traveling on a lumber wagon behind a team of horses with a tent and cook stove for subsistence. “We were ballplayers on a trip and loved it.”

Crawford eventually landed with Killian Bros., a local team “who had big league uniforms. We all wanted to play for Killian Brothers and get one of those uniforms,” he wrote. One local crank recalled years later that Crawford earned a suit of clothes from Killian’s mercantile for promising not to smoke. Crawford moved to West Point, Nebraska, in 1898, his first gig drawing a salary to play ball, and then landed jobs barbering and playing baseball in the small Nebraska towns of Wymore and Superior. In the spring of 1899 a pitcher named John McElvaine recommended Crawford to a Chatham, Ontario, club in the Canadian League. The young outfielder tripled in his first game with Chatham, his only safety in four tries, and registered six putouts in left field. He hit .370 in 43 games, moving to Columbus and later Grand Rapids in the Western League after Chatham folded.

Crawford hit .328 with 13 triples and five homers in 60 Western League games that summer, and on August 1 and 2, 1899, played in an exhibition series against the Detroit Wolverines. Batting third and playing left field, Crawford doubled in the first game and knocked out three singles in the second for manager Tom Loftus. Loftus also tried him out as a pitcher that season, and Crawford split two decisions.

After Grand Rapids fell out of the pennant race, Crawford’s contract was sold to Cincinnati, making him the youngest player in the major leagues at age 19. Crawford batted .307 to close the 1899 season, hitting seven triples with a homer in his first 31 major league games. Crawford’s first day in the majors was memorable. The Reds played an unusual Sunday doubleheader in Crawford’s major league debut on September 10, 1899, cracking a pair of singles in four tries against the Cleveland Spiders in game one and walloping his first major league triple and two other safeties off of Louisville’s Bert Cunningham in the nightcap.

From 1899 through 1902, Crawford played 403 games for the Reds, collecting 495 hits, including 60 triples, 56 doubles, and 27 home runs. After batting just .260 in 1900, his first full season in the majors, Crawford put together one of his most successful major league seasons in 1901, batting .330 with a major league-leading 16 home runs and 104 RBI, tied for third best in the NL. In 1902 he maintained a .333 average, second best in the league, and smacked a co-league-high 22 triples. Oddly, Crawford hit only three home runs that season, and just 18 doubles, one of five times during his career that he ended a season with more triples than doubles.

After the 1902 campaign, Crawford jumped his contract with the Cincinnati Reds and signed with the Detroit Tigers of the American League. Crawford immediately became a fixture in the Tiger outfield, appearing in 137 or more games every year for the next 13 years, during which he batted better than .300 eight times. Crawford’s main defensive position was right field, except for 1907 through 1909, when he manned center and the Tigers won three consecutive pennants. Contemporary reports suggest that Crawford was considered a fairly good outfielder. Although he never led the league in assists, Crawford consistently threw out between 16 and 24 baserunners each season from 1900 to 1907. Though not a particularly fast runner, Crawford also covered the outfield terrain more than adequately, and consistently ranked among the league leaders in putouts, although he never led the league in that category.

Of course, Crawford’s stardom owed itself not to his fielding, but his slugging, and it was here that he distinguished himself with the Tigers, becoming one of the sport’s acknowledged longball threats. Like Frank Baker, Crawford eschewed the “scientific” approach to hitting advocated by other luminaries of the game. Put quite simply, Crawford believed that hitting success was simply a matter of seeing the ball and hitting it very hard. “My idea of batting is a thing that should be done unconsciously,” he once explained. “If you get to studying it too much, to see just what fraction of a second you must swing to meet a curved ball, the chances are you will miss it altogether.”

Employing this pared-down philosophy, Crawford became a steady run producer for the Tigers. He ranked among the American League’s top ten in RBI every year from 1903 to 1915, and paced the circuit in 1910, 1914, and 1915 (tied with teammate Bobby Veach). During that 13-year span he led the league in triples five times, extra base hits four times, and doubles, home runs and runs scored once each. Despite his slugging, Crawford was a consistent contact hitter. Batter strikeout totals were not recorded in the American League until 1913, but in that season Crawford struck out only 28 times in 609 at bats, less than half as often as the average AL batter. For a top slugger, he also seldom walked, particularly during his prime. From 1903 to 1910, Crawford drew no more than 50 walks in any season.

During his first three seasons with the Tigers, Crawford was undisputedly the team’s best player, but the disappointing Tigers twice lost more games than they won. Things began to change in 1906, with the emergence of the brash young Southerner Ty Cobb, who by 1907 had propelled the Tigers to the first of three consecutive American League pennants, permanently supplanted Crawford as the team’s best player, and made for himself a slew of enemies within the clubhouse, including the normally easygoing Crawford. Cobb “came up with an antagonistic attitude, which in his mind turned any little razzing into a life-or-death struggle,” Crawford recounted for Lawrence Ritter in The Glory of their Times years later. “He came up from the South, you know, and he was still fighting the Civil War. As far as he was concerned, we were all damn Yankees before he even met us.”

Despite, or perhaps because of, his disagreements with Cobb, Crawford remained one of the game’s most respected figures, admired for his honesty, intelligence, and endurance. “[Crawford] is a man of most exemplary habits, remarkable disposition, and is an example that it would be well for any man in any profession to follow,” Detroit owner Frank Navin wrote in 1915. “He has always been a gentleman on and off the field. I have never had any occasion to worry in the least about his condition.”

From the close of the 1909 Series until Crawford’s departure in 1917, Detroit slipped from serious contention. The Tigers finished within 10 games of first only two times, in 1915 and 1916. Crawford continued to produce at a furious clip through most of that time, though, leading the league in triples in 1910 and 1913-15. He batted over .310 every year from 1910-14.

Crawford’s major league career ended almost as suddenly as it began. After productive seasons in 1915 (.798 OPS with a league-leading 112 RBI) and 1916 (.760 OPS in just 100 games), he limped to a .173 batting average and a .473 OPS in 104 at bats in 1917 before retiring from the major leagues.

Crawford didn’t go quietly. He was released from his contract in 1917 after two years of complaining about his meager salary and Cobb’s individualistic style of play, two nearly-constant sore points with Crawford since Cobb began stealing headlines and drawing a larger salary a decade earlier. Like so many players whose days in the majors were finished, Crawford migrated west, settling in Peco, California, and closing his professional career with four productive seasons with the Los Angeles Angels of the Pacific Coast League, leading the league in hits in 1919 and triples in 1920.

When his playing days were completely over, Crawford made a living raising walnuts but also struggled to stay active in the game. He was head baseball coach at USC from 1924-29, posting a 55-33 record and establishing the Trojans as one of the premier college programs in the nation. He became a PCL umpire in 1935, retiring from the post in 1938 after the passing of his wife of 37 years, the former Ada M. Lattin. Crawford remarried widow Mary Blazer in 1943.

In his later years, the gentle slugger known for his quiet swing lived a reclusive existence, immersing himself in literature and philosophy, until re-discovered by Lawrence Ritter in a Baywood Park, California, laundromat. Crawford proved to be one of the most memorable subjects in Ritter’s classic The Glory of Their Times, interspersing memories of Rube Waddell, Dummy Hoy and Walter Johnson with quotes from Robert Ingersoll and George Santayana in his inimitable plain-spoken manner. “No, I don’t have a telephone,” he explained. “If I had a lot of money I wouldn’t have one. I never was for telephones. Just don’t like them, that’s all. Anybody wants to talk to you, they can come to see you. I do have a television over there–it was a gift–but I never turn it on. I’d rather read a book.”

Crawford’s relationship with Cobb remained complicated throughout their lives. The two partially reconciled at Harry Heilmann‘s funeral near Detroit in 1951, and many consider Cobb’s campaign on his former outfield-mate’s behalf as a primary factor in Crawford’s induction as a member of the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1957. Yet Cobb complained for the remainder of his days about Crawford’s role in the hazing the Georgia Peach endured in 1905 and 1906. Crawford, in turn, was anxious to lay blame for the tension in the Tiger clubhouse at Cobb’s feet. As he told Ritter, “We weren’t cannibals or heathens. We were all ballplayers together, trying to get along. Every rookie gets a little hazing, but most of them just take it and laugh. Cobb took it the wrong way.”

Sam Crawford died at age 88 on June 16, 1968, in Hollywood Community Hospital, following a stroke. On the day Crawford died, the college program he had brought to prominence, USC, won its fifth national championship. He was survived by his widow and two children from his first marriage, and was buried in Inglewood Park Cemetery in Inglewood, California.

Note

This biography originally appeared in David Jones, ed., Deadball Stars of the American League (Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, Inc., 2006).

Sources

For this biography, the author used a number of contemporary sources, especially those found in the subject’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

Full Name

Samuel Earl Crawford

Born

April 18, 1880 at Wahoo, NE (USA)

Died

June 15, 1968 at Hollywood, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.