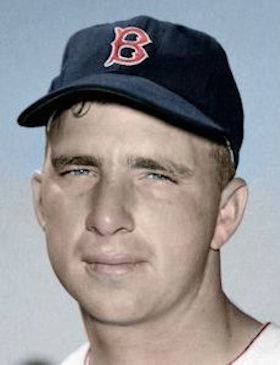

Moose Morton

Guy “Moose” Morton Jr. made his major-league debut with the Red Sox on September 17, 1954. It was the only day he appeared in a big-league box score.

Guy “Moose” Morton Jr. made his major-league debut with the Red Sox on September 17, 1954. It was the only day he appeared in a big-league box score.

His father, Guy Morton — the “Alabama Blossom” — was a right-handed pitcher in the majors for 11 years (1914-1924) with the Cleveland Indians, overcoming a 1-13 first year to end up with a 98-86 career mark and a lifetime 3.13 earned run average. He played seven more seasons in the minor leagues, in the Southern Association and the Piedmont League, right through the 1931 season.

Guy Morton Jr., the only son of Guy and Edna Morton, was born on November 4, 1930, in Tuscaloosa. Guy Sr. died on October 18, 1934, in Sheffield, Alabama, just a few months after he had turned 41. Guy’s son was not quite four years old at the time. He later told author Richard Tellis, “The country was in a depression then, and the South had been in a depression since the Civil War. So after my father died, my mother went to work at a museum at the University of Alabama while I went to live with my grandparents about two miles outside Caledonia, Mississippi, just across the border from Vernon, Alabama. I remember wearing my little baseball uniform while I went out in the fields picking cotton.”1

Morton also remembered his father tossing tennis balls to him when he was 3, as he swung the bat. When he was 11, his mother remarried, to Vaughn Shirley, who worked in a defense plant and later owned a grocery store in Mobile. When he was 13, he moved in with them. He’d already begun playing ball and was on a town team at age 12.

He had heard stories about his father, though, one of which he recounted: “It has been said that only two men ever threw a ball so hard that you could hear it from the dugout. Those two it is said was [sic] Walter Johnson and Guy Morton.”2

He attended Murphy High School in Mobile for two years and made the freshman team as a pitcher under Coach C. P. Newdome. In 1945, when he was still 13, his American Legion team won the Alabama state championship. As a sophomore, he says he was named most outstanding player and some of the scouts began to pay attention.3 He had reportedly also thrown a no-hitter when pitching for the semipro championship of Alabama – but lost the game because of the errors of teammates.4

He graduated from high school in Tuscaloosa in 1948, after his stepfather bought a grocery store and moved the family there.

Guy Morton Jr., grew into a stocky 6-foot-2, 200-pound frame which earned him the nickname “Moose.” He also reported the nicknames “Hoss” and “Salty.” Guy started as a pitcher, but it was his bat that caught the eye of the scouts. He remembers visiting the Red Sox at Fenway in late 1949 and hitting nine of the 10 batting practice pitches he was thrown over the Wall in left.

Becoming a catcher seemed to offer the best route of progress in the game. He said he’d lost the occasional game while pitching high school and semipro ball, and figured if he was losing at that level, “there wasn’t a chance I’d ever become a big league pitcher…So I shifted to catching.”5 He’d gone to a tryout at Branson, Missouri, and showed up with catcher’s gear he’d brought along. His arm was a little stiff and so “I told ‘em that they must have the position down wrong because I was a catcher.” He said he “had been reading in the papers and magazines that catchers were might scarce so I thought that with me having a stiff arm, if I tried out for a catcher, I might stand a better chance.”6 He’d also hurt his shoulder playing football.

Getting to Fenway Park came after finishing his freshman year at the University of Alabama, which he attended on scholarship. He signed a Red Sox contract proffered him by scout Johnny Murphy, which included a $6,000 bonus.

Morton was assigned to the Marion (Ohio) Red Sox in the Class-D Ohio-Indiana League. He appeared in 46 games and hit for a .264 average. He drove in 21 runs. His first base hit as a professional capped a remarkable introduction to the game. Here’s how he told the story:

I got in Marion about twenty hours later with some 1200 miles under my belt, from Boston. Some stockholder met me in Columbus, Ohio, raced me back to Marion as the club was leaving for Zanesville, Ohio at 1:00 PM. We wheeled into the park at 12:45…

I walked in the park and stuck out my hand to meet the manager and he said, “Boy, you gonna have to walk faster than that if you gonna play with me.” That was before I even shook hands with him.

He throwed me a cap, two sizes too small, pair of pants cut off at the knees, and a pair of socks with 14 different holes in them.

I got on the bus, which had seen its last years right after the Depression, was introduced around and took my seat on my suitcase in the back of the bus.

We got in Zanesville, Ohio about 5:30 just in time to eat a little and walk to the park.

I dressed and tried to tape up my pants so I wouldn’t look so bad. I walked out on the field and the manager ask me if I was trying to be funny, by having my pants taped up.

I caught batting practice, then took my turn at bat. I just picked up a bat and broke it on the first pitch. It was the leading hitter’s bat as I found out about 1 second later.

I felt pretty blue about then, but I got to pinch hit in the 9th inning and I lined the first pitch back through the box for a single.

That was how I broke into baseball and my first day in baseball.7

Marion placed fourth in the league standings, but won both rounds of the playoffs to emerge the ultimate champion. He homered twice in the playoffs. Morton said this was the year he was first called “Moose.” He also met Jean Carroll, the daughter of a local minister, who lived across the street from where Morton and other players stayed in Marion. Jean and Guy married the following year, at Thanksgiving time.

He played a full season of Class-D baseball in 1950 for the Kinston (North Carolina) Eagles in the Coastal Plain League. In 120 games, he batted .270. Kinston also finished fourth, and won the first round of that league’s playoffs, but was swept in the finals. Right after he got married, he was called to duty with the National Guard as the war in Korea heated up. He was put to work training new recruits, but got in some time playing for the Army base team at Camp Atterbury, Indiana, a team he remembered as having some very good ballplayers, including a few who played in the majors either before or afterward. His service as a platoon sergeant concluded in August 1952.

He’d missed two seasons of pro ball, but returned to the University of Alabama (as he had done in prior offseasons) to keep working toward a degree in physical education. No longer a teenager, the still-young Morton was bumped up to Class B and played 87 games in the Piedmont League for the Roanoke Ro-Sox in 1953, batting .302. After Roanoke disbanded, he was transferred to the Class-A Eastern League Albany Senators, with whom he played in 35 games. There he struggled with the pitching, batting .225.

He trained with the Boston club at Sarasota in the spring of 1954, but then was placed with the Greensboro (North Carolina) Patriots in the Class-B Carolina League. Everything came together nicely. He was the league MVP. He hit a league-leading .348 for manager Eddie Popowski and drove in a league-leading 120 runs. He homered 32 times. One of them, on the road, was a deep drive. He told Richard Tellis, “Ted Williams and I are the only ones to ever hit one over the flagpole in center field in Birmingham.”8

He looked like a true prospect and got a late September call-up. He traveled to Baltimore to meet the Boston Red Sox, getting there two days before they arrived from Chicago on September 14. As it happened, he was assigned the locker next to Ted Williams. He saw the Sox drop two games to the Orioles, and then traveled to Washington.

On September 17, the Red Sox were playing the Senators and were down 4-0 after just two innings. The two teams and the Detroit Tigers were all bunched together, fighting for fourth place. In the third inning, after Ted Lepcio hit a leadoff double and Milt Bolling struck out, manager Lou Boudreau sent Morton to the plate to bat for pitcher Frank Sullivan. “I remember going up,” he told Tellis. “I had a lot of confidence. I wasn’t scared. It was just another time at bat. I was well schooled and had done this before. I just didn’t do it….I saw the ball well, and I had good cuts.” Facing lefty Dean Stone, Morton struck out on three straight pitches. “I swung at them all — one, two, three. I think the last one was a slider above the belt. I was a high-ball hitter, and I swung over it. I didn’t feel anything particularly about it. It was just another day’s work. I had struck out before.” It turned out to be his one and only at-bat in the majors. The final score was 8-0.

There were still six innings remaining in the game, but Russ Kemmerer took over mound duties and Morton was out of the game. All he remembers from the rest of the game was heading out to the bullpen to warm up pitchers. “It was dark down in that bullpen and these guys are throwing ninety to ninety-five miles an hour and it was scary. In those days, you didn’t wear masks or shin guards to warm up pitchers, or they’d think you were a sissy.”9

By the time he had reached the Red Sox, he might have fared better had he pursued pitching. The Sox had adequate catching.

After the season, he returned to Tuscaloosa and to college. Morton spent five more years in minor league baseball before he decided to hang up his spikes.

In the spring of 1955 he trained at Sarasota again, and experienced an unusual injury – suffering a broken nose when hit by his own foul ball. It was just a slight fracture.10 He was assigned to the Montgomery Rebels. He had an average season (.263, 10 homers) in the Single-A South Atlantic League, and the Red Sox traded him to Washington early in February 1956 (he was on a Louisville contract and traded to the Chattanooga Lookouts, a Senators affiliate).11

Morton caught three years for Chattanooga, 1956-58, his best year being 1957. (He pitched in four games for them in 1956, and played some at third base, shortstop, and right field.) He began 1959 with the Lookouts, too, but in late May was traded to the Atlanta Crackers. He started strong, hitting three grand slams over the course of 17 days, and after the third switching from catcher to pitcher in the game against Shreveport.12 The year 1959 was his last in baseball.

He earned his bachelor’s degree and then a master’s in education from the University of Alabama, with a minor in history. He did later postgraduate work at Ashland University, Bowling Green University, and the University of Akron.

He had worked for a while as a high school coach in Alabama. Moving to Ohio, while teaching at junior high, he started a little church in his own home, did a little street-corner preaching, and was invited to fill in at a church in Wooster, Ohio. He said he had first become a Christian during basic training in 1951. Though he never attended seminary, he became a Southern Baptist pastor and followed that calling for 55 years—first in Wooster, then Lorain and Vermilion. In 2001 he was president of the State Convention of Baptists after three terms in the vice presidency.

He started boys’ baseball leagues in Alabama, and again in Ohio, and a girls’ softball league in Wooster, where he also served for two years as chairman of the March of Dimes.13

He was elected to the Wayne County Christian Hall of Fame, the Tuscaloosa High School Hall of Fame (1972), Most Valuable Player of the Carolina League in 1954, Southern League All-Star Team in 1957, and four other All-Star teams, and was the Alabama High School All-Star Baseball Coach.”14 He was later named the “all-time catcher” of the Carolina League, with Johnny Bench named to its second team – quite an honor.

“Baseball is the greatest game of all,” he said, “but serving God is the real major leagues.”15

Guy and Jean Morton had three children, a son named Guy, who became a minister, and two daughters, Vicki Lynn and Valerie Dawn, and 10 grandchildren.

Guy Morton Jr. died on May 11, 2014, in Lorain, Ohio, and is buried in Vermilion.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Morton’s player file and player questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, Rod Nelson of SABR’s Scouts Committee, Bill Lee’s Baseball Necrology website, and the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 Richard Tellis, Once Around the Bases (Chicago: Triumph Books, 1998), 167.

2 Typewritten recollection in Guy Morton player file at the Hall of Fame.

3 Almost all the information about Morton’s formative years and much of the other material in this article comes from the Richard Tellis book, an invaluable source in writing this biography. This book is highly recommended, and a good source of further information and some fascinating narrative and characterizations of teammates from Morton himself.

4 Joe Cashman, “Sox Rookie Quit Mound for Mask,” Boston Daily Record, February 23, 1954: 40.

5 Ibid.

6 Handwritten memoir titled “How I Broke into Pro-Baseball,” found in Morton’s Hall of Fame player file.

7 Ibid.

8 Tellis, 171.

9 Ibid., 173.

10 United Press, “Red Sox Rookie Breaks Own Nose,” undated, unattributed 1955 newspaper clipping in Morton’s Hall of Fame player file.

11 Associated Press, “Morton Is Traded to Chattanooga with Norwood,” Greensboro Record, February 9, 1956: 35.

12 Hugh Schutte, “Barons Nip Chicks, Retain Loop Lead; Vols Rap Bears,” Huntsville Times, June 10, 1959: 19.

13 Much of the information on Morton’s later life came from his obituary, “Rev. Guy Morton, Jr., 83, Vermilion,” The Daily Record (Wooster, Ohio), May 13, 2014.

14 “Rev. Guy Morton, Jr.,” The Morning Journal (Vermilion, Ohio), May 13, 2014.

15 Tellis, 177.

Full Name

Guy Morton

Born

November 4, 1930 at Tuscaloosa, AL (USA)

Died

May 11, 2014 at Lorain, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.