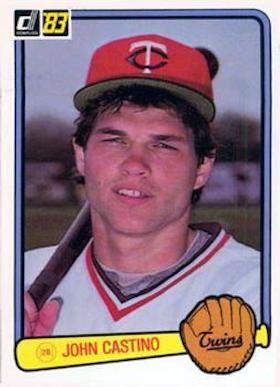

John Castino

In 1979, the Minnesota Twins’ third baseman, 24-year-old John Castino, emerged as the American League’s co-Rookie of the Year. His fielding prowess drew comparisons to some of the all-time great glove men at that position, including Brooks Robinson and Billy Cox. But Castino’s career was derailed by a congenital back defect that became a chronic injury. Just five years later he was out of the majors.

In 1979, the Minnesota Twins’ third baseman, 24-year-old John Castino, emerged as the American League’s co-Rookie of the Year. His fielding prowess drew comparisons to some of the all-time great glove men at that position, including Brooks Robinson and Billy Cox. But Castino’s career was derailed by a congenital back defect that became a chronic injury. Just five years later he was out of the majors.

John Anthony Castino was born on October 23, 1954, in Evanston (Illinois) Hospital, the fourth of nine children of Charles and Mary Castino. His father, the vice-president of a tool company, raised his family in prestigious Kenilworth, an affluent North Shore suburb of Chicago. He grew up with a love for sports, especially basketball, “because it required speed” — and possibly because his dad, a 6-foot-2 inch former basketball player at St. George High School (in Evanston) and Loyola University Chicago, may have influenced him.

When not playing sports or going to school, Castino enjoyed working at his grandfather’s business. “I learned then and there that I had a strong interest for business,” which would help him in later life. In the fall of 1969, Castino entered New Trier East High School, a school with a grand reputation for its performing arts, academics, and having three Illinois High School Hall of Fame athletic coaches: Eugene “Chick” Cichowski, John Schneiter, and Ron Klein. “Three great coaches who couldn’t have been more different,” Castino said. “Cichowski was a hard-charging rough guy who drove and drove. Things had to be his way, which was the right way. Schneiter was more cerebral and laid back. He didn’t yell. He motivated through comments, would laugh, and was a good listener. Klein treated me like a son. He knew I was a free-spirited teenager who wanted to win. He taught fundamentals. I didn’t like to practice, but Klein knew I wanted to play and win. He understood me.”

Basketball, not baseball, was the only varsity team Castino made during his sophomore year. He played a reserve role on an excellent New Trier East basketball team. The Indians won the regional and sectional championships to advance to the Illinois Sweet 16. In the Super-Sectionals (first round of the field of 16), before 6,454 fans at Northwestern’s McGaw Hall, the Indians trailed Oak Lawn by 19 at halftime. Castino watched the first half from the bench and believed he could make a difference. “I told Coach Schneiter that I wanted to play.” The coach put him in, and “at the beginning of the second half, John Castino, a 5-8 sophomore, injected fire into the Indians attack,” wrote a Chicago Sun-Times sportswriter. The Indians were able to cut the Oak Lawn lead to six, but could not pull off the win.1

Two years later, in 1973, Castino had become the team’s starting point guard. New Trier East returned to the Super-Sectionals, and once again the Indians fell behind by a large margin in the early going. However, this time they came back and won. They also won their quarterfinal and semifinal games to advance to the Illinois state championship game. which they lost to Chicago Hirsch High School, a team that featured future NBA player Rickey Green. In the fall of his senior year, Castino played his only season on the school’s football team. In his first game he scored two touchdowns and booted a pair of extra points. He went on to win All-Conference honors while leading the Indians to a 6-0-1 record and a conference championship.

In the spring of 1973, Castino’s senior baseball season was not impressive. “I was hitting only .250 with a few home runs,” he recalled. “On the last day of the season, I went 7-for-8 with two home runs against Proviso East. Had I not done that, I would have been a .250 hitter.” Surprising as it may seem, the Indians baseball team, with future major league players Castino and Ross Baumgarten, plus slugging Dave Hall (who played three years in the Expos farm system), finished just a little better than mediocre. 2

Castino hoped he could play both baseball and basketball in college. Florida Southern offered a dual athletic scholarship, and so did Rollins College in Winter Park, Florida. “I went to Rollins because it was a chance to play basketball for Ed Jucker,” who had coached two national championship teams at the University of Cincinnati, Castino explained. “Also, I liked the baseball coach—Boyd Coffee. But it was basketball that sold me on Rollins.” Castino worked hard to become the sixth man of the team before the start of the freshman season. He looked forward to playing in a road game at Northwestern University, near his hometown. “I was excited about the chance to play before family and friends.” But the chance never came about. Before the start of the season, Castino broke his hand in an off-court incident, sidelining him for the entire season. “I was something of a rowdy. Very wild might be more accurate. I liked the bars; I liked to party. I did a lot of things that I’m not proud of, things I wouldn’t talk about publicly.”3

Castino never got the chance to play for Jucker or even in a single college basketball game. He turned his focus to baseball, although he was unsure which position he would play. He didn’t really care, but he had pitched and played both second and third in high school. Coach Coffee put him in left field, “and I guess I was good at it. I could run down fly balls.”4 At the start of his collegiate baseball career, Castino had no thought about playing the game professionally. “I just played baseball for fun.” But soon he had other ideas. “I felt the competition wasn’t much better than in high school, except the guys were a bit stronger and could throw a bit faster. I said I could go to the next level. Everyone laughed at me for saying this.” But nobody was laughing when during his freshman season he went 2-for-4 against Twins pitching ace Bert Blyleven in a practice game at Tinker Field.

Before the start of Castino’s junior season, Rollins lost its starting third baseman for the season through injury. That’s when Coach Coffee decided to move Castino to third base, where he impressed a lot of people. “I made a few diving catches.” He also made All-American and attracted the attention of the Minnesota Twins. When asked about his star third baseman, Coffee guaranteed the Twins that Castino would be a major league player. “I was eligible for the draft in my junior year because I was 21,”5 and the Twins selected Castino in the third round of the 1976 draft. “(Twins scout) Angelo Giuliani came to my house (in Kenilworth) to sign me. He spoke fluent Italian, and thinking my dad was from Italy, he spoke Italian to him. My dad told him he did not speak the language.”6

After signing, Castino was assigned to Wisconsin Rapids, the Twins’ Class A affiliate. “From the time I signed, I told them I thought second would be my best position, because I didn’t think I’d have enough power for third,”7 said Castino. When he reported to his first professional team, however, he was placed at third base. His first pro season was a success; he hit .286/.387/.433 with six homers and 41 RBIs in 65 games.

During spring training before the 1977 season, Castino had a spiritual breakthrough when teammate Steve Benson invited him to chapel services. Castino initially declined the invitation, but Benson persisted until Castino agreed. “I heard a lot of good things,” Castino remembered. “The Bible offered answers to a lot of questions about the way I was living my life. I asked Christ to come into my life that day.”8 He began the season at Double-A Orlando, but after posting low numbers of .189/.260/.279, was demoted to Visalia, California (high Class A). Castino disliked the time he spent in Minnesota’s farm system. He hated “the grind and long road trips . . . Other than the games, it was difficult.”9

In 1978 Castino went back to Orlando and enjoyed a good season. He hit a respectable .275/.321/.413, with 11 home runs and 63 RBIs. But it was his glove work that earned him a spot on the Sporting News All-Minor Leagues Fielding team as well as a spot on the Southern League All-Star roster.

Slated to play the 1979 season with the Triple-A Toledo Mud Hens, Castino made the Twins roster instead, mostly because of starting third baseman Mike Cubbage’s back spasms. Platooning with Cubbage at third, Castino received his first starting assignment in the season’s fourth game. He collected his first big-league hit, an RBI double against Frank Tanana in the top of the fifth to break a scoreless tie.

In what proved to be a pleasant surprise, Castino became Minnesota’s starting third baseman early in the season when “Cubbage caught the flu.”10 The rookie quickly established himself by going 24-for-85 with 19 RBIs. Gene Mauch said he hadn’t been concerned about Castino’s play in the field, but rather his hitting. “I thought he’d be lucky if he hit .250.”11

Not only did he please the organization with unexpected hitting strength, his fielding was sensational. His admirers were legion. “Just when you think you’ve seen him make his best play, he makes another one,” said Mauch. “I could think of only two other third basemen I’ve seen who could make those plays—Brooks Robinson and Billy Cox.”12 “It’s a great feeling for a pitcher to have a defensive player like that performing behind you,” said Twins hurler Jerry Koosman. “Sometimes during a game I want to stop and applaud some of the plays he makes.”13 In addition to Mauch, a sportswriter also compared Castino’s impressive defensive work to that of the great Baltimore Oriole. “There’s only one Brooks Robinson,” said Mauch. “But that quick release he has, yes, that reminds me of Brooks Robinson.”14 “Castino looks like he’s going to be an outstanding fielder,” said Brooks Robinson himself. “It looks like he’s one already. He resembles me in many ways. His throwing; his actions.” 15

“That was a real compliment,” Castino said when looking back at his career. “Robinson was a broadcaster for the Orioles when I was playing and he used to come down to the field to talk to me. He was such a good man; a classic gentleman.” 16

Castino’s finished his rookie season at .285/.331/.397. In the field he was tops among American League third basemen in turning double plays (31), and stood fifth in most assists, fewest errors, and best fielding percentage. For his successful season at the plate and in the field, and for his all-around good effort, he received seven first-place votes among 28 American League sportswriters who voted for the league’s Rookie of the Year. That was enough to tie him for the award with Blue Jays shortstop Alfredo Griffin. “I was shocked,” Castino added. “I felt I was among the league’s top five rookies, but I didn’t feel I had a chance to win the award, or even share it.”17

“I am very honored and humbled,” said a happy Castino at the time (November 27, 1979). ”It’s a prestigious honor, and I feel I am lucky to have gotten it. I owe a lot of thanks to Gene Mauch and [owner] Calvin Griffith and my teammates.” John’s father, Charles Castino, who was also speaking on behalf of his wife, said, “We’re very proud.” Castino’s high school baseball coach, Ron Klein, concurred. “I always thought John could make it,” he said. “But making Rookie of the Year? You don’t count on that.” 18

Shortly after his successful rookie season, Castino received a contract from Calvin Griffith for the 1980 season. “I received $21,000 during my rookie season and Griffith was offering just $27,500,” said Castino, who mailed an unsigned contract to his boss with a request for $50,000. That didn’t please the Twins owner, who was known for keeping payroll down. “I was at a banquet in Florida where I was being honored as co-Rookie of the Year. [Future NFL star] Cris Collinsworth was also being awarded [for making All-Conference at the University of Florida].” Then Griffith made a loud entrance and bellowed, “Hey Castino! I got you by the balls. If you don’t sign the contract you’ll be out of baseball.” When spring training began, the Twins third baseman was still unsigned. Hoping to get what he wanted, he sat down with his skipper in the manager’s office. “How can I help you, Rook?” asked Mauch. Castino explained the situation. Mauch then picked up the phone and called Griffith. “Give the kid his $50,000,” he said. Griffith agreed, and the deal was done.19

Sportswriters expected Castino to be plagued by the sophomore jinx in 1980. Others hinted that his 1979 batting numbers were inflated, that his rookie season had been a fluke. “I always knew I could hit,” said Castino. “In the beginning of this year I was hitting .220 and they said ‘that’s the real Castino.’ That surprised me because of what I did last year. It’s funny how some people can forget.” His offensive numbers were in fact better in 1980 (.302/.336/.430). He also hit eight more homers (13) and drove in 12 more runs (64). Several scribes were now asking how he avoided the sophomore skid. “I continued to work and play hard,” Castino explained. “I stayed healthy, worked out, and had confidence. Most of all, I had fun. You play better when it’s fun.” It also helped that he played for a team he liked. “I’m very happy with the Twins except for my salary. I found out that Alfredo Griffin is making $87,000 a year, which is substantially more than I get.”

Following the 1980 season, to the chagrin of many, Calvin Griffith began to dismantle his team. Castino understood the situation though. “I felt badly for him. He had no choice but to trade good players. The game was changing, and almost all owners were very wealthy, except for Griffith.” Baseball salaries overall were increasing and so was Castino’s. Learning from his previous experience, he had hired an agent to negotiate his contract this time. The talks went to arbitration, which Castino and his agent won. His 1981 salary would be $210,000.

The 1981 season was a tough one for Castino, the Twins, and for baseball. Besides the players’ strike that idled the season for two months, Gene Mauch’s resignation as the Minnesota manager the previous season affected the team. “He saw the writing on the wall,” said Castino. The 1981 Twins got off to a bad start and team owner Griffith believed it was up to Castino to change the team’s downward spiral. “Castino! Go out here and lead them,” Griffith told him. “I’m not a superstar,” Castino replied. “I’m a scrappy, hardworking ballplayer.”20

Then came September 2, 1981, and a play in the top of the fourth that would change Castino’s career. “I dove for a ball (hit by Dave Winfield) at old Metropolitan Stadium,” Castino remembered, “that forced me to get an X-ray. “The doctors said it showed there was a hairline fracture in the vertebra and that I had been born with a defect called spondylolysis. But it had not surfaced until the injury. This had exacerbated it and made the crack larger.” 21

Despite the injury, Castino continued to play through the next 14 games before the pain forced an end to his season. After the season he underwent a spinal fusion, joining the cracked vertebra to the one above it. He was then fitted then with a body cast for the remainder of the winter, yet he still intended to play in 1982.

I’m a fast healer. That’s why I wanted to have surgery right away . . . so I could be ready for the start of spring training. The body cast was removed shortly before the start of spring training. Coach Coffee saw me in Orlando and was amazed how skinny I was. He worked with me, tried to build me up for the upcoming season. By the second half of spring training, I was playing in games. They held me out of the lineup for a week when the season started.22

Looking back on 1982, Castino feels it was a mistake to play. “I should have taken the year off. Today they never would let a player do that. They didn’t have the physical therapy back then that they have today.”

The 1982 season marked a year of a transition for Castino, from third to second base. “Gary Gaetti was a rookie that season, and he could only play third. They tried him in left field, but he wasn’t good enough. They tried me in left, but I couldn’t cover the ground. I mentioned I had played second base in the past, so they stuck me there and it worked out.” Because he played the season underweight and not at full strength, Castino’s 1982 offensive numbers plunged to .241/.304/.344. The Twins also plunged, to a 102-loss season. “After a tough loss at Detroit, Griffith called the team ‘bums.’ Reporters gathered around my locker in the team clubhouse and asked me what I thought. ‘Look who built the team,’” Castino responded.

“After we returned home Griffith contacted me. ‘Castino, will you come see me at my office?’ he asked me. The Twins owner and second baseman had a long talk. “Afterwards, there were reporters gathered at my locker, wanting to know about our meeting. I told them that I had nothing to say. Griffith and I had our differences, but we got along. We respected each other, always heard one another and always said it the way we really felt.”23

In 1983 Castino got off to the best offensive start of his career. After going 3-for-5 in a June 13 game against the Royals, he was batting .315. Twins manager Billy Gardner “told me that he was going to send me to the All-Star Game. But then I was forced to miss some starts due to my bad back,” which nullified his chance to be on the American League All-Star roster. “Gardner told me he couldn’t send me. I completely understood. I told him, ‘No problem.’” 24

Castino slumped at the plate during the second half of the season, but he still finished with a respectable season, .277/.348/.403 in 142 games. The local sportswriters recognized him as the team’s season MVP for the second time in his career.

On May 7, 1984, the Twins were playing in Anaheim. In the bottom of the eighth Castino reinjured his back while scoring from third on a sacrifice fly. The injury put him on the inactive list. How soon he would be able to return was in question. ”I’m definitely not giving up on (playing) this season,” Castino said. “But the way my back feels right now, I couldn’t play 80 games.”

“I don’t know if it requires surgery, but it (Castino’s back) needs treatment,” said Twins team physician Dr. Harvey O’Phelan. “He’s had almost every conservative treatment except [an injection of enzyme] chymopapain, so his options are limited.”

Castino did his best to stay in shape, although his activities were limited. Trying to take grounders was too painful. He even experienced excruciating pain when playing with his son. Swimming 20 laps twice per day was all he could do. “This has been a real frustrating year,” he said. “It’s not going to be easy if I continue to play and it’s not going to be easy if I retire.” But as the 1984 season moved on, the possibility of retirement loomed as a strong possibility. He tried just about every possible treatment available, but his back did not improve. “I bend forward and backward and I feel movement that is not supposed to be there,” he told a sportswriter. “If I hear of another opportunity, I’ll try it. I’ve gotten hundreds of letters from people suggesting what to do for my back. I’ve tried them all.” 25

He had another spinal fusion performed, but again it was unsuccessful. Under the circumstances, faced with apparently chronic spine issues, John Castino decided to call it a career when the season ended. He was 29 years old.

Following his retirement Castino accepted an offer to work for the Twins. He had three years remaining on his contract, and it was impossible for him to play. “Griffith didn’t insure my contract, and that cost the family a lot of money.” He started his new job as a special assistant to the Twins president and new team owner Carl Pohlad, who had purchased the club during the 1984 season. “At the first team meeting I attended they asked me some personal questions about the players which I refused to answer. I then realized that my heart was still with the players. I resigned after two weeks on the job.” He decided to go back to Rollins College for his senior year, where he posted straight As for the first time in his life to earn his degree in business. “I had always eked through classes and focused on playing sports,” Castino said. “I learned that I could get good grades if I applied myself. I learned you could be good at anything when you put your mind to it.”

After receiving his diploma at age 30, he returned to the Twin Cities and went to work for “good people” at a management company. “I was there for three years when I realized I needed more education for a better understanding of business and to keep up with the businessmen with MBAs from Harvard. So I enrolled at the University of St. Thomas (in St. Paul).” At St. Thomas, Castino continued to excel in the classroom, maintaining a perfect grade point average. “I was on the President’s List at St. Thomas.”

After earning his MBA, he went to work in financial planning. “I like working with numbers,” he said. “I enjoy helping people.” After three years he moved on to a different company, where he stayed for over 20 years. He retired in his late fifties and moved to Florida, where he lives close to his mom and is within an hour’s drive of other family members. “We have a very close-knit family,” he says.

Now living the retirement life in Florida, Castino enjoys his time with family and his three granddaughters. He swims but does not golf like most retirees, because it is too hard on his back. “I’ve had eight back surgeries. I still have back problems. I had a knee replacement, and that was nothing compared to my back problems.”26

Notes

1 Direct Castino quotes from phone interview, author with John Castino, March 17, 2016; Chicago Sun-Times, March 17, 1971.

2 Castino interview, March 17, 2016.

3 Ibid.; John Castino file, HOF library, Cooperstown, NY.

4 Castino interview, March 17, 2016; Casino file, HOF.

5 Castino file, by Bob Fowler, May 12, 1979, HOF.

6 Castino interview, March 17, 2016.

7 Castino file, June 6, 1983, HOF.

8 Ibid., August 16, 1980.

9 Castino interview, March 17, 2016.

10 Ibid.

11 Castino file, December 15, 1979, HOF.

12 Ibid.

13 Ibid.

14 Ibid., by Bob Fowler, May 12, 1979.

15 Ibid., August 3, 1980.

16 Castino interview, March 17, 2016.

17 Castino file, December 15, 1979, HOF.

18 Chicago Tribune, November 27, 1979.

19 Castino interview, March 17, 2016.

20 Preceding material from Castino file, August 3, 1980, HOF.

21 Chicago Tribune, June 27, 2007.

22 Castino file, October 17, 1981, HOF; ibid.; Castino interview, March 17, 2016.

23 Preceding paragraphs based on Castino interview, March 17, 2016

24 Ibid.

25 Preceding paragraphs based on Castino player file, 1984, HOF.

26 All preceding material from Castino interview, March 17, 2016

Full Name

John Anthony Castino

Born

October 23, 1954 at Evanston, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.