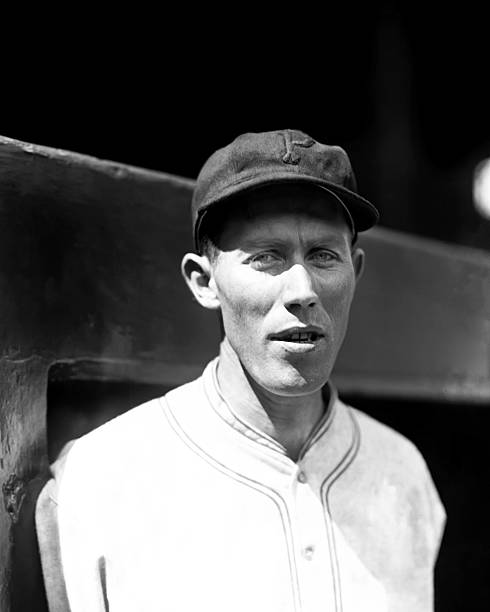

Erv Brame

A hard-throwing right-hander and ball-crushing left-handed slugger, Erv Brame was a genuine double-threat who rode those skills from humble beginnings in rural Tennessee to the major leagues. In parts of five seasons, all with the Pittsburgh Pirates, he batted .306 and also won 52 games, leading the NL with 22 completes games in 1930. Here’s his story.

A hard-throwing right-hander and ball-crushing left-handed slugger, Erv Brame was a genuine double-threat who rode those skills from humble beginnings in rural Tennessee to the major leagues. In parts of five seasons, all with the Pittsburgh Pirates, he batted .306 and also won 52 games, leading the NL with 22 completes games in 1930. Here’s his story.

Ervin Beckham Brame (pronounced with a long a) was born on October 12, 1901, on his family’s farm near Big Rock, an unincorporated hamlet of a few dozen souls in rural Stewart County, located in north-central Tennessee, on the Kentucky border. His parents were Samuel O. and the 15-year younger Mary (Miller) Brame.1 They married in 1889 and welcomed at least eight children to the world between 1890 and 1915. Time has erased many of the details about young Erv’s life. After six years of formal education at Guinn School, he was old enough to join his folks and five elder siblings working the land and tending to the crops in an unforgiving time in an area without electricity or indoor plumbing.

Brame’s foray into Organized Baseball was rocky.2 After earning a reputation as a menacing slugger and overpowering pitcher on local town teams, Brame began his professional career in 1922 as a 20-year-old with a club located about 40 miles from his home, the Hopkinsville (Kentucky) Hoppers of the Class D Kitty League, which was revived after folding in 1916. Statistics from that season are incomplete; however, according to the Louisville Courier-Journal, Brame went 17-4 while also playing in the outfield.3 [Statistics from that era are notably sketchy; The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, for example, listed teammate Mahlon Higby as the league leader in victories with 15; and Brame as the strikeout leader with 135].4 In any case, Brame’s exploits captured the attention of Philadelphia Athletics scout Harry Davis. After the double-threat tossed a four-hitter and fanned 14 to beat Cairo and then whacked two triples as an outfielder to win the game the next day, Davis recognized that the A’s couldn’t wait until the end of the season to make a bid for the player.5 According to sportswriter S.O. Grauley of the Philadelphia Inquirer, Davis wired A’s owner-manager Connie Mack and urged him to secure the player’s rights. The Tall Tactician obliged and purchased Brame for $1,000 in mid-August.6

Mack expected Brame at the A’s spring-training camp in Montgomery, Alabama, in 1923, but the 21-year-old never arrived.7 Apparently having second thoughts about going so far away from home for an uncertain future, Brame broke his contract and played for various independent league clubs in Kentucky, such as Bowling Green (1923) and Glasgow (1924), about 125 miles from Big Rock. Baseball Commissioner Kenesaw Landis cracked down hard on contract jumpers and suspended Brame from O.B.

Landis reinstated Brame two years later, in February 1925, enabling the 23-year-old to report to Mack and the A’s spring camp, which had been relocated to Fort Myers, Florida. Mack didn’t know what to expect from the 6-foot-1, 190-pound Brame who had apparently pitched little in the previous two years in independent leagues, playing in the field and whacking the cover off the ball instead. “I’d rather play in the outfield,” said Brame, “but Mister Mack wants me to pitch.”8 Notwithstanding his lack of experience, Brame made an impression on beat reporter Grauley, who gushed about his “ideal build for a pitcher” and his “fade-away [screwball] which if properly cultivated will make him a winner.”9 He compared Brame’s delivery to that of former A’s standout Jack Coombs, who paced the AL with 31 and 28 wins, respectively in 1910 and 1911, while leading the club to World Series titles. Brame was eventually assigned to Providence in the International League, itself a noteworthy accomplishment and a significant jump from rural independent leagues to one step below the majors. Brame (5-3, 4.66) struggled with wildness, walking almost as many batters (75) as innings pitched (87); he also batted .320 on 16 hits.

Brame was back with Mackmen at spring training in 1926, but was soon dispatched to Anderson, South Carolina, to train with the Reading (Pennsylvania) Keystones, also in the International League. Obtained by Jersey City of the IL in mid-May, Brame tossed a one-hitter to beat the Baltimore Orioles in his debut, on May 20.10 His final unenviable slate (9-21, 3.11) reflected the sixth-place Skeeters’ poor record (72-92). Among his 246 innings were 19 in a distance-going marathon victory, 6-3, on June 5 against Reading’s John Beard.11

Brame signed as a free agent with Jersey City in 1927 and came into his own facing primarily players who had or would have big-league experience. He went 18-9 (3.11 ERA) and tied for the league lead with five shutouts for an awful team (66-100), while cutting his walks down from 127 to 70 in almost the same amount of innings (246 to 243).12 Based on scout Bill Hinchman’s recommendation, the Pittsburgh Pirates, en route to their second pennant in three seasons, purchased Brame from Jersey City in mid-September.13

Brame reported to the Pirates’ spring-training site in Paso Robles, California, in the spring of 1928. Sportswriter Lou Wollen of the Pittsburgh Press described him as “‘loose’ as any member of the mound brigade” and gushed about his “far speedier than average” heater;14 however, the 26-year-old was given little chance to land a spot as a starter on the staff, led by four right-handers who were coming off a season in which they averaged 34 starts and 266 innings: Lee Meadows (19-10), Carmen Hill (22-11), Ray Kremer (19-8), and Burleigh Grimes (19-8), acquired just before camp in a blockbuster trade with the New York Giants. On the other hand, that quartet had an average age of 33.5 years.

Skipper Donie Bush was impressed with Brame’s “cunning” and competitive spirit. According to Wollen, the hurler had an “easy motion on the mound, knows the game, and possesses a brand of ‘stuff’ that should prove tantalizing to hitters.”15 Brame made his big-league debut on April 14, hurling two scoreless innings of relief, yielding two hits in mop-up duty in a 5-0 loss to the Cincinnati Reds. Preseason favorites to capture their third pennant in four years, the Pirates struggled mightily in the early going, and were in sixth place, six games under .500, at the end of May.

Brame, likewise, struggled, clobbered for 12 runs in 16 innings of relief, and was consequently sent in early June to the Indianapolis Indians along with outfielder Adam Comorosky for longtime American Association hurler Bill Burwell on a trial basis. Given a chance to pitch regularly, Brame showed his promise (4-1, 2.29 ERA in 51 innings) and was brought back by the Pirates a month later.16 The Pirates were in desperate need of a productive starter. They had lost Meadows in spring training, Kremer was 4-11 at end of June, and the team saw its pennant hopes wilting.

The Bucs were in sixth place, 13½ games behind the St. Louis Cardinals, when Brame made his first major-league start, tossing a complete game to defeat the New York Giants at Forbes Field in the second game of a twin bill on July 7. Four days later, Brame suffered a “badly bruised finger” on a batted ball hit by Fresco Thompson of the Philadelphia Phillies, and made only two disastrous relief appearances in the next five weeks.17

Brame pitched steadily over the last five weeks of the season, highlighted by his first of eight big-league homers, which gave the Pirates the lead in his eventual distance-going victory against the Phillies at the Baker Bowl in the second game of a doubleheader on September 22.18 The Pirates finished in fourth place, prompting Wollen to declare that the club’s chief weakness “lies in the mound department,” which finished sixth in team ERA (3.95);19 however, the sportswriter pointed to Brame (7-4, 95⅔ innings), despite his bloated 5.04 ERA, as a bright spot for the next season.

Pirates owner Barney Dreyfuss remade the club’s pitching staff for the 1929 season, adding southpaw workhorse Jesse Petty from the Brooklyn Robins and Steve Swetonic, coming off 20 wins with Indianapolis in the AA. Their acquisition relegated Brame to the bullpen, but when Swetonic faltered in the early going, Wollen wrote a strongly opinionated piece in the Press, headlined “Brame Deserves To Start,” on May 27.20

The following day, the elongated Kentuckian, as Brame was often called by sportswriters, tossed a four-hitter to beat the reigning pennant-winning St. Louis Cardinals at Sportsman’s Park, 5-2, to give the Bucs their seventh straight victory and push them into a tie with the Chicago Cubs for first place.

While Brame emerged as a dependable flinger, he also demonstrated his prowess with the bat. Used as a pinch-hitter throughout the season, Brame went on a tear from June 29 to July 31, whacking 13 hits in 26 at-bats, including three doubles and a homer, and drove in nine runs. On July 22 he tossed a complete game to defeat the Brooklyn Robins, 13-3, to move the Bucs 1½ games over the Cubs in the pennant race.

And then the bottom fell out with injuries to Grimes (16-2 at the time) and the team leader, third baseman Pie Traynor. The Pirates lost 21 of their next 32 games, while the heavy-hitting Cubs won 29 of 36 to fashion an insurmountable 14½-game lead on August 27, two days after Bush had been fired and replaced by Jewel Ens.

Brame finished the season by tossing six consecutive complete games, the fourth of which was his first of three career shutouts, a sparkling five-hitter against the Boston Braves on September 21 at Forbes Field. Brame “non-plussed the visitors continually with a streaking fast ball and a fine-breaking curve and had excellent control of his puzzling shafts,” gushed Wollen.21 In his first full season, Brame (16-11) completed 19 games (tied for second in the league), started in 28 of his 37 appearances and logged 229⅔ innings for the runner-up Pirates. His 4.55 ERA was much better than the league average (5.36) in the continued offensive explosion of the game, with major-league games averaging a record 10.4 runs per game. Brame also batted .310 (36-for-116), slugged .500, and knocked in 25 runs.

NL President John Heydler described Brame, along with Bill Walker of the Giants (who led the NL with a 3.09 ERA in his second full season), his teammate Carl Hubbell (18 victories in first season as a starter), and Ray Moss (11-6), in his first full campaign with the Robins, as emerging stars and “young men with as much pitching class as any in major company.”22

Coming off a season in which they scored more runs than any NL team other than the pennant-winning Cubs and had a solid staff (third best team ERA, 4.36), the Pirates were once again expected to challenge for the league crown in 1930. Before spring training, the team suffered its first big blow when “Old Stubblebeard” Grimes was traded; then Lloyd Waner, who batted .353 in 1929, was injured and played only once before June 30.

Brame got off to a good start, rolling off three consecutive complete games, winning twice, in the team’s first eight games. Just as he was finding his rhythm, he received word of his father’s passing, and returned home to his mother. Clobbered by the Giants in his first start back (13 hits and 5 earned runs in 4⅔ innings), Brame rebounded with a six-hitter to beat the Robins, 6-2, then “played the hero role … in a sensational hurling duel,” wrote sportswriter Edward F. Balinger in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, against the Cincinnati Reds on May 18.

His 2-1 victory over Benny Frey improved the Pirates’ record to 14-12, good for fifth place but just a game off the lead in a bunched-up early-season race.23 While scattering nine hits, Brame stunned the Queen City crowd with a “Ruthian smash,” wrote Bucs beat reporter Fred Wertenbach.24 According to the Pittsburgh Press correspondent, the shot was “one of the longest homers ever hit” at Crosley Field, easily clearing the center-field wall, 407 feet from home plate.

Brame waited almost six weeks (until June 26) to win his next game, plagued by a serious “grippe”25 (a case of influenza) and then a stomach injury when he was hit by a batted ball.26 By that time the Pirates were four games under .500 (28-32) and trailed the NL-leading Robins by 10½ games. If anything, Brame was a tough-as-nails country boy, whose Southern drawl endeared him to fans and reporters. While the Pirates fought to play .500 ball, ultimately finishing in fifth place (80-74) to end of streak of 12 consecutive first-division finishes, Brame strung together an impressive stretch from July 30 to September 21, going 10-2 and completing 11 of 12 starts. His eight-hitter on August 18 to defeat the Robins, 4-3, in the Smoky City on Dick Bartell’s walk-off two-run double might best capture the hurler’s resiliency. He pitched despite a bad back and an injured third finger on his left hand, which Balinger reported was “heavily taped and “shielded by a splint.”27

The 1930 campaign will forever be known as the “Year of the Hitter” with numerous offensive records being broken. The NL batted a combined .303, slugged .448, and scored 11.4 runs per game to set new marks; nine batters hit at least .355. Brame himself batted .353 on 41 hits, scored 20 runs, and knocked in 22. On the mound he finished with eye-catching 17-8 slate, led the league with 22 complete games in just 28 starts, and logged 235⅔ innings. On the negative side, opponents batted .305 and slugged .487 against him, and his ERA was 4.70, which when adjusted for parks was still better than average (106 ERA+).28

In December Brame picked up his first and only postseason win, but it wasn’t on the mound. He married Marguerite A. Helming, a local Pittsburgher, an artist, and a former student at Carnegie Tech University (now Carnegie-Mellon University), in a ceremony in Brame’s offseason home in Hopkinsville, Kentucky.29

Skipper Ens knew that if the Pirates had any chance to compete in 1931, his staff would need to rebound from a miserable season. The team ERA had ballooned to 5.24, better only than the Phillies’ hard-to-fathom 6.71 from playing in the bandbox Baker Bowl. The Bucs’ “Big Three” (Kremer 20-6, 5.02; Larry French 17-18, 4.36; and Brame) had each been charged with at least 150 runs (only four other NL hurlers were on that dubious list). [Much to the delight of pitchers, 1931 saw the introduction of a new ball with a cushion-cork pill that had replaced the pure cork center.30 Runs decreased by 2.4 per game and hitting fell by 26 points in the league from 1930.]

Poised for a durable campaign, Brame had undergone a tonsillectomy in the offseason to avoid another debilitating flu attack like the one that hospitalized him in 1930. However, as the Pirates made their way across the country from their camp in Paso Robles, Brame caught yet another serious flu. Limited to a few pinch-hit appearances, he finally debuted on the mound five weeks into the season, on May 18. He lost eight of his first nine decisions, including seven consecutive starts. Six of those were distance-going affairs, including a career-best 10-inning, nine-hit 4-3 loss to the Boston Braves at Forbes Field.

With a record of 13-13 on May 17, the Pirates lost 25 of the next 35 games to derail their season. The club finally woke up, but it was too late to play for anything other than respect. On August 2 Brame “broke into the whitewash orgy,” wrote the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette after the 29-year-old’s five-hitter to defeat the Reds at Crosley Field for the team’s 15th win in its last 20 games.31 It was the Pirates’ fourth straight shutout (French, Kremer, and George Spencer had preceded Brame) and extended the staff’s scoreless-inning streak to 40 innings. (It was stopped the next game at 45 innings against the Cardinals.) Brame shackled the Braves on five hits and tossed his third and final shutout, in his last start of the season, winning 7-0 in the Steel City.

Brame’s final tally wasn’t impressive (9-13, 4.21 ERA in 179⅔ innings); however, he completed 15 of 21 starts. He also connected for 26 hits for a .274 average. The Pirates (75-79) posted their first losing season since 1917, finishing in fifth place again. Brame “hasn’t been in good health since his attack of grippe last spring but he stuck it out,” opined the Pittsburgh Press in a piece published at the end of the season. “So low was the hurler at times members of his family suggested he quit the game for the season.”32 Brame was known for his jovial demeanor, but also took losses to heart. Beat reporter Fred Wertenbach cautioned fans and Pirates brass not to look at Brame’s season as a failure and suggested that a player of his caliber would be “gobbled up by other clubs” if the Bucs harbored any drastic plan to get rid of him.33

Like his mound mates French, Kremer, and Heinie Meine, Brame was an offseason holdout, refusing Dreyfuss’s salary offer, reportedly calling for a 12 percent cut as the Great Depression tightened purse strings across the United States.34 The Smoky City, with its steel, glass, and coal industries, was especially hit hard. Attendance at Forbes Field had dropped from 869,270 in 1927 to an NL-low 260,392 in 1931.

With limited options, the pitchers reported a few days late to camp (except Meine, who held out until late May).35 Slated as a swingman for new skipper George Gibson, who vowed to shake things up in his second stint with the club, Brame held the Cardinals to one run in five innings of relief on April 15 at Sportsman’s Park to win his season debut. It went downhill after that. Knocked out of the box early in two April starts (yielding eight runs in 7⅔ innings), Brame saw little action the rest of the season, making just three starts among his 23 appearances.

From July 3 through August 10, the Pirates were atop the standings, led by a ragtag group of hurlers (eight of whom started at least 10 games). French (18-16) emerged as the ace and one of the league’s most dependable workhorses; Meine (12-9) returned in solid form; rookie Bill Swift (14-10) logged in excess of 200 innings; and Swetonic (11-6) broke out, tying for the league lead with four shutouts. The Pirates were doomed by a 5-22 stretch beginning on July 30 and finished in second place (86-68), four games behind the Cubs. Brame was primarily a spectator from the far end of the bench, making just six relief appearances, yielding 12 earned runs in 10⅓ innings over the last two months of the season.

Given his 3-1 record and 7.41 ERA in 51 innings, no one expected Brame back with the Pirates in 1933. And he wasn’t. In February he was sold outright to the Toronto in the International League.36 Brame spent the next two seasons searching for his “stuff” that batters had long since solved. He was 9-7 (4.59 ERA) with the Leafs, then produced a combined 10-16 record (5.30 ERA) with the Mission (San Francisco) Reds and Portland Beavers in the Pacific Coast League. Brame refused to report to Syracuse upon his trade to the IL club in spring 1935 and returned home to Hopkinsville. He briefly joined the Hoppers in the Kitty League and his two outings brought his career to a full circle and closure. Brame returned to the Kitty League in 1937 as manager of the Paducah Indians, and also occasionally played outfield, but retired before the season was over.

In parts of five big-league seasons, Brame went 52-37, completed 62 of 91 starts among his 142 appearances with a 4.76 ERA in 791⅔ innings. He batted .306 on 121 hits, including 8 home runs and 75 RBIs.

A lifelong Kentuckian, Brame settled on his farm in Hopkinsville. By the end of the 1930s, he had divorced. He enlisted in the service in October 1942 and served 10 months.

On November 22, 1949, Brame died at his home. He was 48 years old and the cause of death was heart disease. He was buried at the Powell cemetery in Lafayette, Kentucky.

Acknowledgments

This biography was edited by Len Levin and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also accessed Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com, SABR.org, The Sporting News archive via Paper of Record, the player’s Hall of Fame file, the online archives for the Pittsburgh Press and Pittsburgh Post-Gazette and other newspapers via Newspapers.com, and Ancestry.com.

Notes

1 Mother’s maiden name is from the player’s death certificate. Commonwealth of Kentucky. [Player’s Hall of Fame file].

2 Research on Erv Brame can be frustrating despite the relatively uncommon last name. Throughout his career in Organized Baseball, sports pages had a field day with his first name. Common spellings were: Ervin, Erv, Erve, Erwin, Irvine, and Irv; the strangest was Victor. His surname was occasionally spelled Braime.

3 “Ervin Brame, Back With Bucs, Is Kentucky Boy,” Louisville Courier-Journal, July 4, 1928: 17.

4 Lloyd Johnson and Miles Wolff, eds., The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, 2nd Ed. (Durham, North Carolina: Baseball America, 2007), 229.

5 “Pitcher Brame of Hoptown Sold For $1,000 to Mack’s Athletics,” Nashville Tennessean, August 14, 1922: 6.

6 S.O. Grauley, “Connie Mack With Art Stokes; Work; Brame Does Act on Hill,” Philadelphia Inquirer,” February 27, 1925: 24.

7 “Jones Wins His First/Phils Seek Boxmen,” Philadelphia Inquirer, March 5, 1923: 10.

8 S.O. Grauley, “Connie Mack Is Pleased With Art Stokes’ Work; Brame Does Act on Hill,” Philadelphia Inquirer, February 27, 1925: 24.

9 Ibid.

10 “Orioles Baffled by Brame’s Offerings as Skeeters Win,” Baltimore Sun, May 21, 1926: 12.

11 Associated Pre4ss, “Jersey City, Reading Play 19 Inning Game,” Tampa Tribune, June 6, 1926: 15.

12 Brame and Leo Mangum of Buffalo each had five shutouts. “Tyson, New Robin, Practically Clinches Intl. Bating Crown,” Brooklyn Eagle, September 18, 1928: 37.

13 Lou Wollen, “Ervin Brame Will Be Added to Pirate Mound Staff,” Pittsburgh Press, March 14, 1928: 18; Associated Press, “Pirates Get Brame,” Asbury Park (New Jersey) Press, September 13, 1927: 17. The deal also included a player to be named later. The Pirates subsequently sent relief pitcher Chester Nichols to Jersey City. AP, “Pirates Release Hurler,” Cincinnati Enquirer, September 16, 1928: 11.

14 Lou Wollen, “Scott Desires Outfield Berth,” Pittsburgh Press, February 24, 1928: 39.

15 Lou Wollen, “Ervin Brame Will Be Added to Pirate Mound Staff.”

16 “Pirates Release Burwell,” Pittsburgh Press, July 2, 1928: 32.

17 Lou Wollen, “Erwin Brame Is Added to Buccaneer Injured List,” Pittsburgh Press, July 12, 1928: 33.

18 Lou Wollen, “Buccaneers Win Double-Header From Philadelphia,” Pittsburgh Press, September 23, 1928: 41.

19 Lou Wollen, “Replacements Are Necessary,” Pittsburgh Press, September 30, 1928: 48.

20 Lou Wollen, “Brame Deserves to Start,” Pittsburgh Press, May 27, 1929: 16.

21 Lou Wollen, “Bucs End Brave Series With 4-0 Victory,” Pittsburgh Press, September 22, 1929: 40.

22 United Press, “Barnard’s Statement Challenged By Heydler,” Pittsburgh Press, October 25, 1929: 59.

23 Edward F. Balinger, “Brame Stars as Bucs Down Reds, 2-1,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, May 19, 1930: 18.

24 Fred Wertenbach, “Pirates-Reds Idle as Rain Calls Game,” Pittsburgh Press, May 19, 1930: 27.

25 “Another Pirate Ill,” Pittsburgh Press,” May 23, 1930: 1.

26 Rd Wertenbach, “Meine in Comeback as Pirates Win,” Pittsburgh Press, June 7, 1930: 11.

27 Edward F. Balinger, “Bucs Rally in Ninth to Defeat Robins, 4-3,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, August 19, 1930: 14.

28 ERA+ is an advanced metric that “takes a player’s ERA and normalizes it across the entire league. It accounts for external factors like ballparks and opponents. It then adjusts, so a score of 100 is league average, and 150 is 50 percent better than the league average.” Adjusted Earned Run Average (ERA+,” MLB.com.m.mlb.com/glossary/advanced-stats/earned-run-average-plus.

29 “Brame of Pirates Weds Local Artist,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, December 23, 1930: 6.

30 Jay Jaffe, “Was MLB’s Juiced Era Actually a Juiced Era?” Deadspin, August 29, 2012. https://deadspin.com/5937432/was-mlbs-juiced-era-actually-a-juiced-ball-era.

31 “Brame Hurls Fourth Straight Shutout,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, August 3, 1931: 13.

32 “Ens Leaves for Series,” Pittsburgh Press, September 29, 1931: 25.

33 Fred Wertenbach, “Buc Hurlers Show Well by Comparison Over Season’s Play,” Pittsburgh Press, October 18, 1931: 23.

34 Edward F. Balinger, “Brame, French, Latest to Join Holdout Ranks,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, January 23, 1932: 16.

35 See Gregory H. Wolf, “Heine Meine,” SABR BioProject. SABR.org. https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/10fba444.

36 Volney Walsh, “Pirates to Stand Pat in Squad of 28 as Brame and Barbee Draw Releases,” Pittsburgh Press, February 15, 1933: 22.

Full Name

Ervin Beckham Brame

Born

October 12, 1901 at Big Rock, TN (USA)

Died

November 22, 1949 at Hopkinsville, KY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.