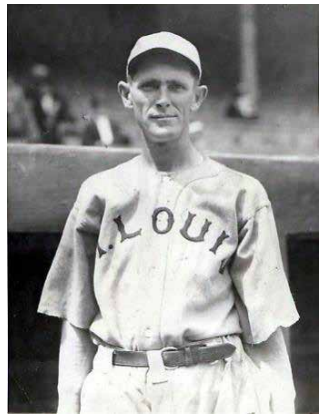

Bill Bailey

Several things are memorable about the career of pitcher Bill Bailey, but unfortunately, almost none of those things would be considered pleasant memories. Most notably, Bailey established a major-league record by experiencing 10 consecutive losing seasons in his 11-year career. Even among the group of pitchers known as 20-game losers, Bailey might be considered something of an overachiever: He was saddled with the 20-loss label once in the Federal League and twice in the minor leagues. It would be easy to overstate Bailey’s struggles as a professional pitcher, but he was largely a victim of dumb luck, having to spend much of his career on poor teams, and pitching in an era where a complete game was the norm.

Several things are memorable about the career of pitcher Bill Bailey, but unfortunately, almost none of those things would be considered pleasant memories. Most notably, Bailey established a major-league record by experiencing 10 consecutive losing seasons in his 11-year career. Even among the group of pitchers known as 20-game losers, Bailey might be considered something of an overachiever: He was saddled with the 20-loss label once in the Federal League and twice in the minor leagues. It would be easy to overstate Bailey’s struggles as a professional pitcher, but he was largely a victim of dumb luck, having to spend much of his career on poor teams, and pitching in an era where a complete game was the norm.

William Franklin Bailey was born in Fort Smith, Arkansas. His parents were William Fuller Bailey of Walker County, Georgia, and the former Leeky Elvira Corn of North Carolina. His mother moved to Walker County before marrying her husband, and the couple came to Fort Smith just prior to Bill Bailey’s birth on April 12, 1888. The elder William F. Bailey died in 1897 and Mrs. Bailey married John U. McLean, a county court clerk, in 1898. The family seems to have moved between Arkansas and Texas a couple of times during Bailey’s childhood. Leeky McLean (who was listed as L.E. McClane on her 1951 death certificate) long outlived her son and was a widow at the time of her death.1

Bailey lived in Houston at the time he entered professional baseball as an 18-year-old with the Beaumont Oilers in 1906.2 Bailey finished the South Texas League season with an 11-9 record, splitting the year between Beaumont and the Austin Senators. For the first couple of years of Bailey’s statistics, there is no indication that the slender left-handed pitcher (5-feet-11 and 165 pounds, according to Baseball-Reference.com) might become known for his hard luck in both the major and minor leagues.

In fact, Bailey was actually a 20-game winner in 1907, finishing 22-11 with Austin before signing with the St. Louis Browns. A typed document in Bailey’s file at the Baseball Hall of Fame indicates that he received what seems like a modest increase in pay upon his promotion; he had been earning $100 per month with Austin and he pulled in $150 per month as a rookie major leaguer. At 19, he was the youngest major-league player that season, and he finished 4-1 with five starts in six games.

After Bailey lost a close game for the Browns against Washington, sportswriter J. Ed Grillo of the Washington Post wrote, “Bill Bailey is a very deliberate young man. He is not in any hurry about delivering the ball to the plate and acts as though he might make a good pitcher though he still lacks considerable experience.”3

The 1908 Browns finished 83-69, but despite an ERA of 3.04, Bailey ended up with only a 3-5 record in 22 games, including 12 starts. Bailey was scheduled to start the 1909 season with the Pueblo Indians. An April 2 column in the Wichita Eagle said that with his acquisition, the Pueblo team was one solid player away from being a contender. However, a separate column in the same issue of the paper announced that the Browns were recalling Bailey to the major leagues.4

By July 1909, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch suggested that Bailey had been pitching to hold on to his job before throwing well in a tough 10-inning loss on July 16.5 Bailey finished the year 9-10 in 32 games despite a 2.44 ERA. The 1909 Browns slid to a 61-89 record and they finished below .500 almost every year until the early 1920s, long after Bailey’s association with the team had ended.

A December 1909 article in the Cincinnati Enquirer expressed mild concern about Bailey’s frailty, but it said that if he kept in shape over the winter, he would likely be a star among American League pitchers. “His fast ball has a jump on it possessed by mighty few lefthanders; his curve ball is a thing of beauty, and last year he developed a move holding the base runners to the sacks, which would play a prominent part in his work,” the article said.6

Reality wasn’t as kind to Bailey. With the hapless Browns in 1910, Bailey had a 3.32 ERA, but opposing teams scored almost as many unearned runs as earned runs against him, and he ended up with only three wins to go with 18 losses. After the season, Bailey’s name was included in some trade talks between St. Louis and Detroit. Ultimately, the teams could not agree to a deal, so Bailey remained on the Browns.7

When Bailey struggled in a few games for the 1911 Browns, the team traded him to the Montgomery Billikens of the Southern Association in exchange for Del Pratt. The deal worked out well for St. Louis; Pratt became the team’s everyday second baseman from 1912 to 1917.

Bailey also did well at Montgomery, finishing 17-6 with a 1.50 ERA and tying a single-game league record in early September by striking out 14 batters.8 The Montgomery squad was previously known as the Climbers, but Bailey was one of five players named Bill, and the Billiken doll was popular in the United States at the time, so the name stuck, at least for that season.9

In 1912, Bailey spent most of the season with the Providence Grays of the International League, going 14-18, and he was hit hard in three major-league appearances with the Browns. He stayed with Providence all year in 1913, improving his won-lost record to 19-15 and lowering his ERA significantly to 3.46.

In 1914, Bailey was with the Grays for most of the season. Earning an 11-8 record by August, Bailey was said to have met with several team executives from the Federal League during a road trip to Buffalo, New York. The Federal League was attempting to compete with the established major leagues by enticing players under contract to “jump” to the new league. Bailey signed with the league’s Baltimore Terrapins.10

It must have been exciting to watch Bailey pitch for Baltimore in 1914. He had a much higher walk rate (4.8 per nine innings) and strikeout rate (9.2 per nine innings) than anyone else in the Baltimore rotation. He had an average ERA (3.08) and finished 7-9 despite pitching 10 complete games in 18 starts. The 1914 Terrapins finished in third place with an 84-70 record.

Bailey’s defection indirectly led to the demotion of young Boston Red Sox pitcher Babe Ruth, the only time in Ruth’s major-league career that he was sent to the minor leagues. Ruth was a promising prospect, but there was not much room on the Boston pitching staff. Red Sox owner Joseph Lannin also owned the Grays, who, unlike the Red Sox, were still in their pennant race. After Bailey jumped to the Federal League and Providence pitcher Red Oldham went to the major leagues, Grays fans were becoming restless. In response, Lannin sent Ruth, the highly publicized rookie, to Providence.11

Bailey returned to the Terrapins for the 1915 season. He didn’t pitch as well as he had the year before, finishing with a 4.63 ERA, but his 6-19 record would have almost certainly been better with another franchise. The Terrapins finished 47-107, scoring almost 100 fewer runs than they had the year before. Bailey was not alone in his pitching misfortune. The previous season’s ace, Jack Quinn, finished with a 9-22 record this time around despite a 3.45 ERA. George Suggs, a 24-game winner the year before, had an 11-17 record with a 4.14 ERA. Even future Hall of Famer Chief Bender, who jumped to the Terrapins for 1915, was 4-16 despite a 3.99 ERA.

Late in the season, Bailey was sent to the Chicago Federals in exchange for Dave Black.12 He had much better luck there, finishing with a 3-1 record and three shutouts in five games. The single loss with Chicago placed Bailey in the 20-loss category for the first time in his professional career. After the Federal League folded in 1915, the Chicago Whales were merged with the Chicago Cubs, but Bailey was released by the Cubs before he appeared with them.13

Bailey ended up pitching for Toledo of the American Association in 1916 and part of 1917, and he appeared rather uneventfully with New Orleans of the Southern Association in late 1917 and early 1918. When the Detroit Tigers called on Bailey in June 1918, he gave up 10 runs in a one-inning relief appearance.14 The Tigers still gave Bailey a few chances as a starting pitcher that year, but combined as a starter or reliever he gave up nearly six earned runs per game, ending his run with Detroit.

In 1919, Bailey was pitching for the Beaumont Oilers when he walked 185 batters, setting a Texas League record.15 He threw 50 games that year. Though his complete-game total is not available, we know that Bailey earned 45 decisions, finishing with a 24-21 won-lost record. He spent the 1920 season with Beaumont again; the team’s nickname changed from the Oilers to the Exporters. He had another strong season, turning in an 18-16 record with a 2.58 ERA.

With the Exporters in 1921, Bailey compiled a 7-10 record with a 2.69 ERA. This was enough to pique the interest of several major-league clubs, and the St. Louis Cardinals obtained him in a June trade for Jakie May (who went on to a long big-league career), a player named George Scott, and cash. The Cardinals also acquired Brooklyn pitcher Jeff Pfeffer around the same time. For much of the year, the Cardinals had relied on heavy offense, so they made the trades to stabilize their pitching staff.16

In Bailey’s debut for the Cardinals, he pitched a 10-inning complete game, but he lost the game on his own throwing error.17 He saw action in 19 games for the 1921 Cardinals, but only six of them were starts. He gave up nearly 12 hits per nine innings, and he finished with a 2-5 won-lost record and a 4.26 ERA.

Bailey’s last major-league season was 1922. He pitched 12 games for the Cardinals, and for the first time in his major-league career, he did not start any games. His 0-2 record gave him a 38-76 major-league record. His career ERA ended up at 3.57. His last season in the big leagues made him the first pitcher with losing records in 10 consecutive seasons. No pitcher had that many consecutive losing seasons until Ron Kline in the 1960s.18

The 1923 season was a rough one for Bailey. He had stints with two teams in separate leagues and he gave up more than five earned runs per nine innings during his time with each team. He was 9-18 for the Houston Buffaloes. Sixteen of Bailey’s losses with Houston were consecutive, tying a consecutive-loss record for Texas League pitchers.19

In August of that year, Bailey was traded to the Omaha Buffaloes of the Western League in exchange for Tex McDonald, a veteran infielder whose last shot at the major leagues had ended with the shutdown of the Federal League eight years earlier.20 Though Bailey’s ERA was still high for Omaha, his luck seems to have improved, as he had an 8-5 record for the team. Still, the five losses with Omaha took him well over the 20-loss threshold for the season.

Bailey pitched for Omaha again in 1924 and 1925. He continued to earn large numbers of decisions, finishing 23-15 and 17-19, respectively. Between Bailey and left-handed pitcher Harvey Harris, Charles Brill of the Daily Oklahoman described Omaha as heading into the 1926 season with the best pitching staff in the Western League.21 However, Bailey was out of baseball before the regular season started because of multiple episodes of intestinal bleeding.22

Bailey had become ill for the first time while Omaha’s team was training in Orange, Texas.23 He was admitted to Baptist Hospital in Houston. Wink Goff, a player on the Houston Buffaloes, donated blood for a lifesaving transfusion.24 On March 30, 1926, one day after Bailey was admitted to the hospital, newspaper reports said that he was near death but that there was still some hope for improvement.25

At least one benefit game was held for Bailey in the Western League.26 His health rallied for several months, but he returned to the hospital that fall and he died on November 2, 1926, just before he was to receive another blood transfusion.27 He was buried at Forest Park Lawndale Cemetery in Houston.

Little is known about Bill Bailey’s personal life. Genealogical research indicates that he married Texas native Elise Villiepique (sometimes listed as Sunshine Elise Villiepique) on January 8, 1924, and that they had a son, Thomas Street Bailey, in 1912. No divorce records could be located, but Villiepique’s 1954 death certificate, which lists Thomas S. Bailey as the informant, indicates that she had lived in Dallas for more than 40 years.28 Villiepique was widowed by Daniel Ruggles, an editor for the Dallas Morning News.29 Thomas Bailey died in 2000.

This biography is included in “20-Game Losers” (SABR, 2017), edited by Bill Nowlin and Emmet R. Nowlin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author made extensive use of the major-league and minor-league statistics at Baseball-Reference.com. Unless otherwise noted, the statistics came from this source.

Notes

1 Certificate of Death: L.E. McClane, Texas Bureau of Vital Statistics. We were unable to determine the occupation of William Fuller Bailey.

2 “Beaumont Here Today,” Houston Post, May 10, 1906: 3.

3 J. Ed Grillo, “Rally Just in Time,” Washington Post, September 26, 1907: 8.

4 “Pueblo Won’t Get Pitcher Bailey,” Wichita Eagle, April 2, 1909: 7.

5 James Crusinberry, “Bailey Wins New Life in Major League,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 17, 1909: 6.

6 “Don’t Quit if First Act Is Poor,” Cincinnati Enquirer, December 26, 1909: 2.

7 “Baseball Flashes From Meetings in New York,” New Castle (Pennsylvania) News, December 15, 1910: 11.

8 “Bill Bailey, Billiken, Equals Strikeout Mark,” Times-Democrat (New Orleans), September 4, 1911: 7.

9 Richard Worth, Baseball Team Names: A Worldwide Dictionary, 1869-2011 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2013), 192.

10 “Bill Bailey Hurdles From Providence Grays to Terrapins,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, August 9, 1914: 25.

11 Robert W. Creamer, Babe: The Legend Comes to Life (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1992), 91, 92.

12 “Bill Bailey Is Traded Off,” Washington Herald, September 18, 1915: 9.

13 “Pitcher Bill Bailey Is Released by Cubs,” St. Louis Star and Times, April 10, 1916: 10.

14 “Tigers Take Bad Beating From Fohls,” Detroit Free Press, June 30, 1918: 17.

15 Individual Records, Texas League, milb.com/content/page.jsp?sid=l109&ymd=20100316&content_id=8811502&vkey=history.

16 “Pfeffer and Bill Bailey Bolster Card Hurling Staff,” Houston Post, July 5, 1921: 11.

17 “Chicago Next Stop of Bucs,” Pittsburgh Press, June 25, 1921.

18 Donald Dewey and Nicholas Acocella, The New Biographical History of Baseball (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2002), 16.

19 Individual Records, Texas League.

20 “Omaha Gets Bill Bailey,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 2, 1923: 25.

21 Charles Brill, “Rates Omaha to Finish One, Two or Three in Race,” Des Moines Register, April 7, 1926: 12.

22 Ibid.

23 “Bill Bailey Dies at Houston Tuesday,” Dallas Morning News, November 3, 1926.

24 “Bailey Won’t Play Anymore,” Mount Carmel News, April 17, 1926.

25 “Bill Bailey, Veteran Major Southpaw, Near Death,” Minneapolis Morning Tribune, March 30, 1926: 14.

26 “Catcher Lowry to Join Demons,” Des Moines Register, June 2, 1926: 9.

27 “Bill Bailey, Colorful Baseball Character, Dies,” Alexandria (Louisiana) Daily Town Talk, November 4, 1926: 4.

28 Certificate of Death: Elise Ruggles, Texas Bureau of Vital Statistics.

29 “Daniel G. Ruggles, 66, Former Editor, Dies,” Dallas Morning News, September 21, 1953.

This biography is included in 20-Game Losers (SABR, 2017), edited by Bill Nowlin, Emmet R. Nowlin. To get your free e-book copy or 50% off the paperback edition, click here.

Full Name

William F. Bailey

Born

April 12, 1888 at Fort Smith, AR (USA)

Died

November 2, 1926 at Houston, TX (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.