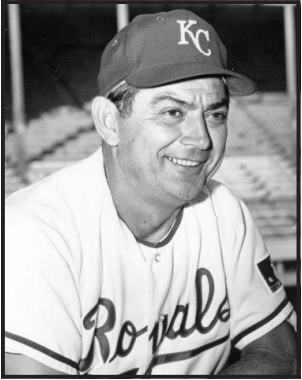

Charlie Metro

After six seasons in the minor leagues, Charlie Metro stepped to the plate at Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis wearing for the first time in a regular-season game the uniform of the Detroit Tigers. It was May 4, 1943, a Tuesday afternoon as America approached its 18th month at war. The next day, the radio news would include reports of the death in an airplane crash in Iceland of Lieut. Gen. Frank M. Andrews, the commander of American forces in Europe. He was the highest ranked American to have died in the conflict and, later, his name would be given to the Air Force base in Maryland from which the president’s airplane flies.

After six seasons in the minor leagues, Charlie Metro stepped to the plate at Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis wearing for the first time in a regular-season game the uniform of the Detroit Tigers. It was May 4, 1943, a Tuesday afternoon as America approached its 18th month at war. The next day, the radio news would include reports of the death in an airplane crash in Iceland of Lieut. Gen. Frank M. Andrews, the commander of American forces in Europe. He was the highest ranked American to have died in the conflict and, later, his name would be given to the Air Force base in Maryland from which the president’s airplane flies.

The weekday afternoon start in the midst of a war perhaps explains an attendance of 647. (To put that figure in context, the 28 names appearing in the box score —26 players and two umpires —equaled 4 percent of the crowd.) For some, the game would be more memorable than for others.

On the mound for the home side was Al Hollingsworth, a veteran left-hander. After Joe Hoover walked to lead off the game, Metro came to the plate in his major-league debut.

“He threw me a fastball for strike one,” Metro later wrote in his memoir. “Dang, I thought, that kind of fastball I can hit, I’ll get him this time. He threw another fastball, and I took it for strike two. Then he came back with another one right down the middle, and I was scared to death. I couldn’t pull the trigger.”

In the dugout, Detroit manager Steve O’Neill had words for the rookie. “Charlie, you can swing,” he said. “You can hit that ball. Swing that bat the next time.”

“Yes, sir,” Metro said.

The manager asked if he was nervous. Metro replied in the affirmative. The manager said, “Well, you won’t be next time.”

In the second inning, Metro again came to the dish. “Hollingsworth threw me a curve ball,” he recalled, “and I ripped it down the left-field line for a double, my first big league hit.”1

Writing after nearly 60 years, Metro can be forgiven for not getting all the facts straight in his memoir. Accounts of the game describe Metro hitting a single, not a double, loading the bases. (He also incorrectly recalled batting leadoff.) Hollingsworth did not get out of the inning, and Metro stroked another single later in the game, going 2-for-4 in his debut as the Tigers hung on for a 4-3 victory over the St. Louis Browns.

Metro played in only 43 more games in 1943, often appearing as a pinch-hitter or pinch-runner. He ended the season with eight singles to show for 40 at-bats (a .200 average). Metro’s statistics would never be worth bragging about. He was an adept fielder who could not hit big-league pitching, not even the watered-down version to be found on rosters through those war years.

At 5-feet-11 and 185 pounds, Metro had the wiry build of a miner —lean enough to work in tight corners, strong enough to wield a pickaxe —and the temperament of a man who knew the bosses were never going to just hand him money. So the figure that obsessed Metro as much as batting average or slugging percentage was the number to be found on his paycheck. His memoir is filled with details about how he fought for every penny from the Tigers and how he was shocked to get a generous offer from Connie Mack of the Philadelphia Athletics, who he had been led to believe was a tightwad. Metro had worked in the mines, had joined the union and helped it fight for better pay, and was in the American League less than a year before he became involved in early discussions about the formation of a players union.

Never shy to speak his mind, the beetle-browed Metro seemed a scowling presence in baseball, especially in his later years after he spent decades in the minors as a manager. As a player in the 1940s, he could have been cast as a member of an all-American platoon fighting the Germans in the thick, tangled forests of Occupied Europe. He would have been the crabby truth-teller, the second-generation immigrant of some dark-featured Eastern European race (Ukrainian in his case), and he would have been a casualty before the third reel.

Even without war, Metro’s birthright was hard work and the possibility of sudden, terrible death. Without baseball he’d have been “toting a lunchpail like most of my friends and worrying when the next explosion would snuff out some more of us.”2 As it was, he worked in the coal mines when not in school and survived a disaster. “I was in a gas explosion that killed several men,” he wrote in his memoir, “and I was lucky enough to come out alive.”3 He considered himself lucky to emerge alive and forever grateful to baseball for lighting a path from the earth’s guts to a greensward on the surface.

Charles Moreskonich was born on April 28, 1918, to Pauline and Metro Moreskonich. His father was an immigrant from Ukraine who labored as a coal miner. Charlie was the first of what would be a brood of nine children. The boy became known as Little Metro after his father, with whom he would tag along to watch weekend ballgames. In time Little Metro became Charlie Metro, a moniker that could fit in a box score without contraction and which became his legal name.

He grew up in Nanty Glo, a town in western Pennsylvania that takes its name from the Welsh term for “brook of coal.” In his memoir, Metro tells of earning $1 by distributing flyers for grocery stores before hitchhiking to New York and getting as far as Gettysburg on the first night, which he spent in an unlocked cell at the police station. He arrived at his sister’s place in New York and eventually made his way by subway to Yankee Stadium, where he was touched on the shoulder by Babe Ruth after the game.

He was still in high school playing for a town team sponsored by the Heisley Coal Company when he jerry-rigged a contraption he felt unique in baseball that would become ubiquitous, the batting tee. Using thick rubber pipe scavenged from the mine, he cut an X across the bottom, nailing the folded strips onto a wooden board as a base. Then he placed an old, taped-up baseball atop the contraption, the better to hit the ball against the side of a house, or an old mattress. Metro later claimed to have begun the paperwork for a patent, which he failed to file for lack of funds to cover the $500 fee.

He first joined his father in the mines the summer after completing his sophomore year of high school. He earned 85 cents for every ton of coal (less deductions to the company store for dynamite and equipment).

In 1937 Metro attended a St. Louis Browns tryout camp with 1,500 other hopefuls at Point Stadium in Johnstown, Pennsylvania. The high-school senior, who hit right and threw right, was one of only 14 players to make the cut. He signed after negotiating a $60 offer up to $100, so he could buy his mother a washing machine. He asked to be paid in $1 bills and when he gave the crumpled money to his mother she wondered if he had stolen it.

Metro’s professional career began in Maryland in 1937 with the Easton Browns of the Class-D Eastern Shore League. A center fielder with good range, a true glove, and an accurate arm, Metro had a weakness –at the plate. He played in only 23 games, hitting a single home run and had a .203 batting average when cut.

The following spring Metro tried out again at the Johnstown camp. This time he was assigned to the Lee Bears of Pennington Gap, Virginia, in the Appalachian League, another Class-D circuit. He nudged his batting average up to a respectable .277.

He kicked around the minors for four more seasons, first with the Mayfield Browns in Kentucky before moving to Texas to play for the Palestine Pals, Texarkana Liners, Texarkana Twins, and the Beaumont Exporters.

In the winter of 1940-41, Metro went to California, where he worked in construction and as a panel inspector at an airplane manufacturer’s. He registered for the peacetime draft and a pilot he befriended offered him five free lessons with the suggestion that he enlist with the American Eagle Squadrons, which was seeing action in Britain against the Germans. In his memoir, Metro claims to have been rejected because of cranial trauma he suffered in the mine explosion.

The manager in Beaumont was Steve O’Neill, 50, a former longtime catcher with the Cleveland Indians. O’Neill had kept his big-league job because of his great defense and strong arm, as he endured seasons of mediocrity at the plate before blossoming as a hitter in his late 20s.

Metro spent the summer of 1942 as a supervisor at the National Fireworks Plant at Viola, Kentucky, which had been converted to make anti-aircraft ammunition. The plant was surrounded by vegetable fields, which soon became overpopulated with rabbits. Metro’s crew, most of them African American, hunted the rabbits at lunchtime for food, though they had to use sticks because they were not permitted to fire rifles so close to the plant. Metro soon joined his men, staying in shape by chasing rabbits on foot.

Metro’s “hustle and versatility” had impressed O’Neill at Beaumont. After O’Neill became the Tigers’ manager, Metro was invited to their spring-training camp at Evansville, Indiana. The Tigers offered $1,800. Metro balked, but soon after accepted an offer of $3,280.

After sparse duty in his rookie campaign, Metro played in 38 games in 1944 (78 at-bats, 15 hits, .192 average) before being released by Detroit. In his memoir, he suggests he was targeted for being in favor of players belonging to a union, having seen the benefits of membership as a miner back home. In any case, he finished the season in Philadelphia, where he suited up for the Athletics in 24 games (4 hits in 40 at-bats). In 1945 Metro played in 65 games for the Athletics with 42 hits in 200 at-bats for a .210 average. He also hit the only three home runs of his major-league career.

One time, Connie Mack called on the light-hitting outfielder for pinch-hitting duty.

“Hit one out of here, son,” Mack instructed.

“Which seat, Mr. Mack?” the cocky outfielder replied.

Metro then struck out on three pitches, returning to the dugout to see the manager using his scorecard to dust off the spot beside him. “This seat, son,” he said.4

On July 4, 1945, the A’s faced the Browns in a holiday doubleheader at Sportsman’s Park. The Mackmen ended a 14-game losing streak by winning 3-2 in the opener. They had a 5-3 lead going into the bottom of the ninth in the second game when the Browns rallied for three runs. The tying and winning runs scored on a single by Pete Gray, the outfielder who had his right arm amputated above the elbow after it became caught in the spokes when he fell off a wagon as a boy. After the game, Mack was furious. “A one-armed guy beat us,” Mack said, slamming his hand down hard on a table. “Maybe we ought to amputate everybody’s arm, if that’s what it takes to win.”5 The manager’s mood was not improved by his leadoff hitter —Metro —going 1-for-10 on the day.

On July 21 Metro watched from the home dugout at Shibe Park as his old team, the Tigers, scored their first run in the seventh inning to tie the game. The teams remained deadlocked as summer daylight gave way to twilight. With two outs in the bottom of the 24th inning, Mack assigned Metro to pinch-hit. He smacked a single to left off Dizzy Trout, who then retired Irv Hall on an infield grounder. The game was then called a 1-1 tie due to darkness.

Metro’s final major-league games came on August 5, 1945, at Shibe Park in Philadelphia, as the Athletics swept a doubleheader from the New York Yankees, 6-3 and 4-3. Metro played left field in both games. At the plate, he hit two singles and scored twice in the opening game. He went 0-for-4 with three strikeouts in the second game. The next day the Japanese city of Hiroshima was devastated by the dropping of an atomic bomb as the war raced to its conclusion.

Metro was sent to the Pacific Coast League, where he played for the Oakland Oaks and Seattle Rainiers over two seasons. In 1947 he became a playing manager in the New York Yankees system. He played outfield full-time for the Bisbee (Arizona) Yanks for a season before holding the same job with the Twin Falls (Idaho) Cowboys, where he handled a promising 20-year-old third-base prospect from San Francisco named Gil McDougald. The skipper led the team in average (.351) and homers (22) in 1948.

In 1950 Metro moved to Alabama to become playing manager of the Montgomery Rebels (later, Grays). Four seasons in Montgomery were followed by managerial posts with the Durham (North Carolina) Bulls, Augusta (Georgia) Tigers, Idaho Falls Russets, Terre Haute (Indiana) Tigers, and Charleston (West Virginia) Senators.

In three seasons with the Vancouver Mounties (1957-59), Metro managed a sharp squad of future major leaguers, including, for 42 games, a young Brooks Robinson. The team got some press after hiring the hot-headed manager by taking out an insurance policy with Lloyd’s of London which specified that the firm would pay all fines after the first $500. The Mounties also created some insurance of their own by giving infielder Johnny (Spider) Jorgensen added duties as a playing coach who would be good cop to Metro’s bad cop. Metro was voted PCL manager of the year for 1957.

In the 1958 season finale in Phoenix, the 40-year-old Metro penciled himself in as starting pitcher and leadoff batter. Jorgensen played catcher, while Vancouver pitcher George Bamberger started at second base before moving to first. The manager went 0-for-2 at the plate and gave up two earned runs in two innings on the mound to take the loss.

Metro handled the Denver Bears for two seasons, guiding them to the American Association pennant in 1960 before becoming, in 1962, one of three men to serve that season as head coach of the Chicago Cubs in the unorthodox and failed College of Coaches experiment. The Cubs finished with a dismal 59-103 record under Metro, El Tappe, and Lou Klein.

After three seasons as chief advance scout for the Chicago White Sox, Metro switched to the St. Louis Cardinals organization as manager of the Tulsa Oilers, where one of the brightest prospects in 1966 was a young left-hander named Steve Carlton. After two years scouting for the Cincinnati Reds, Metro was hired in 1968 as director of player procurement for the expansion Kansas City Royals. The new team’s general manager was Cedric Tallis, who had hired Metro as a manager in Montgomery and Vancouver. Metro was named Royals manager for the team’s sophomore season. It did not go well. A disciplinarian who had been managed by the likes of Connie Mack and Casey Stengel (in Oakland) tried to impose old-school rules on players just beginning to exercise the freedoms associated with the post-Vietnam, Ball Four era. The manager was particularly incensed by the play of Lou Piniella, the 1969 American League rookie of the year. Metro felt Piniella failed to hustle, an unforgivable violation of the manager’s code. He embarrassed the player by pulling him after a fly ball dropped among three fielders in a spring-training game.

“Metro’s managerial virtues were many: intense devotion to the game, special dedication to what are known as ‘the basic fundamentals,’ great energy, long years of experience and widely acknowledged knowledgeability,” Roy Blount, Jr. wrote in Sports Illustrated. “He also proved to be the most fertile innovator to come along in years, introducing mass pregame calisthenics for general loosening, a batting cage in the bullpen for pinch-hitters to warm up in, true-and-false tests for checking out his players’ thinking and —to prevent any kind of satisfaction after a loss —a ban on the traditional postgame cold cuts and pretzels.”6

The players failed to respond. The Royals were 19-33 when Metro was fired as field manager, though he stayed with the Royals until his contract expired at the end of 1971. One of the first acts of his replacement, Bob Lemon, was to restock the postgame buffet.

Metro scouted for the Tigers in 1972 and 1973 before being hired by the fledgling Major League Scouting Bureau as a cross-checker with responsibility for re-evaluating top prospects. After the bureau released him, Los Angeles Dodgers general manager Al Campanis hired Metro as an advance scout and an “eye in the sky” offering advice from the press box. He was on staff when the Dodgers appeared in the World Series in 1977, 1978 (both six-game losses to the Yankees), and 1981, when Tommy Lasorda’s Dodgers avenged the earlier defeats with a six-game triumph over the Yankees, who, incidentally, were managed by Lemon, Metro’s replacement in Kansas City.

In 1982 Metro worked as a coach for Oakland A’s manager Billy Martin. By 1984 he had returned to the Dodgers as a scout, officially retiring the following year to his 15-acre ranch in Colorado, northwest of Arvada, where he continued to work on baseball projects. He raised cattle on the ranch in the 1960s before taking up quarter horses.

Metro died of mesothelioma on March 18, 2011, at Buckingham, Virginia, at age 92. At the time of his death, he was survived by his wife of 69 years, the former Helen Deane Bullock, a “Dixie cupcake” who caught his eye when he was a player at Mayfield. They married on April 3, 1941, in Texarkana, Texas. Metro was also survived by a daughter, three sons, 11 grandchildren, 19 great-grandchildren, two great-great-grandchildren, a sister, and two brothers.

Metro bristled at being described as a player who only got his shot at the major leagues because of depleted wartime rosters.

“They called us ‘wartime ballplayers,’ 4-F’ers, ‘slackers,’ and everything else,” he wrote. “I took offense at being labeled a ‘wartime ballplayer,’ and I still feel that way. We all played like heck. We played our hearts out. … We were all patriots. We had relatives in the military. Most of us tried to get in the military.”7

Notes

1 Charlie Metro with Tom Altherr, Safe by a Mile (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2002), 74.

2 Metro, xiv.

3 Metro, 15.

4 Metro, 85.

5 Metro, 86.

6 Roy Blount, Jr., “Tale of the derailed Metro,” Sports Illustrated, June 22, 1970.

7 Metro, 69.

Full Name

Charles Metro

Born

April 28, 1918 at Nanty Glo, PA (USA)

Died

March 18, 2011 at Buckingham, VA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.