Boze Berger

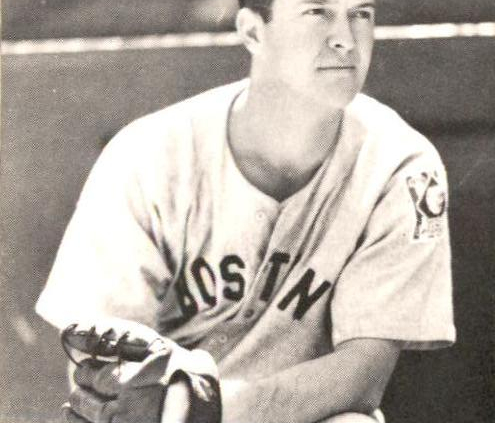

Prospects who don’t fulfill their promise are a dime a dozen throughout baseball history. Boze Berger could be the epitome of that kind of prospect. While his major-league service was not exemplary, Berger had a flexible glove in the field, giving him some value to a few American League teams. After spending three seasons with the Cleveland Indians and two with the Chicago White Sox, Berger capped his big league career with one season on the bench for the 1939 Boston Red Sox. Often described as an athletic, tall, and rangy youngster with a pleasant personality and a sheepish grin, the right-handed Berger went from a star college athlete to highly touted prospect to a career military officer.

Prospects who don’t fulfill their promise are a dime a dozen throughout baseball history. Boze Berger could be the epitome of that kind of prospect. While his major-league service was not exemplary, Berger had a flexible glove in the field, giving him some value to a few American League teams. After spending three seasons with the Cleveland Indians and two with the Chicago White Sox, Berger capped his big league career with one season on the bench for the 1939 Boston Red Sox. Often described as an athletic, tall, and rangy youngster with a pleasant personality and a sheepish grin, the right-handed Berger went from a star college athlete to highly touted prospect to a career military officer.

Louis William Berger, also called “Bozie,” “Bosey,” or “Boze,” was born on May 13, 1910, on an Army post in Baltimore, Maryland, and grew up in Arlington, Virginia.

His father, also Louis Berger, was a career Army man, a noncommissioned officer, who served in France during World War I. Berger’s mother was Mary E. Daywalt of Baltimore. Boze also had a twin sister, Elizabeth.

Berger graduated from McKinley Technical High School in Washington and the University of Maryland, in 1932. At Maryland he was an all-American athlete excelling at baseball, basketball (he was the university’s first All-American basketball player), and football. A star halfback on the football team, he scored two touchdowns in his first varsity game at Yale, forcing a 13-13 tie with the Ivy League school.

University of Maryland athletic director H.C. Byrd said Berger possessed the greatest competitive spirit of any athlete he had seen. In his honor, the university started a Bozie Berger Cup during his rookie year in the major leagues, annually awarded to an outstanding University of Maryland athlete.

A member of the Omicron Delta Kappa fraternity, Berger was the vice president of the Student Government Association and participated in the Army Reserve Officers Training Corps, achieving the cadet ranking of major. After graduating, he held a reserve commission in the Army while he pursued a career in professional baseball.

As the third baseman for the Maryland Terrapins, Berger batted .365 in his senior season and had a .978 fielding percentage, making him a widely sought after prospect coming out of the college ranks. According to Cleveland scout Bill Bradley, Berger had as many as a dozen scouts watching him at a time. He was considered one of the most skillful fielders among college baseball players of the day.

The decision came down to Cleveland or Detroit, but Indians general manager Billy Evans told Berger’s coach that the youngster would have a much better chance of rising quickly to the major-league club, because the Tribe was being rebuilt with young prospects, while the Tigers had a roster populated by veterans. Just before he received his bachelor’s degree in economics, Berger signed with Cleveland for the same salary that Detroit offered. He reported to the team on June 15, 1932, and stayed with the big-league club for a few weeks before being sent to the minors. He appeared in just one game, on August 17. He had one at-bat, a strikeout.

With the exception of that one at-bat, Berger spent his first three seasons in the minors. His first stop was with the Williamsport (Pennsylvania) Grays of the Class B New York-Pennsylvania League during the summer of 1932. In 21 games, playing mostly third base and some at second and shortstop, Berger batted .298 in 84 at-bats, hitting one home run and driving in 10 runs. He impressed Cleveland enough that he earned a promotion to the New Orleans Pelicans for the following season. He did not fare as well with the Pelicans in the Class A Southern Association, but impressed with his glove by playing every infield position. Berger played in 78 games, but hit only .240 in 225 at-bats with two home runs, 31 RBIs, 12 doubles, four triples, and three stolen bases.

In 1934, Fordham baseball coach Art Devlin, a veteran of John McGraw’s New York Giants teams, told a sportswriter that Berger was the best fielder he’d seen since he coached Frank Frisch at Fordham, and thought he would hit over .300 in his first year with Cleveland. Cleveland general manager Billy Evans was also excited by the young Berger, saying he was a “can’t miss” star in waiting. Yet observers said Berger had a lot of trouble hitting curveballs as a result of standing too close to the plate and holding his hands too close to his body, not allowing himself to reach for balls breaking on the outside corner of the plate.

Berger also impressed Cleveland manager Walter Johnson during spring training in 1934. He used the young prospect throughout much of the exhibition season. Second base was a spot of uncertainty for the Indians. Odell Hale, the leading candidate for the position, was a natural third baseman, while Berger showed proficiency at all infield positions. Ultimately Johnson felt the young Berger needed more seasoning in New Orleans before he could join the big-league club, and Hale won the starting second-base job. Berger was sent back to New Orleans with instructions for Pelicans manager Larry Gilbert to rectify his inability to hit the curveball.

At New Orleans, Berger showed enough improvement at the plate at earn Most Valuable Player honors. He batted .313 for the pennant- and Dixie Series-winning Pelicans. He had a .471 slugging percentage and tied for the league lead in base hits (190). Hitting in the second spot in the lineup, he drove in 94 runs, scored 105 times, and hit 42 doubles, 10 triples, and 11 home runs. He had 11 stolen bases. He also proved a standout defensively at second base, recording 990 chances, one short of the league record, and participated in 112 double plays.

Sportswriter Sam Murphy said that Berger was able to improve by simply watching other batters in the league. He developed a crouch and began hitting the curves swooping toward him. When opposing pitchers adjusted by throwing fastballs high and inside, forcing Berger out of his crouch, he went into a half-crouch and found that he was successfully able to hit anything hurled at him, Murphy wrote.

Berger earned another cup of coffee with the big-league club at the end of the 1934 season, but never entered a game. However Johnson announced that Berger would make the 1935 team either at second or at third.

The spot opened for Berger when Cleveland moved Odell Hale to third base. Before the season began, Berger was told he would probably also see action in right field because of his strong right arm. “For combined strength and accuracy of throwing, probably no man in the American League outshines him,” Gordon Cobbledick wrote in the Cleveland Plain Dealer on April 8, 1935. Johnson had high hopes for the rookie; he even told a sportswriter in January that Berger held the destiny of the 1935 Indians in his own hands. As for Berger, he said, “I know it is a great responsibility, but I really haven’t given thought to it. I’m going to do the best I can and if that isn’t good enough it’ll be just too bad for me.”

Pelicans manager Larry Gilbert told Cobbledick on February 25, “In the field he can do anything any second baseman can do. He’s so good that if he hits .260 or .270 he will be a valuable man, but I believe he’ll do better than that.” Sportswriter Charles L. Dufour agreed, writing in the New Orleans Item that Berger was one of the greatest baseball heroes in the history of the Pelicans. “If second base strength is all you need to be a pennant winner you’ve got it,” he wrote.

As the starting second baseman for the 1935 Indians, Berger played 124 games and committed 27 errors, more than average for the era, but he handled many more chances that most at his position. He was, perhaps, an above-average defensive player. He played in 124 games, but might have played in more if he had swung the bat better. He recorded a .258 batting average, only 5 home runs, and 43 RBIs. According to Billy Evans, big-league pitchers were finding they could get Berger with the curveball.

Manager Johnson told Boston sportswriter John Drohan in May, “The trouble with Berger is that he’s trying too hard. But he may snap out of it anytime.” Johnson had big expectations for the Indians, but they could muster only an 82-71 third-place finish.

Berger lost his starting job to rookie Roy Hughes after hurting his arm while making a fast underhanded throw. Hughes played 40 games at second. In retrospect, wrote Gordon Cobbledick in the Cleveland Plain Dealer in March 1936, “Much – undoubtedly too much – was expected of Berger in spring training last year. He looked pitifully weak at times, but never allowed his weakness to get him down.”

During the 1935-1936 offseason, Berger spent time at his Rosslyn, Virginia, home resting his injured arms and coaching the Fort Myer Army post basketball team. He was confident going into the 1936 season that he could win back the starting job at second. He had signed a new contract that included a salary increase.

But Hughes was handed the starting job. Berger appeared in only 28 games. He had 52 at-bats and connected for only nine base hits, for a measly .173 batting average.

In the offseason the Indians placed Berger on waivers, and just as the 1937 season began, the Chicago White Sox picked him up. While replacing an injured Tony Piet at third for 40 games, Berger once again failed to impress with his fielding as he committed 10 errors. In 130 at-bats, he hit 5 home runs, drove in 13 runs, and batted .238 with a .322 on-base percentage.

At the start of the 1938 season, Berger got his chance to prove himself with the White Sox after starting shortstop Luke Appling was injured. Berger accumulated the most plate appearances in his career that season with 470 at-bats and 43 walks while filling in mostly at second base and shortstop. But he hit only .217 and made 21 errors in 67 games at shortstop and 15 errors in 42 games at second base. He hit three home runs and had 36 RBIs.

On December 21, 1938, the White Sox traded Berger to the Boston Red Sox for infielder Eric McNair. McNair went on to have a successful season, playing mostly third base for the White Sox and batting .324 with 82 RBIs. Berger meanwhile spent most of the season on the bench. He accumulated only 30 at-bats in 20 games, rapping out nine hits for a token .300 batting average. He played 10 games at shortstop, five games at third base, and two at second base.

With highly touted rookie Jim Tabor getting most of the action at third base, Berger was “wearing the seat of his pants thin” by riding the bench, according to Boston sportswriter Vic Stout. He had appeared in just two games without any at-bats when presented with an opportunity in June. Tabor was briefly benched by manager Joe Cronin. Berger was so excited by the opportunity that an hour before Red Sox batting practice, he went out to the diamond, stood at third, and had grounders batted to him. That day against the Washington Senators, Berger went 1-for-2 with a double, a fly out, and a sacrifice bunt. His second-inning RBI became the game-winner as Lefty Grove pitched a 3-0 shutout. Tabor retained his job however and had a successful rookie season.

For Berger, 1939 was his last major-league season. On December 26, the Brooklyn Dodgers purchased his contract from the Red Sox for the $7,500 waiver price. The Dodgers signed him as a utility infielder, and he went to spring training in 1940 with hopes of making the big-league club. But he faced a big obstacle: a young, up-and-coming rookie by the name of Pee Wee Reese. The underweight shortstop asked Berger how he could quickly put on weight. Berger took Reese to dinner and instructed the rookie to eat everything the experienced veteran ate. Reese was sick for three days.

Before Opening Day, Berger was sent to the Dodgers’ Montreal farm club in the International League, where he spent the entire season. He played in 134 games, and hit only.232 in 435 at-bats, with 25 doubles, 6 home runs, and 50 RBIs.

Before the 1941 season, the New York Yankees acquired Berger from the Dodgers for first baseman Jack Graham. That season, he played for four minor-league teams: Newark, Kansas City, Toledo, and Seattle. At Kansas City and Toledo in the International League, he batted only .209 in 91 at-bats. While playing for Seattle, Berger was able to contribute to the team’s Pacific Coast League championship, hitting .246 in 130 at-bats with one home run and 17 RBIs. It was during this season that Berger married the former Mary Jean Lowe.

Although he signed on with the International League’s Baltimore Orioles as a player/coach for 1942, Berger was unable to assume those duties. The United States entered World War II after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, and Berger was activated as an Army officer. He reported for duty on February 3, 1942. He went on to serve for 20 years, first as an Army officer, then with the Air Force. He retired as a lieutenant colonel.

Berger had been looking forward to playing for and coaching the Orioles, since he was from the area, but he was also eager to serve his country. “Baseball was a lot of fun but it wasn’t a very steady job,” he told the County Advertiser of Montgomery County, Maryland, in 1983. “With a wife and child on the way, I wanted something a little more secure.” Berger never played professional baseball at any level again, although he did participate in a Service All-Star game in 1942.

During World War II, Berger served in China. After the war, he became a United Nations observer. During the Korean War, he was the commander of Iwakuni Air Force Base in Japan. Later he commanded Bolling Air Force Base in Washington. He was awarded the Bronze Star for his service. After retiring from the Air Force in 1962, Berger worked as the director of building services at the University of Maryland until 1974.

Boze Berger died of a heart attack on November 3, 1992. He was 82 years old. He is buried in Arlington National Cemetery, outside Washington. Shortly after his death, his wife, Mary Jean, wrote in a note found in his Hall of Fame file that if he could live his life all over again, he would do it the exact same way – only he would be a switch-hitter.

Sources

Most statistical information about Berger’s career comes from www.retrosheet.org, www.baseball-reference.com, and www.baseball-almanac.com

Berger’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame library contains unidentified clippings.

Graham, Dillon. “Berger Coaches Army Cagers; Says Arm Is in Good Shape.” Associated Press, January 25, 1936.

Cobbledick, Gordon. “Extra Man Role May Aid Berger.” Cleveland Plain Dealer, March 6, 1936.

Cobbledick, Gordon. “Bill Rapp, Who Discovered Ferrell, Tipped Off Indians on Bozo Berger.” Cleveland Plain Dealer, April 1, 1935.

Cobbledick, Gordon. “Berger Draws Praise of Old Nats’ Speeder.” Cleveland Plain Dealer, November 25, 1934.

Cobbledick, Gordon. “Berger “Can’t Miss as Star, Says Evans.” Cleveland Plain Dealer, March 17, 1934.

Cobbledick, Gordon. “Berger Groomed to Play ‘Em Off Wall.” Cleveland Plain Dealer, April 8, 1935.

Cobbledick, Gordon. “Berger Joins Batterymen in 1st Drill.” Cleveland Plain Dealer, February 25, 1935.

Associated Press. “Indians Put Finger on 2d Sacker.” January 10, 1935.

Rossomondo, Bob. “Bosey’s Baseball.” The County Advertiser, Montgomery County, Maryland, July 27, 1983.

Full Name

Louis William Berger

Born

May 13, 1910 at Baltimore, MD (USA)

Died

November 3, 1992 at Bethesda, MD (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.