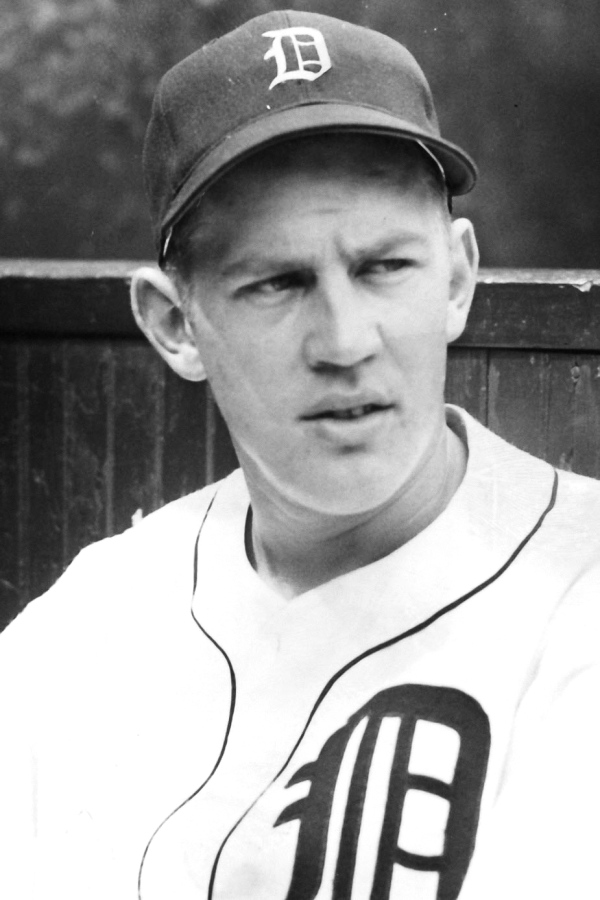

Hank Riebe

Harvey Donald Riebe used to enjoy talking about his years as a big league catcher during the 1940s. He was proud of making it to the majors when the American League and the National League each allowed only 200 players on eight teams. When he first came up with the Detroit Tigers in August 1942, Harv hit .314 in 11 games.

Harvey Donald Riebe used to enjoy talking about his years as a big league catcher during the 1940s. He was proud of making it to the majors when the American League and the National League each allowed only 200 players on eight teams. When he first came up with the Detroit Tigers in August 1942, Harv hit .314 in 11 games.

But as happened to many players of his generation, World War II interrupted and probably hurt his baseball career. Riebe served 39 months in the Army, and he fought in France in 1945. While many big leaguers served as recreation directors or other noncombat jobs and played baseball to entertain the soldiers and sailors, Harvey earned two Purple Hearts for his military experience.

Because the timing of his career, the national impact of World War II, and Detroit’s shifting needs for catchers, Riebe never became a regular. But he did team up with such outstanding pitchers as Hal Newhouser, Dizzy Trout and Virgil Trucks, as well as with good backstops like George “Birdie” Tebbetts and Bob Swift.

Riebe’s stats were not impressive. In 61 games spread over four seasons with the Tigers, he got only 137 official at-bats and hit .212. Although he never slugged a home run in a big league game, Harv fondly remembered driving a Bob Feller fastball over the fence during a 1946 exhibition game in Clearwater, Florida.

“In 1939, prior to signing a contract,” Riebe explained in a 1995 interview, “I attended a game at old League Park in Cleveland on a high school ticket. It was Cleveland versus Detroit, and I was in the bleachers with a buddy. Rudy York was shagging fly balls just below us in left field. I yelled at him to throw us a ball. He did just that, and the next spring I was in Lakeland, Florida, with York and Tommy Bridges, Hank Greenberg, Charlie Gehringer, Bobo Newsom, ‘Schoolboy’ Rowe, and many more. Talk about a dream come true! York was a catcher, first sacker, and outfielder. That spring training he gave me his catcher’s mitt and said, ‘Here, son, I don’t like catching.’”

Harvey’s story began near Cleveland, where the youngest son of Frank and Elsie Riebe was born on October 10, 1921. Harv, older brothers Roland, Mel and Bill, and his sister, Nadine, grew up in a working class family. For fun the Riebe kids played a number of childhood games and sandlot sports-notably baseball and basketball. Harv’s brother Mel, a 5-foot-11 guard, later played six years of pro basketball (1944-49), averaging 12.9 points per game. Frank Riebe never played pro ball, but he had a real talent for statistics. As early as he can remember, Harv played baseball. On Saturdays he would skip chores and sneak off with his older brothers. The Riebes and their friends would play all day on a diamond they made not far from their homes.

Harv graduated from Euclid Shore High School in April 1939, near the end of the Great Depression. Even though he starred in basketball for two seasons, he considered baseball his favorite sport. Detroit, Cincinnati, and Cleveland scouted the personable, talented, hard-throwing catcher. After finishing the sandlot season with Fisher Food Juniors, Harv signed with the Tigers for a bonus. “$250 was a lot of money to me in those days,” Riebe recalled, with a laugh. “Cleveland and Cincinnati offered me only $125.”

When Riebe was in high school, his brothers and his buddies called him Harv, short for Harvey. But more often then not, the reader sees “Hank” when looking up Riebe in baseball reference works, which often employ nicknames used in a player’s early years or by a few sportswriters. In Riebe’s case, he got the nickname from a sportswriter when he first began playing pro ball. But the name disappeared when he made the majors in 1942. A half-dozen of his former teammates, in interviews and correspondence with the author, never used Hank to refer to Riebe. Harvey never referred to himself as Hank in six years of knowing the author. Mary Riebe, widow of the former Euclid star, said in 2003 that she never knew anyone, except fans writing for autographs in later years, use the name Hank for her husband.

In late June Detroit sent the stocky 5-foot-9-1/2 165-pounder to Beaumont, the Tigers’ top farm team. But the Texas League was very competitive, and Harv did not get into a game. After three weeks, he was shipped to Alexandria, Louisiana, of the Class D Evangeline League. There he caught three games and took his cuts 10 times, collecting two singles. “I’ll never forget playing for Alexandria down in Louisiana Cajun country,” he recollected. “I caught Virgil Trucks in my first night game. The lighting was bad enough, but the bugs flying around your mask were terrible!”

After that first brief pro season, Riebe came on strong. The right-handed hitter spent most of 1940 with fifth-place Muskegon of the Class C Michigan State League. Catching and playing some outfield, Harv averaged a fine .348 in 89 games – including 28 doubles, three triples, five home runs, and 42 RBIs. In August Detroit moved the Euclid native to Henderson of the Class C East Texas League. Harv hit .325 in the club’s last 13 games, slugging two doubles and driving in three runs. “Detroit really moved players around a lot,” Riebe reminisced in 1996. “In 1941 I skipped around considerably. I started with Detroit in Lakeland for spring training. They sent me to Beaumont for about three weeks, but I never played there. I went to Winston-Salem, North Carolina, in the Piedmont League. Then I went back up to Muskegon, and from there I went to Beaumont, all in the same year!” Riebe made solid contributions on Detroit’s farms, averaging .289 in Winston-Salem, .243 in Muskegon, and .198 in Beaumont.

In 1942 Riebe returned to Beaumont, where he spent most of the year. “Harvey was an outstanding defensive catcher,” recalled teammate Johnny Lipon, himself an excellent infielder. Enjoying a solid season for the first-place Exporters, Riebe averaged .274 and produced 13 doubles, one triple, five round-trippers, and 26 RBIs. The rifle-armed receiver fielded .973, with 53 assists. En route to a 73-81 record and a fifth-place finish in 1942, Detroit called up Riebe and Lipon that August 12. The new rookies became roommates. Riebe took the roster spot of Birdie Tebbetts, who hit .247 in 97 games behind the plate.

Like dozens of other major leaguers, Tebbetts had been drafted during that first wartime season. He left for the Army the day Riebe arrived. Little-known Edward “Dixie” Parsons, who caught 62 contests and batted .197, backed up Birdie. Riebe, who joined the Tigers at Shibe Park in Philadelphia during the club’s “Eastern swing,” made an immediate impact. On August 26, in the second game of a Sunday doubleheader, he caught Hal White, a young righthander who was 12-12 with a 2.91 ERA in 1942.

In his first major league at-bat, with the bases loaded and the Tigers behind, 2-0, Harv slammed Dick Fowler‘s first pitch down the left field line for a two-run double. Just barely fair, the ball bounced off a girder and back into play. The recruit just missed a home run in his first big league at-bat! In his second at-bat, with flychaser Bob Johnson playing Riebe to pull, the Tiger rookie doubled to left center, his normal power alley. Harv went 2-for-4, handled seven chances flawlessly, and clicked with Lipon at shortstop for a double play. Detroit won, 4-2.

In his first appearance in Detroit’s Briggs Stadium, on Labor Day, September 7, Riebe went 4-for-4, all singles. For the rest of the season he caught 11 games and hit .314 in 35 at-bats, a promising beginning for his big league career. He handled all the Tigers’ mound stars, including Newhouser, Trucks, Trout, and Al Benton.

Right after Labor Day, Riebe learned that he had to report to his draft board when the season ended. In mid-October, Uncle Sam placed him on a bigger team: the nation’s military. Harv spent over more than three years in the Army. In fact, Riebe risked his life serving his country. After basic training in Camp McClelland, Alabama, he was assigned to the 66th Infantry Division, the “Black Panthers.” In late 1944 his unit, the 262nd Regiment, shipped overseas and was stationed near Dorchester, England.

Twice SSgt. Riebe nearly lost his life. For those risks in the line of duty he was later awarded two Purple Hearts and the Oak Leaf Cluster. On Christmas Eve in the English Channel, Riebe was one of 2,235 soldiers – mostly of the 264th Regiment – aboard the S.S. Leopoldville, a transport carrying reinforcements, toward the Battle of the Bulge. But a German submarine torpedoed and sank the Leopoldville less than six miles off Cherbourg, France. Riebe survived almost an hour of floating in the icy water before a Coast Guard cutter pulled him out. Rescue boats and crews saved more than 1,400 men. Unfortunately, 763 Americans lost their lives in the worst U.S. troop ship disaster of World War II.

Rejoining the 66th Infantry in Cherbourg, Riebe and his division were assigned to mop up pockets of German resistance around St. Nazaire and Lorient. In the spring of 1945, he was hit in the right shoulder by shrapnel from German artillery. But the Euclid native was able to walk to a field hospital, where surgery was successful. That wound earned him a second Purple Heart.

In September that year the Tigers, led by the heroics of slugging first baseman Hank Greenberg and southpaw Hal Newhouser, won the American league pennant over the Washington Senators. Detroit went on to defeat the Chicago Cubs in an exciting seven-game World Series. Thousands of soldiers listened to the Fall Classic by radio. “Listening on the radio from a tent in France,” Harv recollected, “I heard my Tigers win that World Series. It was great!”

The former Tiger played some baseball in Europe after the war ended. SSgt. Riebe backstopped the 66th Infantry’s team. Organized in the spring, Harvey’s club defeated several service teams in southern France and later won the championship of the 16th Corps.

Shortly after being mustered out in early 1946, Riebe returned to Euclid. He married his hometown sweetheart, Mary Golinar, on February 19. The next day he reported to Lakeland, Florida, for spring training with the Tigers. For a few weeks it looked like Harv might be Detroit’s third catcher, behind Paul Richards and Bob Swift. But Detroit still had most of the veterans who won the World Series. In the end, manager Steve O’Neill, although high on Riebe, cut him.

Though disappointed, Harv maintained a positive attitude. A tireless worker, he was dedicated to succeeding. Detroit sent him to Buffalo of the International League, then to Dallas of the double-A Texas League. Batting .242 for Dallas, Riebe helped his team finish second and win the league’s playoffs. Dallas won the Dixie Championship by sweeping Southern Association winner Atlanta in four straight games. The Rebels won the title with a 9-7 victory over the Crackers on October 4, 1946. In that contest Riebe slugged a grand slam home run to cap a six-run third inning, giving Dallas a lead that stood up.

Returning to Lakeland in 1947, Riebe again found Detroit’s training camp filled with catchers, including Tebbetts, Swift, and rookie Bill Mathis. Harv played well, for example, going 1-for-2 in a 13-1 thumping of the Phillies on March 11. Riebe began the season in Detroit, with Swift as the regular backstop. But Harv appeared in only eight games, going hitless in seven at-bats. In May new general manager Billy Evans traded Tebbetts to the Boston Red Sox for left-handed-hitting catcher Hal Wagner, who hit .288 for Detroit in 1947.

After the Wagner trade, Riebe was farmed out to Memphis of the Southern Association. Still determined to get back to the big leagues, he performed well for the second-place Chicks, hitting .287 and working smoothly with the pitching staff. His strong ’47 performance helped Riebe return to Detroit. The World War II veteran spent all of the 1948 and 1949 seasons with his favorite club. In 1948, when the Tigers finished fifth (78-76), Bob Swift, who hit .223, called most of the signals.

In November 1948, Detroit acquired left-handed-hitting Aaron Robinson from the White Sox for pitcher Billy Pierce. Robinson batted .269, including 13 homers and 56 RBI. Still, Detroit only climbed one notch to fourth place (87-67) under new skipper Red Rolfe.

Riebe played sparingly in 1948 and 1949, hitting .194 in ’48 (he caught 24 games) and .182 in ’49 (he caught 11 games). Harv fought the biggest challenge that athletes experience when playing off the bench. He couldn’t get enough time behind the plate to hone his catching skills and to get his hitting into a groove. As a result, his skills languished.

During spring training in 1950, Riebe was sold to Toledo of the American Association. In 30 games he averaged .237 before going on the disabled list with a sore back. By then he was discouraged, thinking he no longer had a chance at the big leagues.

Harv left baseball in 1951 and became a purchasing agent for the Cleveland brass and copper company where he had worked in the off-seasons. He served the firm until taking early retirement in 1977. During later years the former catcher particularly enjoyed his family – which now included Bruce and Barbara — golfing, woodworking, and answering fan mail.

Riebe had one regret. He missed qualifying for a baseball pension by 35 days. While riding Detroit’s bench in mid-1949, he learned from a friend that the Boston Braves wanted his services. Under the standard reserve clause, however, Detroit controlled Riebe’s rights. The front office refused to trade him.

“I have nothing but good to say about all the Detroit players,” Riebe said in 1998. “For instance, I got along fine with Birdie Tebbetts. He used to say, ‘You’re a better hitter, but I’m a better catcher!’ Tebbetts would always kid me, ‘Riebe, are you trying to take my job?’ My reply was, ‘Birdie, you better believe it!’”

Riebe was impressed with the big leaguers he met: “I remember shaking in my boots when I caught my first game at Yankee Stadium,” he recalled. “Bill Dickey was catching for the Yanks, and he could tell I was having a hard time picking up the ball from the pitcher. You have to remember that during those years, about 90 percent of the men who went to ballparks would wear white shirts. At Yankee Stadium, the ball was coming out of a sea of white in center field. Dickey saw that. When he came up to bat, he called me aside, turned away from the umpire, and said, ‘The shirts are getting you, huh?’ I said, ‘Yeah.’ He said, in a low voice, ‘ You need to pick up the ball as soon as it leaves the pitcher’s hand.’” Receivers, Riebe explained, are so used to catching a certain pitcher that they usually pick up the ball on the way to home plate: “It took me 8-10 pitches to get used to it, but Dickey was right. That little tip, and many more from other major leaguers, was how we used to learn the tricks of the trade.”

Riebe, who never appeared on a baseball card during his playing days, appeared in a 1995 set issued by Pacific Trading Cards. “‘I had a dream come true 53 years ago when I made it to the major leagues,’ I told the people at Pacific Trading Cards. Now you have made my second dream come true by creating a baseball card for me.’ I feel very fortunate,” the Euclid native observed.

Johnny Lipon wrote, “Harvey Riebe was a good competitor, a fine handler of pitchers, and definitely a winning-type player.” Regarding the effect of the war, Johnny added, “There’s no doubt the war years cut Harvey’s career short.”

“I always liked Harvey Riebe,” Hal Newhouser commented in 1995. “He was a good person with a good sense of humor. He used to warm me up before games and in the bullpen. Harvey could have been at least a good second-line catcher. But Detroit already had Bob Swift. And because of that short right field in Briggs Stadium (315 feet to the overhang), they traded for left-handed batting catchers, Hal Wagner in 1947 and Aaron Robinson in 1949. So Harvey never really had a chance to show his ability.”

Still, Riebe lived his baseball dream five decades ago. Positive, friendly, and witty, he was happy to be an occasional hero. Detroit’s loyal fans liked classy individuals like Riebe. Harv remembered one youth to whom he gave a baseball before a game at Briggs Stadium on June 3, 1949. “I know not one member of our family will ever forget,” the boy’s mother wrote to Riebe, “the thrill of being given a ball from a member of our own Detroit Tigers. I think you know who our favorite ball player is.” “When I put the ball in the boy’s hand,” Harv said, smiling at the memory, “his eyes got as big as saucers. So I kept the letter, and I can still see that youngster’s eyes!

Riebe enjoyed hearing from fans and readers. He replied to every letter or phone call asking for his autograph or for information about baseball during his era. In fact, he kept every fan letter, accumulating several boxes of letters and other items over the years. Writing to a friend on February 27, 2001, Harv expressed it this way: “For me, it’s very rewarding to answer a call that comes or a letter that arrives because someone remembers a game, or whatever, and to know I was a part of it.”

Baseball lost a fine ambassador when the former Euclid star passed away on April 16, 2001. As an athlete and a gentleman, Harvey Riebe symbolized the big leaguers of the Forties: the first-class young men who worked their way up through the minor leagues to play in “The Show,” who joined the service and risked their lives fighting the Nazis or the Japanese, and who returned home and once more gave baseball their best shot.

Sources

Interviews with Harvey Riebe, 1995, 1996, 1997, 1998, 1999, and 2000; Riebe Scrapbooks, in possession of Mrs. Mary Riebe; clippings in Riebe file in the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library; Baseball Encyclopedia (Macmillan Publishing, 1990 edition; “S.S. Leopoldville Disaster, December 24, 1944,” videotape first shown the History Channel, May 2001; Pat Doyle, The Professional Baseball Player Database, version 5.0; interview with Hal Newhouser, 1995, letter from Johnny Lipon, 1995; interview with Hal White, 1996; interview with Red Borom, 1996; interview with Virgil Trucks, 1997.

Full Name

Harvey Donald Riebe

Born

October 10, 1921 at Cleveland, OH (USA)

Died

April 16, 2001 at Cleveland, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.