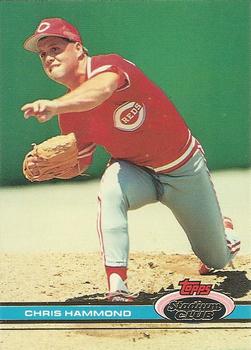

Chris Hammond

Only three pitchers have maintained earned run averages below 1.00 for a full season. Ferdie Schupp did it in 1916. Hall of Famer Dennis Eckersley duplicated the feat in 1990. The third person? Chris Hammond.1 In 2002, he pitched 76 innings and gave up a miniscule eight earned runs, resulting in a 0.95 ERA.

Only three pitchers have maintained earned run averages below 1.00 for a full season. Ferdie Schupp did it in 1916. Hall of Famer Dennis Eckersley duplicated the feat in 1990. The third person? Chris Hammond.1 In 2002, he pitched 76 innings and gave up a miniscule eight earned runs, resulting in a 0.95 ERA.

Making Hammond’s accomplishment even more remarkable is the fact that, four seasons earlier, he had retired from baseball. Going into 2002, he was making a comeback and just wanted to earn a spot on the Atlanta Braves roster so he could share his baseball experiences with his children Andy, Jake, and Alex, who had been too young to enjoy his 1990s tenure. “My wife [Lynne] and I were thinking about different things we could do,” Hammond says, recalling why he returned to baseball. “She’s a great cook, so we were considering opening a restaurant. Then she looked at me and said, ‘The one thing I regret is our kids never saw you pitch in baseball. Never saw you on the field.’”2

That comment sparked Hammond to knock off the rust and see what was left in the tank. After all, he was only 35 years old. He was left-handed, a prized commodity for a pitching staff. He had walked away from baseball, but not because of arm injuries.

As it turned out, he went on to pitch five more years in the big leagues.

Born on January 21, 1966, in Atlanta, Hammond’s baseball beginnings trace to the Little League fields in Vestavia Hills, Alabama. His father Ben, who worked in the insurance business, coached Hammond through elementary school and junior high. Ben may not have known all of the game’s technical details, but he instilled in his son a love for the game.

“He never yelled at us,” Hammond says. “He threw batting practice for days. And, all my friends, everybody on the other team, after the season was like, ‘Chris, I want to be on your team next year.’ We won, and my dad made baseball fun.”

The third of four sons, Chris grew up in an athletic family. His oldest brother, Steve (born in 1957), spent nine years in professional baseball, a right fielder who played 46 games for the Kansas City Royals in 1982. Chris’s youngest brother, Greg (born in 1968), also played professionally, spending four seasons as a catcher in the Cincinnati Reds organization. When Greg was a high school sophomore and Chris a senior, the two were battery-mates. Chris liked working with his younger brother.

“Having a good catcher is always beneficial to building a good pitcher,” Hammond says. “[Greg] could help me with my pitches, give me insight on what they look like.”

Although Chris loved baseball, he didn’t specialize in it. He played in the summer, then enjoyed neighborhood football games in the fall, and basketball in the winter. Mix in some tennis with his best buddy, Stephen Jones, and Hammond was a well-rounded athlete. Comparing this approach to today, Hammond shakes his head.

“The reason I love baseball is because I didn’t play it all the time,” he says. “That’s the one thing missing in today’s generation. There’s no childhood of growing up because travel ball occupies everybody’s weekend. There’s no more playing one or two games on a Saturday, and then going over to somebody’s house for a pool party. I mean, my team and all my friends, after games, we would come back to my house and swim for the rest of the day. And, it’s just a tragedy where baseball is in today’s generation, and it’ll never change.”

Reaching Vestavia Hills High School, Hammond continued playing baseball and playing it well. By his senior year in 1984, he pitched, winning seven games and losing none. He also played left field and hit over .500. His skills and success led him to collegiate baseball and the University of Alabama at Birmingham. After a year, he transferred to Gulf Coast Community College in Panama City, Florida.

“That’s what I tell kids these days,” Hammond says. “It’s not about going to Alabama or Auburn right out of high school. Go to a junior college and build your confidence. I mean, baseball and everything that comes along with it, it’s tough. It’ll chew you up and spit you out if you think it’s all about going to Alabama or wherever, Southern Cal, and playing baseball as a freshman. That’s just what I’ve seen.”

With his 6-foot-1, 190-pound frame, Hammond played in the outfield and was the designated hitter at Gulf Coast, but his occasional pitching attracted the attention of the Cincinnati Reds. “I pitched a few simulated games in the fall, and I pitched one game against South Alabama,” Hammond says.

After one game, a Reds scout approached Hammond and said, “We’re thinking about drafting you.”

To himself, Hammond said, “Yes!,” thinking the scout liked his hitting.

The scout continued. “I think we’re going to draft you as a pitcher.”

“Pitcher?” Hammond asked.

Sure enough, the Reds selected him in the sixth round in 1986. As a pitcher. He signed for a $500 bonus.

In the minor leagues, some of the higher draft picks who received hefty bonuses motivated Hammond. When they brazenly announced the Reds would be calling them up soon, Hammond thought, “Not if I can help it.” He wanted to prove he was as good as they were. Pushing himself, his confidence soared during his third year of professional baseball. As a Double-A Chattanooga Lookout, he won 16 games, lost five and maintained a 1.72 ERA. “I knew I could pitch,” he says.

Despite the success, Hammond did not target the big leagues as a priority or even a goal. “Don’t have your goal to pitch in the major leagues because, if you have a goal like that, very few kids will reach that goal,” he says. “And, to me, that’s what hinders them from moving on. If you have a bad game, who cares? You’re getting paid to play baseball. If your goal is to make it to the major leagues, you hit three or four bad games in a row. You’re probably going to have three or four bad games in a row after that. Because you’re going to start getting down on yourself.”

Hammond progressed methodically through the Reds’ minor-league system. Thinking of his superb season in Double A, Hammond observes a difference in today’s game compared to when he played. “How many pitchers in today’s time would have an 18-5 [record] with a 1.60 [ERA] and not get called up from Double A? Nobody even mentioned that I should get called up. That’s baseball back then. You didn’t go to Triple A yet,” he laughs.

That he did in 1989, starting 24 games and going 11-7 for the Nashville Sounds (American Association) with a 3.38 ERA. He started the 1990 season with Nashville again and posted a spectacular 15-1 record with a 2.17 ERA. In midseason, he earned a brief callup to the big leagues, making his major-league debut on July 16, 1990, against the Montreal Expos. New to the big leagues, Hammond endured some rites of passage like carrying a veteran’s luggage. And wearing a fan’s pungent clothes.

“We were in Pittsburgh, and this guy, this old drunk, he runs down to the bullpen. You could smell him,” Hammond says. “And he throws his sports coat into the bullpen. It was a getaway day, and I had to wear it. But compared to everybody else and what they had to do, I was happy to wear that thing.”

During his first season in the big leagues, Hammond appeared in three games — all starts — and was 0-2 with a 6.35 ERA. He stuck with Cincinnati for the full season of 1991 (7-7, 4.61) and 1992 (7-10, 4.58). From 1990 to ‘92, Hammond started 47 games for the Reds, but his career shifted when the National League added two expansion teams in 1993, the Colorado Rockies and the Florida Marlins. Prior to the Marlins inaugural season, the Reds traded Hammond to the Fish on March 27.

“The first time you’re traded,” Hammond explains, “you feel let down. Like your team has given up on you.”

Hammond didn’t get bogged down in feeling rejected, though. “With the Marlins, we were just a bunch of young kids going out there and having a ball,” he says. “I lost my first three games, and if I was with anybody else, I’d probably be in the bullpen or down in the minor leagues. But they come up to me after the game, ‘Come on, man! We know you can pitch!’”

Pitching coach Marcel Lachemann delivered the same upbeat message. “He believed in me,” Hammond says. “He built my confidence. He would tell me, ‘You can pitch. Don’t let the results from this game effect your next game.’”

Lachemann believed in Hammond even after a dismal spring training in 1994 when hitters rocked him and his earned run average spiked to 12.00. Some coaches urged Lachemann to move Hammond to the bullpen.

Lachemann refused. “This is spring training,” Lachemann said. “You use spring training to get ready for the season. We can’t go by stats in spring training when you have a veteran pitcher.”

With the vote of confidence, Hammond responded by starting the season against the Los Angeles Dodgers and Ramon Martinez. Hammond’s line: 7 2/3 innings, four hits, no runs, and six strikeouts. “I got the win: one to nothing,” he says. “I owe a lot to Marcel Lachemann. He believed in what I could do.”

He also found an ally in his catcher, Charles Johnson. “He presented such a big target. He was great.”

Hammond appreciated Johnson’s acumen in pitch selection. “I wanted a catcher that could care less about if he’s a good hitter. Good hitters: they strike out, bad call, whatever. They bring it to the next inning, and I’m shaking off, shaking off. That’s why I enjoyed throwing to backup catchers. His goal is to call a good game.”

Between innings, Johnson sat next to Hammond and discussed strategy. Hammond liked this one-on-one communication, something he fears may be disappearing from today’s game.

Hammond also enjoyed spacious Joe Robbie Stadium as his home field. “I loved it. Big stadium. You can get away with throwing fastballs.”

These factors coalesced into success. In June 1993, he won all six of his starts and earned National League Pitcher of the Month honors. During the Marlins first season, he led the team in wins with 11. The next season, he pitched 25 2/3 consecutive scoreless innings. In ’95, he threw two shutouts en route to a 9-6 campaign with a 3.80 ERA.

But, injuries started to set Hammond back. He made only nine starts in 1996 and pitched primarily in relief (5-8, 6.56 ERA). After the season, the Marlins advised Hammond they wanted him to transition to a bullpen role. He wasn’t interested, especially after the Boston Red Sox offered to sign him as a starter. His contract with Boston was laden with starter incentives, bonuses based on innings pitched and wins. Despite the incentives and the intent, Hammond wound up in Boston’s bullpen, appearing in 29 games but making only eight starts (3-4, 5.92 ERA). The switch left Hammond disenchanted. He returned to the Marlins in ’98 and pitched in three games, going 0-2 with a 6.59 ERA in 13 2/3 innings. By that point, he liked the idea of spending more time with his young family at his ranch in Wedowee, Alabama better than he liked the idea of playing baseball. With his wife experiencing a difficult pregnancy, Hammond retired, happy to care for his family and perform the various tasks needed to maintain his spread, a deer and hunting reserve with a 20-acre bass lake.

Three years removed from the game, Hammond was 35 years-old. After his wife mentioned her regret that their kids hadn’t seen him pitch, Hammond started getting his arm in shape. He let teams know he was interested in pitching again. The Cleveland Indians reciprocated interest, signed him to a minor-league contract and assigned him to their Triple A team in Buffalo, New York.

Hammond pitched well with an ERA below 2.00. He threw so effectively that teammates and he wondered if the Indians would call him up to the big leagues. Then he heard a rumor that the Indians wouldn’t promote any pitcher who didn’t throw at least 90 miles per hour.

Hammond asked his agent about the rumor. Hammond said, “If it’s true, tell them I want my release.” Three days later, the Indians released Hammond. “I guess the rumor was true,” he laughs.

A few days passed, and the Atlanta Braves called. Their message: we don’t care how hard you throw so long as you get hitters out. After that, Hammond began pitching for their Triple-A team in Richmond, Virginia. And, during his 2001 season in Triple A, Hammond delivered with 10 wins, four losses, and a 2.95 ERA in 49 appearances.

Hammond says he wasn’t pitching any differently compared to his prior seasons in the big leagues. “I’ve always been able to throw the ball where I want to. Throw my off-speed where I want to. Command the strike zone.”

Hammond’s changeup was key to his success. He could vary the pitch’s speed, moving it from 72 miles per hour to 58. In fact, his mastery of the changeup caught the attention of Braves pitchers as they gathered in early 2002 at Turner Field for Camp Leo, a pre-spring training workout for pitchers.

“Everybody’s out there sitting around the bullpen, and one guy gets up, and he starts throwing. And, to me, that’s nervous,” Hammond says.

With all eyes on him, Hammond stepped onto the mound. “Throw some fastballs. Spin a couple of curveballs. And then I throw a changeup.”

Relief pitcher Mike Remlinger watched Hammond’s off-speed pitch and said, “What was that?”

“Changeup,” Hammond said.

Remlinger smiled. “Throw that again!”

Hammond obliged. Now, Braves pitchers like Greg Maddux, Tom Glavine, and John Smoltz took note and raved, “That is awesome!”

The changeup coupled with Hammond’s excellent control led Atlanta Braves manager Bobby Cox to call Hammond into the dugout near the end of spring training. “Hammy,” Cox said. “Looks like you’re going to make our club.”

Hammond smiled. “Bobby, I wasn’t going to Triple A. I can pitch.”

“Show me,” Cox said.

And, after being away from the big leagues for four years, Hammond took the mound at Atlanta’s Turner Field on April 4, 2002. In the top of the seventh inning with one out, he faced Dave Hollins of the Philadelphia Phillies. As Hammond toed the rubber, he wasn’t thinking about the long road back to the big leagues, the stops in Buffalo and Richmond, the odds against a 36-year-old returning to pitch at the highest level after a lengthy layoff. “All of that was overshadowed by the fact that my family’s watching,” he says.

Hammond struck Hollins out.

“I had a lot of focus,” Hammond says about both that game and his comeback season. “I pitched every game like it was my last.”

Hammond enjoyed many aspects of his time with the Braves, including its leadership, manager Bobby Cox and pitching coach Leo Mazzone. “I liked a manager that if me, Greg Maddux, Chipper Jones and John Smoltz all walked into his office together, we’re all on the same page. He doesn’t show any favoritism.”

Cox was thrown out of a record 158 games.3 Hammond says this demonstrates Cox’s support for his players. “He has your back. Whether you’re right or wrong, you’re right.”

Pitching coach Mazzone likewise looked out for players. Before each game, Mazzone made the rounds, checking in with each pitcher to see how he felt. “If you didn’t say right off the bat, ‘I’m good,’ Leo would be like, ‘Hammy?’ If I said I was a little tired, he’d go, ‘You’ll be the last pitcher we use. We’re going to get you a day off.’”

With the Braves, Hammond pitched middle relief. In hindsight, he wishes he had transitioned to that role earlier in his career. “If I had to do it over again, for a guy who threw in the mid- to upper 80s, and I had mastered the off-speed. I had a great changeup. Really good slider. And a good curveball. For somebody to come in in the sixth, seventh, or eighth inning and pitch one or two innings, hitters don’t want to face somebody who has mastered the changeup. They want the fastball. And I can get in and get out, and they don’t have time to adjust over two or three at-bats.”

As he settled in to the bullpen, Hammond enjoyed its camaraderie. “We had a ball. We’d watch the game and tell stories. Darren Holmes and I, we’d tell stories about hunting and fishing.”

In 2002, John Smoltz began his role as the Braves’ closer. Not only did he make an immediate impact by saving 55 games, but he also became an advocate for the relief pitchers. Seeing the bullpen room, Smoltz said, “This room is too small. We need to be able to relax in here.”

When the relievers returned from their next road trip, they walked into an expanded bullpen room, four times larger than it had been before. “They’ve got a big-screen TV in there and two lounge chairs. And then, every road trip we’d go on: another lounge chair,” Hammond says.

Hammond describes the rest of his pen mates as a “bunch of no-fit guys that all fit together,” discarded arms the Braves pieced together to form one of the league’s best relief staffs. Thirty-six-year-old left-hander Mike Remlinger made 73 appearances and posted an ERA below 2.00. Darren Holmes also received a considerable amount of work; he, too, carried an ERA below 2.00. Hammond believes one reason for the corps’ success was wanting to do well for Atlanta’s front-line starters. “For me, it all had to do with who got the start. When you’re coming into a ballgame for Greg Maddux, Tom Glavine, those guys—it puts a lot of pressure on you.”

The pressure worked for Hammond as, from the end of June 2002 through the remainder of the season, Hammond gave up no earned runs and had a 35 2/3 scoreless inning streak.

“For the last half of the season, I mowed them down.”

As his ERA dropped, he began pushing to end the year with it below 1.00. “It was a personal thing. Nobody talked about it. It was kind of like a no-hitter where you don’t say anything about it when you’re trying to get it.”

As the season wound down, Hammond’s goal of finishing with an ERA below 1.00 was within reach. But one game against the Florida Marlins made him wonder whether he came close only to be disappointed.

He started the seventh inning by issuing a walk. Kevin Millar then ripped a line-drive double to the right-center gap. Facing no outs and runners on third and second, he thought, “All this for nothing.” Then he reminded himself: focus. Focus on the hitter. Pitch to him like this is the last hitter you’ll ever face.

Mike Lowell hit a ground ball to the shortstop who made an easy throw to first base. One out.

Hammond intentionally walked Derrek Lee. Bases loaded.

On an 0-1 pitch, the next hitter popped out to second base. Two outs.

Hammond breathed deeply. “Focus!” He watched the signs from his catcher, Henry Blanco, and delivered the pitches. The Marlins’ Mike Redmond lined out to first base.

Out of the jam and knowing his sub-1.00 ERA was secure, Hammond displayed emotion for the first and last time that season. He pumped his fists, tossed his head back, and howled for joy. “I was excited. I felt fifteen feet tall.”

After his incredible 2002 season when he went 7-2 in 63 relief appearances, Hammond became a free agent.

“I told my agent I didn’t want to play in New York or on the west coast. I wanted to stay closer to home.”

While Hammond was hunting on his reserve, his agent, Bo McKinnis, called. “What are you doing?” McKinnis asked.

“Deer hunting,” Hammond whispered.

“Well, I’ll be quick. The New York Yankees called.”

“I told you,” Hammond said. “We ain’t playing in New York.”

“Well, they offered two years. This amount: $5.6 million.”

“Whoa!” Hammond screamed, shattering the silence surrounding the deer stand and sending any nearby bucks fleeing. “We’re playing in New York!”

Pitching for the Yankees offered some highlights, like pitching in Roger Clemens’s 300th win (“The fans booed me when I came in. They wanted Roger to keep pitching.”). But, it also presented some peculiarities.

“As soon as you walked into the clubhouse, you’d see 20 reporters,” Hammond says. “You can get there at 12 o’clock, right after lunch. There’s 20 reporters there, waiting for something to happen. And it keeps a team from being a team. Because I never saw [Roger] Clemens. I never saw Derek] Jeter. Bernie Williams and [Jason] Giambi. It was just me, a few of the relievers and a few of the bench guys. They didn’t want to ask us anything.”

Not that Hammond felt isolated. Andy Pettitte had kids around the same ages as Hammond‘s, so the two pitchers brought their children to the ballpark early to throw batting practice to them.

Yankees fans were very demanding. As he prepared for his first home series, he heard comments from teammates about The Gauntlet.

“What’s The Gauntlet?” Hammond asked.

“You’ll see.”

Pitcher Jeff Nelson finally explained to Hammond that a barricade separates players as they walk from the stadium to their cars. “Every game, there’s hundreds of fans there. And if you do good, they cheer you on. If you did bad—because they could care less what you did last night. It’s what you did tonight. If you did bad, they will let you know about it.”

One night, after following a player who had had a bad game through The Gauntlet, Hammond resolved not to have a bad game. “You can look up my stats at Yankee Stadium that year. I think I gave up one run that whole year. I told myself, ‘Me and my family ain’t walking through no Gauntlet.’” Indeed, Hammond pitched well as a Yankee in 2003, winning three games in 62 appearances and posting a 2.86 ERA.

Hammond spent three more seasons on a big-league mound — for the Oakland A’s (2004 — 4-1, 2.68), San Diego Padres (2005 — 5-1, 3.84), and, coming full circle in 2006 to where his career began, the Cincinnati Reds (1-1, 6.91).

Hammond knew it was time to retire when his kids quit wanting to join him at the ballpark. “They’d rather stay with their neighborhood friends and play kickball. And I remember driving home one night after my last game, and I just felt that was it. I ain’t going back. So I get home, and my wife has the TV on. Lights are out. And I went around on that bed. Sat down right next to her, and I go, ‘I just played my last game.’”

Lynne was relieved.

Hammond said, “I’m going to pray that the Cincinnati Reds somehow release me before I get to the field.” He said this because, if the Reds released him, he would get paid through the remainder of the season.

The next day, Hammond received a call from his agent.

The Reds released him. After a 14-year big-league career, Hammond retired with a 66-62 record, 4.14 ERA, three shutouts, three saves, and 1,123 2/3 innings pitched.

Post-baseball, Hammond started the Chris Hammond Youth Foundation. Its goal is to help bring organized sports to underprivileged children.

“When God put us in Wedowee, Alabama, and me growing up in Vestavia where we had everything, and once my kids started experiencing what kids in rural areas experience—not much—I’m like, this is a tragedy.” The foundation helps build ballparks, install lighting, provide equipment—whatever is needed for kids to play sports. “If you play on an organized team, no matter what it is, to me it helps build the characteristics and everything that helps prepare you for life. What having a job is all about.” The foundation raises money by accepting donations (“I’m happy when somebody gives us five dollars.”) and by hosting an annual auction paired with a golf tournament. Hammond wants tournament participants to have fun.

“I want there to be something on every hole, so folks are like, ‘Oh, look! Full Moon Barbecue’s coming up on the next hole! Can’t wait for some Full Moon!’ I want lots of giveaways for the players, and I want everybody to have a good time.”

Hammond doesn’t place goals on the foundation to raise X amount of money and build Y number of baseball fields annually. Instead, his approach is to reach people with his message. As more learn about the foundation, support will grow and the building will continue.

Hammond maintains his ties with the Atlanta Braves, and he enjoys participating in the team’s alumni activities. “It’s fun for my kids. We’ll go back to Atlanta and see Chipper Jones. He’ll be like, ‘What’s going on, Hambone?’ My kids get a kick out of that. I like it, too, getting that respect from your teammates.”

Work with the foundation keeps Hammond busy, but he has fun by “being the hands, feet and voice of Jesus Christ in a lost world.” A religious man, Hammond questions the strength of religion in the United States, with some churches transforming worship service into an hour of entertainment. And he notes that, with America’s resources, in which most have a roof over their heads and three meals a day, people lose sight of right from wrong and become more focused on material pursuits. The people who hit bottom—they are the ones most open to hearing God’s message.

Hammond meets these people by working in a prison ministry. “These guys, the ones who know they need to turn their lives around, they’re looking for the right path. Some of them haven’t made it yet, but the ones who are looking for a better way, I’m happy to help them.”4

Last revised: August 30, 2018

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Bill Nowlin and fact-checked by Chris Rainey.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 Mike Dodd, “Hammond Comes Back in Big Way for Braves,” USA Today, September 30, 2002.

2 All quotations from Chris Hammond are, unless otherwise attributed, from interviews done by the author on August 20, 2015, August 1, 2018, and August 17, 2018.

3 Matt Monagan “Happy Anniversary to Bobby Cox Breaking MLB’s All-Time Ejection Record,” August 14, 2015.,Cut 4 by MLB.com: https://www.mlb.com/cut4/happy-anniversary-to-bobby-coxs-record-setting-132nd-ejection/c-142984996

4 A prior version of this biography appeared as “Less Than One: Chris Hammond” in Doug Wedge, Baseball in Alabama: Tales of Hardball in the Heart of Dixie (Charleston, South Carolina: The History Press, 2018).

Full Name

Christopher Andrew Hammond

Born

January 21, 1966 at Atlanta, GA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.