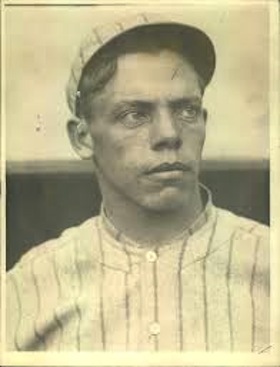

Ferdie Schupp

Seventy-three, 61, 60, .406, 104, 130, 1.12, and 383: these are some of the best known batting, baserunning, and pitching marks in single-season history. Another received almost similar respect in the years prior to World War II but has since been nearly forgotten. When Ferdie Schupp turned in a 0.90 ERA in 1916, a standard that remains the lowest recorded by a qualifying pitcher since the statistic became official, The Sporting News reported: “The New York Giants southpaw who didn’t get started until after mid-season, made a new and remarkable record for pitching effectiveness.”1 The record books and sportswriters recognized Schupp’s best-ever ERA broadly and widely for many years. In just one example out of many, the 1943 Sporting News Baseball Guide and Record Book listed Schupp under “Lowest Earned-Run Average, Season, Majors.” It was only post-WWII that his ERA title gradually faded from some of the record and reference sources.

Seventy-three, 61, 60, .406, 104, 130, 1.12, and 383: these are some of the best known batting, baserunning, and pitching marks in single-season history. Another received almost similar respect in the years prior to World War II but has since been nearly forgotten. When Ferdie Schupp turned in a 0.90 ERA in 1916, a standard that remains the lowest recorded by a qualifying pitcher since the statistic became official, The Sporting News reported: “The New York Giants southpaw who didn’t get started until after mid-season, made a new and remarkable record for pitching effectiveness.”1 The record books and sportswriters recognized Schupp’s best-ever ERA broadly and widely for many years. In just one example out of many, the 1943 Sporting News Baseball Guide and Record Book listed Schupp under “Lowest Earned-Run Average, Season, Majors.” It was only post-WWII that his ERA title gradually faded from some of the record and reference sources.

Ferdinand Maurice Schupp was born on January 16, 1891, in Louisville, Kentucky. Schupp’s grandfather on his father’s side, also Ferdinand, was born in Germany and immigrated to the United States. His father, Ferdinand F Schupp, was born in Louisville in 1867 and became a roofer. Schupp’s mother, Sophia (Erning) Schupp, was a year younger than her husband and born in Ohio. Younger brother Clarence and sister Pearl rounded out Schupp’s household in his youth.

Schupp went to duPont Manual High School in Louisville, and although he left school two months before graduating, in 2011 he was inducted into the school’s Hall of Fame. Nevertheless, there is some doubt that Schupp ever played baseball for the school. In 1920 he told writer John Ward: “I pitched ball as far back as I can remember, but I never represented any school team. … They had a good ball team in that school but I never tried to play on the team. I don’t know exactly why. I guess my objections to school were so strong that they overcame my natural fondness for baseball.”2 When Schupp dropped out he found a job in a dairy where he worked long hours, but it was “better than going to school.”3 After recovering from a bout of typhoid fever, Schupp quit the dairy and went to work with his father.

While helping his father in the roofing business, in 1911 Schupp played semipro baseball in the Louisville area. Local bird-dog scout John Ray recommended Schupp to the Reds, who sent him a contract and invited him to spring training the following year. Just before he was about to depart, however, the Reds changed their mind, and unconditionally released the young hurler, also costing Ray his $100 bonus. By this point several minor-league teams had heard of Schupp as well, and from among his options Schupp selected Decatur, Illinois, in the Class-B Three-I league.4

Schupp was still relatively slight of build and manager Chick Fraser initially used him in relief. In his first appearance Schupp mistakenly took the mound wearing his old Louisville semipro uniform, and the game had to be delayed while he changed. Schupp quickly overcame this embarrassment, and over the remainder of the season he had little rest in Decatur, hurling 365 innings and finishing 22-20 in 51 games, nearly 40 percent of the team’s 136. He also reportedly set the league’s single-season record for strikeouts (265) and walks (148).5

New York Giants scout Dick Kinsella, one of baseball’s most prominent ivory hunters, recognized Schupp’s talent and snapped him up for Giants manager John McGraw. Kinsella succeeded in purchasing the future star despite the fact that Chick Fraser was the brother-in-law of Pittsburgh manager Fred Clarke and was supposedly keeping an eye out for major-league-caliber talent.6 At Decatur Schupp had reportedly “solved the problem which has been studied by pitchers for 50 years – how to throw a rising curve … a curve that changes from a straight ball to a perceptible arc upward. … Schupp has so mastered the ball, it is alleged that he can put a terrific amount of smoke behind it and still keep the rising curve.”7

Despite his renowned pitch, the lanky, youthful-looking pitcher had difficulty breaking into a Giants staff that had just won two consecutive pennants. Coach Wilbert Robinson nevertheless saw something in Schupp and persuaded McGraw to keep him.8 Schupp was a free-spirit who often tried McGraw’s autocratic nature, but he also had an enchanting smile and always wormed his way back into his manager’s good graces: “He is said to be about the only player McGraw ever had who could ‘kid’ the manager and he was so popular with his teammates that McGraw would have faced a rebellion almost had he fired the boy as he threatened to so often.”9

“Schupp was a carefree kid who never grew up,” wrote Harry Grayson. “Life to him was one sweet song. He never felt that club rules should be applied to him. He was a dark complexioned chap with high cheekbones, gray eyes, brown hair inclined to be curly and a smile that revealed a fine set of teeth.”10 Among baseball writers the phrase “Can he row?” with the response of “I should say he can,” became a well-known expression after a challenge between sportswriter Frank O’Neill and Giants road secretary Eddie Brannick. “On the Giants’ Pullmans,” wrote Fred Lieb, “Pitcher Ferdie Schupp would ask the question, and the entire team would chime in, ‘Well, I should say he can.’”11 Schupp also had an exceptional tenor voice and organized the team’s barbershop quartet, occasionally expanding to a sextet or double quartet depending upon the singing talent of his teammates.12 Schupp could also play the piano and “with a package of cigarettes handy … would pound one forever – blue music and the jumping jive stuff so popular today.”13

Schupp finally debuted on August 19, 1913, pitching a total of only five games during the season. Over the next two years he saw little action – 31 games and 73? innings pitched –mainly due to his wildness. He walked 38 men and news articles routinely referred to his lack of control. During this time Schupp became close friends with Rube Schauer, another young Giants hurler whom McGraw also used sparingly. The duo, known as the “Schush Twins,” often frustrated McGraw, who hoped they would settle down and develop into star hurlers. In fact, McGraw would often use Schauer in relief of Schupp, leading famed New York sportswriter Heywood Broun to write, “First it Schupps, and then it Schauers.”14

Several observers felt McGraw’s initial usage of Schupp and Schauer slowed their development: “The matter of handling a man can make or mar his future. Connie Mack’s system of ‘playing his recruits on the bench made wonders of Stuffy McInnis, Eddie Collins, Jack Barry, Amos Strunk and others. The same tactics used with Schauer and Schupp by McGraw apparently robbed those youngsters of their original confidence. The handling of boys fresh from the ‘sticks’ is a task worthy of masters of psychology.”15

On June 9, 1914, Schupp married Minnie Schaefer, also from Louisville. Available records indicate the couple had one son, also Ferdinand, but the marriage only lasted several years. Schupp later married Eleanor Brown from Missouri, and available records again suggest the couple had a son, Spencer, who died in the Philippines in 1944.16

The 1916 season turned out to be a roller-coaster campaign for the Giants and a breakthrough for Schupp. The team lost 13 of its first 15 games, but then won 17 in a row, without Schupp yet seeing any action. Eventually, on June 13, Schupp relieved Sailor Stroud, pitching two scoreless innings. Schupp performed well in relief over the next several weeks, finally earning his first start of the season on July 13. He surrendered 11 hits in his complete game, but only one earned run. In his next start, one week later, Schupp gave up only four hits and one earned run, but was largely relegated to the bullpen thereafter.

Finally, on September 7 with the Giants floundering at 59-62, McGraw inserted Schupp into his pitching rotation. Schupp surrendered only two hits and one run, and the win kicked off the greatest winning streak in major-league baseball, 26 straight wins (with one tie). Schupp deserves much of the credit for New York’s streak, turning in one of the greatest pitching stretches in baseball history. He started, completed, and won six games, giving up 3 runs (2 earned), 17 hits, and 10 walks while striking out 24 batters in 54 innings pitched. Research by Sean Forman confirmed that this was one of only four such streaks in baseball history (six consecutive games totaling at least 125 opponent at-bats, 1914 to present) to hold opponents below a batting average of .100.17 Tom Ruane looked at the data slightly differently, showing Schupp is one of only 10 pitchers since 1914 to hold opposing hitters below .100 over 150 consecutive opponent at-bats (including relief appearances). For the season as a whole, he gave up 79 hits, a .167 opponent batting average. Schupp designated the September 28 game as the one he remembered best: “Buck Herzog, who was playing second base, was beefing over something with the Braves’ first base coach. So when Big Ed Konetchy, their first baseman, hit a dribbler Herzog didn’t even make a move for it, and I lost my no-hitter.”18

Schupp finished the season with an ERA of 0.90 and was universally credited with National League’s ERA title. He pitched in 30 games, surrendering 14 earned runs in 140 innings and qualifying for the ERA title under that season’s criteria as detailed more specifically in The National Pastime. Current record books mostly recognize Grover Alexander as the ERA leader for his 1.55 mark, but this required a rewriting of the verdict at the time and for many years thereafter. In 1940, for example, Robert Milne wrote in Baseball Magazine, “And that pitching performance [Schupp in 1916] created a baseball hurling record that has not been equaled to this day.”19 More detail on Schupp’s case can be found in the 1996 Baseball Research Journal on page 3.

After the season one sportswriter described his pitching: “Schupp has nice speed, and gets it with apparently little effort. He has a good slow ball and delivers it with the same motion as his fast one. He has a stylish looking curve with a sharp break that behaves like a loving child and he makes a runner stick to first base like a porous plaster; he does this by employing a peculiar half-kick motion, as he delivers the ball, that looks as though he intended to throw to first.”20 Schupp self-described his pitching repertoire: “I depend upon speed and curves with a change of pace. The first curve I ever threw in my life broke four feet. But you can’t throw curves all your time, if you do they will be laying for you, so I mix them up and manage to get by.”21

As to his new-found success, Schupp didn’t have any particular explanation, but clearly believed he should have been used more regularly earlier in his career: “No, there wasn’t any unusual cure for my wildness last year. It was merely steady practice, pitching continually at one spot, that did it. I think I might have come through faster, though, if I had been used to a start a few regular games sooner than I did.”22

Not surprisingly, after his great second half in 1916, Schupp opened the 1917 season in the rotation. He turned in another great season, finishing 21-7, leading the league in winning percentage, finishing fourth in ERA at 1.95, and helping lead the Giants to the pennant. In the World Series against the Chicago White Sox, Schupp struggled in his first start in Game Two, lasting only 1? innings, although he was not charged with the loss. He came back in Game Four to throw a seven-hit shutout, but the Giants eventually lost the Series in six games. Former major-league pitcher and future longtime Columbia baseball coach Andy Coakley was effusive in his praise: “That fellow is some pitcher. I don’t see how any one bats against him effectively. He has the best curved ball I ever looked at, and I’ve looked at a few in my time. The most remarkable thing about it is his control. He sweeps it over the outside edge high or low, or on the inside, with as great ease as Matty used to do. I never saw a southpaw pitch that way. The more stuff they have the wilder they usually are.”23

After his two stellar seasons, McGraw had high expectations for the 27 year-old heading into the 1918 season. “But that winter I went to a camp,” Schupp recalled. “There was snow on the ground, I think maybe I caught cold in the arm, though it didn’t bother me then, but the next spring I was up against it. The very first ball I tried to pitch in spring training, a sharp pain struck through my shoulder and my arm went dead. I couldn’t do anything with it.”24 Conversely, there were later rumors that the easy-going left-hander had injured his arm in a fight that offseason.25 Still another report had him hurting his arm while pitching during spring training at the Giants training camp in Marlin, Texas.26

In any event, Schupp was not ready for the start of the season, and as his arm showed few signs of coming around, the club sent him to Bonesetter Reese, an injury specialist in Youngstown, Ohio, who famously worked with athletes. After stating that he popped a tendon close to the shoulder back into place, Reese told Schupp he would be ready to go after resting his arm for least a week.27 Unfortunately, Schupp’s struggles returned once McGraw sent him back out to the mound: in his first appearance of the season, one inning in relief on June 6, Schupp yielded three runs; a month later when Schupp finally received his first start, he gave up ten runs in eight innings, walking 10 men. McGraw then used Schupp sporadically throughout the remainder of the war-shortened season, including one more start.

After the season, Schupp, like all American men of military age in a “non-essential” occupation was required to either join the military or take a job in an “essential” industry. Schupp went to work with a shipbuilding company in New York with other Giants, including Larry Doyle and Art Fletcher, and played on the company’s baseball team.28 When the war ended the government canceled the “work or fight” decree, and the ballplayers were free to return to baseball.

Schupp visited a Louisville specialist over the winter, and both he and McGraw hoped his treatment plus a winter of rest would allow Schupp’s arm to return to its pre-injury form. One newspaper reported that his offseason therapy also consisted of a strict diet, and that he reported to the Giants much leaner. And during spring training there was some reason for optimism. After one game in late March the New York Times reported that in his pitching motion, “he pulled his left shoulder completely around, something he could not do last year.” McGraw told the paper, “I have great hopes that he will be able to come around. He is much looser in his motion than he was last Spring. We will have plenty of work for him.”29

The optimism of the spring dissipated quickly once the season started, however, and on July 16, with Schupp 1-3 with an ERA of 5.63, McGraw swapped him to Branch Rickey and the St. Louis Cardinals for catcher Frank Snyder. Schupp claimed his arm was fine, and that with regular work he would regain his ability and command.30 To help him along, the innovative Rickey, in his first year managing the Cardinals, devised a contraption of “strings on poles to indicate the strike zone” to facilitate Schupp’s relearning the strike zone.31 Schupp made his first start for St. Louis on August 8, and pitched fairly regularly over the remainder of the season. He didn’t rebound to his previous form, but he brought his ERA down to 4.34 by season’s end and finished the year on a high note, tossing a 12-inning complete game while surrendering only six hits and one run.

The modest rebound continued in 1920, as Schupp went 16-13 with a 3.52 ERA and finished third in strikeouts per nine innings. Yet he couldn’t reconquer his wildness as he had earlier in his career and led the league in walks. When the lack of control carried over into early 1921, Brooklyn manager Wilbert Robinson targeted Schupp as a potentially bargain-priced rehab project. Robinson remembered Schupp from his days as a Giants coach and had been trying to acquire the lefty for the past couple of years (on the cheap if possible). Robinson believed that Schupp’s problem was more mental than physical, and that as he had with Rube Marquard, he could rebuild the pitcher’s confidence and cure his wildness.32 To land Schupp (and reserve infielder Hal Janvrin) Robinson dealt Jeff Pfeffer to the Cardinals.

Robinson, though, had no more success with Schupp than his previous managers. Despite a one-run, complete-game victory in his first appearance for Brooklyn, Schupp ended up in the bullpen and finished with an ERA of 4.57 for the Dodgers. Now 30 years old, Schupp had pitched over 100 innings only once (1920) since his stellar 1917 season. When Schupp failed to impress at spring training in 1922, Robinson gave up on his project, selling him to Kansas City in the American Association, one step below the majors.

After Schupp started 5-1 for Kansas City, Chicago White Sox owner Charles Comiskey acquired him for three players and cash, a total package reportedly worth $50,000, but in fact the overall value must have been significantly less. At the time teams often exaggerated the value of the players sent to the minor-league team in the exchange to enhance the status of their new addition.33 In Chicago Schupp’s command reached new lows, and he walked 66 batsmen in 74 innings. Comiskey cut his losses in early August, selling Schupp to Seattle in the Pacific Coast League, another league one notch down. Schupp was reportedly “dissatisfied” in Seattle, and over the winter Seattle sold him back to Kansas City for $4,500.34

In 1923 Schupp began a seven-year stretch in the American Association during which he tossed at least 198 innings every season. His best year was his first of three in Kansas City, when he finished 19-10, and in the Little World Series against Baltimore, Schupp won three games, including the decisive Game Nine, while losing only once. During the offseason Schupp lived in Southern California and played in the California Winter League.

After the 1925 season St. Paul acquired the lefty for infielder Luke “Danny” Boone. But with the Saints Schupp’s uninhibited personality came to the fore, and he was suspended for not following team rules – quickly reduced to only one day once the team realized it was short of pitchers. In August owner Bob Connery finally let him go permanently, selling Schupp for the $3,500 waiver price to Indianapolis, where Schupp pitched capably for three years.35

Schupp started the 1930 season in Fort Worth in the Texas League but the club gave up on him after an 0-5 start. Schupp caught on with Minneapolis for a brief time but the club released the now 39-year-old hurler in late July after seven games and a 6.63 ERA. Shortly after his release Schupp signed with a semipro team to start a well-publicized game in central Minnesota against a team that boasted Negro League star John Donaldson as its hurler.

After his Organized Baseball career ended, Schupp moved to permanently to Southern California, working for the Shell Oil Company in Long Beach. He also spent time with the Lincoln Supply Company, headquartered in Victorville. Schupp died in 1971 at the age of 80; he is buried in Calvary Cemetery in Los Angeles.

Nearly forgotten today, at his prime in 1916-17 Schupp was one of baseball’s best pitchers. “I don’t want to seem extravagant in my praise,” Andy Coakley said in 1917, “But if there has ever been Schupp’s equal in recent years he has escaped my notice. I wouldn’t give him for any other pitcher in baseball today if he were my property.”36 Years later, St. Louis Star sports editor James Gould wrote regarding his record-setting 1916 season: “Never before had such an earned-run average been compiled and, by the beard of all baseball prophets, never since!”37 By the beard of all baseball prophets, one day Schupp will once again receive his due for the 1916 NL ERA title.

Notes

1 “Ferd Schupp Makes Remarkable Record for Effectiveness in Box,” The Sporting News, November 30, 1916.

2 John J. Ward, “A Big League Pitcher Who Came Back,” Baseball Magazine, August 1920, 428.

3 John J. Ward, “A Big League Pitcher Who Came Back,” Baseball Magazine, August 1920, 428.

4 John J. Ward, “A Big League Pitcher Who Came Back,” Baseball Magazine, August 1920, 428; The Sporting News, November, 26, 1916.

5 “Ferd Schupp of the Giants,” The Sporting News, November, 26, 1916.

6 “Ferd Schupp of the Giants,” The Sporting News, November, 26, 1916.

7 “His Rising Curve,” Sporting Life, December 28, 1912.

8 “Schupp a Winner at Last,” Pittsburgh Press, September 27, 1916.

9 “Ferd Schupp of the Giants,” The Sporting News, November, 26, 1916.

10 Harry Grayson, “Schupp Didn’t Last Long but Pitching Mark Still Stands,” St. Petersburg Evening Independent, July 15, 1943.

11 Frederick Lieb, “A Barrel of Fun in the Press Box,” The Sporting News, May 2, 1962.

12 James M. Gould, “Will They Ever Equal This One: Baseball Records are Made to be Broken, But the Mark of Ferdy Schupp Seems Destined to Stand Forever,” Baseball Magazine, July 1938, 375.

13 Harry Grayson, “Schupp Didn’t’ Last Long but Pitching Mark Still Stands,” St. Petersburg Evening Independent, July 15, 1943.

14 The Sporting News, July, 2, 1942.

15 C.J. Koefed, “The Youngsters of 1916,” Baseball Magazine, July 1916.

16 Much of the information on Schupp’s family life comes from the records available at Ancestry.com.

17 Sean Forman, email correspondence, April 7, 2014.

18 Harold Peterson, “Mugsy McGraw and His Giants on a Seesaw,” Sports Illustrated, July 17, 1967.

19 Robert C. Milne, “Halting the Hitters,” Baseball Magazine, May 1940, 551.

20 J.J. Ward, “The Most Effective Pitcher,” Baseball Magazine, July, 1917.

21 John J. Ward, “A Big League Pitcher Who Came Back,” Baseball Magazine, August 1920, 459.

22 J.J. Ward, “The Most Effective Pitcher,” Baseball Magazine, July, 1917.

23 “Coakley Praises Schupp,” Pittsburgh Press, June 14, 1917.

24 John J. Ward, “A Big League Pitcher Who Came Back,” Baseball Magazine, August 1920, 428.

25 “Old Ferdie Staging a Comeback,” Milwaukee Journal, June 15, 1927.

26 “Loss of Schupp Is Big Setback to Giants Club,” Minneapolis Tribune, July 7, 1918.

27 “Schupp’s Arm Is Treated,” New York Times, May 14, 1918.

28 “Schupp on His Way to Springs for Arm,” El Paso Herald, December 5, 1918.

29 New York Tribune, April 9, 1919; “M’Graw’s Pitchers Get Good Workout,” New York Times, March 26, 1919.

30 “Cards Give Snyder for Ferdie Schupp,” New York Times, July 17, 1919.

31 Lee Allen, “Cooperstown Corner,” The Sporting News, May 24, 1969.

32 “Ebbets Crowed Too Soon It Seems,” The Sporting News, March 11, 1920; “Dodgers Count Hal Janvrin Real Asset,” The Sporting News, June 23, 1921.

33 The Sporting News, May 25, 1922; “White Sox Release Schupp,” New York Times, August 6, 1922.

34 “Pongs Purchase Miller, Gardener, From Lansing,” Minneapolis Tribune, December 19, 1922.

35 “Indians Get Ferdie Schupp From St. Paul,” Milwaukee Sentinel, August 28, 1926.

36 “Coakley Praises Schupp,” Pittsburgh Press, June 14, 1917.

37 James M. Gould, “Will They Ever Equal This One: Baseball Records Are Made to be Broken, But the Mark of Ferdy Schupp Seems Destined to Stand Forever,” Baseball Magazine, July 1938.

Full Name

Ferdinand Maurice Schupp

Born

January 16, 1891 at Louisville, KY (USA)

Died

December 16, 1971 at Los Angeles, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.