Dave Davenport

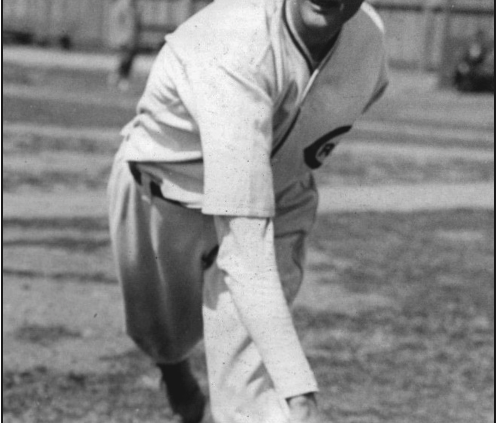

Among the tallest players of the Deadball Era, Dave Davenport was a 6-foot-6 behemoth and rugged right-handed workhorse. Two months after debuting with the Cincinnati Reds in 1914, Davenport jumped his contract and joined the St. Louis Terriers of the Federal League. The following season he laid claim as that circuit’s best pitcher, winning 22 games and leading the league in innings, starts, complete games, shutouts, and strikeouts, and coming within one-tenth of a percentage point of leading the club to the pennant. Davenport also had a reputation as a carouser and his lifestyle eventually led to his suspension from Organized Baseball after parts of six seasons.

Among the tallest players of the Deadball Era, Dave Davenport was a 6-foot-6 behemoth and rugged right-handed workhorse. Two months after debuting with the Cincinnati Reds in 1914, Davenport jumped his contract and joined the St. Louis Terriers of the Federal League. The following season he laid claim as that circuit’s best pitcher, winning 22 games and leading the league in innings, starts, complete games, shutouts, and strikeouts, and coming within one-tenth of a percentage point of leading the club to the pennant. Davenport also had a reputation as a carouser and his lifestyle eventually led to his suspension from Organized Baseball after parts of six seasons.

David Warren Davenport was born on February 20, 1890, in the small town of DeRidder, the parish seat of Beauregard, located in southwestern Louisiana, on the Texas border.1 His parents were Thomas Louis and Sarah (Hamilton) Davenport, who married around 1878 and welcomed 13 children into the world, nine of whom survived childbirth; Dave was the third oldest surviving child.2 (Brother Claude, born in 1898, forged an 11-year career in professional baseball, and appeared in one game with the New York Giants in 1920.) The Davenports were farmers and relocated around 1895 to DeWitt County, Texas, about 90 miles east of San Antonio, and farmed, especially cotton. Dave completed one year of high school and then dropped out to work the land and tend to his family’s crops.

A life toiling in the Texas heat must not have seemed too enticing for Davenport, who by the age of 19 was already full grown and weighed about 200 pounds. He claimed he took “French leave,” abandoning the abode without informing his folks, in 1909, to earn some money on large cotton plantations, and soon thereafter “ran into a ball club.”3 Nine months later he returned to his parents, who by that time were living on a farm near Runge, in nearby Karnes County. Davenport pitched for a local semipro club in Runge and in 1911 for the Victoria Rosebuds in the Class-D Southwest Texas League.4 After that team disbanded in August (and the league at the end of the season), Davenport signed with the San Antonio Bronchos of the Class-B Texas League in 1912, pitching in the latter part of the season.5 Back with Bronchos in 1913, the 23-year-old Davenport emerged as one of the circuit’s hardest throwers in his first full season of Organized Baseball. He posted a 15-16 slate for a sub-.500 ballclub (74-78), logged 270 innings and tied for the league lead in strikeouts with 204. In mid-August he was sold to the Cincinnati Reds for a reported $4,000.6

Davenport reported to skipper Buck Herzog at the Reds’ spring-training camp in Alexandria, in central Louisiana in 1914. Coming off a dismal seventh-place finish (64-89) and their worst winning percentage since 1901, the Reds were looking to shore up their pitching corps and were willing to take a chance on the elongated recruit twirler from the low minors, though little was expected from him. Davenport surprisingly landed a spot on the staff, and made his big-league debut on April 17 at Redland Field in the Queen City, hurling four innings of relief, yielding two hits and an unearned run to the Chicago Cubs. Eight days later, Davenport made his first start, also against the Cubs, at West Side Grounds, the dilapidated wooden ballpark that was located in what is now the University of Illinois-Chicago campus, on the near west side of the city. Davenport “hurled the sphere down from his great height at puzzling speeds and defiant angles,” gushed sportswriter Jack Ryder in the Cincinnati Enquirer, and “had the Cubs gasping for breath.”7 On May 30 Davenport blanked the Pittsburgh Pirates on six hits at Forbes Field. His future looked bright, but discontent was brewing on the squad. The Federal League, a third major league, with teams in eight cities, began operation in 1914; a bidding war with the NL and AL for players ensued, driving up salaries. On June 3 Armando Marsans, a speedy, Cuban-born up-and-coming-star who had received MVP votes in 1912 and 1913, informed club owner August Herrmann in a legally obtuse letter that he was giving his 10-day notice to leave the team; according to the Enquirer, Davenport submitted an exactly-worded letter to Herrmann, as well.8 Ryder reported that Marsans had been in contact with the St. Louis Terriers and had “persuaded” Davenport, “a green youngster, who did not know any better,” to join him in his strike.9 The club summarily suspended Marsans, but not Davenport. However, Davenport, supposed enticed by a $1,000 bonus and a two-year contract for $4,500 (much more than his $225-a-month salary with the Reds), jumped his contract, joining the Terriers 10 days after submitting his letter to Herrmann.10

The Terriers, piloted by pitcher Mordecai “Three-Finger” Brown, were an awful club, headed to the worst record (62-89) in the Federal League. Davenport was bombed in his first five appearances, posting a 7.07 ERA in 28 innings and losing two decisions. On July 12 he posted his first victory for the Terriers, tossing a four-hitter against the Kansas City Packers, at Handlan’s Park, one of three big-league parks in St. Louis, located at the intersection of Grand and Laclede Avenues, on what is now the campus of Saint Louis University. (The Browns played about 1.7 miles north at Sportsman’s Park; and the Cardinals a mile northwest of that ballpark at Robison Field.) Two games after Davenport blanked the Buffalo Buffeds on two hits in the Gateway City, Fielder Jones, who had led the Chicago White Sox to the World Series title in 1906, replaced Brown. Under Jones, Davenport’s workload exploded. Over the final six weeks of the season, he made 15 appearances, completing 9 of 12 starts, though he won just 5 of 13 decisions. For the season, he logged 269⅔ innings and fanned 164 (including a Federal League-most 5.9 batters per nine innings), despite a 10-15 slate.

The Terriers conducted spring training in Havana in 1915. Skipper Jones “demands discipline,” promising to whip the team into shape after Brown’s lenient ways, wrote the St. Louis Star and Times. 11 The strength of the club was pitching, which was a far cry from the previous season when the staff owned the worst team ERA (3.59) in the Federal League. It featured Davenport; former New York Giants star Doc Crandall, a pioneering reliever and starter; and 284-game winner Steady Eddie Plank, formerly of the Philadelphia Athletics. The Terriers, however, got off to a slow start and were just .500 at the end of May before winning 12 straight games (June 12-23), the final nine on the road. Three of those victories were by Davenport, who won six consecutive starts in just 17 days, including two shutouts. “Fielder Jones is one of that rare species of boss who believes in working a pitcher as often as possible when he is going well,” opined the Star and Times.12 And Davenport proved to be Jones’s workhorse. On two days’ rest, Davenport started both games of a doubleheader on July 31 against the Buffeds in St. Louis. In the first he tossed a four-hit shutout; in the second game “he tossed even greater ball than he did in the opener,” gushed the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.13 He yielded just one hit, an eighth-inning double, leading to the only run of the game and was saddled with a tough-luck complete-game loss. The Terriers engaged the Pittsburgh Rebels and the Chicago Whales in an exciting pennant chase in September. Davenport began the month red-hot, tossing a career-best and Federal-League season-long 30 consecutive scoreless innings.14 Included were a five-hit and a two-hit shutout sandwiched around a sparkling no-hitter against Chicago in St. Louis on September 7. Davenport had the “Whales completely mystified,” opined sportswriter Sam Weller in the Chicago Tribune, “with his curves and deceptive fast one.”15 In a five-day stretch (September 22-26), Davenport tossed three straight complete-game victories, the first of which was his 20th win of the season, and the last pushing the Terriers into a tie for first place. The pennant came down to the last series of the season with the Packers. Davenport started two of those games, and was collared with tough-luck losses in each as the Terriers scored just one total run. The Terriers won the most games in the league, yet finished in second place (87-67), .001 behind the Whales (86-66).

The Terriers boasted three of the Federal League’s nine 20-game winners, including Crandall (21-15) and Plank (21-11). In an extraordinary season, Davenport (22-18) led the league in games pitched (55), starts (46), shutouts (10), innings (392⅔), strikeouts (229), and fewest hits per nine innings (6.90); and tied for fourth in ERA (2.20). His “first class pitching was directly responsible for the great showing of the Terriers,” argued Sporting Life.16 He tossed a no-hitter, lost a one-hitter, and fired two two-hitters and four three-hitters, leading the Star and Times to boast that he was “one of the greatest hurlers” in all of baseball.17

Given the moniker Long Dave by sportswriters, Davenport was the tallest player in the league.18 Weighing about 220 pounds, with brown hair and eyes, the suntanned Davenport evoked an imposing impression on the mound. “[He] has an arm like a steel rod and a hand that simply smothers the ball,” wrote the Star and Times, “and a physique that would enable him to pitch every other day in the season if necessary.”19 During spring training with the Terriers in Havana in 1915, Davenport’s size brought him unexpected notoriety from the local populace. Another 6-foot-6 dark-haired giant, heavyweight boxer Jess Willard was training there in preparation for his much-anticipated title fight with champion Jack Johnson on April 5. According to one report, locals constantly referred to Davenport as “Americano Willard.”20

Davenport relied primarily on two pitches, his heater and a curveball. “Only Walter Johnson has more speed,” opined sportswriter W.R. Hoefer in Baseball Magazine in 1917. “[W]hen the hop on his fast one is zipping just right, Davenport is almost unhittable.21 In the same publication William A. Phelon called Davenport “as classy a speed merchant [as] any manager could wish to gaze upon.”22

After two litigious seasons with the National and American Leagues, the Federal League folded after the 1915 season. According to the “Peace Agreement” signed with the NL and AL, the Federal League withdrew the antitrust law suit it had filed (and which Federal Judge and future Baseball Commissioner Kenesaw Landis permitted to languish in hopes that the two sides would negotiate a settlement). All contract jumpers were immediately reinstated and the players from six of the eight teams were sold to the highest bidder. Owners of two Federal League clubs were permitted to purchase financially strapped teams: Phil Ball, majority owner of the Terriers, acquired the Browns from Robert Lee Hedges, while Whales owner Charles Weeghman purchased the Cubs; both Ball and Weeghman combined the rosters of their two teams.23

Overnight, the moribund Browns franchise was infused with star pitching, including Davenport, Plank, and Bob Groom, who had logged almost 500 innings for the Terriers in two seasons. Fielder Jones replaced Branch Rickey in the dugout. Rickey was relegated to the role of business manager, but soon clashed with Ball and left the club.

The Browns were a perennial doormat who hadn’t had a winning season since 1908, but a pervasive mood of optimism wafted through spring training in Palestine, Texas. Jones whipped 17 Browns and 12 former Terriers players into shape for a 22-player roster. Sportswriter W.J. O’Connor gushed that it was the “most impressive looking lot of men, athletically speaking, that ever have represented a St. Louis ball club.”24 Davenport began the season by tossing a complete-game six-hitter to beat the Cleveland Indians, 4-2, at League Park on April 13. Over the next 2½ months, he notched only one more victory; the Star and Times labeled him a “hurling failure.”25 Firmly ensconced in seventh place (37-49), the Browns made an unlikely run back into contention, winning 14 straight games beginning on July 23, and 23 of 25 through August 12 to move to within 4½ games of the lead. A major reason for the club’s success, Davenport re-emerged as a dependable workman. Three days after hurling a six-hit complete game to beat the Philadelphia Athletics, 5-1 on July 26, Davenport pulled another ironman stunt — both on one day and in a series. “Dave Davenport’s Arm and Bat Win Two From Yanks” read the headline in the Post-Dispatch, as the “long leviathan, started and completed both games of a twin bill against the AL leaders in the oppressive St. Louis heat.26 He twirled a four-hitter to win the opener, 3-1, then a seven-hitter to complete the sweep, 3-2, in the second contest, in which he also rapped a two-run double. (Never a threat at the plate, Davenport batted .104 lifetime on 49 hits). Two days later Davenport relieved Earl Hamilton with the bases loaded in the ninth and extinguished the fire to preserve a 4-2 win over the Yankees. Then he made his third start in the six-game series against the visitors, throwing four-hit ball over eight strong innings in an eventual 3-2 Browns victory in 14 innings. Davenport won all six of his decisions in August, extending his winning streak to nine games. He made just three starts in September and lost his only decision as the Browns collapsed, wining just nine of 26 games in the month and eventually finishing in fifth place, but with a winning record (79-75). Davenport (12-11) led the majors with 59 appearances (of which 31 were starts) and ranked fifth in the AL in innings (290⅔).

Davenport’s dismal performance in September seemed to result from his excesses away from the diamond and the resulting clashes with Jones. The Post-Dispatch described Davenport as “temperamental” and local sportswriters made frequent references to his “condition” and “shape,” which were euphemisms for drinking.27 After the season there were reports that Jones was fed up with Davenport and had actively shopped him as trade bait. “Jones doesn’t fancy this chippie’s conduct off the field,” opined Browns beat writer W.J. O’Connor. “For the world now knows that Dauntless Dave behaves to suit himself.”28

Aside from whether Davenport drew Jones’s ire for breaking training rules, nobody doubted the big Texan’s toughness, which was never more evident than at the beginning of the 1917 season. In mid-February Davenport apparently accidentally shot himself at his home in Runge, Texas, after a hunting trip. According to the Post-Dispatch, a bullet from a high-powered rifle “entered under [Davenport’s] lower ribs on his left side and ranged upward, coming out below his collar bone. It then passed his jaw and gazed his eyebrow, but didn’t injure the eye.”29 Hospitalized in nearby Cuero, Davenport shrugged off the injury and announced that he would be ready when the season started. Despite missing all of spring training and apparently pitching only batting practice to get into shape,30 Davenport suited up on Opening Day, and started the Browns’ sixth game of the season, pitching four-hit ball over five innings and yielding two runs in a no-decision against the Indians in St. Louis. Davenport slowly worked himself into shape, but struggled, and his record was just 4-9 with a 4.25 ERA in July 9. He then hit his stride, emerging as the club’s best pitcher, and one of the AL’s most effective, for the remainder of the season.31 On July 16 Davenport “had his old rifle fire curve working in great shape,” quipped St. Louis sportswriter John E. Wray, paying homage to the pitcher’s injury, blanking the Athletics on two hits at Sportsman’s Park.32 In his next outing, he held he held the Senators hitless for eight frames, settling for a three-hitter.33 Beginning with his four-hit shutout of the Athletics at Shibe Park in the City of Brotherly Love on August 9, the Big Texan spun five consecutive route-going triumphs in just 14 days for an offensively challenged squad that scored the fewest runs in the AL. Davenport proved to be one of the few bright spots on a miserable seventh-place (57-97) club, notching 13 of the team’s 26 victories (all by complete game) from July 13 to September 26. Despite his gruesome preseason wound, Davenport remarkably led the AL in starts (39), completing 20 of them, and led the staff with 17 wins (he also lost 17) and 280⅔ innings (3.08 ERA).

At the Brownies’ 1918 spring-training camp in Shreveport, Louisiana, Davenport was touted as the staff’s ace. Once the season started, however, “Long Dave” struggled, losing six of his first seven decisions; through late June his ERA hovered well above 5.00. It was a different story over the last nine weeks of the season, when Davenport once again transformed into one of the league’s most effective hurlers, posting a 2.05 ERA from June 28 through September 2, when the season officially ended about a month early because of World War I. Davenport won only 10 games all season, but five of those came in a 15-day stretch on the road in August, twice winning his second game of a series pitching on one day of rest, and yielding just five earned runs in 47 innings (0.96 ERA). He commenced his most overpowering stretch on August 14 with an 11-inning victory over the Athletics, the fourth and last time he hurled at least 10 innings in a big-league game. After blanking the eventual World Series champion Red Sox, 1-0, on six hits at Fenway Park on August 22, Davenport “made the Yankees look and feel very small,” gushed the Post-Dispatch, holding them to four hits in another whitewashing, 2-0.”34

With World War I waging in Europe, Davenport had applied for a military draft exemption, citing his family. Around 1916 he had married Lillian Calloway, and together they had their first child, Howard (three more would follow, two daughters and another son).

One month into the 1918 season, Secretary of War Newton D. Baker enforced Provost Marshal General Enoch Crowder’s “work or fight” decree, and required that all men working in non-essential jobs must either apply to work in war-related industries or risk being drafted.35 Industrial leagues all over the country began recruiting players from Organized Baseball. Davenport accepted a job at Bethlehem Steel Corporation’s massive Alameda Works Shipyard, near Oakland, California. He joined skipper Clarence Brooks’ plant team, which consisted of several big-leaguers including his Brownie teammates Joe Gedeon and Ernie Johnson, the White Sox’ Swede Risberg, as well as Ossie Vitt and Bob Jones of the Detroit Tigers.36

Davenport didn’t have far to travel to the Browns spring training site in San Antonio in 1919. A “superior brand of pitching,” cooed sportswriter Clarence P. Lloyd optimistically, “is expected to make a first division club out of the Browns this season.”37 Supposedly in the best shape of his life after playing ball in the Bay Area for much of the offseason, Davenport was described as “working harder than at any other time” and “taking life a bit more seriously” (another euphemism for less drinking).38 In the annual preseason exhibition series with the St. Louis Cardinals in the Gateway City, Davenport tossed two complete-game victories, yielding only one earned run, and subsequently was chosen to start the season opener for the first time in his career. He was shelled for six hits and three runs by the White Sox at Sportsman’s Park, and the season soon careened out of control, as the Big Texan squabbled with skipper Jimmy Burke, who had taken over the club in mid-1918. Their conflict escalated on June 10 after Davenport yielded four late runs in a loss to the Athletics in Philadelphia that dropped his record to 1-6. Infuriated, Burke immediately sent the pitcher back to St. Louis for the final two weeks of the Eastern swing.39 Davenport rejoined the team, started sporadically and relieved, but didn’t fare any better, his record falling to 2-11. After pitching an inning of scoreless relief in the first game of a doubleheader against the Indians on September 1, Davenport did not show up at Sportsman’s Park the following day. According to reports from the Post-Dispatch and Star and Times, he arrived at the park during the late innings of the series finale with the Indians on September 3. Burke ordered his pitcher to wait in the clubhouse until after the game, at which time he informed him in writing that he had been suspended for the remainder of the season and fined $100.40 A heated verbal exchange developed and Davenport apparently threatened to hit his skipper, when business manager Bob Quinn entered the scene. The big Texan confronted Quinn, who ultimately called the police to have his player forcibly removed from the grounds. “[Davenport] had been drinking, it was plain to me,” Quinn told the press, and vowed that he was through with the team.41

Davenport’s ugly scene with Burke and Quinn not only marked the end of his big-league career, but also his playing days in Organized Baseball. His days of pitching were far from over, however. The Browns immediately attempted to unload their disgruntled hurler to the highest bidder, but found none interested until the Washington Senators took a chance shortly before spring training was set to commence in 1920.42 Unable come to terms with the pitcher, club owner Clark Griffith returned him to the Browns in March.43

In parts of six big-league seasons, Davenport posted a 73-83 slate and a 2.93 ERA in 1,537 innings, appeared in 259 games, and completed 96 of 186 starts, including 18 shutouts.

Still formally the property of the Browns, Davenport refused to report and was suspended by the National Commission, the governing body of Organized Baseball. For the next decade he was a pitcher for hire, “outlawing” in a number of independent leagues not part of the National Agreement, and in semipro leagues across the country.44 In 1920 he starred for Rexburg (Idaho) in the Snake River Yellowstone League.45 The following season, he set the outlaw Northern Utah League on fire, winning all seven of his starts, including a perfect game, and averaging 16 punchouts a game for the Ogden Gunners.46 In a remarkable yet odd decision, the league, pressured by owners of the other teams, decided to “fire” Davenport because he was too good for the circuit.47 A wildly popular player because of both his size and ability, Davenport subsequently played on teams in Colorado, Iowa, Nebraska, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, and Wyoming as the decade progressed. By the end of 1921, Davenport expressed a desire to return to Organized Baseball. In May 1927 Commissioner Kenesaw Landis formally reinstated Davenport, then 36 years old.48 There were reports that the he would sign with the Milwaukee Brewers of the American Association, one notch below the majors, but skipper Jack Lelivelt apparently had second thoughts because of his reputation.49

By 1930 Davenport lived with his wife, Lillian, and their four children in Aransas Pass, in San Patricio County, about 30 miles west of Corpus Christi, in southeastern Texas. He was employed as a shipping clerk50 and later worked on various WPA projects.51 On October 16, 1954, Davenport died at the age of 64 in El Dorado, Arkansas, where he was employed as a cab driver. The cause of death was prostate cancer.52 He was buried at Arlington cemetery in El Dorado, and was survived by his wife and four children.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also accessed Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com, SABR.org, The Sporting News archive via Paper of Record, the player’s Hall of Fame file, and the online archives via Newspaper.com, and Ancestry.com.

Notes

1 The place of birth is from Davenport’s official Certificate of Death. Some sources give his place of birth as Alexandria, Louisiana, located in the geographic center of the state.

2 According to multiple US Census reports.

3 Dent McSkimming, “Dave Davenport Is an Expert at Cotton Picking,” St. Louis Star and Times, March 29, 1915: 29.

4 “What Former Rosebuds Are Doing,” Weekly Advocate (Victoria, Texas), September 7, 1912: 3.

5 “Three Runge Boys with Bronchos,” Houston Post, March 16, 1913: 19.

6 Associated Press, “Texas Man Goes Up,” Topeka (Kansas) State Journal, August 16, 1913: 8.

7 Jack Ryder, “Long Dave,” Cincinnati Enquirer, April 26, 1914: 18.

8 Jack Ryder, “Marsans,” Cincinnati Enquirer, June 4, 1914: 6.

9 Ibid.

10 “Necrology,” The Sporting News, October 27, 1954: 24.

11 “Terrier Pilot and 8 Players Florida Bound,” St. Louis Star and Times, February 23, 1915: 11.

12 Fred Bendell, “Crandall Comes Back and Trims Newark, 3 to 2,” St. Louis Star and Times, June 17, 1915: 10.

13 “Davenport Twirls Double Bill; Loses One Hitter,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 1, 1915: 1S.

14 The Federal League record for scoreless innings was 33 by Buffalo’s Russ Ford in 1914.

15 Sam Weller, “No-Hits, No Runs Off Davenport,” Chicago Tribune, September 8, 1915: 11.

16 Willis E. Johnson, “The Terriers’ Toppers,” Sporting Life, December 11, 1915: 12.

17 “One of the Greatest Hurlers in Game Is Feds Pitcher,” St. Louis Star and Times, December 17, 1915: 13.

18 Hans Rasmussen, who logged two innings for the Chicago Whales was also 6-feet-6.

19 “One of the Greatest Hurlers in Game Is Feds Pitcher.”

20 “Robbers Relieve Terrier Player of Watch; Tobin May Play in Cuba,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 13, 1915: 8.

21 W.R. Hoefer, Baseball Magazine, February 1917, quoted in Bill James and Rob Neyer, The Neyer/James Guide to Pitchers (New York: Fireside, 2004), 179.

22 William A. Phelon, Baseball Magazine, January 1917, quoted in Bill James and Rob Neyer, The Neyer/James Guide to Pitchers (New York: Fireside, 2004), 179.

23 For more on the end of the Federal League see Brendan Macgranachan, “Federal League, Part Three, Seamheads.com, March 28, 2008. seamheads.com/blog/2008/03/28/the-federal-league-part-three/; and Gary Hailey, “Anatomy of a Murder: The Federal League and the Courts,” The National Pastime 4 (1985): 62-73.

24 W.J. O’Connor, “Dave Davenport Is in Line; Only Four Absentees,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 1, 1916: 9.

25 “Too Much Faith in Groom Costs Jones Another,” St. Louis Star and Times, May 27, 1916: 6.

26 W.J. O’Connor, “Dave Davenport’s Arm and Bat Win Two From Yanks,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 30, 1916: 27.

27 W.J. O’Connor, “Jones’ Men Lose When Ump Misses Strike on Ness,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 18, 1916: 16.

28 W.J. O’Connor, “Deal for Shotton Is Now Unlikely,” Record Too Good,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, December 8, 1916: 20.

29 “Dave Davenport Not Dangerously Injured,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, February 15, 1917: 19.

30 “Dave Davenport Expects to Pitch Within Two Weeks,” St. Louis Star and Times, April 10, 1917: 13.

31 From July 13 to September 26, Davenport went 13-7, completed 15 of 22 starts, and posted a sparkling 2.21 ERA in 163 innings while with the Browns.

32 John E. Wray, “Sloan’s Queer Play to Be Probed with a Nut Pick,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 17, 1917: 17.

33 Clarence F. Lloyd, “Foster Breaks Up 0-Hit Game for Long Dave,” St. Louis Star and Times, July 21, 1917: 10.

34 “Browns Meet Yankees in Double Bill Today; Davenport Is Winner,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 27, 1918: 16.

35 Matt Kelly, “On Account of War,” National Baseball Hall of Fame. baseballhall.org/discover-more/stories/short-stops/1918-world-war-i-baseball.

36 “Winter Baseball Has Hurt Professionals,” Oakland Tribune, November 30, 1918: 8.

37 Clarence P. Lloyd, “Pitching Expected to Elevate Browns to First Division,” St. Louis Star and Times, January 25, 1919: 8.

38 “Josh Billings to Be Browns’ ‘First String’ Receiver,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 21, 1919: 26.

39 “Burke Says Davenport Is ‘Through” as Result of Row in Club House,” St. Louis Star and Times, September 4, 1919: 14.

40 “Police and Baseball Bat Quell Dave Davenport in Row at Browns’ Clubhouse,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, September 4, 1919: 4.

41 Ibid.

42 James M. Gould, “Heydler and Johnson May Name Woodruff for Commission Job,” St. Louis Star and Times, February 12, 1920: 20.

43 “Dave Davenport Turned Back to Brownies, Says Dispatch from Tampa,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 10, 1920: 126.

44 “Dave Davenport Wants to Rejoin American League,” St. Louis Star and Times, December 15, 1921: 21.

45 “Dave Davenport Has Remarkable Season,” Calgary (Alberta) Herald, October 1, 1920: 30.

46 “Davenport Hurls No Hit No Run Contest for Gunners,” Ogden (Utah) Standard-Examiner, July 3, 1921: 10.

47 “Urban Faber Continues Form,” Waco (Texas) News-Tribune, July 18, 1921: 5. See also, “Keep Dave Is Cry of Fans,” and “B.B. Officers Defer Action,” both in Ogden (Utah) Standard-Examiner, July 8, 1921: 7.

48 “Landis Reinstates Davenport, Is Report,” St. Louis Star and Times, May 21, 1927: 12.

49 “Dave Davenport Not to Report to Brewer Club,” Journal-Times (Racine, Wisconsin), June 15, 1927: 19.

50 1930 US Census. Ancestry.com.

51 World War II Draft Registration Card. Ancestry.com.

52 Certificate of Death. Ancestry.com.

Full Name

David W. Davenport

Born

February 20, 1890 at Alexandria, LA (USA)

Died

October 16, 1954 at El Dorado, AR (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.