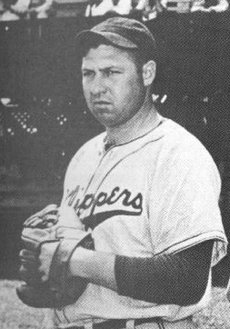

Hugh Casey

On Monday evening, September 22, 1947, the “sizzling steaks [were] on the house . . . [and] free gravy down the shirt front” was de rigueur at 600 Flatbush Avenue.1 Pitcher Hugh Casey, proprietor of Hugh Casey’s Steak and Chop House, was optimistically throwing a victory dinner party for his Dodgers teammates. Brooklyn’s beloved “Bums” stood poised to clinch their second National League pennant of the decade, and the right-handed relief ace, “a genial, happy host,” was delighted to treat.2

On Monday evening, September 22, 1947, the “sizzling steaks [were] on the house . . . [and] free gravy down the shirt front” was de rigueur at 600 Flatbush Avenue.1 Pitcher Hugh Casey, proprietor of Hugh Casey’s Steak and Chop House, was optimistically throwing a victory dinner party for his Dodgers teammates. Brooklyn’s beloved “Bums” stood poised to clinch their second National League pennant of the decade, and the right-handed relief ace, “a genial, happy host,” was delighted to treat.2

Some apprehension remained. Brooklyn had lost three consecutive games, allowing three chances to nail down the National League championship slip through their fingers. The Dodgers were idle this Monday. The St. Louis Cardinals, their closest competitors, were playing a doubleheader at home against the Chicago Cubs. At Casey’s joint, a group of Dodgers players and their wives huddled in a booth and anxiously awaited results of the nightcap from St. Louis.

Finally, close to midnight, the tavern’s manager happily announced the final score from St. Louis: Cubs 6, Cardinals 3. All hell broke loose, not only at Casey’s, but on the streets of Flatbush as well. An impromptu party broke out on Flatbush Avenue. Led by an unnamed accordion player, Dodgers players and their wives formed a conga line that joyously marched down Brooklyn’s major thoroughfare. The inn’s proprietor, Hugh Casey, quietly beamed and joined in the merriment.

Hugh Thomas Casey was born in Atlanta, Georgia, on October 14, 1913. He was the youngest of seven children (five boys, two girls) born to James Oliver Casey, a Fulton County police captain, and Elizabeth Casey. Young Hugh had already gained some notoriety as a hard-throwing teenage pitcher when he first encountered Wilbert Robinson, the legendary former Brooklyn manager. The two met in the early 1930s at Dover Hall, a former plantation just outside Brunswick, Georgia, that served as a hunting and drinking retreat for vacationing Northerners like Robinson. Robby immediately took a liking to the big Georgian—more at first for his hunting prowess than his ability on a baseball diamond—and hired Hugh as a sort of aide de camp.

Casey’s baseball talents soon became obvious to the ex-catcher when he noticed the oversized teen tossing rocks at empty whiskey bottles precariously balanced on fences. Robinson noted the pitcher’s superior velocity and pinpoint control; he threw hard and never seemed to miss hitting a bottle. Knowing a big-league prospect when he saw one, Robby took Hugh under his wing, encouraging and coaching him.

The Detroit Tigers signed Casey after he graduated from high school in 1931. In May 1932, after a brief stay in the Detroit system, in which he never appeared in a game, the Tigers dropped him. By 1934 Casey was pitching with his local team, the Southern Association’s Atlanta Crackers. It was his second go-around with the Crackers; he had unsuccessfully debuted with them as an eighteen-year-old two seasons earlier. In 1933 Casey logged a 19-9 mark for the Charlotte Hornets of the Class B Piedmont League, and he returned to his hometown with renewed confidence.

In 1934 the Crackers’ new president was Casey’s old mentor, Wilbert Robinson. Cincinnati Reds general manager Larry MacPhail was in Atlanta on a scouting trip and Robinson suggested to MacPhail that he sign Casey. MacPhail passed on Casey, but shortly thereafter the Chicago Cubs drafted him.

Casey spent the entire 1935 season with Chicago, but saw little action. “Sometimes I think [manager] Charlie Grimm never knew I was with the club. . . . I knew every blade of grass in every bullpen throughout the league,” Casey recalled.3 In his major-league debut, on April 29, he pitched two and two-thirds scoreless innings in a wild 12–11 victory over Pittsburgh at Wrigley Field. The official scorer ruled Casey the winning pitcher, but National League president Ford Frick later overruled that decision. The hard-throwing right-hander ended his rookie campaign having thrown only twenty-five and two-thirds innings in thirteen games, with an 0-0 record and a 3.86 earned run average. He was not included on the Cubs’ World Series roster, though he received a full share of World Series money.

Grimm sent Casey to Los Angeles of the Pacific Coast League the following March. Hugh hurt his arm while with the Angels and lost a great deal of velocity on his fastball. Forced to adapt, he quickly developed what he called a “splitter” to complement his excellent curveball; skeptics later claimed that Casey’s new pitch could be more accurately described by simply eliminating the “l.”

Toiling as a starter, Casey spent the next three seasons in the minors perfecting his craft and reinventing himself on the mound. In 1937, with Birmingham, he led the Southern Association with a 2.56 ERA. Ignoring concerns about Casey’s weight—he was six feet one but weighed well over 200 pounds— Brooklyn drafted him off the Memphis Chicks roster following the 1938 season.4

“He knows how to pitch,” determined new Dodgers skipper Leo Durocher after observing Casey in spring training in 1939.5 In his first starting assignment, on May 30, Casey drew as his opponent New York Giants’ ace Carl Hubbell. Before a crowd of nearly 59,000 at the Polo Grounds, Casey outpitched the future Hall of Famer, 3–1.

He finished the 1939 campaign 15-10 for a third-place Dodgers team, working mostly as a starter. At the time, Casey’s pitching repertoire consisted of a “sneaky fast” hard one, a pitch quicker than it appeared when juxtaposed with his superior curve, and his “splitter.” “He has a head on him—and he has heart,” said Durocher. “You won’t see him flinch in the jam.”6

On July 19, 1940, at Wrigley Field, with the Cubs enjoying a big lead, Casey entered the game in the eighth inning and plunked Cubs pitcher Claude Passeau between the shoulder blades. The enraged Passeau immediately hurled his bat toward the pitcher’s mound. Casey started toward the plate, but Brooklyn’s Joe Gallagher got there first and began pummeling Passeau. A full-scale brawl ensued, with the police required to intervene. This was far from the last time that Casey, who more than once admitted, “I’m a mean man on the mound,” would hurl a pitch in anger.7

Less than a year later, on May 19, 1941, Passeau got his revenge by connecting on a Casey fastball for a second-inning grand slam. Casey, who was the starting pitcher that afternoon, later claimed that the incident marked the start of his career as a reliever. After Passeau’s home run, manager Durocher stormed out to the mound to make a pitching change, screaming at his shell-shocked hurler, “You’re in the bullpen for the rest of your life.”8

Casey remained in the rotation until mid-July, but Durocher finally made the switch, and Casey finally found his true niche. In nineteen relief appearances between July 29 and the conclusion of the ’41 campaign, Casey posted a 2.23 ERA as the Dodgers stormed to their first pennant since 1920. Averaging two-plus innings-pitched per outing, the moon-faced reliever took the hill in six of the Dodgers’ ten contests between August 16 and 23. He finished the final ten games in which he appeared that September. “We couldn’t have won without Hugh Casey’s great relief pitching,” said Durocher at the end of the season.9

Brooklyn clinched the National League flag on September 25 at Braves Field in Boston. The Dodgers were to face the mighty New York Yankees in the two teams’ inaugural Fall Classic meeting. Casey strutted around Yankee Stadium before Game One and announced that he was more than ready for “them damn Yankees.” (Casey was never shy about his Southern roots.) “Ah promise to protect that advantage with mah life’s blood,” he exclaimed. “Which is the blood of the old South and the Confederacy, suh!”10 In the Series opener he made good on his boast, relieving in the sixth inning with two on base and retiring Phil Rizzuto and Red Ruffing on fly balls before he was lifted for a pinch hitter in the top of the seventh.

After the Dodgers won Game Two to tie the Series, the scene shifted to Ebbets Field and Casey’s fortunes turned for the worse. Durocher called on him in the eighth inning of a scoreless Game Three after starter Fred Fitzsimmons had been struck on the left knee by a drive off the bat of his mound opponent, Marius Russo. Hugh allowed a pair of Yankees tallies on four consecutive singles, including one by Tommy Henrich in which Casey was slow in covering first base. The final score was 2–1 Yankees.

Game Four was played on October 5, an unseasonably warm Sunday in Brooklyn. Called on to relieve Johnny Allen with two out in the fifth, Brooklyn trailing, 3–2, and the bases loaded, Casey got Joe Gordon on a fly to left to end the threat. The Dodgers took a 4–3 lead in the bottom of the inning on Pete Reiser’s two-run homer. Hugh doggedly guarded that slim edge until there were two out in the ninth.

Then, with Henrich again at the plate, Casey’s 3-2 curve—or was it a spitter?—broke sharply down and away from the mitt of Brooklyn catcher Mickey Owen and toward the backstop. Henrich, equally fooled by the pitch, flailed futilely at it, quickly glanced back, and then hustled to first. He arrived there safely before the frustrated Owen could recover. The Yankees then reached Casey for a single, two doubles, and two walks before he finally got the third out.

The Dodgers failed to score in the bottom of the ninth, and Casey was a loser for the second consecutive day. New York’s 7–4 victory gave them a commanding three-games-to-one lead. When they clinched the title the following afternoon, it seemed almost anti-climactic to Brooklyn fans.

Owen, who was charged with an error on the play, was practically in tears after the Game Four loss. “Sure, it was my fault,” he moaned. His batterymate was more philosophical about it, at least to the press. “I guess I’ve lost ’em just about every way now.”11 For the rest of his life, Casey maintained that the pitch was a curve and not a spitter.

After an offseason that included harrowing memories of the pitch that got away, questions about his military status, a threat by the pitcher to retire from baseball and instead pump gas in Atlanta (a weak ploy for more money), a separation from his wife Kathleen (Thomas) Casey, whom he had married in 1937, and an intense dieting regimen, it was Ernest Hemingway, and not fate, that nearly knocked Casey out.

With the Dodgers training in Havana, Cuba, in 1942, the author—who spent a lot of time there and was a big baseball fan—invited a group of Dodgers to accompany him for an evening of eating, drinking, and merriment. After several rounds of drinks, Hemingway sized up Casey and challenged him to a few rounds of boxing. Casey demurred at first, but after Hemingway sucker-punched him, Casey donned a pair of gloves and began to batter his host.

Tables, chairs, trays, and glasses went flying as the two inebriated men exchanged blows. At one point, Hemingway’s wife, journalist Martha Gellhorn, awakened by the commotion, came down from her bedroom to see what the ruckus was all about. Ernest assured her it was nothing serious. Finally, tired of being knocked down so often, the author administered a shot to Casey’s groin, and then surrendered.

Both Casey and the Dodgers began the 1942 campaign on fire. Going into a July 18 doubleheader at St. Louis, Brooklyn led the second-place Cardinals by eight games. Casey was sporting a tidy 1.80 ERA after seventy-five innings pitched, spread over twenty-nine appearances. In addition, he was doing his share for the war effort by visiting shipyard workers around the borough and lending a hand to the War Bond drive. Big Hugh was photographed often at one of those shipyards, the ever-present cigar wedged firmly in his mouth.

In the July 18 opener, Casey was nursing a 4–3 lead with two out in the sixth inning when a Stan Musial line drive fractured the pinky finger of his pitching hand.12 Casey tried to make the play, but threw wildly to first allowing both base runners to score in what eventually became a 7–4 Brooklyn defeat. Once removed from the contest, Casey sat in front of his locker and downed an entire pint of whiskey.13 Hugh’s broken finger kept him out of action until August 6.

The Cardinals, nine games behind the Dodgers as play started on August 11, won thirty of their next thirty-six games and vaulted into first place on September 13. Despite Brooklyn’s 10-2 streak to end the season, the Cardinals went 11-1, and the Dodgers fell two games short of repeating as National League champions. Casey contributed a 1.64 ERA in six games during that twelve-game span. The disappointment lingered with Hugh for years as military duty prevented him from seeing big-league action again until 1946.

Casey reported for active duty with the US Navy in January 1943 and spent the next three years in the military, rising to the rank of chief petty officer. Most of his time in the service, however, was spent playing ball. Released from active duty in December 1945, Casey reported to the Dodgers training camp in Daytona Beach, Florida, in the spring of 1946. Despite a rocky start and finish, he enjoyed another stellar season in the Dodgers bullpen, with an 11-5 record and a 1.99 earned run average.

On the final day of the season, the Dodgers and the Cardinals were tied for first place. With Brooklyn trailing the Boston Braves, 1–0, at Ebbets Field, Casey was called in to hold Boston in the ninth inning. But he allowed a walk and two hits before Durocher removed him. The Dodgers eventually lost, 4–0, but St. Louis lost also, necessitating a tiebreaking playoff for the first time in major-league history. With Brooklyn quickly dropping two straight to the Cardinals—holding a lead only in the first inning of Game Two—the relief ace’s talents were not required.

The Dodgers and Casey bounced back to win the pennant in 1947. Once again the Yankees provided the competition in the World Series and once again Brooklyn came up short. En route to the pennant, some cracks were beginning to appear in the façade of thirty-three-year-old Hugh Casey.

Despite eighteen saves in 1947—a figure that would have led the National League had saves been an official statistic—Casey had to shut down for the regular season in mid-September because of a lame shoulder and a kink in his right elbow. He had become mostly a spectator, albeit an enthusiastic one, when he threw his pennant-clinching bash at his bistro.

Casey’s ERA ballooned to 3.99, double what it was in 1946. This was also the first season he served entirely as a reliever, not starting a single game.14 Late on a May evening in the Park Slope section of Brooklyn, on the way to his Flatbush tavern, Casey struck and killed a blind man while driving his automobile. There were no criminal charges pressed against him, nor was he arrested. Questions remained, however, as to the state of his sobriety at the time of the accident.

In many ways the 1947 World Series was a showcase for the teams’ ace relievers: Casey and New York’s Joe Page. Casey established a World Series record by appearing in six games, five consecutively.15 He was credited with two wins and a save, allowing only one run and five hits in ten and a third innings. Page, whose numbers were not as good as Casey’s, received the greater accolades primarily for his five relief innings of no-run, one-hit pitching in the decisive Game Seven, won by the Yankees, 5–2.

If there was a moment of redemption for Casey in the ’47 Series, it came on a single pitch in the ninth inning of Game Four. With the bases loaded and one out, he induced his old nemesis, Tommy Henrich, to bounce into a 1-2-3 double play. Cookie Lavagetto’s pinch-hit, two-run, game-winning double in the bottom of the ninth denied New York’s Bill Bevens both a victory and the first World Series no-hitter. To Casey, Brooklyn’s dramatic 3–2 win made up for every game the Dodgers ever lost to the Yankees

By 1948 everything was beginning to go wrong for Hugh Casey. He reported to the Dodgers’ spring-training camp in the Dominican Republic grossly overweight, and later was sidelined by what was described as “a mysterious ailment.”16 On Opening Day, at the Polo Grounds, Casey was barely able to hang on to a 7–3 Brooklyn lead, allowing three runs to score before finally getting the final out with the tying run third base.

On May 20, during a loss to St. Louis, Casey beaned Cardinals catcher Del Rice. “The ball wasn’t more than an inch or so inside,” Casey muttered in his defense. But Cardinals manager Eddie Dyer “half-drawled” to Hugh: “You’re a better pitcher than that.”17

Then, four days later, Casey slipped and fell down a flight of stairs coming from his apartment, directly above his bar. Suffering “torn tendons and ligaments” after landing heavily on his right side, he did not pitch for more than two months.

Casey’s heavy drinking was becoming more and more obvious. Red Barber, the Dodgers’ broadcaster, noted that according to other Dodgers, Hugh’s bedtime routine included cigars, comic books, and a bottle of whiskey. He would lie in bed smoking the stogie, reading the comic books, and drinking his liquor straight until either “the bottle or he was finished.”18

After his injury, Casey made three successful “rehab” appearances for the semipro Bushwicks in early July before making his first appearance with the Dodgers. Pitching before a crowd of 65,000 at Cleveland’s Municipal Stadium on July 14, he tossed four and two-thirds effective innings in an exhibition game against the Indians. After pitching only thirty-six innings and posting an ERA of 8.00 in 1948, the Dodgers released him on September 29.

In October Casey, now thirty-five, signed with the Pittsburgh Pirates. Used sparingly, he appeared in only thirty-three games, often in a mop-up role. In two consecutive games against Brooklyn—June 25 and 26—Casey was battered by his ex-teammates. In the June 26 game, he twice threw pitches close to Jackie Robinson. His second delivery hit Jackie in the right knee. Robinson made several comments to the pitcher as he made his way to first base, but Casey just stared at him without saying a word. After the Pirates released him on August 10, Casey signed with the Yankees. He appeared in only four games and was ineffective in three of them.

Casey returned to his hometown Atlanta Crackers for the 1950 campaign, where he was reunited with former Dodgers teammates Dixie Walker, now the Southern Association club’s manager, and Whitlow Wyatt, their pitching coach. He won ten games working as both a starter and reliever for the pennant-winning Crackers.

But in 1950 Casey’s personal problems were beginning to mount. He was sued by a Brooklyn woman, Hilda Weissman, who alleged that Casey was the father of her son, Michael Hammond, born the previous November 2. “I know the girl,” Casey explained. “She used to hang around the ball park and the ball players in Brooklyn, and come into my bar and grill once in a while. But that’s all.”19

Weissman, however, described four evenings spent with Casey at Brooklyn’s St. George Hotel in January and February 1949. After a trial in December 1950, Casey was ruled the father of the child and ordered to pay $20-a-week child support to Weissman. He said he would appeal the verdict, while his wife Kathleen, who was by his side through the entire trial, was supportive. “My belief in my husband still stands,” she proclaimed after the verdict. “I know he is not guilty of being the father of this child.”

Meanwhile, Casey’s life continued to unravel. On January 31, 1951, a tax lien for $6,759.36 was filed against him for unpaid income taxes. Now sole proprietor of Hugh Casey’s Steaks and Chops, he feared he would lose the bar. Casey desperately tried hooking on with the Dodgers again for the ’51 season, but could get no further than pitching batting practice at Ebbets Field. He pitched once more at Dexter Park, in April 1951, this time as a member of the Hartford Indians against the Bushwicks. In May, Casey and his wife separated again, though Kathleen claimed it had nothing to do with the paternity suit.

A month later, in June 1951, Casey returned to Atlanta, ostensibly to try to settle his tax problems. He checked into the downtown Atlantan Hotel and allegedly told the bellboy that he was suffering from a leaking heart valve and had only ten days to live.

During the early morning of July 3, 1951, Casey made two phone calls from his hotel room. One was to his good friend Gordon McNabb, an Atlanta real-estate agent. The other was to his wife. In both cases, he announced that he was going to kill himself. With the estranged Mrs. Casey on the line begging him not to do it, Casey placed a 16-gauge shotgun to his head. At about the same time, McNabb and his wife were about thirty feet away from Casey’s room, rushing to stop him from acting out his threat. All three heard the single shot fired from the shotgun. According to Kathleen Casey, Hugh’s final words were, “I am innocent of those [paternity] charges.”20

When the news reached Casey’s bar, a group of patrons raised their glasses one final time to the man whose round face and ample body looked down on them in a portrait. A toast was proposed to “the guy who was kind to everyone but himself.”21 With Dixie Walker and Whit Wyatt serving as pallbearers, Hugh Casey was buried in the Mount Paran Church of God cemetery in Atlanta, Georgia on July 4, 1951.

Notes

1. Brooklyn Eagle, September 20, 1947.

2. New York Post, September 23, 1947.

3. Sporting News, March 28, 1940.

4. Los Angeles Times, October 7, 1938.

5. Baseball Magazine, February 1940.

6. Sporting News, March 28, 1940.

7. Baseball Digest, April 1948.

8. Ibid.

9. New York Times, September 27, 1941.

10. Los Angeles Times, April 21, 1936.

11. Los Angeles Times, October 6, 1941.

12. Ibid.

13. Red Barber, The Rhubarb Patch: The Story of the Modern Brooklyn Dodgers, p. 59.

14. Casey started two games in 1942 and one in 1946.

15. Reportedly, he realized his arm was sound enough to pitch in the Series only after throwing a baseball at teammate Vic Lombardi. The little left-handed pitcher had accused Casey of babying his arm by spending all his time in the clubhouse’s diathermy machine.

16. Chicago Tribune, March 26, 1948.

17. Brooklyn Eagle, May 21, 1948.

18. Red Barber, The Rhubarb Patch: The Story of the Modern Brooklyn Dodgers, p. 59.

19. New York Mirror, April 22, 1950.

20. New York World-Telegram and Sun, July 3, 1951.

21. Sporting News, July 11, 1951.

Full Name

Hugh Thomas Casey

Born

October 14, 1913 at Atlanta, GA (USA)

Died

July 3, 1951 at Atlanta, GA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.