Bo Jackson

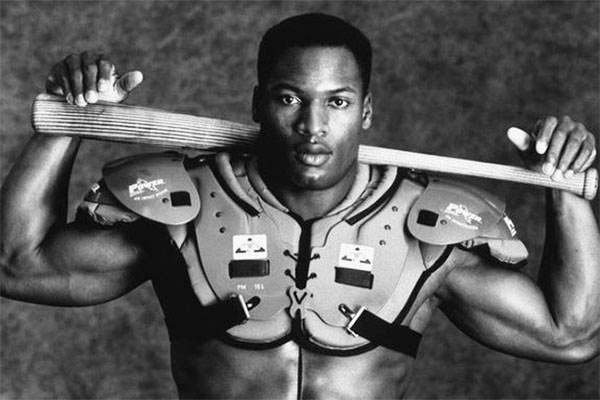

They were ubiquitous. They were funny. And for a while during the late 1980s and early 1990s, the Nike commercials that showed Bo Jackson playing everything from baseball to cricket to hockey — wearing the uniform of the storied Montreal Canadiens no less — brought the phrase “Bo Knows” into popular culture.

These commercials played on Jackson’s astounding athletic abilities. His abundant speed, power, agility, and quickness allowed him to play in the NFL and baseball’s major leagues. Although he wasn’t the first athlete to play two sports professionally — Jim Thorpe holds that distinction — he was the first to become an All-Star in the two leagues in which he played and the first to rise to prominence in the media-driven sports world of the late twentieth century.1

Bo Jackson was born on November 30, 1962, in Bessemer, Alabama, the eighth of Florence Jackson Bond’s 10 children born. A fan of the television show Ben Casey, Florence, who worked as a housekeeper, named her son Vincent Edward Jackson, after the show’s star, Vince Edwards.2 Young Vincent could never be confused with the program’s caring namesake; he was such a difficult youngster, that his family began referring to him as a boar hog. That eventually was shortened to Bo, and the nickname stuck.

Jackson inherited two traits from his absentee father, A.D. Adams, size and a terrible stutter. The size made him big, tough, and athletic, while the stutter made him a target of ridicule among other children. What he did not get from his father was discipline.

“We never had enough food,” Jackson wrote in his autobiography. “But at least I could beat on other kids and steal their lunch money and buy myself something to eat. But I couldn’t steal a father. I couldn’t steal a father’s hug when I needed one. I couldn’t steal a father’s whipping when I needed one.”3

While not a very good student at McAdory High School in McCalla, Alabama, he found an outlet for his anger and energy in sports. He won two state high-school decathlon titles, but it was his prowess on the football field and baseball diamond as a senior that attracted the scouts. He averaged 10.9 yards per carry as a running back, and smacked 20 home runs in a 25-game baseball season. The New York Yankees drafted him in the second round of the 1982 draft, but Jackson accepted a football scholarship to Auburn University instead.

Jackson had a legendary football career at Auburn. He rushed for 4,303 yards (still a school record as of 2016) with 43 touchdowns during his four years as a Tiger. His 1,786 rushing yards as a senior won him the Heisman Trophy as college football’s most outstanding player in 1985.

Yet, as good as he was at football, his goal was to play professional baseball. “My first love is baseball,” he said, “and it has always been a dream of mine to be a major league player.”4

Baseball scouts thought Jackson could make that dream come true. After watching him play on April 13 and 14, 1985, one scout wrote: “A complete type player with outstanding tools; can simply do it all and didn’t even play baseball last year. A gifted athlete; the best pure athlete in America today.”5

As highly regarded as he was, Jackson’s baseball career was almost derailed by an NCAA rules violation, a violation he felt was caused deliberately by the Tampa Bay Buccaneers, who planned to draft him number 1 in the NFL draft. Prior to the draft, they flew Jackson to Tampa in owner Hugh Culverhouse’s private jet for a physical examination. Even though Buccaneer officials told Jackson that it was within NCAA rules to accept the flight, it was nonetheless a violation. Jackson was suspended for the second half of his senior baseball season.

“I think it was all a plot now, just to get me ineligible from baseball because they saw the season I was having (after hitting .401 in 1985, Jackson was batting .246, with 7 home runs and 14 RBIs in 21 games in 1986) and they thought they were going to lose me to baseball,” he said in an ESPN documentary on his life. “(Like) if we declare him ineligible, then we’ve got him.”6

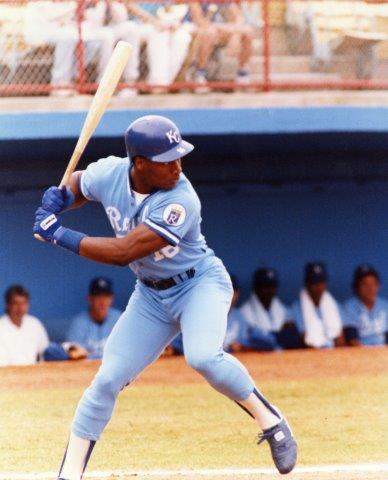

If it was a plot, it failed; the Bucs selected Jackson first overall in the 1986 NFL draft, but he declined their offer of a four-year deal worth between $5 million and $7 million, opting to play baseball instead. The Kansas City Royals chose Jackson in the fourth round of the 1986 major-league draft. (The California Angels had drafted him in 1985, but he didn’t sign with them, either.) While his contract with the Royals was not as lucrative as what the Buccaneers offered, Jackson still inked a solid deal, three years for $1 million.

The Royals sent Jackson to the Memphis Chicks, their affiliate in the Double-A Southern League, where he performed poorly at the plate early on — he had a .105 average after 10 games — but Chicks manager Tommy Jones wasn’t concerned. “Prior to (Jackson’s) first game, I said it would take three weeks for him to get comfortable and to adjust to life in baseball,” Jones said. “After three weeks, I felt we could make some evaluations. Until then, I don’t think it would be fair.”7

That approach proved wise, as Jackson improved steadily. After 53 games, his batting average had risen to .277, with 7 homers and 25 RBIs. These numbers prompted the Royals, having an offyear after winning the World Series in 1985 (they finished with a 76-86 record), to call him up on September 1, when major-league teams could expand their rosters. He made his debut on September 2, playing right field against the Chicago White Sox, and getting his first major-league hit off 41-year-old Steve Carlton. His first home run came 12 days later when he hit a solo blast in the fourth inning off Seattle’s Mike Moore. Jackson remained with Kansas City for all of September, and hit .207 with two home runs and nine RBIs in 25 games.

Jackson left no doubt about his work ethic by how hard he trained for the 1987 season, his first full year with the Royals. He worked with Hal Baird, his Auburn baseball coach, in January, and even Baird noticed a difference in Jackson’s intensity. “He was far more diligent in his work habits,” Baird said. “I saw more dedication, more willingness to work, than I had ever seen before.”8

That preparation paid early dividends, as Jackson made the team after very nearly starting the season at Triple A. A few days before the season started, general manager John Schuerholz had decided to send Jackson to the minors for more experience, but then changed his mind after doing something he had never done before. “I talked to several of our veterans — George Brett, Hal McRae, Frank White,” Schuerholz said. “I had never done that before, but they told me they thought he could help us.”9

Jackson made Schuerholz look like a pretty smart guy in the season’s first few days. He went 4-for-5 with three RBIs in a 13-1 pasting of the Yankees on April 10. He followed that performance up with a game for the ages on April 14 against the Tigers. He went 4-for-4, with two home runs — including a grand slam — and seven RBIs in a 10-1 laugher over the Tigers. Two weeks later, Jackson got some interesting news when the Los Angeles Raiders chose him in the seventh round of the NFL draft.10 Naturally this sparked great media interest, so Jackson put a sign over his locker that read: Don’t be stupid and ask football questions. OK!”

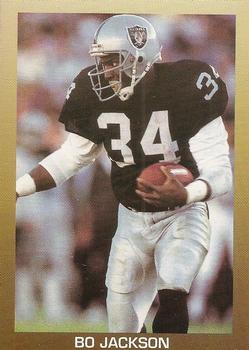

Regardless of the intelligence of the fourth estate, newspapers reported in July that Jackson was going to sign with the Raiders. Jackson responded to the speculation at a news conference when the Royals were in Toronto on July 11. “Any way you look at it, I have to do my job with the Kansas City Royals before I can do anything else,” he said. “Whatever comes after baseball season is a hobby for Bo Jackson.”11

Jackson’s teammates were not happy when he announced that he had reached terms with the Raiders on July 14 during the All-Star break. Even before he signed with the Raiders, some players felt he was only with the team because of his drawing power. There was also the sense that the front office treated Jackson differently than the other players. Most major-league contracts at the time included clauses prohibiting players from participating in off-field activities that could jeopardize their baseball careers, yet Jackson was allowed to play a violent contact sport. One anonymous Royal expressed his unhappiness by changing the sign above Jackson’s locker to read: “Don’t be stupid and ask any baseball questions.”

Fans weren’t happy, either, in part because the enmity between the Raiders and the hometown Kansas City Chiefs was palpable. When he took the field in the team’s first game after the season resumed, fans booed him lustily. Some even threw toy footballs that were printed with the words: “It’s a hobby.” Of course, fans being fans, they cheered him just as lustily when he made a spectacular tumbling catch in the fifth inning.

Coincidentally or not, Jackson’s play suffered in the second half of the season. He was benched for extensive periods because he was striking out at a prodigious rate — 27 strikeouts in 64 at-bats between July 16 and August 7. After hitting .254 with 18 home runs, 45 RBIs, and 115 strikeouts before the All-Star break, Jackson played in only 35 games in the second half, with four home runs, eight RBIs and another 43 strikeouts. He would have struck out 221 times if he had played in all 162 games.

While Jackson’s decision to play two sports was controversial, it also had its lighter moments. In a New Year’s Day 1987 column of tongue-in-cheek predictions, Kansas City Times writer Bill Tammeus wrote that Jackson would sign a contract to play with the National Hockey League’s Buffalo Sabres, then join the Ice Capades as a hobby. Jackson did receive — and this is true — an offer to play basketball with the Orange County Crush of the fledgling International Basketball Association, a league whose players could be no taller than 6-feet-4. The offer, which Jackson turned down, was a publicity stunt.12

After playing seven games with Los Angeles and scoring four touchdowns (including one on a 91-yard run against Seattle, the longest run from scrimmage in the NFL that season), Jackson returned to the Royals for 1988, but not before working with Auburn coach Baird again in the offseason. Baird was not impressed with what he saw.

“There’s a real need for some concentrated instruction,” Baird said. “I can’t believe he didn’t go to [Triple-A] Omaha last year. I think (the Royals) made concessions and misjudged him a little.”13

The media reported that Jackson faced competition for the left fielder’s spot from rookie Gary Thurman. It wasn’t really much of a contest, as Jackson batted .298, with 5 home runs and 12 RBIs in Florida, while Thurman hit .185 and struck out 16 times in 65 at-bats.14 Jackson went north as the Royals’ starting left fielder. He got off to a good start, too; after going 3-for-4 with a two-run homer and a stolen base in a 7-6 Royals win over Texas on May 16, teammate George Brett said: “Bo Jackson proves he belongs here. He still has a lot to learn, but he learns every time he goes out there.15

By the end of May Jackson was hitting .309, with 9 home runs and 30 RBIs. But then fate chose to intervene on June 1 when he tore a hamstring muscle running out a groundball. He missed 28 games, and his batting average began falling on his return. By season’s end it was down to .246. He hit 25 home runs, one behind team leader Danny Tartabull, and had 68 RBIs. His 146 strikeouts — including nine consecutive whiffs between September 16 and September 19 — were the fourth highest in the American League. He led junior-circuit left fielders in assists, with 12.

If Jackson has a favorite Beatles song, it may be “Come Together,” because that’s what happened for him in 1989. He started off hot again, so hot that by the All-Star break he had 21 home runs, just four shy of his 1988 total. Even his strikeouts created a sensation; he got his teammates’ attention when he broke a bat in two over his knee after striking out against the Twins on May 9. “Some jaws dropped and some eyes got real big in the dugout after that one,” said Royals coach John Mayberry.16

Jackson’s own jaw may have dropped when he saw the results of fan balloting for the 1989 American League All-Star team, as he led the American League, with 1,748,696 votes. He took full advantage of his moment in the sun, batting leadoff for the AL squad and going 2-for-4, including a 448-foot home run to center field and a stolen base as the American League defeated the National League 5-3. He garnered All-Star Game MVP honors, and the admiration of NL manager Tommy Lasorda.

“Bo Jackson was exciting, really” Lasorda said. When he hit (his home run), I thought it sounded like he hit a golf ball. He’s awesome and exciting.”17

But injuries disrupted Jackson’s season yet again when the regular season resumed. He missed 15 games between July 23 and August 8 with sore thigh muscles, an injury he had prior to the All-Star break. Unlike previous years, however, his numbers didn’t fall off a cliff, and he finished with 32 home runs, 105 RBIs (both career highs), 26 stolen bases, and a .256 batting average. He did lead the league in one category, with 172 strikeouts.

After his third season with the Raiders, in which he played in a career-high 11 games — he also had the longest run from scrimmage for the season, a 92-yard scamper against Cincinnati — Jackson started 1990 by fulfilling a promise to his mother. He had vowed to her that he would earn his college degree, and in January of that year he began taking classes at Auburn toward that end. He received a bachelor’s degree in family and child development in 1995. Sadly, his mother died in 1992 and never saw him graduate.

“I will be the first in my family to get a degree from a major college,” Jackson said. Hopefully, that will influence my younger relatives in the family as far as nieces and nephews to go on to college to try to be something or someone.”18

Jackson’s propensity for striking out went beyond the diamond and into the arbitration hearing room in February. He was seeking $1,900,001, but the arbitrator ruled in the Royals’ favor. Still, he earned a $1 million salary for the season, which, of course, followed the usual route of great start followed by serious setback. On July 17 he was on pace to hit .270 for the season with 39 home runs and 117 RBIs (albeit with 206 strikeouts) when he hurt his shoulder diving for a fly ball hit by fellow two-sport athlete Deion Sanders. He missed 38 games, but continued to hit well on his return, finishing with a .272 average, 28 home runs, and 78 RBIs in 111 games.

Jackson should have known from his arbitration experience that Bo didn’t know gambling, because in 1990 he bet once too often that the punishment he received playing football would not affect his baseball career. Jackson could have made sports history when he was selected to play in the NFL Pro Bowl after the season, which would have made him the first athlete to play in all-star games in two different sports. That was not to be, however, as he suffered a hip injury in a Raiders 20-10 playoff win over the Cincinnati Bengals on January 13, 1991, when he was tackled after a 34-yard run. He didn’t play in the AFC Championship Game against the Buffalo Bills — which was probably just as well because the Raiders lost 51-3. He never played football again.

Jackson and the Royals managed to avoid an arbitration hearing when he signed a one-year, $2.4 million deal with the team for the 1991 season. The contract didn’t really matter, because his hip injury wasn’t getting any better. He had developed a condition called avascular necrosis, which meant that his hip cartilage and bone were deteriorating. When spring training came around, he was still walking around on crutches and clearly unable to play. The Royals placed him on waivers on March 18.

Jackson wasn’t out of work long enough to apply for unemployment benefits. On April 3 he signed a three-year, $8.15 million contract with the Chicago White Sox, although “only” $700,000 was guaranteed. White Sox owner Jerry Reinsdorf likened the signing to buying an insurance policy. “It’s like life insurance,” he said. “You pay the premium, the premium is gone. But if it turns out you die, your family is very happy you had the insurance. If he comes back, we’ll be thrilled.”19

Jackson carried out his rehabilitation under the supervision of the White Sox medical staff. They gave him permission in mid-June to walk without the crutches he had been using since suffering the injury. A month later he started taking some batting practice and did some soft throwing. His workouts continued through August, then on August 25 he began a six-game minor-league rehabilitation assignment. Finally, on September 2, Jackson played his first game of the season against, ironically, the Royals. He went hitless in three at-bats as the DH, but drove in a run with a sacrifice fly. He played in 23 games, hit three home runs and had 14 RBIs, all at the DH spot.

Jackson was very happy to have returned to the field but the following offseason was full of bad news for him. On October 10 his football career effectively ended when he failed a physical given by the Los Angeles Raiders doctors. He made it official one month later when he announced his retirement from football. He joined the White Sox for spring training, but it was evident early on that he was not ready to play. The bat was there, but he wasn’t going to be much good on the basepaths. “I have to say if my running was like my hitting I’d be satisfied,” Jackson said. “But I’m not. I’m very down on myself for the way I’m running.”20

Jackson had his damaged hip replaced with a prosthetic ball and socket in Chicago on April 4, 1992. The prognosis was that he would be able to run after he recovered from the operation, but not at the level of a professional athlete. Jackson didn’t listen to the prognosis. “Medical and athletic experts figured Jackson would not be heard from again,” wrote Ron Flatter. “Apparently there were no Bo Jackson experts to be heard.”21

Jackson let nothing stand in his way from getting back on the ballfield, even his mother’s passing on April 27. His rehab was carried out under the watchful eye of White Sox trainer Herm Schneider, and although progress was slow, it was steady. Even with several hours a day of exercise and training, he walked with a limp until July, and didn’t begin his running program until January. Amazingly, he was ready to go for spring training, and on March 4 played his first baseball game in more than a year, going 1-for-3 in an 11-10 loss to Pittsburgh. His status with the White Sox wasn’t confirmed until the team finally decided to keep Jackson on March 24.

One might wonder why Jackson would put himself through all that work and discomfort — after all, he didn’t need the money. The answer lies in a promise he made to his mother. Before she died, she asked if he was attempting a comeback. He said that if he did, his first hit would be for her. On April 9, 1993, he faced a pitcher in a regular-season game as a pinch-hitter in the bottom of the sixth inning. Facing the Yankees’ Neal Heaton, he took the first pitch for a strike, then deposited the next pitch over the right-field wall for a home run.

“Lucky for me and unfortunately for the pitcher, I hit a home run,” Jackson recalled. “But that hit meant more to me than anything, because I kept my word, my promise, to my mom. I could have retired that night.”22

Jackson didn’t retire that night, but went on to play in 85 games that year, both in the outfield and at DH. He smacked 16 home runs, batted in 45 runs and hit .232. He also made his only career appearance in the postseason, going 0-for-10 with six strikeouts as the White Sox lost the ALCS in six games to the Toronto Blue Jays.

Jackson’s offseason was busy. His remarkable comeback from the hip-replacement surgery, and the intense effort he put in to attain that achievement, was honored when he won both the Tony Conigliaro Award and The Sporting News American League Comeback Player of the Year Award. (Andres Galarraga won in the National League.) On the playing side, Jackson rejected an offer of salary arbitration by the White Sox, choosing instead to take the free-agent route. He signed with the California Angels, the team that first drafted him in 1985.

Jackson had a good season in a part-time role for California, playing left and right field and at DH. He appeared in 75 games and batted a career-high .279, with 13 home runs and 43 RBIs in 201 at-bats. One of his season highlights was a five-RBI day at Detroit on May 26. But even before his season was cut short by the players’ strike, he began to talk about retiring. “When I left college, my lifelong goal was to be retired from professional sports when I was 34 years old (he was 31 at the time),” he said. “Because I don’t think I’ll start living until after that.”23

Jackson ended up retiring even sooner than that. The strike delayed the opening of spring training in 1995, and once it resumed, Jackson, who was a free agent, received calls from a few teams, but decided enough was enough. “I got to know my family [during the strike],” he said in explaining why he retired. “That looks better to me than any $10 million contract.”24

After retiring from sports, Jackson began working in numerous business and charitable activities. As of 2016, he ran a training complex for athletes in Lockport, Illinois. Among his charitable endeavours is the Bo Bikes ’Bama campaign. Tornadoes can cause devastating damage in Alabama, so every year he, his celebrity friends, and other participants cycle across his home state to raise money for the construction of community storm shelters.

Jackson and his wife, Linda, as of 2016 lived in Chicago and have two sons Garrett and Nicholas and a daughter Morgan.

Last revised: September 5, 2017

This biography appears in “Overcoming Adversity: The Tony Conigliaro Award” (SABR, 2017), edited by Bill Nowlin and Clayton Trutor. It also appears in “Kansas City Royals: A Royal Tradition” (SABR, 2019), edited by Bill Nowlin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author used the following:

Auburntigers.com.

ESPN.com.

Footballdb.com.

Observer-Reporter (Washington, Pennsylvania).

Pro-football-reference.com.

Sports Illustrated.

Stutteringhelp.org.

Swaine, Rick. Baseball’s Comeback Players: Forty Major Leaguers Who Fell and Rose Again (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2014).

Notes

1 Thorpe played six seasons in the majors and eight years in the NFL.

2 Ben Casey was a medical drama televised on ABC from 1961 to 1966.

3 Ron Flatter, “Bo Knows Stardom and Disappointment,” espn.go.com.

4 Ibid.

5 Matt Snyder, “Bo Jackson’s 1985 Scouting Report (Hint: He was good at baseball),” cbssports.com, May 7, 2013.

6 Greg Auman, “When Bucs Blew It By Drafting Bo Jackson,” Tampa Bay Times, April 24, 2015. The incident left Jackson with a bad taste in his mouth, and he warned the Buccaneers that drafting him would be a waste of a pick. The Buccaneers nevertheless chose him number 1 overall in the NFL draft, but he never signed with them.

7 “Bo’s Slow Start Doesn’t Concern His Manager,” The Tennessean (Nashville), July 10, 1986: 7-E.

8 “Jackson Leaves Almost All in Awe,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 19, 1987: 4F.

9 John Sonderegger, “Heirs Apparent: Jackson Gets Into Swing With Royals, Big Leagues,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, May 10, 1987: 11F.

10 Jackson was eligible for the 1987 draft because he did not sign with the Buccaneers in 1986.

11 ESPN Sportscenter, July 11, 1987. Jackson was often criticized as being arrogant for referring to himself in the third person. In fact, he was using a speech therapy technique he learned to prevent stuttering.

12 According to the Association for Professional Basketball Research (apbr.org), the International Basketball Association existed from 1988 to 1892 as the World Basketball League.

13 Rick Hummel, “Classy Horton Not Bitter Over Being Traded,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, February 14, 1988: 3G.

14 Thurman ended up playing in 424 major-league games over nine seasons.

15 “Jackson Continues Hot Pace,” Constitution-Tribune (Chillicothe, Missouri), May 17, 1988: 6.

16 Bill Coats, “Eye Openers,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, May 13, 1989: 2C.

17 “Royals’ Bo Jackson Is MVP in American League Victory,” Macon (Missouri) Chronicle Herald, July 12, 1989: 2.

18 Marsha Sanguinette, “Eye Openers,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch January 20, 1990: 6C.

19 Murray Chass, “White Sox Decide to Gamble on Bo Jackson,” New York Times, April 4, 1991. Note that baseball-reference.com lists his 1991 salary at $1,010,000.

20 Bill Madden, “Bo Jackson’s Baseball Career Appears Over,” Southern Illinoisan (Carbondale, Illinois), March 7, 1992: 4B.

21 Ron Flatter, “Bo Knows Stardom and Disappointment,” espn.com.

22 Lindsay Berra, “#TBT: Bo Jackson Misses a Full Season, Homers in First At-Bat,” mlb.com, April 9, 2015. Jackson later had the ball bronzed and placed it on his mother’s grave.

23 Mike Terry, “Bo Knows Life After Baseball,” San Bernardino County (California) Sun, July 10, 1994: C1.

24 “Well What Do You Know?,” Bo Retiring from Baseball,” The Tennessean, April 4, 1995: 6C.

Full Name

Vincent Edward Jackson

Born

November 30, 1962 at Bessemer, AL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.