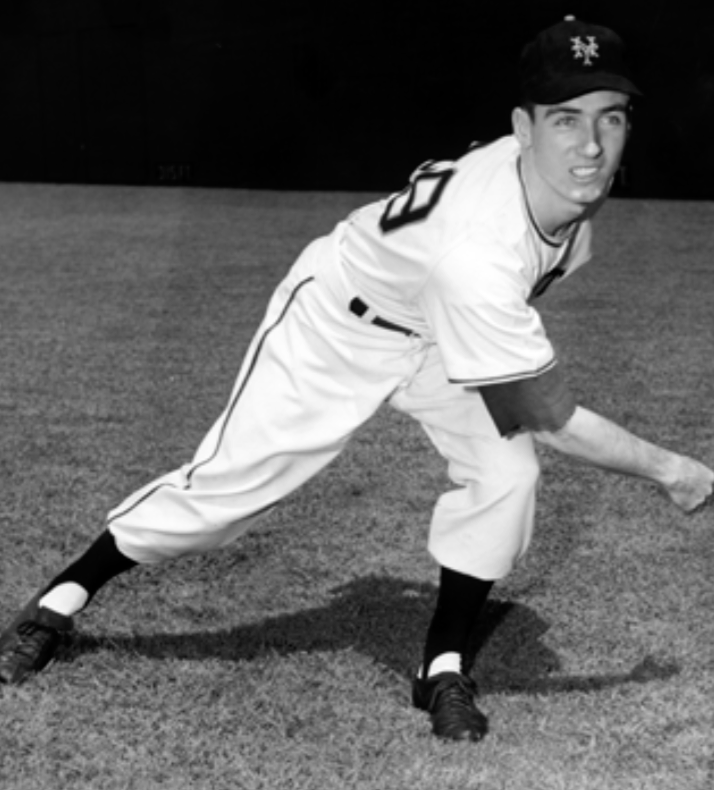

Al Corwin

Few jobs can match the excitement, adulation, and income that come with a spot on a major-league roster. Some old ballplayers inevitably seal themselves in amber, forever living vicariously through the men they used to be. The New York Giants’ Al Corwin was different. For him the game was “more paycheck than passion,” as one author put it.1 When it was done, it was done. Although Corwin’s pitching rėsumė was admirable by any measure, he moved on without regret and forged a career in business that far exceeded any heights he had achieved on the diamond.

Elmer Nathan “Al” Corwin, Jr. was born on December 3, 1926, in Newburgh, New York, a prospering industrial town about 60 miles up the Hudson River from New York City. He came from a line of successful small-town entrepreneurs; his grandfather operated a grocery store, while his father, Elmer Sr., founded a bus line shortly after World War I in the nearby town of Modena. Later his father owned a silk mill and a small hotel and, like many leading citizens of his day, was involved in fraternal organizations like the Odd Fellows, the Masons, and the Elks.

Al’s mother, Sarah, attended a business college and worked as a stenographer for a time. According to his older sister, Harriet Conklin, their mother was exceptionally patient and easygoing. “I don’t think we were ever really punished,” she said.2 Elmer and Sarah divorced when their son was 10. Although the trauma of a divorce can leave lasting scars on a child, Corwin apparently weathered it as well as could be expected. He had a large network of aunts and uncles nearby, and they provided critical emotional support.

Al was one of those special kids who seemed to excel at anything he did. His sister described him as “the marbles champion of Newburgh.”3 He also won a local speed-skating title and played four sports in high school. In his senior year at Wallkill High in Modena, “Junior Corwin,” as the local newspaper dubbed him, pitched his club to the North Orange Southern Ulster League championship.4

Upon graduation in 1944, Corwin, eager to join the war effort, signed up for the Naval Air Corps. Over the next 26 months, while stationed in San Diego and Panama, he flew reconnaissance missions on a seaplane, scouring the Pacific Ocean and Gulf of Mexico for enemy submarines lurking off the coast. After mustering out of the Navy in 1946 he remained out west and attended Pasadena City College (Jackie Robinson’s alma mater) on the GI Bill while toiling in a grocery store to pay the bills.

Although he was a good high-school pitcher, Corwin gave little thought to playing professionally. When the college’s baseball coach asked him to go out for the team in the spring, he showed up, twirled three no-hit innings in an exhibition game, and then walked away. “I was working from 8 to 4, attending night school, and only had an hour and a half daily to myself,” Corwin told a sportswriter. “He even offered to find me some little job that’d pay my expenses, but I saw nothing in baseball for me and turned him down.”5

Still, the game wouldn’t let him go that easily. In October Corwin’s roommate told him about a tryout camp the New York Giants were running just down the road in Monrovia, California. On a whim, he gave it a shot. Even though he had grown three inches in the service, he still wasn’t much to look at — a spindly 6-feet-1 and 160 pounds. But he threw hard and he threw strikes, and scout Mickey Schrader saw enough potential to sign him to a contract for the 1948 season.

Elmer Sr., ever the businessman, was appalled. “My father said, ‘Don’t you read the papers? Do you mean to say you signed up without a bonus?’ It had all happened so fast I hadn’t thought about money.”6

The 21-year-old side-arming right-hander began his professional career in the Class C Sunset League at Reno (where he drove the team bus for an extra $25 a month). On the surface, he enjoyed a brilliant year, racking up a league-leading 26 wins against just nine losses with an ERA of 3.54, third-best in the circuit. Home plate was a moving target sometimes; he walked an average of five men per nine innings pitched. But his 251 strikeouts in 280 innings suggest that when he got the ball over, he was tough to beat.

Class C baseball, though, was supposed to be a training ground; the Reno ballclub let Corwin get by on raw ability. “No one really taught me much,” he said. “Tommy Lloyd, the manager … told me to concentrate on controlling my fastball.”7 That wasn’t bad advice as far as it went; however, what Corwin also needed was a secondary pitch, something he could mix in with his heater. He didn’t pick that up at Reno. In fact, he really never developed a changeup or breaking ball that he could rely on.

Nevertheless, Corwin proceeded stepwise through the Giants’ chain, ascending to Class B Trenton in 1949 (15-11 with a 3.03 ERA) and then to Class A Jacksonville, where he got smacked around a bit in 1950 (9-18 with a 4.57 ERA). Despite those ugly numbers, the Giants promoted Corwin to Ottawa of the International League, where he opened 1951 in the bullpen. He continued to struggle until manager Hugh Poland moved him into the rotation in June.

It wasn’t long before the parent club, in second place but well behind Brooklyn, found itself desperate for a jump-start and in search of a fresh arm. After an exhibition game in Ottawa in July, manager Leo Durocher asked his pitching coach, Frank Shellenback, to stay behind for a few days and see if anyone caught his eye.

Shellenback observed Corwin during a start against the Brooklyn Dodgers’ International League club, the Montreal Royals. It was the first time he had seen Corwin throw, but the young man passed all the tests. “The first thing I liked about him was his fastball. It was alive,” Shellenback raved. “Then I liked the way he fought back when he was hit. … You can learn more about a pitcher when he is in a jam than you can when everything is breaking right for him.”8 When the two men spoke after the game, Corwin further impressed the old coach with his poise and intelligence. Shellenback reported back that he had found his man.

The recommendation raised some eyebrows among the Giants brass. Although he sported an outstanding 2.47 ERA, Corwin’s record was just 2-4; the safer choice would have been Alex Konikowski, who was pitching well and had already appeared in 22 games for New York in 1948. However, Shellenback was convinced that Corwin could get through the league a couple of times before opposing hitters adjusted to his side-arm delivery. On July 18 Poland pulled the 24-year-old Corwin aside and informed him that he had gotten the call.

Corwin hastily crammed his glove, jockstrap, shoes, and underwear into a duffel bag, left his ’47 Pontiac with a teammate, and hustled to the airport. A thunderstorm forced his plane to touch down in Albany at 1:00 A.M., so he didn’t arrive at LaGuardia Airport until late the next morning. When he did, he discovered that the airline had lost his bag.

Exhausted, Corwin dragged himself into a cab for a short ride across the rain-slicked Triborough Bridge to the Polo Grounds, where clubhouse man Eddie Logan awaited. The next hassle was finding a uniform that fit; Corwin’s waist was 31 inches — even the smallest thing on Logan’s rack billowed like a tent. With that day’s scheduled doubleheader washed out, Logan took time to introduce the newest Giant to his teammates and manager. Corwin long remembered his first whiff of Durocher’s Fabergė cologne — the heady scent that, in his mind, forever symbolized New York and the big time.

As it happened, that also was the day when Durocher first revealed to the club that an electrician had rigged up a primitive device that would enable the Giants to steal the opposing catcher’s signs and then relay them to the hitters. Yet despite this frenzied, bizarre introduction to the major leagues, Corwin was unfazed. “He just kind of rolled with it,” said Joshua Prager, who interviewed Corwin nine times while researching his book, The Echoing Green. “The fact that Durocher was this incredibly foul-mouthed guy, he got a kick out of it. Oh, well, here we are in Gotham and they steal signs here? That’s interesting. My jersey doesn’t quite fit me? Well, that’s OK.”9

Durocher gave Corwin the ball on July 25 in Pittsburgh. He blanked the Pirates on three hits through six innings in his debut before hitting the wall in the seventh. “I wasn’t nervous but I got tired.” As fatigue set in, he elevated his pitches. After back-to-back singles to lead off the seventh, Joe Garagiola homered to tie the game, and one batter later Corwin was gone. Two starts later, on August 1, he was able to finish the job, scattering seven hits in a 2-0 shutout of the Cubs and leaving Chicago manager Phil Cavarretta impressed. “He’s faster than [Sal] Maglie.”10

Corwin made five starts and four relief appearances during that fateful August and was effective nearly every time out. He went 5-0 with one save and a 2.27 ERA that month, including a pair of complete-game victories over the Cubs and one over the Phillies. He played a huge role in New York’s 16-game winning streak, which slashed the Dodgers’ lead from 13 games down to five in the span of just two weeks.

Durocher called Corwin “the coolest kid I’ve ever seen come up,”11 and predicted, “This kid is going to be a great pitcher. Nothing bothers him.”12 An unnamed teammate suggested that the youngster’s self-assurance had rubbed off on the entire club, saying, “He was the only one attending to his business without any extra worries. Everyone has become like Al Corwin and loosened up.”13 In reality, Corwin was no less jittery and emotional than any other rookie in his spot would have been; he just concealed it better than most. “[I am] so damn happy about winning up here,” he exclaimed to a reporter in a moment of candor. “Excited inside, you know what I mean?”14

Corwin pitched poorly in a 6-3 loss to the Phillies on September 3, his only defeat of the season. From that point on, Durocher used him sparingly, instead leaning heavily on his core of three veteran starters — Maglie, Larry Jansen, and Jim Hearn — as New York finally caught Brooklyn on the next-to-last day of the regular season and then beat them in a best-of-three playoff on Bobby Thomson’s historic home run.

Corwin’s only appearance in the Giants’ six-game World Series loss to the New York Yankees came in mopup duty in Game Five. He inherited a bases-loaded, one-out mess in the seventh inning with his club down 10-1. After unleashing a wild pitch and surrendering a two-run double to Joe DiMaggio, he settled down to pitch a 1-2-3 eighth.

The offseason was an eventful and life-changing one for Corwin. His father had been hospitalized with stomach ulcers throughout the World Series and died on October 18 as a result of complications from surgery. A much happier day came shortly thereafter, when he met a woman named Patricia McMahon at the Hotel Newburgh. That was where she and her mother had lunch every Wednesday. She had no idea that Corwin was a ballplayer but her father, a die-hard Dodgers fan, knew the name all too well and was eager to meet the young man. Al and Pat soon were engaged, and were married January 25, 1953, in Newburgh.

Corwin arrived at spring training in Phoenix in 1952 determined to master a curveball, but opposing batters teed off on him. The Giants optioned him to Triple-A Minneapolis, where his struggles continued. The right-field fence at the Millers’ Nicollet Park loomed just 279 feet from home plate, and he let that get into his head. “Corwin tried to get the batters to hit away from the wall and found himself changing his whole style of pitching,” according to Giants scout Tom Sheehan. “The kid got so fouled up that he lost his control, walked a lot of people, and was frequently in trouble.”15

Corwin’s record was just 8-11 but he did lead the American Association in strikeouts into August. That was sufficient to earn a recall to New York to take some of the bullpen load off an overburdened Hoyt Wilhelm. Corwin again pitched extremely well in a tense pennant race — 6-1 with a pair of saves and a 2.66 ERA in 21 games, including seven starts — although this time the Giants couldn’t quite catch the Dodgers.

That good work was not good enough for Durocher, though, who, in the words of Joe King of the New York World-Telegram, “treats Corwin as a precocious child who has not quite lived up to papa’s expectations.”16 Durocher always had his favorites. Corwin was not one of them, which perhaps is not surprising. The men had as much in common as a sewing machine and a tomato — Corwin was composed and thoughtful; Durocher, a high-living, libidinous hustler. The skipper wasn’t shy with his criticism. “[W]hen I farmed him down early this year, I told him to develop another pitch and he didn’t do that. He’d be twice as good with a surprise pitch to throw in with that curve and fastball.”17 Moreover, he was constantly harping on the slender Corwin’s perceived lack of stamina. “Even when he relieves he needs two days’ rest” — an odd remark coming from the man who sent Corwin to the hill six times in seven days following his recall in 1952.18

Corwin conceded the point about his repertoire. “I know my shortcomings as a pitcher,” he offered to a reporter in the offseason. “I’ve only begun to learn this trade. I’m chiefly a thrower now. Perhaps in the majors I have won because there’s been great fielding behind me and good catching back of the plate.”19

Corwin was with the Giants throughout all of 1953, his only full season in the major leagues. He worked mostly out of the bullpen but, despite a 6-4 record, was not terribly effective. His 4.98 ERA was well above the league average and he walked more people than he struck out. The season did yield one moment that Corwin would crow about for years — a home run he hit against Brooklyn, the second of back-to-back-to-back round-trippers off the Dodgers’ Russ Meyer. (Corwin was a fine athlete. He handled the bat well, especially in the minors, and Durocher frequently employed him as a pinch-runner.)

It was around this time that Corwin’s shoulder began to go bad. “No papers reported my arm troubles and in those days, no one complained,” he said. “We just kept pitching.”20 He again split the 1954 and ’55 seasons between Minneapolis, where he was mostly a starter, and New York, where he had become exclusively a reliever. He pitched just 20 times for the Giants in 1954, going 1-3 with a 4.02 ERA, and did not appear in their four-game World Series sweep of the Cleveland Indians. At the start of 1955, Durocher seemed even more exasperated with him than usual: “How can I count on Corwin? He is never ready. If he hasn’t got something wrong with him he has something else wrong with him. When is he ready to pitch?”21 Laboring through the pain that season, Corwin was hit hard at Minneapolis and made just 13 appearances with New York.

The sun was beginning to set. Corwin underwent shoulder surgery in the spring of 1956 and was never the same. The Giants finally gave up on him in May 1957, setting him off on a 3½-year Triple-A odyssey that took him from the Orioles system to the Tigers chain and finally to the Kansas City Athletics organization. He went 12-8 for two clubs in 1958 and 10-12 with a respectable 3.63 ERA for Dallas in the American Association in 1959, but by this point his flaming fastball was gone, along with his chances of ever making it back to the bigs. Weary of moving and with his son approaching school age, the 33-year-old Corwin called it a career at the conclusion of the 1960 season. He finished with a major-league record of 18-10 and a solid 3.98 ERA in 117 games.

Naturally, it was disappointing for Corwin to walk away from the game, but according to his wife, Pat, he knew it was time. “It wasn’t something he lost sleep over,” she said. “He just wasn’t like that.”22 Yet, it took him a while to figure out the next chapter. He wasn’t trained to do anything other than throw a baseball. His father-in-law’s company hired him for some construction work, but Corwin quickly decided the best way to move on was to get out of New York: “I didn’t care to live in my hometown where everybody greeted me each morning with, ‘Gee, if you hadn’t hurt your arm and needed that operation, just think how long you could have played.’”23

Instead, the Corwins relocated to Southern California, where Al took a sales position with the spirits company Seagram’s. It was the kind of job coveted by former athletes and it certainly gave him some valuable experience. Unfortunately, the work basically required him to sit in bars half the night, spinning yarns about the good old days. That wasn’t his scene.

In 1963 he got another sales gig, this one with faucet manufacturer Moen, where he promoted the brand to contractors who specialized in large-scale new-home development. Corwin had a likeable, trustworthy personality. He loved meeting people, taking them out on the golf course, and getting to know them. These traits made him a gifted and highly successful salesman. Moen transferred him to Chicago in 1969, elevated him to regional manager, and put him in charge of sales for 11 Midwestern states.

Corwin’s reputation spread through the industry, and in 1977 he was lured away by a competitor, German-based Grohe. As president of Grohe America, Corwin helped to introduce the brand to the already-crowded US market. Grohe was selling high-end stuff in an era when most Americans perceived kitchen and bath fixtures as commodities; it would not be an easy road and it required a huge shift in consumer thinking. “The presidents of two major faucet companies told me I had made the mistake of my life,” Corwin remembered. “Nobody sold expensive faucets in those days.”24

When Corwin assumed the presidency, US sales were virtually nil. But over the next 18 years, thanks to his strategic acumen and preternatural marketing instincts, Corwin established Grohe as the Mercedes-Benz of faucets — a high-end product born of high-quality German engineering. He also made significant inroads into Canada and pushed through construction of a 90,000-square-foot office, manufacturing, and warehouse complex in Bloomingdale, Illinois, in the Chicago suburbs. By the time his successor, Bob Atkins, stepped down in 2004, Grohe America was the corporation’s leading subsidiary in the world. “We used all of what Al taught me and expanded it,” according to Atkins. “We made the headquarters a lot of money, but it was all because of him.”25 Corwin came to be regarded as a visionary. A 2004 publication named him one of the industry’s top innovators of the previous 50 years, alongside such recognizable names as Albert Moen, Herbert Kohler, Jr., and Roy Jacuzzi.26

Corwin was a beloved figure at Grohe America. He looked out for his people, instituting a generous pension plan and a smorgasbord of perks. At sales meetings he was the head cheerleader. “When he spoke, you listened,” declared Atkins. “He believed in what he said, and he was going to lead you. You knew he would be right there in front of you.”27 If one of his people had a concern, Corwin was not hard to find. He visited the shipping dock all the time and ate his brown-bag lunch alongside everyone else in the employee cafeteria. At the same time he cut an imposing figure, an attractive dark-haired man with a stentorian voice, immaculately dressed every day, his big 1954 World Series ring glimmering on his left hand.

The unflappable demeanor for which Corwin was known during his playing days served him well as a Grohe executive. His life there was an unending series of battles with his belligerent bosses. “Al taught me to insulate the employees, the sales reps, and our customers from the German headquarters,” said Atkins. “They were very abusive. They would scream and holler and yell on the last day of every month because they wanted more business. Then you had to turn around and face everybody in the United States and say everything is great; they love us. You can’t imagine what it was like.”28

Corwin didn’t talk about his baseball days unless someone asked him, which people seldom did. But they knew. Atkins recalls inviting Corwin to play catch at a company picnic. It had been years since he had picked up a ball, but he still had the touch. “He wound up and threw a ball and almost knocked me on my rear end. No one could believe he could throw a ball that hard.” At his retirement party, Corwin got a chuckle out of a card created by one of his staff. On one side was an image of George Washington with a Grohe faucet in his hand; on the other side was a reproduction of one of Corwin’s old baseball cards, with the caption, “Our Founding Father.”

Corwin retired in 1996, although he attended Grohe sales meetings for a couple of years afterward simply because people still wanted to see him. He and Pat split their time between a condo in Florida and their longtime home in Geneva, Illinois (an abode that Atkins described as, “Absolutely immaculate. I mean, impeccable. I don’t think I’ve ever seen a house like his”).29 He was on the tennis court and the golf course constantly and was a major fundraiser for some nonprofits, including the Make-A-Wish Foundation. Corwin was not sentimental about baseball. He didn’t stay in touch with many former teammates and wasn’t big on saving memorabilia, but he was thrilled when the Giants flew him and all of his living 1951 teammates to San Francisco for a reunion in 2002.

In the early 2000s, Corwin’s dermatologist discovered a worrisome growth on his right shoulder. A biopsy revealed that it was malignant, and further tests showed the cancer already had spread to his lymph nodes. Corwin had blue eyes and fair skin. When he was a kid, he spent a lot of time outdoors without a shirt, and his shoulders often were sunburned in the summer. The doctors figured that that might have been when the melanoma time bomb had begun to tick.

Fortunately, Corwin was active and feeling energetic almost right to the end. It was only in the final couple of months that his health took a sudden turn for the worse. In his last weeks, he had come to grips with his fate, but the toughest part was the sense of isolation. He was such a people person, but he couldn’t bear for old friends and colleagues to see him so sick. Corwin died at home in Geneva on October 23, 2003, at the age of 76. He was survived by his wife of 50 years; his son, Glen; his daughter, Nancy; his sister; and a stepbrother.

Corwin’s memorial service was packed to overflowing, with mourners who couldn’t squeeze in left to linger in the parking lot. Interestingly enough, Bob Atkins’ eulogy mentioned nothing about baseball. Rather, he focused on the soul of the man. “He was your best friend and he’d give you the shirt off his back. And if you watched, listened, and paid attention, you could learn more from Al than any ten people I know. He was one of those very special people. … I’ll never forget him.”30

The author thanks Gabriel Schechter of Cherry Valley, New York, and the Historical Society of Newburgh Bay and the Highlands for their assistance.

Sources

Fehler, Gene, When Baseball Was Still King: Major League Players Remember the 1950s (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2012).

Prager, Joshua, The Echoing Green: The Untold Story of Bobby Thomson, Ralph Branca, and the Shot Heard Round the World (New York: Pantheon, 2006).

Rosenfeld, Harvey, The Great Chase: The Dodgers-Giants Pennant Race (Lincoln, Nebraska: iUniverse, Inc., 2001).

Thomson, Bobby, with Lee Heiman and Bill Gutman; The Giants Win the Pennant! The Giants Win the Pennant!: The Amazing 1951 National League Season and the Home Run That Won it All (New York: Zebra Books, Kensington Publishing Group, 1991).

Chicago Tribune

Hudson Valley News

New York Journal-American

New York Post

New York World-Telegram

Newburgh (New York) News

Baseball Digest

Contractor

The Sporting News

Supply House Times

Baseball-Reference.com

Bob Atkins personal files, transcript of eulogy, November 1, 2003.

Bob Atkins, telephone interview with author, January 13, 2014.

Harriet Conklin, telephone interview with author, November 25, 2013.

Patricia Corwin, telephone interview with author, December 8, 2013.

Joshua Prager, telephone interview with author, December 19, 2013.

1] Joshua Prager, The Echoing Green: The Untold Story of Bobby Thomson, Ralph Branca, and the Shot Heard Round the World, 28.

2 Harriet Conklin, telephone interview with author, November 25, 2013.

3 Conklin interview.

4 Newburgh News, June 17, 1944.

5 Baseball Digest, February 1953.

6 Ibid.

7 Ibid.

8 New York Journal-American, March 13, 1952.

9 Joshua Prager, telephone interview with author, December 19, 2013.

10 Harvey Rosenfeld, The Great Chase: The Dodgers-Giants Pennant Race, 41.

11 The Sporting News, September 5, 1951.

12 New York Post, August 13, 1951.

13 Rosenfeld, 41.

14 New York World-Telegram, August 13, 1951.

15 New York Journal-American, August 13, 1952.

16 New York World-Telegram, August 11, 1952.

17 Ibid.

18 New York World-Telegram, August 18, 1953.

19 Baseball Digest, February 1953.

20 Gene Fehler, When Baseball was Still King: Major League Players Remember the 1950s, 31.

21 New York World-Telegram, April 8, 1955.

22 Patricia Corwin, telephone interview with author, December 8, 2013.

23 Supply House Times, April 1995.

24 Ibid.

25 Bob Atkins, telephone interview with author, January 13, 2014.

26 Contractor, July 2004.

27 Atkins interview.

28 Atkins interview.

29 Atkins interview.

30 Bob Atkins personal files, transcript of eulogy, November 1, 2003.

Full Name

Elmer Nathan Corwin

Born

December 3, 1926 at Newburgh, NY (USA)

Died

October 23, 2003 at Geneva, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.