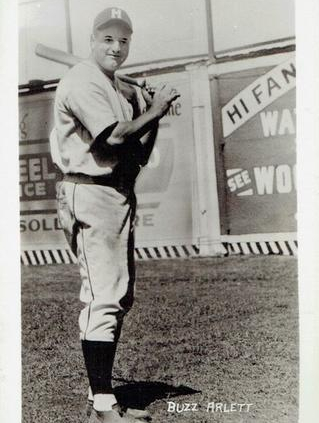

Buzz Arlett

Author’s note: Many a night, when I should’ve been doing my homework, I spent valuable time “studying” the encyclopedia of baseball. I especially became fascinated with obscure players having brief careers. I didn’t get far into the alphabet before coming across Buzz Arlett; how could someone with seemingly good numbers play only one season in the bigs? The reasons haunted me long enough to decide I had to know the story; here’s the story.

The country was mired in the torment of the deepening Depression. Herbert Hoover was in the White House; unemployment soared to 15%, while a disenchanted people sought any means available to divert attention away from the hardship of everyday life.

The country was mired in the torment of the deepening Depression. Herbert Hoover was in the White House; unemployment soared to 15%, while a disenchanted people sought any means available to divert attention away from the hardship of everyday life.

It was the spring of 1931 and scarce pennies were invested in leisure pursuits such as movies, radio and of course baseball. America was in the mood for a special kind of hero, a real-life Buck Rogers to divert their minds from troubled times.

Understanding the need for such diversion, newspapers of the day sought to lighten spirits with uplifting stories of human interest. Such a hero was found in the story of Buzz Arlett, who for a brief moment in the spring of that year, produced heroic exploits for a populace in trouble. It was the engaging story of an aging rookie who suddenly burst upon the major leagues with a thunderous bat and an engaging personality.

We don’t know what Buzz Arlett was thinking when he made his major league debut on April 14, but we do know it was the culmination of 13 long years in the minor leagues, following a path dotted with false hopes and devastating setbacks, while playing on the West Coast as one of the biggest stars in the “third” major league.

Russell Loris “Buzz” Arlett was born in Elmhurst, California, on January 3, 1899. He was the youngest of four sons born to German immigrant Beny and his English wife Lillian. Sister Evelyn rounded out the family.

Brothers Al, Harry, Leslie (Dick) and Russell were no strangers to the diamond. While growing up, it was common for the Arlett brothers to play ball from sunup till sundown. If a ball was unavailable, the brothers were known to use fruit, stones or anything resembling a sphere as a substitute. Buzz went through life with a scar on his nose, thanks to an errantly thrown rock. As an adult, Buzz happily recalled his joy in learning the 1906 San Francisco earthquake had leveled his elementary school, providing the brothers with lots of extra time to play ball.

In 1918, oldest brother Al was already a member of the Oakland Oaks when he departed for spring training at Boyes Springs, California. In need of a vacation, the Arlett family decided to accompany Al as he got into shape for the upcoming season. Buzz took time off from his job, wiring motors at thirty cents a day, to be with the family.

During early workouts, the team experienced a lot of injuries. Especially hit hard were the pitchers, hurting from an assortment of aching muscles and sore arms. Manager Del Howard didn’t have enough healthy pitchers for an inter-squad game, when suddenly a spectator named Buzz Arlett piped up with a solution to the manager’s problem.

Boldly announcing to the Oaks skipper “he was a ballplayer,” the youngster was told to suit up and take the hill. Pitching for the reserves versus the regulars, Buzz proceeded to mow down seasoned veterans with a dazzling assortment of spitters, fast balls and curves. This was how he earned his nickname: based on his ability to tear through the opposition like a human buzz saw!

After several impressive mound appearances, the 19-year-old was signed to a professional contract. He stood over 6′ 3″ tall and weighed in at a muscular 185 pounds. During the 1918 season, young Buzz would post a 4-9 record for the last place Oaks; he impressed both fans and management alike with his raw talent on the hill.

From 1919 to 1922, the young right-hander blossomed into the workhorse of the staff, posting an overall record of 95-71. In 1920 alone, he won 29 games, while toiling an exhausting 427 innings. In those days, the PCL played an elongated schedule often exceeding more than 200 games a season. The future seemed bright, as exuberant members of the press compared Arlett’s mound exploits to the likes of Walter Johnson and Grover Cleveland Alexander.

Major league teams started hovering around, including scouts from Detroit and Cincinnati. Detroit opted against pursuing the youngster, since his primary pitch was the recently outlawed spitball. In 1922, the Reds were interested in signing the young star, when his “gameness” became an issue; it seemed Buzz didn’t concentrate when contests were badly out of reach. Reds president Garry Herrman determined this to be a byproduct of toiling for a last-place club. Considering his overall ability, a change of scenery was probably just what the doctor ordered. Herrman directed his scouts to pursue the young prospect.

While the “ivory hunters” were jockeying for position, the massive number of innings pitched caught up with Buzz during the 1923 season, causing irreparable damage to his pitching arm. Admiring scouts were now scared away; a dejected Buzz thought his once promising career might never get back on track.

Buzz got tired of warming the pines, waiting for his arm to heal. He approached manager Howard and asked about playing the outfield. Arlett was already considered one of the better hitting pitchers in the league and was no stranger to pinch hitting assignments. Management approved the experiment, and the news shook Buzz from his depressed state.

The next problem was also related to his bum right arm: he couldn’t swing a bat. The right-handed hitting Arlett asked if he could practice hitting left-handed. An affirmative from the boss allowed Buzz to spend countless hours in the cage, practicing his portside swing. Adapting easily to the left side of the plate, Arlett soon began regularly patrolling the Oaks outfield. Buzz would continue as a “turn around” hitter throughout his career; arguably becoming the first power switch hitter in the history of the game.

Buzz responded in fine fashion, posting a .330 mark in 149 games as an outfielder. Major league scouts were astonished when they came to check the progress of his damaged throwing arm, only to find him blasting the opposition with his potent bat. Buzz was just a natural hitter, generating immediate results from both sides of the plate; however he didn’t take so easily to the outfield. While learning his new position, Buzz was awkward in his early days as a fly chaser, a fact not lost upon the scouts.

In 1924, the Cardinals sent a scout to watch Buzz in action. Arlett responded with a particularly bad day in the field. One fly ball even landed squarely on the head of the outfield newcomer. The scout abruptly ended consideration, surmising the big guy would lose more games with his glove than he’d win with his bat. Arlett would soon improve to become, at best, an adequate fielder; however, the reputation of being a poor glove man would persist.

The Reds were still interested. A letter to owner Herrman pointed out that his arm appeared to have improved; his fielding was great; he was smart on his feet; ran and hit well; but alas was temperamental and got down when his team was behind.

Buzz played some first base in 1924 while recuperating from an injury. His play around the bag was more than adequate for someone again thrust into a new position. Buzz put up more big numbers, contributing 33 home runs and a .328 batting average. The 33-homer mark led the Oaks in that offensive department; number two on the club came in with a total of 11 dingers. The 1925 season would be more of the same, as big Buzz punished Pacific Coast League pitching to the tune of a .344 average with 25 homers.

Buzz had a phenomenal year in 1926, hitting .382, with 25 home runs and an impressive 140 runs batted in. While amassing these numbers, a report was leaked that Buzz had been sold to Brooklyn. The sale never materialized, due mostly to an excessive dollar amount placed on the services of such a prized player, literally putting him out of the reach of prospective suitors.

The minor leagues were independent of major league ownership. In many cases, high minor league players were under contract to a team with no desire (or incentive) to sell valuable players. Often, owners would hold out trying to drive up bid amounts, later securing a premium dollar amount to fortify the team’s coffers.

Minor league players became stars in their own right and often earned salaries that exceeded the income of their big league brethren. Many minor league players were content with the system, enjoying the climate and lifestyle of cities not represented by major league baseball. Buzz Arlett was clearly such a player. He earned a high salary, and the Oaks, always a top team in attendance, appreciated the number of fans he put in the seats.

Nevertheless, press and fans alike lobbied for Buzz’s promotion to the big leagues. The sentiment persisted that Buzz had served the coast league well and now deserved a chance at the big show. News accounts reported: “although previously a little awkward in the outfield, he’s now . . . one of the best fielders; can make the long throws; is fast on the bases and a smart player; although he’s getting a little old!”

Buzz showed off his prowess in a July game when he cleanly fielded a single to right, came up throwing and nailed a runner at third. Second base was left uncovered; Buzz ran in, took a throw from the third baseman, and tagged out the batter trying to stretch his hit into a double.

Buzz was knocked unconscious in September when he made a running catch in right field. Diving into foul territory, he crashed headlong into the cement base of the bleachers, while holding onto the ball.

Nineteen twenty-seven was cause for celebration all around. Buzz gave up the single life. Marriage apparently agreed with the big outfielder, as he led the league with 123 RBI, hit 30 home runs, and posted a .351 batting average. Ivan Howard took over the managerial reins from his brother Del, and the Oaks won the Pacific Coast League pennant, their first in 15 years.

An event called “Buzz Arlett Day” was planned toward the end of the season. The big fellow was presented with an array of gifts, cash and even a brand new car. Local dignitaries, distinguished guests — and best of all even Buzz’s mom attended. Buzz won the fungo-hitting contest, but declined to address the crowd with a speech.

Manager Howard had a surprise awaiting his big star: With the pennant already secured, Buzz was going to take to hill and pitch the game to commemorate his day. Buzz proceeded to beat the Seals 12-6; allowing 10 hits and 3 runs, before being relieved. Buzz batted fourth and contributed two home runs to his winning cause.

Toward the end of the 1927 season, manager Howard, along with Coaches Joe Devine and Louie Guisto, commented to the news media that a play Buzz made in right field was perhaps the greatest catch any of the three had ever witnessed. After a long run, Buzz dove, made the catch and rolled several times before triumphantly rising to his feet with the ball secured in his glove.

Nineteen twenty-eight marked another fine season, with Buzz hitting .365 with 25 home runs and 113 runs batted in. The ’29 campaign was even better. Buzz chalked up 270 hits for an average of .374. His productive numbers included 39 homers, 189 RBI and 22 stolen bases. With these stats and numerous false starts, PCL president Harry Williams began to publicly express the pent-up rage of the Oakland fan base. Williams lobbied major league baseball, pleading with owners to get this guy where he belonged. It was readily acknowledged that spending his entire career in Oakland had slowed the advancement of Buzz Arlett.

Nineteen twenty-eight marked another fine season, with Buzz hitting .365 with 25 home runs and 113 runs batted in. The ’29 campaign was even better. Buzz chalked up 270 hits for an average of .374. His productive numbers included 39 homers, 189 RBI and 22 stolen bases. With these stats and numerous false starts, PCL president Harry Williams began to publicly express the pent-up rage of the Oakland fan base. Williams lobbied major league baseball, pleading with owners to get this guy where he belonged. It was readily acknowledged that spending his entire career in Oakland had slowed the advancement of Buzz Arlett.

Williams went on at length, expounding on Buzz’s hitting ability and deceptive speed for a big man. Claiming he was more than adequate as an outfielder, the league president pointed out that Buzz could handle first base too. He even went so far as to remind major league brass that Buzz was still listed as an eligible spitball pitcher, albeit in the Pacific Coast League. The pitch, illegal since 1920, was grandfathered to hurlers who pre-dated the ruling; Arlett’s arm had apparently recovered sufficiently for such a consideration.

Perhaps Williams should have lobbied Oaks ownership to revise the asking price for their biggest draw and star. Buzz became fed-up, too, with rumors of his big league potential never materializing. He took matters into his own hands by holding out and seeking a higher salary. Oakland began to realize that Buzz would cost more as years passed and his age would cause a decline in value.

Buzz ultimately signed again with the Oaks for the 1930 season. The latest club expressing interest was Brooklyn of the National League. Scout Joe Becker was dispatched to California by manager Wilbert Robinson, in search of another productive bat to insert into the Robins lineup. Becker was familiar with the circuit as a former Pacific Coast League umpire. He toured the league and scouted his list of prospective candidates, while Brooklyn remained in the hunt for the National League flag. He made his decision and Buzz Arlett was the player he wanted to sign. Suddenly disaster struck–in the form of an umpire’s mask!

Early in the 1930 season, the Pacific Coast League was experimenting with night baseball. In June, a series commenced at Sacramento, pitting the Solons against the Oakland Oaks, under newly installed lights at Moreing Field. The Oaks lost the opening contest, 8-0, amidst complaints from players regarding the lack of sufficient lighting.

Oakland won the next game, 10-9; however, an ill Buzz Arlett left the game early after striking out in his only plate appearance. The Oaks had a new manager in 1930 named Carl Zamloch. He removed Arlett from the lineup and sent his star outfielder back to the hotel for bed rest. The next day, Buzz was examined and admitted to the hospital. Toward evening, Arlett was feeling better while he listened to the game on a radio next to his bed.

With his team trailing, Buzz decided to get dressed, leave the hospital and head to the ballpark. The bench jockeys were already working hard when Buzz arrived late in the game. Buzz suited up and took his place on the Oakland bench, as players continued to razz home plate umpire Chet Chadbourne. Naturally, Buzz joined his teammates in riding the ump over blown calls.

For the second night in a row, benches cleared over pent-up frustration stemming from Chadbourne’s calls at home plate. Order restored, Chadbourne decided to toss Arlett, banishing Buzz to the visitors’ clubhouse. After the game, as players cleared the field, Arlett sought out Chadbourne, in the tunnel leading to the clubhouse. Buzz wanted an explanation and asked the ump why he was thrown out of the game. Without uttering a word, Chadbourne turned, reached over another Oaks player and viciously struck Buzz in the head with his heavy iron mask. The glancing blow struck Arlett just above the left eye.

Shocked and incensed over what happened, a bloody Buzz Arlett had to be restrained as he dove toward the umpire. Buzz was rushed back to the hospital, where he was listed in serious condition. The cut on his skull was bone deep and required 12 stitches to close; doctors were also concerned about permanent eye damage.

Manager Zamloch expressed dismay over the entire situation. He emphatically stated the umpiring was poor and naturally the players would react with razzing from the bench; however, nothing could possibly warrant such outrageous behavior from a member of the umpiring corps.

Both Arlett and Chadbourne were suspended pending a league investigation. Oakland players rallied around their teammate, adamant that Buzz had not laid a hand on the ump. A police officer who witnessed the fracas testified that Arlett was not the cause of the provocation. The league called a meeting of only the umpiring crew; members of the Oaks were not invited to attend and provide commentary on the events they had witnessed. Baseball commissioner Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis got a report of the incident and was upset at the thought of an umpire striking a player.

The Robins, still seeking to spark to their lineup for the balance of the 1930 season, withdrew their offer. A wounded Buzz Arlett recuperating in a West Coast hospital would certainly not be of any short-term help. The Dodgers signed Ike Boone.

Eventually, both Buzz and the umpire were reinstated. Arlett considered taking legal action against Chadbourne. Buzz maintained his innocence and even considered suing, to the tune of $10,000 worth of compensation, for an injury that could have permanently kept him out of the game. A fan letter to the league office further backed up Buzz’s claim that he had not provoked the attack. After almost eight years of false starts in becoming a major leaguer, Buzz could taste his chance, only to have it whisked away in a moment of rage.

Buzz stayed with the Oaks and slowly got back to his old self. He had trouble hitting from the right side while his left eye healed. Despite the missed time and accompanying mishap, Buzz would end the season hitting .361, with 31 homers and 143 RBI. One can only speculate what kind of numbers Buzz Arlett would have posted, as a member of the Dodgers, during a remarkable offensive year like1930. The addition of his bat into Ebbets Field during that explosive season could have been mighty impressive.

Scouts were again assembling and now had a new reason to bypass the Pacific Coast League star: his on-field temperament was called into question, due to the altercation with umpire Chadbourne. Even so, the St. Louis Browns were rumored to be considering Buzz as a pitcher and part-time outfielder. The Boston Red Sox were also in the bidding, salivating over the thought of the power-hitting outfielder patrolling Fenway Park.

The Oaks realized they’d better entertain any legitimate offers for their aging star. In addition to Buzz’s not getting any younger, his salary demands were increasing and reasons for not signing him were getting old. Another factor was the revised draft policy, greatly affecting the minor leagues. Initiated by the majors, big league clubs sought access to talented players at a reasonable cost; the new draft policy allowed minor league players to be “drafted” out of the minors and onto major league rosters.

Prior to actually being drafted, Arlett’s shot at the majors finally came late in 1930, when the Oaks sold his contract to the perennial last-place occupants of the National League: namely the Philadelphia Phillies. The configuration of Baker Bowl was thought to be perfect for the Arlett swing. The Buzzer was not strictly a pull hitter; he made smooth contact and was satisfied going with the pitch, to any field. Thanks to his great strength, it was not impossible to bang out opposite field dingers. Buzz planned to spend the off season working out, attempting to be in perfect condition for his major league debut.

Despite his regimen of getting into shape, Buzz started slow in spring training. The 32-year-old war-horse just had trouble getting into the big league routine. Although officially listed at 230 pounds at the start of the season, Arlett likely tipped the scales a few pounds over that figure. Indeed, everything about Buzz was big, even his bat. Ash was his material of choice, and he preferred to swing lumber weighing in at a staggering 44 ounces! He once placed an order that was rejected by the manufacturer; the supplier thought the 44-ounce designation was an error. Arlett personally weighed all new bats and felt only two out of any given dozen would be good. He had a favorite bat, lovingly referred to as “Big Bertha,” claiming this particular bat had more hits in her than any other. In the off season, he’d oil “Bertha” every two weeks to ensure she wouldn’t chip during the regular season.

Manager Burt Shotten was patient with the former PCL star and worked with Buzz in building his confidence, emphasizing the brilliant dozen years he’d contributed in the Coast League.

Toward the end of spring training, in Winter Haven, Buzz started to show signs of life at the plate. On the trip north, he caught fire and didn’t look back. When the season started on April 14, Buzz continued his fine stick work and the aging rookie became the most talked about player in all of baseball. Six weeks into the season, his numbers showed a league-leading .385 batting average, while placing second with 11 homers. For a while, it looked like he’d proven his worth as a major leaguer, until injuries took their toll.

How did comrades around the league take to the affable giant? In a May series, the Cubs invaded Philadelphia and decided to have some fun with the big rookie. The bench started to razz him about his physique and the number of years spent in the minor leagues, all spiced with salty language. Buzz marched over to the bench and started to remove his uniform shirt. The sight of big Buzz’s hairy chest and general invitation to “step out of the dugout and take a licking” had a calming effect on the Cub players. No one stepped forward, and subsequently the league became very careful in riding the big Californian.

By June, Arlett was thrilling fans with his exploits on the field. With Buzz hitting explosive home runs and creating excitement on the base paths, the small groups of fans at Baker Bowl at least had something to cheer. Buzz’s girth and shy demeanor made him appear surly to some fans. In reality, the gentle giant was friendly with press and public alike.

The injuries began in Cincinnati. Buzz hurt his leg while sliding and never quite regained his early-season form. In mid-June, he fractured his thumb in Philadelphia, trying to steal second base. At this point in the season, his average had fallen to .348, with Buzz stuck on 11 home runs. Buzz was out of the lineup for two weeks and when he returned, he couldn’t swing from the left side of the plate.

Arlett played some first base while recuperating, but his overall performance was just not the same. Buzz seemed to become indifferent and lackadaisical in spirit, further affecting his play. He probably sealed his fate on a hot August day, when he misplayed a routine fly to right. Pitcher Jumbo Jim Elliot was livid with the miscue and recommended an on-field rocking chair for the aging player. Buzz saw less playing time as the season progressed, spending most of his time in pinch hitting roles.

Buzz ultimately produced a .313 batting average, 18 homers and 72 RBI in his only big league season. His slugging percentage of .538 and was bested in the NL only by the likes of Chuck Klein, Rogers Hornsby, Chick Hafey, and Mel Ott. His fielding percentage, as a flychaser, was a low .955. Although the colorful giant was popular with Phillies fans — and the team improved to 6th place — some personnel changes had to be made for 1932.

Overall, the Phillies sought to improve the outfield by adding a speedy center fielder and moving Chuck Klein to right. The resulting move made Buzz expendable, and he was waived out of the league. He wanted to play back in the West once again; however, he was willing to come east if the money was right. In December of 1931, the Baltimore Orioles of the International League signed him. George Weiss, an astute baseball man, ran the Orioles and obviously saw value in bringing the big star to Baltimore.

Looking back at the 1931 season, Lefty O’Doul, a contemporary of Arlett in the Pacific Coast League, offered a sobering commentary on Buzz’s only season in the sun. He remarked to press that had Arlett been in the big leagues five years earlier, he would have been “the Babe Ruth of the National Circuit.”

The Orioles were a major league entry in the American League from 1901 until 1903, when the club was moved to New York. A new team settled into Baltimore and was embraced by the city. The International League Orioles became a powerhouse in the 1920s, winning 7 pennants during that decade. The team played at old Oriole Park, located on Greenmount Avenue in the city. Common to many parks of the era, it contained single tiered wooden construction. The park would be used until the 1940s when it was totally destroyed by fire, a calamity that eventually would lead to the Orioles playing at Memorial Stadium.

Fans and city alike took to their new slugger. “Buzzer,” as the Baltimore press affectionately called him, proceeded to put up impressive numbers for his new team. Early in the season, his powerful exploits caught the attention of awe struck fans. In a game on May 5 in Buffalo, Buzz hit for the cycle, securing 8 hits in 11 trips to the plate! In the 6th inning, Arlett reportedly hit a drive that sailed over the right field fence and through the window of a home where neighborhood ladies gathered for an afternoon of bridge. The unsuspecting homeowner was struck on the head by the towering drive! Another homer shot out of the stadium and through the front window of a house where a funeral was in progress. It’s said the deceased was a baseball fan and ultimately the ball stopped rolling at his casket.

On June 1, 1932, Buzz would enjoy a 4-homer day at Reading, Pennsylvania, hitting three from the left side and the last one right-handed, as the O’s posted a 14-13 victory.

This outstanding day at the plate would subsequently be followed by another explosive performance on July 4th. The big slugger proceeded to (once again) destroy the rival Reading Keys, with another 4-homer performance. In the first game of a doubleheader, Arlett hammered a grand slam from the right side of the plate, and then hit three more homers from the left side, as the Orioles defeated the Keys, 21-10!

As an encore, in his first at-bat of the second game, Arlett again cleared the fences, giving him five home runs in five consecutive at-bats. He later added a double, providing the offense leading to the Orioles sweep of the Keys; the second game tally was 9-8. The fans saw a hitting display that gave new meaning to 4th of July fireworks! Buzz Arlett appropriately added to his reputation as the Babe Ruth of the minor leagues.

Coincidentally, Buzz would appear on the diamond, with the legendary Babe, the very next day. On July 5 the New York Yankees would travel to Baltimore to challenge the O’s in an exhibition game. The O’s prevailed, defeating the Yanks, 9-2, with Buzz contributing a homer in the third inning. To give an idea of Buzz’s ample size, a photo appeared in the Baltimore Sun with Buzz standing between Lou Gehrig and Babe Ruth; Buzz is clearly the biggest of the three. Buzz wore a size 54 uniform; Babe Ruth wore a loose-fitting 52.

Arlett’s totals during the 1932 campaign included league-leading numbers in the following categories: home runs at 54; runs at 141 and runs batted in with 144; his batting average stood at .339. Incredible as it sounds, he hit 54 home runs despite missing almost a month of the season due to injuries. The 1932 season also marked a position switch for Buzz; previously a right fielder, he’d now patrol left field.

The Orioles finished second in the league during both the ’32 and ’33 campaigns. Buzz continued his tenure with the Orioles until the end of the 1933 season, posting a league-leading 39 home runs and contributing 135 runs scored, while hitting .343. That fall, the new business manager of the Orioles embarked on a youth movement that resulted in the wholesale elimination of players.

Arlett was traded to the Birmingham club of the Southern Association, prior to the start of the 1934 season. He played in 35 games for the Barons before the Minneapolis Millers of the American Association purchased his contract. The idea was to insert a strong bat into the lineup behind another power merchant named Joe Hauser.

Buzz entertained the Minneapolis fans on May 27, 1934, with his both his hitting and fielding. Buzz smacked a homer and two doubles to lead the club to victory over the Toledo Mud Hens at Nicollet Park. But it was a spectacular running, barehanded catch that produced several minutes of deafening cheers from the adoring crowd. The Minneapolis Tribune aptly noted that this was from a man whose fielding supposedly kept him out of the big leagues. In 1934, he ultimately led the loop with 41 homers, while contributing a .319 batting average.

The 1935 season got off to an inauspicious start when a spring training auto accident cost Buzz part of the ring finger on his left hand. In 122 games for the Millers, his home run production dropped to 25; however, his batting average was still a very respectable .360.

In 1936, Buzz divorced his first wife, Frances Arlett, whom he’d married in 1927. The couple separated in 1932, when Frances returned to California to live with her parents. The couple had no children, and Buzz listed desertion as cause for the split. Vivian Johnson became the second Mrs. Arlett. She was secretary to Millers owner Mike Kelly when they tied the knot.

Age and injuries caught up with Buzz in 1936, as he was relegated to part-time status with the Millers. His batting average fell to .316, with only 15 round-trippers.

His last appearance as a player was with the Syracuse Chiefs in 1937, going hitless in four plate appearances as a pinch hitter. He followed his playing career with managerial posts in the low minor leagues; he also did some scouting for the Yankees, Reds and Dodgers.

In retirement, Buzz purchased and operated a very successful restaurant and bar in Minneapolis. Arlett’s Place had some minor skirmishes with authorities in the early 1950s, due mostly to charges of illicit gambling on the premises.

The establishment naturally had its own baseball team, and Buzz was known to suit up as player into the early 1940s. Buzz participated in charity games, including a contest at Nicollet Park, pitting a makeshift all-star team against the Chicago Giants, a Negro League team.

In 1945, Buzz was inducted into the Pacific Coast League Hall of Fame, based on the outstanding career numbers he posted while playing for the Oakland Oaks. All told, during his minor league career, he hit a total of 432 home runs in 2,390 games, with a .341 lifetime batting average — all after starting as a pitcher.

In 1946, Oakland brought him back to honor their former star with a 10-day celebration on his behalf. Parties and gifts were in order, as Buzz was declared “the Mightiest Oak of All Time.” The event was planned by The Oakland Tribune and culminated at Emeryville Park on August 11. An estimated crowd of 6,000 was expected to attend, but true to form, the popular Arlett drew over 12,000 people. Buzz was presented with a brand new 1946 Ford; Arlett was so delighted with his automobile that he decided to forego the train and drive back home to Minneapolis. The thrifty Arlett kept the car over a dozen years and even drove it back to California to visit his brothers in 1958.

The fact that Buzz was so honored back in Oakland a full decade and a half after he originally left was not lost on the people of Minneapolis. The sentiment of an impressed populace was that “Buzz Arlett must’ve been quite a man to warrant such festivities.”

Arlett lived in the Minneapolis area until stricken with a heart attack in 1964; he passed away on May 16 at Northwestern Hospital. Buzz was 65 and was survived by his wife, a son, a daughter and his older brothers Harry and Dick.

Based on the exceptional numbers he produced during his great minor league career, he was named by the Society for American Baseball Research (SABR), in 1984, as the all-time greatest minor league player.

Epilogue

A few years ago, while gathering material about Buzz, I had occasion to correspond with an author named Tony Salin, who was also researching Arlett. We exchanged ideas and went back to our respective work. Subsequently, I learned of Tony’s untimely death and how his research material was left in the possession of The Baseball Reliquary, in California. I’m extremely grateful to Terry Cannon and the board members, for sharing Tony’s research. And to Tony, I’d just like to say thanks, and add “you did a Hall of Fame job in your research.”

Sources

Newspapers

Baltimore Sun

Chicago Tribune

Los Angeles Times

Minneapolis Times

Minneapolis Tribune

New York Times

New York World Telegram

Oakland Enquirer

Oakland Tribune

Philadelphia Inquirer

Sacramento Union

San Francisco Call and Post

San Francisco Examiner

The Sporting News

Washington Post

Other Sources

Bready, James H. Baseball in Baltimore. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, 1998.

Lavoie, Steven. Northern California Baseball History. Cleveland: SABR, 1998.

McEligot, Warren J. “Martyrs of the Baseball Diamond.” Baseball Magazine, June 1934.

Reichler, Joseph L. The Baseball Encyclopedia. New York: Macmillan, 1982.

Selko, Jamie. “Single Season Wonders.” Baseball Research Journal, 1990.

Snelling, Dennis. The PCL: A Statistical History, 1903-1957. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 1995.

Tholkes, Robert. Toledo Toppled By Buzz Saw in 1934. Baseball Research Journal, 1982.

Thornley, Stew. On to Nicollet. Minneapolis: Nodin Press, 2000.

Tomlinson, Gerald. “A Minor League Legend: Buzz Arlett, ‘The “Mightiest Oak’.” Baseball Research Journal, 1988.

Zingg, Paul J., and Mark D. Medeiros. Runs, Hits, and an Era, the PCL 1903-58, Champaign, Illinois: Illini Books, 1994.

Full Name

Russell Loris Arlett

Born

January 3, 1899 at Elmhurst, CA (USA)

Died

May 16, 1964 at Minneapolis, MN (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.