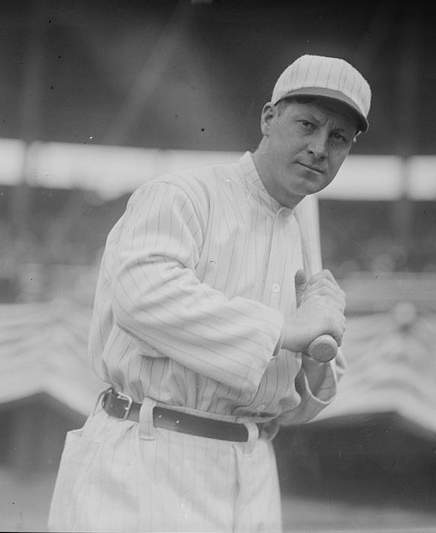

Benny Kauff

A flashy dresser and world-class trash talker, Benny Kauff was the Deion Sanders of the Deadball Era. “I’ll make them all forget that a guy named Ty Cobb ever pulled on a baseball shoe,” the brash 26-year-old told reporters on his arrival with the New York Giants in 1916. Kauff’s boastfulness was not without some justification. Dubbed “The Ty Cobb of the Federal League,” Kauff was the most heralded young player of his generation, a five-tool star whose unique combination of speed and power defied his stocky 5’8″ frame. Though he performed well in the National League’s faster company, Kauff never did match the high expectations he and others had set for him, and his career ended prematurely in 1921 with his controversial banishment from the game.

A flashy dresser and world-class trash talker, Benny Kauff was the Deion Sanders of the Deadball Era. “I’ll make them all forget that a guy named Ty Cobb ever pulled on a baseball shoe,” the brash 26-year-old told reporters on his arrival with the New York Giants in 1916. Kauff’s boastfulness was not without some justification. Dubbed “The Ty Cobb of the Federal League,” Kauff was the most heralded young player of his generation, a five-tool star whose unique combination of speed and power defied his stocky 5’8″ frame. Though he performed well in the National League’s faster company, Kauff never did match the high expectations he and others had set for him, and his career ended prematurely in 1921 with his controversial banishment from the game.

Benjamin Michael Kauff was born on January 5, 1890, in Pomeroy, Ohio, the oldest child of William and Hanna Kauff. The Kauffs were descended from German immigrants, and because of his name many sources incorrectly describe him as a Jew. William Kauff worked independently in the mines, and when Benny turned 11 he quit school and went into partnership with his father. Kauff was unusually strong, “a miniature Samson” in the words of one reporter. “Benny’s shoulders and arms are out of proportion to his height,” the scribe continued. “Despite this fact, he is not muscle-bound; can throw a ball like a shot out of a rifle, and is as fast and agile as a rabbit.” Benny credited his strength to his long hours in the mines. “The work was very hard,” he told Baseball Magazine. “Seven years I worked in the dust and grime and baseball proved my way of escape from a lifetime spent in the same monotonous way.”

Kauff got his start playing weekend baseball for local amateur teams. By 1909 he was a jack-of-all-trades for the Keystones, a neighborhood club. “In my first game I caught for three innings, pitched for three innings, and then caught for three more innings,” Kauff recalled. His pitching was good enough to merit a professional gig with the Parkersburg, West Virginia, club of the Virginia Valley League in 1910. The league didn’t keep official statistics, but sources attest that Kauff compiled a 14-4 pitching record with a .417 batting average and 87 stolen bases. Those numbers would make any scout salivate, but, curiously, more than one major league club passed up an opportunity to land him.

The New York Highlanders invited Kauff to spring training in 1911. Noting the lefthander’s rifle arm and brilliance with the bat, manager Hal Chase projected him as an outfielder. But he also decided Kauff was too green for the majors and sent him down to Bridgeport of the Connecticut State League, where Kauff established himself as one of the league’s most promising young players. The Highlanders looked him over again in 1912, then farmed him out after he appeared in all of five games. This time he wound up with Hartford, where he led the Eastern Association with a .345 batting average in 1913. That performance caught the attention of the St. Louis Cardinals, who planted Kauff with Indianapolis of the American Association, hoping they could hide him there until they needed his services.

Kauff did play for Indianapolis in 1914, but not in the American Association. Prior to the start of the season, the Hoosiers of the upstart Federal League swooped in and offered him double his previous salary. Understandably frustrated with his lack of progress in the established leagues, Kauff accepted and quickly became the league’s top attraction. Playing primarily in center field, he easily paced the circuit in runs (120), hits (211), on-base percentage (.447), and stolen bases (75), and his .370 batting average topped his nearest competitor by more than 20 points.

As Kauff lifted the Hoosiers to the pennant, the press notices started piling up. “Kauff is the premier slugger, premier fielder, premier base stealer and best all-round player in the league,” Sporting Life gushed. “He is being called a second Ty Cobb, yet there are many followers of the Federal clubs who say that within next season Kauff will play rings around the Georgia Peach.” According to sportswriter Frank Graham, Kauff loved the publicity “and cheerfully agreed that he was at least Ty’s equal, if not his superior, for he was not bound by false modesty.”

Off the field, Kauff possessed a wardrobe, replete with diamond rings and fancy diamond tiepins, to match his ego. “Having seen him in civilian array, we are undecided whether Benny Kauff is a better show on or off,” Damon Runyan remarked. “In his working apparel he is a companion piece to Tyrus Raymond Cobb and Tris Speaker, while in his street make-up he is a sort of Diamond Jim Brady reduced to a baseball salary size.” Yet Kauff wasn’t a snob. To his teammates he was renowned for his ability to chew tobacco, smoke a cigar, and drink a glass of beer all at the same time, “without interruption to any of the three pursuits.”

In short, Kauff was a hell of a lot of fun, and the New York Giants wanted him. After the 1914 season, the Federal League’s Indianapolis franchise shifted to Newark, but Kauff found himself transferred to the Brooklyn Tip Tops as repayment of the outgoing Indianapolis owner’s old debts. Kauff thought he should have been a free agent, so he negotiated a three-year contract with the Giants in April 1915. At the press conference announcing his signing, Kauff declared that he would “bunt a home run into that right field stand every day.” But when the Giants attempted to take the field against the Boston Braves with Kauff in center field later that afternoon, the Braves refused to play, arguing that Kauff was ineligible because he had signed with an outlaw league. NL President John Tener agreed and voided the contract.

Exiled to Brooklyn, Kauff again played brilliantly, leading the Federal League with a .342 batting average, .446 on-base percentage, and .509 slugging percentage, all while swiping a league-best 55 bases. That performance did nothing to dissuade the Giants from their quest to land the star. When the Federal League folded following the 1915 season, Kauff applied for and received reinstatement into organized baseball, then inked another contract with the Giants. It was, Kauff confided to a reporter, “the ambition of my life.”

A half-century later, Graham still vividly recalled Kauff’s first appearance in camp with the Giants in the spring of 1916: “He wore a loudly-striped silk shirt, an expensive blue suit, patent leather shoes, a fur-collared overcoat and a derby hat,” Graham wrote. “He was adorned with a huge diamond stickpin, an equally huge diamond ring and a gold watch encrusted with diamonds, and he had roughly $7,500 in his pockets.” The forgiving right-field porch of the Polo Grounds was still on Kauff’s mind. “I’ll hit so many balls into the grandstand that the management will have to put screens up in front to protect the fans and save the money that lost balls would cost,” he bragged. The New York press loved his act, and soon headlines like “All Pitchers Will Be Easy, Kauff Admits” graced the sports pages of the major dailies.

Judged against the hype, Kauff was a huge disappointment in his first year in New York. Playing center field every day, Kauff didn’t set the league on fire, he didn’t destroy NL pitching, he didn’t reinvent the game; he was merely very good. His unimpressive .264 batting average masked other attributes: a knack for getting on base, a penchant for the long ball (he hit nine home runs and 15 triples that season), and an aggressive—though some called it reckless—baserunning style that produced 40 stolen bases. That package would have been a credit to any team, but alas, it didn’t measure up to Ty Cobb. The fans never let him forget it. “Why, do you know, back in New York they jeer me if I don’t knock the cover off the ball with every swing,” Kauff groused to reporters during a June road trip. He also complained that he’d been unfairly caricatured by the media. “The newspaper men in New York are inclined to josh a fellow a little more than seems necessary,” he said. “I have tried to treat everybody fairly. And while there is probably no ill feeling on their part, they have made me out a sort of swell headed gink.”

In the eyes of a public fixated on batting averages, Kauff played much better in 1917 and 1918, as he cleared the magic .300 barrier each season. But with more singles came fewer walks and extra-base hits, and as a result his cumulative offensive value remained more or less constant. He managed to steal some headlines in the 1917 World’s Series when his two home runs propelled New York to a Game Four victory. He was in the middle of another fine season in 1918 when he was drafted into the Army, helping train new recruits until the Great War ended that November. In retrospect, Kauff’s wartime break from baseball was an important demarcation in his brief career. In his first 2½ seasons in the NL, Kauff found himself at the center of a swirling vortex of media hype and criticism, mostly of his own creation. Yet when he returned to the Polo Grounds in 1919, the prevailing atmosphere was far more somber—and scandalous.

Kauff put forth another good season in 1919, finishing second in the NL in home runs with 10 and fourth in RBI with 67. But despite Kauff’s efforts, and despite having the league’s best offense, the Giants never seriously challenged for the pennant, finishing a disappointing nine games out of first place. By September New York’s hopeless situation convinced at least two regulars, Hal Chase and Heinie Zimmerman, to start fixing games. During one western road trip, Chase and Zimmerman tried to bribe several teammates to help them, including Kauff, who reported the attempt to manager John McGraw. Despite that act of integrity, rumors of Kauff’s own dishonesty soon began to surface. Billy Maharg, one of the conspirators who helped fix the 1919 World’s Series, later claimed that Kauff had taken part in that scheme, and Arnold Rothstein, the notorious gambler who bankrolled the operation, reportedly told American League president Ban Johnson that Kauff had asked him for $50,000 in bribe money to give to the players prior to the Series.

But the most substantive allegation of wrongdoing emerged in February 1920 when Kauff was indicted on auto-theft charges in connection with the Manhattan automobile accessory business he had started the previous fall with his half-brother, Frank Home, and Giants teammate Jesse Barnes. In the complaint, authorities alleged that in December Kauff and two associates stole a vehicle from a West End Avenue parking lot, then fitted it with a new paint job, new tires, and a new license before selling it to an unsuspecting customer for $1,800. Kauff denied the charges, contending that he was unaware the car was stolen when he re-sold it.

That’s where matters stood when the bell rung on the 1920 season. Despite the ongoing criminal investigation, Kauff reported for duty with the Giants. But with the ugly rumors surrounding Kauff and the entire sport that season, McGraw grew reluctant to play his talented center fielder and finally traded him to the Toronto Maple Leafs of the International League in early July. In the half-season he spent in Toronto, Kauff batted .343 and stole 28 bases, even as he endured taunts from fans. The auto-theft case still had not gone to trial, but at season’s end McGraw reacquired Kauff anyway, telling reporters he expected to use him as his regular center fielder the following season. “Kauff is innocent of the charge of buying stolen automobiles,” McGraw contended. “He simply got in with evil companions who mixed him into the case before he knew it.”

Commissioner Landis, however, had his own suspicions. After meeting with Kauff prior to the start of the 1921 season, Landis ruled that the Giant center fielder would be ineligible pending resolution of the criminal matter. The trial finally began in early May and lasted five days. The state’s chief witnesses were Kauff’s two associates, both ex-cons, who claimed they helped Kauff select and refit the stolen automobile. The defense countered that Kauff had been eating dinner with his wife at the time of the alleged incident, then brought out a series of character witnesses, including McGraw and teammate George Burns, to defend Kauff’s reputation. The jury deliberated for less than an hour before returning with a not-guilty verdict.

After his victory in court, Kauff had every expectation that he would be quickly reinstated into the good graces of organized baseball. He was in for a surprise. A former federal judge famous for handing down cavalier judgments, Landis sat on Kauff’s application for much of the summer, then refused to lift the ban. Despite the verdict, Landis insisted that the trial “disclosed a state of affairs that more than seriously compromises your character and reputation. The reasonable and necessary result of this is that your mere presence in the lineup would inevitably burden patrons of the game with grave apprehension as to its integrity.” Landis later told Fred Lieb that the jury’s verdict “smelled to high heaven” and was “one of the worst miscarriages of justice that ever came under my observation.”

Kauff had never been formally accused of throwing games, but The Sporting News applauded Landis’ decision and linked Kauff with the eight banned Black Sox players. “They, too, like Kauff, are ‘innocent’ in the eyes of a trial court, but the court of public opinion has its own notions regarding them,” the paper editorialized. “Presumably we have heard the last of Benny Kauff in baseball. It is well.”

Stunned by Landis’ decision, Kauff applied to the New York State Supreme Court for a permanent injunction against his banishment. “I say that I am every inch as much of a gentleman, and have as high a sense of ethics and character as this man Landis, who has no standing as far as I am concerned,” Kauff said. But all hope for resuscitating his career ended in January 1922 when the court concluded it had no grounds to act on Kauff’s request, though in his ruling Justice E. G. Whitaker agreed that “an apparent injustice has been done the plaintiff [Kauff].”

His playing career over, Kauff lived out much of the rest of his life in Columbus, Ohio, with his wife, Hazel, and the couple’s only child, Robert. According to his obituary, the banned player worked for 22 years as a scout, and later, appropriately enough, as a clothing salesman. Kauff died on November 17, 1961, after suffering a cerebral hemorrhage. He is buried in Columbus’ Union Cemetery.

Author’s note

A slightly different version of this biography appeared in Tom Simon, ed., Deadball Stars of the National League (Washington, D.C.: Brassey’s, Inc., 2004).

Sources

For this biography, the author used a number of contemporary sources, especially those found in the subject’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

Full Name

Benjamin Michael Kauff

Born

January 5, 1890 at Pomeroy, OH (USA)

Died

November 17, 1961 at Columbus, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.