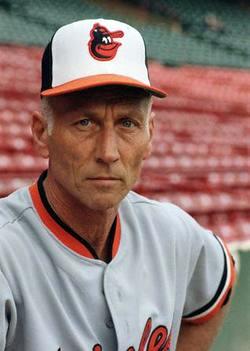

Cal Ripken Sr.

Cal Ripken Sr. spent 36 years in the Baltimore Orioles organization as a player, manager, coach, scout, and minor league instructor. Hundreds of Oriole prospects benefited under the tutelage of the man who once said, “Don’t just practice. Practice right, and you’ll do things right in the game. Practice doesn’t make perfect. Perfect practice makes perfect.” 1 During his time in baseball, Ripken epitomized what was known as the “Oriole Way.” Implementation of the fundamentals of the game, hard work, and being accountable for your actions on-and-off the field are the cornerstones of this time-honored tradition. During the early 1960s, coaches at every level of the Baltimore farm system instructed their young players in these basic principles of the game. This consistent philosophy of stressing fundamentals made it easier for Oriole prospects to adjust as they advanced through the minor leagues.

Cal Ripken Sr. spent 36 years in the Baltimore Orioles organization as a player, manager, coach, scout, and minor league instructor. Hundreds of Oriole prospects benefited under the tutelage of the man who once said, “Don’t just practice. Practice right, and you’ll do things right in the game. Practice doesn’t make perfect. Perfect practice makes perfect.” 1 During his time in baseball, Ripken epitomized what was known as the “Oriole Way.” Implementation of the fundamentals of the game, hard work, and being accountable for your actions on-and-off the field are the cornerstones of this time-honored tradition. During the early 1960s, coaches at every level of the Baltimore farm system instructed their young players in these basic principles of the game. This consistent philosophy of stressing fundamentals made it easier for Oriole prospects to adjust as they advanced through the minor leagues.

Former Oriole pitching coach Ray Miller told the Associated Press, “We always talk about the Oriole Way. Cal Ripken Sr. was the one who indoctrinated each one of us who came in.”2

Detroit Tigers manager Jim Leyland wrote in the forward of Coaching Youth Baseball the Ripken Way, “I had the good fortune to manage against Cal Ripken back in 1974 in the Southern League. To this day, I believe he was one of the best fundamental baseball teachers I have ever been around.” 3

A dedicated family man and father of four, Cal Ripken Sr. saw two of his sons, Cal Jr. and Billy, influenced by his love of the game, choose baseball as their profession. The former went on to an iconic Hall of Fame career; the latter became a solid major league player.

Calvin Edwin “Cal” Ripken was born on December 17, 1935, in a small room located above his grandparents’ (Frederick and Affena Ripken) general store in Stepney, Maryland. Calvin was the youngest of three boys born to Arend and Clara (Oliver) Ripken. Calvin’s father’s descendants were from Germany, and his mother’s ancestors hailed from the Emerald Isle.

Calvin’s father Arend was the first baseball enthusiast in the family, occasionally playing in local pickup games on the weekends. Later, Arend’s sons, Ollie, Bill and Cal, became star players for the Aberdeen Canners in the semiprofessional Susquehanna League.

Tragedy struck the Ripken family on December 12, 1944, when Arend was killed in a car accident. Persevering through the loss of a parent, Cal’s older brothers took on an even more influential role in their younger sibling’s life. Ripken got his start on the diamond as the batboy for the Canners in 1946. Baseball-savvy Aberdeen manager Fred Baldwin, fearing opponents were stealing his signs, started sending the signals to ten-year-old Cal who, in turn, relayed them to the players. Baldwin later recounted that he figured the opposing clubs would never suspect that the batboy was actually giving the signs. Cal Ripken eventually became the starting catcher for the Canners in 1953, batting .314 and earning an honorable mention to the Susquehanna League’s All-Star squad.

Ripken went on to become a star catcher on the Aberdeen High baseball team and a standout performer on the school’s soccer squad. As a senior, Cal received a scholarship offer from Washington and Lee College but turned it down in order to pursue a career in professional baseball.

After graduating from high school in 1953, the 6’1” 175-pound catcher continued to play ball in the Susquehanna League (a weekend amateur league in which players received a few dollars on the side) with the Havre De Grace Cokers, hitting .380 in 1956. 4 Ripken’s outstanding play did not go unnoticed by the local ivory hunters. Near the end of the 1956 season, scout John “Poke” Whelan signed the young catcher to a minor-league contract with the Baltimore Orioles.

Ripken broke into pro ball in 1957, hitting .289 with the Phoenix Stars in the Class C Arizona-Mexico League. During that time he was earning $150 a-month salary while living on three-dollars-a-day meal money. When Ripken returned home after the season, he married his high school sweetheart, the former Violet Gross on November 30, 1957.

Ripken was promoted to the Wilson Tobs in the Class B Carolina League in 1958. That season, he led all catchers with a .996 fielding percentage and 60 assists. While a member of the Tobs, Ripken caught Steve Dawlkowski, arguably the hardest throwing pitcher ever to play in the Baltimore organization. Dawlkowski threw the ball with such velocity that one of his errant tosses tore the ear lobe off an opposing batter. Another time one of Dawlkowski’s heaves struck the umpire in the face mask and knocked him unconscious. Years later Ripken was asked to compare perennial fireballer Nolan Ryan to Dawlkowski, “Steve was faster, I don’t even have to think about it. Nolan, though, had other pitches and could get them over the plate.” 5

The Orioles sent Ripken to the Pensacola Dons in the Class D Alabama-Florida League in May of 1959 to replace catcher Bill Massey, who was sidelined with a broken hand. The Dons batted Ripken second in the lineup, and he responded with a .292 batting average, earning him a selection to the All-Star team. Ripken was transferred to Amarillo in the Class AA Texas League late in the season.

In 1960, Ripken was sent to the Fox Cities Foxes (Appleton, Wisconsin) in the Class B Northern League, where he hit .281 with 74 RBIs. Defensively, he played the outfield and catcher, posting a .990 and .972 fielding percentage at each position. In addition to his ball playing duties, Cal Sr. drove the team bus for most of the year after manager Earl Weaver fired the driver. During his days as a player, Ripken caught a number of pitchers who were destined for the majors. One of these future stars included 1964 American League Cy Young Award winner Dean Chance, who went 12-9 for Fox Cities that year.

Ripken started off spring training in 1961 with the Oriole Triple A affiliate, the Rochester Red Wings. Early in camp, he was struck on the right shoulder by consecutive foul tips during a spring training game in Daytona. Ripken was able to finish the game, throwing out two potential base stealers. The following day, his shoulder was so sore he could barely pick up a baseball. His arm would eventually come around to a limited degree, but it took Ripken nearly six years to fully recover from the injury.

A few weeks into camp, Ripken pulled off a rare feat while catching in an inter-squad game. Orioles first base coach George Staller was managing one of the teams and was aware of Ripken’s arm injury. The first eight men who got on base were given the steal sign by Staller. Ripken later spoke about what happened next in The Sporting News,”I threw all eight of them out. I couldn’t throw the ball hard but I got rid of it quick.” 6

Still feeling the effects from the shoulder injury, Cal was sent to Little Rock in the Southern Association early in the 1961 season. In June, Orioles farm director Harry Dalton contacted him to see if he would be interested in taking over as player-manager of the Leesburg team in the Class D Florida State League. Leesburg’s manager Billy DeMars had recently been promoted up the Orioles minor league chain to Tri Cities in the Class B Northwest League, and the organization needed a good baseball man to fill the vacancy. Ripken accepted the offer and began his managerial career.

The following year the Leesburg team folded, and Ripken returned to Appleton to manage the Fox Cities Foxes, who had recently switched over to the Class D Midwest League. The owner of the bus company in Appleton, Ollie Lindquist, refused to lease the bus to the team unless Cal agreed to be the driver. Ripken caught the first thirty games of the season, but his playing time dropped off when the Orioles’ front office transferred catcher Bill Shirah to the team. In what would be his last year as an active player, Ripken was named Manager of the Year as the Foxes finished one full game out of first place in the second half of the split season.

Cal stayed on with Fox Cities in 1963, and the Midwest League was bumped up to Class A status. The next season, Ripken moved on to the Aberdeen (South Dakota) Pheasants of the Class A Northern League, where he finished second in the standings again. The following year everything fell into place for the Pheasants as they ran away with the pennant, finishing twelve games up on the second place club. Aberdeen went on to capture the league playoffs and Cal was named Manager of the Year for his outstanding on-field accomplishments. Nine of the Aberdeen players–Jim Palmer, Lou Pinella, Andy Etchebarren, Eddie Watt, Mark Belanger, Tom Fisher, Mike Davison, Dave Leonhard, and Mike Fiore–would eventually make it to the majors.

The following off-season, the Orioles management transferred Ripken from Aberdeen to the Tri-Cities Atoms to replace manager Mike Heath, who had been on a three-year loan from the Los Angeles Angels. The president of the Aberdeen Pheasants, Les Keller, spoke to the Tri-City Herald about losing his team’s skipper, “Ripken is an outstanding baseball manager. He is respected by his players and is truly a fine leader. But most of all he is a gentleman whose personality and character made him a most welcome member of our community.” 7

Ripken’s winning ways immediately rubbed off on his new team as the Atoms captured the Class A Northwest League championship in 1965. The loop played a spilt schedule that year, and the Atoms finished in first place in the second half of the season. Ripken’s charges stayed hot through the playoffs, sweeping the Lewiston Broncs, winners of the second half, in three games. Sportswriters and broadcasters from every team in the league voted Ripken and four of his players, Bobby Floyd, Mike Fiore, Dave May and Herm Rathman to the circuit’s All-Star team.

Ripken went on to make managerial stops at Miami, Elmira, Rochester, Dallas-Fort Worth, and Ashville, where he won another minor-league championship in 1972. During that time, he managed the Orioles team in the Florida Instructional League. In 1968, Cal Sr. managed Jim Palmer at Elmira and in the Instructional League when the future Hall of Fame pitcher was battling serious shoulder problems. Thanks to Ripken and Orioles pitching coach George Bamberger’s advice and guidance during his rehab, Palmer was able to recover from the injury. Years later, Cal Sr. influenced another Oriole Hall of Famer’s career when he convinced the Baltimore front office to allow first baseman Eddie Murray to become a switch-hitter.

Ripken in January 1975 became an Oriole scout and consultant on free agent signings as well as an overall troubleshooter for Baltimore’s entire minor league system. The following season, he was named the Orioles bullpen coach, replacing George Staller who had recently retired. On June 27, 1977, he took over as the Orioles third base coach after Billy Hunter resigned from the position to take the manager’s job with the Texas Rangers.

In June of 1979, Ripken and pitching coach Ray Miller noticed a flaw in Steve Stone’s pitching delivery. Stone, who hadn’t been extending his arm properly, pitched five innings of no-hit ball in his next outing after making the adjustments suggested by the two coaches. The following year, Stone won the American League Cy Young Award.

During his tenure as an Orioles coach, Ripken filled in as manager whenever skipper Earl Weaver was ejected from the game. He was also the head of a five-man coaches committee who took over for Weaver when the Earl of Baltimore was suspended in late August of 1979 for questioning umpire Ron Luciano’s integrity.

Earl Weaver left the Baltimore Orioles after the 1982 season, and many people within the organization felt that Cal Ripken Sr. would be named as manager. Surprisingly, Orioles GM Hank Peters skipped over Ripken in favor of New York Yankees coach Joe Altobelli. Pitcher Jim Palmer spoke to the Associated Press about the power struggle between Hank Peters and Weaver as the reason for Ripken being passed over. “That’s why Ripken’s not the manager. Peters wanted all the remnants of Weaver out. The kiss of death for Ripken was when Earl said Cal should be manager–especially when Earl said if Cal had any problems he could just call him.” 8

Ripken continued on as the club’s third base coach. In 1983, he finally enjoyed a World Series title after coming out on the losing end in 1979. In 1987, Ripken was hired to manage the Baltimore Orioles. When Billy Ripken was called up to the bigs in July, Cal Sr. became the first major league manager to have two sons playing on his team. When asked by the Associated Press about the unique situation, Senior replied, “ We just happen to be in the same business at the same time. Maybe years from now, when I’m reflecting upon things in my rocking chair I’ll smile about all this, but for now they’re just a second baseman and shortstop on my ballclub.” 9

Although the team was clearly in the rebuilding stages, Ripken was relieved of his managerial duties by GM Roland Hemond after losing the first six games of the 1988 season. Hemond spoke to the press about firing Ripken. “It, six games, is certainly a short span and I feel some degree of compassion and guilt for Cal. But there is a lot at stake….. I just don’t see the positive signs of improvement I wanted to see.”10

Years later Ripken spoke about his firing in the Baltimore Sun: “Edward Bennett Williams, the owner then, decided he was going to roll over my contract for 1988 and said he wanted me to have the chance to manage a decent club, so it was agreed to be a rebuilding year. We had many meetings based on trying to educate people to do the right things. I kept telling them we were signing too many soft-tossing pitchers. The fastball is baseball’s best pitch. Always has been, always will be.” 11

Frank Robinson replaced Ripken as the Orioles manager and the Hall of Fame outfielder went on to lose a record-setting fifteen more games in a row. Cal returned to the Orioles as the third base coach and training camp coordinator the following year.

In 1991, Johnny Oates was hired to manage the Orioles. Shortly after his arrival, Ripken gave Oates a stack of notebooks with information that he’d compiled during his three decades in baseball. “I think everyone knows that’s a special family to me,” Oates said. “Cal Sr. was my first manager in professional ball, and I don’t think there was anyone who knew more about the game. Those notebooks weren’t just how to run a team. They were how to run an organization. His emphasis was that there are reasons for doing certain things. There’s a reason you do some things on the first day and others on the third day. And the biggest thing was letting the team know you’ve got a plan. He said you can’t go out the first day and start stammering.” 12

Ripken remained as third base coach for the Orioles until he was relieved of his duties on October 15, 1992. The man who persuaded the Orioles to let Eddie Murray switch-hit, helped Jim Palmer overcome arm problems, and taught the fundamentals of the game to scores of future major leaguers was told he was no longer needed on the team.

That day, he was called to a meeting that included general manager Roland Hemond, assistant general manager Frank Robinson and manager Johnny Oates. “Roland told me we have to move some people along [ostensibly to open opportunities for younger coaches],” Ripken said. “He said he wanted me to coordinate the minor-league camp and also I’d probably spend some time with the major-league club. I listened and asked him, ‘Before you go flowering up that job, tell me why I’m not staying here.’ He said again because ‘we have to move some people along.’ I asked him when he wanted an answer. He mentioned three or four days. I thought it out, reviewed it and called back and told him I couldn’t accept the proposal. They announced I retired, I didn’t retire.” 13

Ripken also addressed some anonymous sources who had intimated that the Orioles third base coach had made himself unapproachable to the players. “That’s wrong, the players never stopped coming to me asking for help. The biggest laugh I got was when I read in some newspaper that I sat in the back row of the bus to get away from everybody. Know why I sat there? So I could smoke cigarettes.” 14

A play that occurred on September 22, 1992, at Camden Yards against Toronto that may have contributed to Ripken’s demise as the Birds’ third base coach. With one out in the ninth inning Mark McLemore hit a fly ball to medium center field, and Ripken held Tim Hulett, who was the possible tying run, at third base. The next batter, Mike Devereaux, flied out, and the Orioles lost the game 4-3. Cal defended his decision not to send Hulett on McLemore’s fly ball: “I can’t believe that had anything to do with [my firing]. If you have any understanding of how baseball is played, you realize a coach never wants a tying run thrown out at home plate. The ball wasn’t hit that deep, and Tim Hulett is not a good runner. We had Mike Devereaux at the plate, and we have a chance to tie or even win the game. You don’t take a high-risk chance at that point.” 15

Asked about leaving the Orioles, Ripken replied, “I wasn’t happy about being fired. But you have to abide by the decision. The sun came up the next day. And it’s come up every day since then. There are two things I always say you have to do in baseball, and that’s adjust and readjust. You have to do the same thing in life. You have to accept things for what they are. I don’t worry about the water under that dam over here because I can’t do anything about it, and I don’t worry about crossing that bridge over there because I haven’t gotten to it yet.”

During his retirement years, Cal Sr. was rarely seen at Oriole Park at Camden Yards. However, for two days, September 5-6, 1995, the entire Ripken family came to the ballpark to watch Cal Jr. tie and eventually break Lou Gehrig’s consecutive games played record. Ripken Sr. later spoke humbly about his son’s amazing achievement. “Cal has given me a lot of credit for a lot of things. I don’t deserve that credit. He deserves it. He’s the one who went out and did these things.” 16

In 1996, Cal Ripken Sr. was inducted into the Baltimore Orioles Hall of Fame along with Billy Hunter and Jerry Hoffberger. In a testament to their popularity, over 400 people attended the pre-induction luncheon at the Sheraton Inner Harbor Hotel in Baltimore. In the years that followed, Cal Sr. and his wife Vi stayed in touch with the game by driving to Florida to watch the Orioles work out during spring training. At home, Ripken kept active by playing golf and horseshoes. He continued to operate his baseball clinics as well as his Cal Ripken Baseball School at Mt. St. Mary’s in Emmitsburg, Maryland. He also remained heavily involved with the Maryland Special Olympics.

Sadly, on March 25, 1999, Cal Ripken Sr. passed away at the Johns Hopkins Oncology Center after a long bout with lung cancer. He was survived by his wife Vi and their four children (Ellen, Cal, Fred, and Billy) along with six grandchildren. Cal Sr. was interred at Baker Cemetery in Aberdeen, Maryland.

In 2001, members of the Ripken family started the philanthropic Cal Ripken Sr. Foundation in his honor. The groups mission statement is: “Cal Ripken Sr. Foundation helps build character and teach critical life lessons to disadvantaged young people living in America’s most distressed communities through baseball and softball themed programs.”

In 2004, Cal Ripken Sr. was inducted into the Appleton (Wisconsin) Baseball Hall of Fame for his accomplishments with the Fox Cities Team.

In addition, the museum located on the club level of Ripken Stadium in Aberdeen has a display of Cal Sr.’s catching gear along with other memorabilia from his playing career.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the following people who assisted me with this biography:

Bill Haelig for generously sharing his vast knowledge of the Ripken’s baseball history as well as the written account of his oral presentation on the three Ripken brothers from the 2009 SABR convention. Bill provided me with the information on Cal Ripken Sr.’s amateur baseball career.

Jim Lindsey, Director of Media, Aberdeen Room Archives and Museum.

The librarians at the Paul Smith Library in New Freedom, Pennsylvania, for kindly assisting me in acquiring source material through Inter-library loan.

Sources

Armour, Mark. “Jim Palmer.” SABR Baseball Biography Project.

http://www.baseball-reference.com

Klingaman, Mike. “Ripken’s Roots Run Deep In Maryland With Hundreds Of Relatives.” Baltimore Sun. September 4, 1995.

Ray, David. Diamond Gems: Life Lessons Between the Lines. Maitland. Florida: Xulon Press, 2008.

http://www.ripkenbaseball.com

Ripken Jr., Cal, with Billy Ripken and Scott Lowe. Coaching Youth Baseball the Ripken Way. Champaign, Illinois: Human Kinetics, 2007.

Ripken Sr., Cal, with Larry Burke, The Ripken Way: A Manuel for Baseball and Life. New York: Pocket Books, 1999.

Wikipedia.com

Baltimore Sun

Daily (Kansas) Union

Eugene (Oregon) Register Guard

Pittsburgh Press

Schenectady Gazette

Toledo Blade

The (Washington) Spokesman-Review

The Sporting News

Notes

1 Mark Muske “Ex-Manager Cal Ripken Sr. Dies,” Washington Post, March 26, 1999, D1

2 “Cal Ripken Sr. Dead at 63,” Associated Press Quote excerpted from the Nevada Daily Mail March 28, 1999. 109

3 Cal Ripken Jr. Cal with Billy Ripken and Scott Lowe, Coaching Youth Baseball the Ripken Way.(Champaign, Illinois, 2007, Human Kinetics), vi.

4 Baltimore Sun, January 9, 1957: S15. This article noted that Ripken hit .380 in the Susquehanna League but did not list his team. Additional information provided by a questionnaire from William J. Weiss (San Mateo, CA) sent to Cal Ripken date stamped 02/23/57 “Clubs With Whom You Played Before Entering Organized Baseball.” Cal Sr. wrote back, the Aberdeen Canners and Havre De Grace Cokers. (From Bill Haelig’s Ripken Collection).

5 John Steadman “Cal Ripken Sr. Cool After Winter Of His Discontent,” Baltimore Sun, March 7, 1993, 1D

6 Doug Brown, “Up Up Goes Ripken On The Pilot Ladder,” The Sporting News December 28, 1968, 32

7 Tri-City Herald, February 16,1965.

8“Palmer Charges Oriole Politics,” Associated Press, Quote excerpted from the Reading Eagle, November 18, 1982, 93

9 David Ginsberg, Associated Press, Quote excerpted from the Daily Union March 26, 1999,13

10 Bob O’Donnell, “Grounded Orioles fire Ripken, hire Robinson To Get Them Airborne Again,” Fort Worth Star Telegram. Quote excerpted from the Deseret News April 13,1988, 18

11 John Steadman, “Cal Ripken Sr. Cool After Winter Of His Discontent,” Baltimore Sun, March 7, 1993, 1D

12 Richard Justice, “Oriole Notebook: Oates recalls mentor Ripken,” Washington Post May 19, 2000, D6

13 John Steadman, “Cal Ripken Sr. Cool After Winter Of His Discontent,” Baltimore Sun, March 7, 1993, 1D.

14 Ibid.

15 Ibid.

16 Mark Muske, “Ex-Manager Cal Ripken Sr.Dies,” Washington Post, March 26, 1999.D1

Full Name

Calvin Edwin Ripken

Born

December 17, 1935 at Aberdeen, MD (USA)

Died

March 25, 1999 at Baltimore, MD (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.