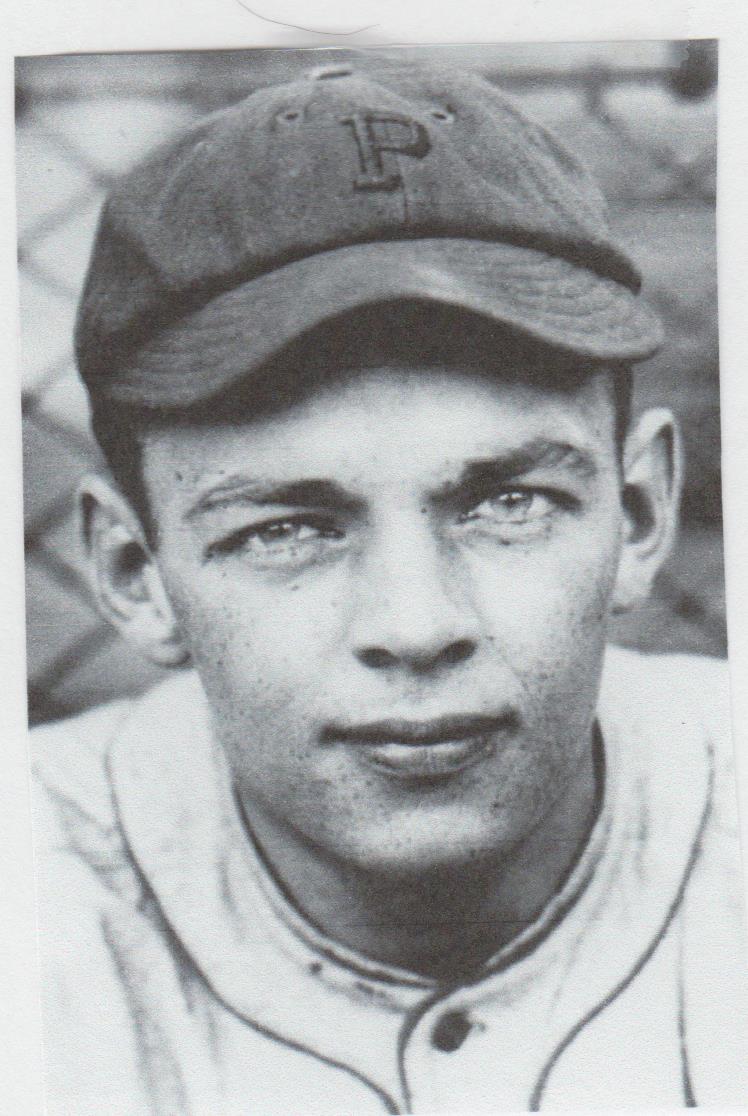

Al Mamaux

During the years before American entry into World War I, Pittsburgh native Al Mamaux was a hometown athletic prodigy. He first came to public attention as a gridiron and pitching standout at Duquesne University in Pittsburgh. Staying local when he turned baseball professional, the hard-throwing right-hander thereafter posted back-to-back 21-win seasons for the Pittsburgh Pirates. And all of this was done before he had reached age 23. Such youthful accomplishments drew raves from sports-page luminaries like Grantland Rice and F.C. Lane, and renowned New York Giants manager John McGraw was an open Mamaux admirer. Meanwhile, other pundits favorably compared the baby-faced hurler to no less than hurling icons Christy Mathewson, Walter Johnson, and Grover Alexander.

During the years before American entry into World War I, Pittsburgh native Al Mamaux was a hometown athletic prodigy. He first came to public attention as a gridiron and pitching standout at Duquesne University in Pittsburgh. Staying local when he turned baseball professional, the hard-throwing right-hander thereafter posted back-to-back 21-win seasons for the Pittsburgh Pirates. And all of this was done before he had reached age 23. Such youthful accomplishments drew raves from sports-page luminaries like Grantland Rice and F.C. Lane, and renowned New York Giants manager John McGraw was an open Mamaux admirer. Meanwhile, other pundits favorably compared the baby-faced hurler to no less than hurling icons Christy Mathewson, Walter Johnson, and Grover Alexander.

Sadly for Mamaux, his time at baseball’s pinnacle was fleeting. Immaturity, arm problems, and the distraction of a budding show-business career reduced his effectiveness, and Al’s major-league days were behind him while he was still a relatively young man. Still, he did not recede entirely from the limelight. Over the next 20 years, his name would remain in newsprint as an International League pitching ace, a pennant-winning minor-league manager, and a successful college baseball coach. All the while, Mamaux, billed as the “Golden Voice Tenor,” filled his offseasons with vaudeville, night-club, and banquet appearances. Even in his senior years Al Mamaux remained active and engaged – until a heart attack brought his interesting and eventful life to an abrupt close in late December of 1962.

Albert Leon Mamaux (pronounced ma-MOO)1 was born on May 30, 1894 in Dormont, then a leafy preserve of the Pittsburgh well-to-do.2 He was the oldest of three sons born to John J. Mamaux (1874-1942), a millionaire businessman known locally as “The Awning King,” and his wife, Julia (nee Wiseman, 1874-1945).3 Of French Catholic stock, the Mamaux family built its fortune upon the company founded by Al’s great-grandfather Eugene Mamaux, an immigrant seaman who converted his talents as a sail maker into the mass production of the wagon covers and tents required by the Union Army during the Civil War.4 In time, his sons Albert and Isaac expanded the business to include the manufacture of awnings, tarpaulins, pennants, flags, and just about anything else made of heavy-duty or waterproof cloth. By the 1880s, the financial success of the A. Mamaux & Sons had placed the family among Pittsburgh’s moneyed elite.5

When his turn came, John Mamaux succeeded his father as company president. Important for our purposes is the fact that both Al’s grandfather and his father were avid baseball fans.6 Indeed, John Mamaux was reputed to have once been a star semipro pitcher, and he manifested sporting ambitions for his oldest son almost from the moment of his birth.7 Al began playing sandlot ball during his parochial-school days, and continued through high school at Duquesne Prep. The 12-0 pitching record he posted in his sophomore year at Duquesne University8 and dominant performances hurling in a local semipro league9 hastened his entry into the professional ranks at age 18.

Accounts vary regarding how Mamaux got his start. Some reports indicate that Al’s grandfather used his acquaintance with Pittsburgh Pirates owner Barney Dreyfuss to get the youngster a contract.10 Others relate that Al did everything himself, walking uninvited into an offday Pirates workout and impressing manager Fred Clarke when given the chance to show his stuff.11 Whichever the case, Al “wound up in a Pirates uniform at Pittsburgh during the final game of the [1912] season.”12 But he saw no action in that contest.

Mamaux was re-signed by Pittsburgh in early 1913 and, after an impressive stint in the Pirates’ spring camp, was sent to the Fort Wayne Champs of the Class B Central League for seasoning. After he lost his first two starts for Fort Wayne, Al was demoted to the Huntington Blue Sox of the Class D Ohio State League. Pitching for the worst-hitting team in the circuit,13 he performed well but struggled to eke out a winning (18-16) record. Mamaux’s experience with Huntington was typified by the one-hitter he lost 1-0 to Lexington in July and the 1-0 perfect game he threw at Maysville the following month. All the while, Pittsburgh boss Dreyfuss was keeping a close eye on the hometown prospect, telling Pirates beat writer A.R. Cratty, “[T]he [Mamaux] boy showed handsomely in the Spring and if he takes the game seriously he should rise well in the profession.”14 Pleased with youngster’s minor-league progress, the Pirates recalled Mamaux late in the season.

On September 23, 1913, 19-year-old Al Mamaux made his major-league debut, coming on in relief of fellow call-up John Scheneberg in a 6-1 loss to Brooklyn. In three innings of work, Al pitched creditably, allowing two hits and one run while striking out two. Thereafter, the Pirates reserved him for the 1914 season.15 When he returned to training camp the following spring, Mamaux attracted attention as much for his appearance and manner as he did for his pitching. As befitted a son of privilege, Mamaux dressed well and expensively, and he seemed self-assured and at ease, even among veteran Pirates players. And to much dinner-table delight, he was not at all reluctant to break out a beautiful high tenor singing voice. All in all, Mamaux was, in the estimation of a Boston newspaper, “a golden kid.”16

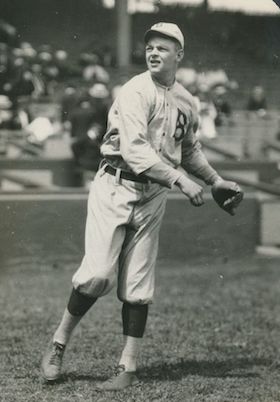

Happily for manager Clarke, Mamaux also displayed pitching talent. At 6-feet and 167 pounds,17 the slender youngster appeared almost frail. But he threw exceptionally hard, with fluid mechanics and a hop at the end of his fastball. He also showed excellent control. Retained on the roster as a second-line hurler, Mamaux was used sparingly during the 1914 season, but pitched well when handed the ball. Given his first major-league start on July 11, Al registered a three-hit, 3-1 victory over Philadelphia, the first of many over his favorite pigeon. At the campaign’s end, his record stood at 5-2, with a fine 1.71 ERA/1.032 WHIP in 13 appearances for the seventh-place (69-85) Pirates. In addition to gaining needed game experience, he had also enjoyed the company of his grandfather that season. Wealthy and retired from day-to-day operation of the family business, Albert Mamaux had taken to accompanying the Pirates on road trips. Fortunately for all concerned, the elder Mamaux was an amiable man and well-liked by the other Pittsburgh players.18

His rookie season had gone well for Al, but serious trouble was brewing on the domestic front. Father John Mamaux had long had a roving eye, the cause of several “lively public scenes” with his wife.19 That October, Julia Mamaux caught her husband and “a dashing Detroit widow” stepping out of the elevator of a New York City hotel, and proceeded to give him a thorough thrashing with a whip (he said)20 or her umbrella (she said).21 When John thereafter sued his wife for divorce, the embarrassing details of the incident were widely published and fractured the Mamaux clan, almost all of whom sympathized with Julia. On November 18 Al was arrested for threatening the life of his father, but was quickly bailed out by his grandfather, who, like Al, sided with Mrs. Mamaux.22 The suit was contested by Julia, who accused her husband of adultery, having paresis, and other unpleasantness, and dragged on for 18 months before divorce was finally granted.23 By that time, Al and his father were permanently estranged.

The 1915 season was a signal campaign for young Al Mamaux, a triumph tempered by various trials. Placed in the starting rotation of the pitching-thin Pirates by manager Clarke, Mamaux got off quickly. But with his log standing at 3-1, Al suffered a grievous personal loss: the death of his grandfather in early May. Thereafter, he pitched brilliantly, throwing a shutout against every other club in the National League. By early August, his record stood at a league-best 17-5. A widely syndicated wire service piece extolled the “fine curves, fastball with a wicked hop, and a change of pace that would do credit to Christy Mathewson,”24 while another gushed that young Mamaux was “showing the speed and form of Johnson and Alexander.”25

Also manifesting itself was a self-centered streak. In August, with the Pirates a nonfactor in the NL pennant chase, Al initiated contact with a local rival, the Pittsburgh Rebels of the Federal League. As subsequently related in the press, only the overreaching of Uncle Dick Wiseman on contract terms prevented Mamaux and the Rebels reaching a deal.26 Al then leveraged his marketability into a three-year, $5,000-per-season contract with Pirates boss Barney Dreyfuss.27 Mamaux reacted petulantly to accusations of avarice and disloyalty, insisting that, contrary to public perception of him as a millionaire’s son, he subsisted entirely on his own earnings.28 However valid this defense, Al’s conduct had soured Dreyfuss on him, and, in time, consequences would ensue. For the short term, however, Mamaux’s health became the most pressing team concern. He was plagued by stomach discomfort for much of the season. Appendicitis was diagnosed in early September, with immediate surgery recommended.29 Much to management’s dismay, Mamaux rejected surgery, resolving to finish the season. Enabled by ice treatments, he pitched through October 2, dropping a 3-1 decision to St. Louis in the Pirates’ next-to-last game.

Despite the illness-occasioned late season tail-off in his performance, Mamaux had had a great year. He had posted a 21-8 (.724) record for a fifth-place club that had otherwise gone 52-73 (.416), and was among NL leaders in shutouts (8, tied for second), wins (third), winning percentage (third), ERA (2.04, third), and strikeouts (152, fourth).30 At season’s end, prestigious Baseball Magazine anointed Mamaux one of the game’s new stars,31 while the respected baseball writer F.C. Lane chose Mamaux and Grover Alexander as the pitchers for “the All-American Base Ball Club of 1915.”32

It is unclear whether Mamaux ever had his appendix removed.33 What is more certain is that Al spent much of the offseason pursuing his other ambition: a musical career. His calendar for the winter of 1915-1916 was dotted with singing appearances in the greater Pittsburgh area.34 Unlike the entertainment forays of most ballplayers, Mamaux’s was not a novelty act; he had a fine tenor voice and was a capable violinist, as well. Although he would never become a headliner, vaudeville, night-club, and banquet engagements would provide Al Mamaux an income for decades.35 But show business would have to wait come the spring of 1916.

The new season was a near-reprise of the old, with Al pitching outstanding ball for another noncontending Pirates club. By June syndicated sports sage Grantland Rice was advising readers that “it may be too early now to say that Al Mamaux will be another Mathewson, Johnson, or Alexander. But the Pittsburgh youngster surely is on his way in that direction.”36 Six weeks later, New York Giants manager John McGraw sounded a similar chord. Mamaux is “a wonderful pitcher,” said McGraw. “The youngster is possessed of fine pitching intelligence which works in fine harmony with his great fastball and curve. He ought to be a star for many years, if he does not waste his strength.”37 But Mamaux’s immaturity soon got him in trouble with club management. Although not much of a drinker, Al’s zest for fine food, pretty women, and night-club hopping put him in frequent breach of curfew. By mid-August, first-year Pirates manager Jimmy Callahan had had enough and suspended him.38

Mamaux was restored to the roster in time to complete his second consecutive 21-win season. But his performance had not been as impressive as the previous season. Al remained among NL leaders in wins (fourth), strikeouts (163, third), as well as innings pitched (310, fourth). But now he was also accumulating negative stats. In 1916, he walked more batters (136) and surrendered more earned runs (87) than any other NL hurler, and his 15 losses were seventh-most. Plainly, the 560-plus innings pitched during the past two seasons had begun to exert their toll on his 22-year-old right arm.

In 1917 it quickly became evident that Mamaux was not the pitcher he had been before. He was hit hard by minor leaguers in spring exhibition games, and then went the first six weeks of the regular season without a victory. Finally and with relief help from Elmer Jacobs, Al registered a 3-2 victory over Philadelphia on May 31. Astonishingly, he would win only one more game that season. Meanwhile, Mamaux’s inability to control his appetite was becoming noticeable, with one newspaper headlining a story about the Pittsburgh ace: “Eating Himself Out of Baseball.”39 More bad publicity attended disclosure of a lawsuit pending against Mamaux. He was being sued for $12,000 by the parents of a small boy who had suffered permanent injuries from being run down by Al’s auto in May 1915.40 But Mamaux’s continued pursuit of night life is what got him in real trouble with the club. In late July, Hugo Bezdek, the disciplinarian recently installed as the latest Pirates manager, suspended Al indefinitely for breaking training rules.41 Mamaux responded badly, jumping the Pirates to sign with a club in the semipro Delaware County League. Furious, Pirates boss Dreyfuss immediately placed Mamaux on the ineligible list, and would not take him back when the quickly contrite pitcher tried to return to Pittsburgh. Mamaux would remain blacklisted by the Pirates and thus ineligible to play anywhere in Organized Baseball unless/until he was reinstated by the National Commission, promised Dreyfuss.42 Al’s 1917 season was over, his baseball future now in serious jeopardy.

Adding to the depressing state of affairs for Mamaux (2-11, with a 5.25 ERA) was his selection to the 1917 all-worst nine chosen by Baseball Magazine, the same publication that had named him an All-American only two seasons earlier.43 But neither this unwanted distinction nor his unsettled situation with the National Commission dulled interest in Mamaux, Reportedly, numerous clubs sought to obtain his services over the winter.44 In January 1918, Dreyfuss acceded to Mamaux’s reinstatement – if only to package him in a multi-player deal with the Brooklyn Robins.45 Al immediately got off on the wrong foot with his new employer, rejecting the contract tendered by Brooklyn owner Charles Ebbets (because it contained a $200 pay cut) and briefly held out.46 After signing, Mamaux made only two ineffectual appearances (0-1/6.75 ERA) for the Robins. He then inflicted new damage on his public image by leaving the club to take a defense-industry job needed to avoid World War I military service. While others, including his younger brother John, shouldered arms, shirker Al Mamaux pitched weekend ball for the Fore River club in the Bethlehem Steel Company League.

On January 2, 1919, Al made his first intelligent move in two years: He married longtime fiancée Alice Johnson.47 The stability of their 44-year union and the birth of daughter Alice Marie in 1920 injected some much-needed maturity into the Mamaux makeup.48 And after he was taken back by Brooklyn, Al benefited from the direction of manager Wilbert Robinson, long respected for his astute handling of pitchers. Regrettably, by this time the misuse of his pitching arm during his early Pittsburgh years had reduced Mamaux to a journeyman hurler. Spotting the fastball of yore but mostly relying on pitching savvy and breaking stuff, Al turned in some useful service in 1919 (10-12/2.66 ERA) and 1920 (12-8/2.69), and got to make his sole World Series appearance during the latter year. He pitched four innings of mop-up relief in the championship match lost to the Cleveland Indians.

Although he was still just in his 20s, the major-league career of Al Mamaux was heading toward the finish line. Off to a fast 3-0 start in 1921, he was stricken by a debilitating stomach ailment in May, and spent most of the season recuperating in the mountains. He returned to the Robins the following year, but went 1-4 and was one of 17 Brooklyn players placed on waivers at season’s end.49 Unclaimed, Al returned to Brooklyn in 1923, but was released to the Bridgeport Bears of the Class A Eastern League after five outings (0-2/8.31). Unable to reach terms with Bridgeport, he joined the Reading Keystones of the Double-A International League. An unexpected 17-10 record in 217 innings pitched for the Reading club revived major-league interest in Mamaux. In January 1924 he signed with the New York Yankees. In what would prove his final major-league season, he went 1-1, with a 5.68 ERA in 14 appearances for New York. Thereafter, he was sold to the Minneapolis Millers of the Double-A American Association.50

With only two outstanding seasons to his credit, Mamaux’s major-league numbers are not overly impressive. He went 76-67 (.531), with a 2.90 ERA/1.275 WHIP in 1,293 innings pitched. He struck out 625, while walking 511 batters and hitting 35 more. But still just 30 years old, Mamaux was set to embark upon a remarkable run as a minor-league pitcher and player-manager. Unwilling to uproot his family from the East Coast, Al refused to report to Minneapolis and once again ended up on Organized Baseball’s ineligible list. He therefore spent the summer pitching semipro ball in Queens and Brooklyn. At the Yankees’ behest, Commissioner Landis reinstated Mamaux in January 1926 – so that he could be sold to the Newark Bears.

With only two outstanding seasons to his credit, Mamaux’s major-league numbers are not overly impressive. He went 76-67 (.531), with a 2.90 ERA/1.275 WHIP in 1,293 innings pitched. He struck out 625, while walking 511 batters and hitting 35 more. But still just 30 years old, Mamaux was set to embark upon a remarkable run as a minor-league pitcher and player-manager. Unwilling to uproot his family from the East Coast, Al refused to report to Minneapolis and once again ended up on Organized Baseball’s ineligible list. He therefore spent the summer pitching semipro ball in Queens and Brooklyn. At the Yankees’ behest, Commissioner Landis reinstated Mamaux in January 1926 – so that he could be sold to the Newark Bears.

For the next four seasons, Al Mamaux was the best pitcher in the International League. He went a combined 79-38 (.674), while leading the circuit in ERA in 1926 (2.22) and 1927 (2.60), as well as in victories (25) the latter year. But curiously, Mamaux attracted no reported interest from major-league clubs, the pitching-poor character of the late-1920s game notwithstanding. When Newark skipper Tris Speaker resigned during the 1930 season, Mamaux accepted the reins while continuing his pitching duties, by now mostly in relief. The following season, he guided the sub-.500 club that he had inherited to a 99-69 record and a close second-place finish. Against the odds, Al remained Newark manager when Yankees owner Jacob Ruppert purchased the club in December 1931. Despite lingering chagrin over Maumaux’s refusal to report to Minneapolis six years earlier, Ruppert stated, “A man as successful as [Mamaux] was last year simply had to be reappointed on his record if for no other reason.”51 Al repaid the Colonel for that somewhat grudging endorsement by leading Newark to the capture of the IL crown. The Bears then defeated the Minneapolis Millers in the 1932 Little World Series. On the way to guiding Newark to a repeat pennant in 1933, the 39-year-old pitcher-manager gave himself a rare start in a June exhibition game and threw a two-hit shutout at the Yankees. But Mamaux proved expendable when Yankees brass needed a place to consign the managing aspirations of an aging Babe Ruth. Al was released as Newark manger in January 1934, having posted a 310-190 mark in his three full seasons at the helm.52

In 1934 Mamaux kept himself busy supervising the liquor department of a large Newark store, managing a local semipro nine, and fulfilling singing engagements.53 The following year, Al was back in harness taking over for Johnny Evers as manager the Albany Senators of the International League. But this time he proved unable to summon his former managerial magic. By one account, the highlight of two last-place Albany finishes was the on-field wedding of a Senators player, with skipper Mamaux crooning “O Promise Me” to the happy couple.54 Fired at the end of the 1936 season, Mamaux lobbied unsuccessfully for the vacant Montreal Royals manager job. Then, employment came from an unexpected quarter: Seton Hall College (now University) in South Orange, New Jersey. For six years, Al was a highly successful college baseball coach, going 69-19 (.795), with an undefeated squad in 1942.

When Seton Hall suspended its baseball program for the duration of World War II, Mamaux became the director of recreation for the Federal Telephone and Radio Corporation in Newark, running baseball clinics for local youth in the summer and talking up the game on the winter banquet circuit. After the war, the Mamauxs moved to nearby Bloomfield, while Al worked in sales. Although now out of baseball, he was not forgotten by the game. In 1951 Mamaux was inducted into the International League Hall of Fame.55 Five years later, he and Alice relocated to the Los Angeles area, presumably to be close to their now-married daughter. Al was still involved in youth baseball and employed part-time as an amusement-park security guard when stricken by a fatal heart attack on December 31, 1962. Death was formally pronounced at Santa Monica Hospital.56 Albert Leon Mamuax was 68. Following funeral services, his remains were interred in Forest Lawn Memorial Park, Hollywood Hills. Survivors included his wife Alice,57 daughter Alice Marie Baumeister, and brother John J. Mamaux Jr. In the decades that followed, the memory of Al Mamaux was preserved by posthumous induction into the sports halls of fame of Seton Hall (1975) and Duquesne University (1988).

Acknowledgments

The writer is indebted to Len Levin and Alan Cohen for their editorial and fact-checking assistance.

Sources

Sources for the biographical information contained herein include materials in the Al Mamaux file at the Giamatti Research Center, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Cooperstown, New York; Mamaux family posts on Ancestry.com; certain of the newspaper articles cited below; and particularly, a detailed Mamaux family history viewable online at homes.amplex.net/mahaffey/Mamaux.html; The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, 2d ed., Lloyd Johnson and Miles Wolff, eds. (Durham, North Carolina: Baseball America, Inc., 1997). Statistics have been taken from Baseball-Reference.

Notes

1 According to the Salt Lake Telegram, April 8, 1917, and Wilkes-Barre (Pennsylvania) Times-Leader, April 12, 1917. See also, The Baseball Name Pronunciation Project, viewable online at http://jkkelley.org/the-baseball-name-pron-project/#section-M. The Baseball-Reference entry for Al Mamaux similarly provides the ma-MOO pronunciation for his surname.

2 In 1909 Dormont seceded from the city of Pittsburgh and has been a separate municipal entity ever since.

3 Al’s younger brothers were John J. Mamaux Jr. (1896-1971) and William H. Mamaux (1906-1919).

4 As per “The Lineage of the Magnificent Nine,” a detailed history of the early generations of the Mamaux family in America, posted online at http://homes.amplex.net/mahaffey/Mamaux.html.

5 A. Mamaux & Sons survives to this day, although the business is now located in nearby McKees Rocks, Pennsylvania, and is no longer in Mamaux family hands. Mamaux Awning & Tent Manufacturing Company, a longtime rival formed by Isaac Mamaux after a family falling-out in the 1880s, remained in business until 1956.

6 The Mamauxs took pride in their supply of the World Champions banner for the 1909 Pittsburgh Pirates.

7 As reported in the Cleveland Plain Dealer, July 11, 1915, Kansas City Star, July 15, 1915, Kalamazoo (Michigan) Gazette, August 15, 1915, and elsewhere.

8 As per the Pittsburgh Dispatch, August 11, 1915, and a player index card in the Al Mamaux file at the Giamatti Research Center.

9 In the fall of 1911, 17-year-old Al Mamaux established his local reputation by pitching the Wilkinsburg club to the championship of the Alleghany County League.

10 As per the Lexington (Kentucky) Herald, August 15, 1915. The Philadelphia Inquirer, August 6, 1916, attributed Al’s signing to his father’s intervention with Dreyfuss.

11 See John J. Ward, “The Million Dollar Kid,” Baseball Magazine, October 1915. See also, Sporting Life, August 21, 1915, and the Wilkes-Barre Times-Leader, September 4, 1915.

12 As per Sporting Life, October 5, 1912.

13 As July began, Huntington’s .221 team batting average was by far the lowest in the Ohio State League. See league stats published in the Lexington Herald, July 1, 1913.

14 Sporting Life, August 23, 1913.

15 As reported in Sporting Life, October 14, 1913.

16 See the pseudonymous Bob Dunbar sports column in the Boston Journal, July 23, 1914.

17A prodigious eater, Mamaux would soon fill out to the 185-190 pounds that he carried for most of his major-league career. During 1920 spring training, a much-anticipated eating contest between Mamaux and well-fed New York Yankees outfielders Ping Bodie and Babe Ruth was aborted when their respective managers got wind of the affair, according to the Anaconda (Montana) Standard, April 6, 1920.

18 As per Sporting Life, May 22, 1915, in reporting grandfather Mamaux’s recent death.

19 According to the Philadelphia Inquirer, October 1, 1916.

20 As per the Duluth (Minnesota) News-Tribune, November 15, 1914, and Seattle Times, November 29, 1914.

21 Philadelphia Inquirer, July 21, 1916.

22 As reported in the Boston Herald, November 20, 1914. The ultimate disposition of the Mamaux threatening charge is unknown, but such matters often end in declination to prosecute/dismissal.

23 As reported by the Philadelphia Inquirer and Wilkes-Barre Times-Leader, July 21, 1916. John Mamaux subsequently married this dashing widow, for which he was ostracized socially by the rest of the Mamaux family. John remained, however, the president and principal shareholder of A. Mamaux & Sons.

24 As published in the Daily (Springfield) Illinois State Register and Omaha World-Herald, August 15, 1915.

25 See the Lexington Herald, August 19, 1915.

26 See the Boston Herald, August 31, 1915, and Sporting Life, August 28 and September 4, 1915.

27As per the Springfield (Massachusetts) Daily News and Wilkes-Barre Times-Leader, August 27, 1915, and Sporting Life, October 23, 1915.

28 As previously reported in the Philadelphia Public Ledger, August 1, 1915. See also, the Boston Journal, August 11, 1915. There was some truth in Mamaux’s protestations. Although he had been among the beneficiaries of his grandfather’s will, Al’s estrangement from father John Mamaux cut him off from most family funds. Thus, while he remained comfortable by baseball-player standards, Al Mamaux nevertheless had to earn a living during his adult life.

29 As reported in the New Orleans Times-Picayune, September 8, 1915, Springfield (Massachusetts) Union, September 16, 1915, Washington (D.C.) Evening Star, September 18, 1915, and elsewhere.

30 In 1915, the major-league leader in virtually all pitching categories was Grover Alexander of the NL pennant-winning Philadelphia Phillies. Alexander’s 31-10/1.22 ERA/241 strikeouts pitching line was arguably the finest of his Hall of Fame career.

31 See J.C. Kofoed, “New Stars of 1915,” Baseball Magazine, October 1915.

32 Announced in Baseball Magazine, December 1915.

33 An assumption that he had undergone surgery was reflected in some reportage, but the Trenton Evening Times, May 30, 1916, laboring to amuse, reported that “although an operation was recommended, [Mamaux] … dodged the cut-ups who wanted to explore his department of interior.”

34 As reported in the Washington Evening Star, February 13, 1916, Baltimore Sun, July 17, 1916, and Boston Journal, August 3, 1916. Although less than thrilled by Mamaux’s vaudeville and night-club appearances, Pirates management deemed them preferable to Al’s other offseason pastime – playing semipro football.

35 As embodied in a 1932 Boston Herald advertisement, many Al Mamaux appearances would take place between screenings of an RKO motion picture. For years, he also did a song-and-dance act with ex-NL pitcher Jesse Petty.

36 As published nationwide. See, e.g., the Cincinnati Post, June 9, 1916, Augusta (Georgia) Chronicle, June 11, 1916, and Charlotte Observer, June 13, 1916.

37 As reported in the Kansas City Star, July 18, 1916, San Diego Union, August 4, 1916, and The (Portland) Oregonian, August 16, 1916.

38 As reported in the Boston Herald, August 20, 1916, Boston Journal and Riverside (California) Daily Press, August 21, 1916, and elsewhere. Simultaneously, the Pirates released reserve outfielder Dan Costello, Mamaux’s nighttime partner-in-mischief.

39 Harrisburg (Pennsylvania) Patriot, June 12, 1917.

40 As reported in the Colorado Springs (Colorado) Gazette, June 17, 1917. The outcome of the suit is unknown but, as with most civil litigation, it was likely settled out of court.

41 As reported the New Orleans Item, July 23, 1917, Elkhart (Indiana) Truth, July 27, 1917, and elsewhere.

42 As per the Fort Worth Star-Telegram and Tulsa World, August 20, 1917, and Washington Evening Star, August 21, 1917.

43 See W.R. Hoefer, “The All-Star Cellar Champions,” Baseball Magazine, December 1917. Joining Mamaux as the magazine’s worst pitchers for 1917 were Burleigh Grimes (3-16/Prates), Earl Hamilton (0-9/Browns), and Joe Boehling (1-6/Indians).

44 According to syndicated sportswriter Jack Veiock in the Denver Post, December 11, 1917.

45 On January 9, 1918, Pittsburgh traded Mamaux, pitcher Burleigh Grimes, and infielder Chuck Ward to Brooklyn in exchange for second baseman George Cutshaw and outfielder Casey Stengel.

46 As per the Baltimore American, February 4, 1918, and Evansville (Indiana) Courier and Press, February 7, 1918.

47Al’s engagement to the Brooklyn model and actress had been announced two years earlier. See, e.g., the Denver Post and Kalamazoo Gazette, March 9, 1917, and (Cheyenne) Wyoming State Tribune, March 14, 1917.

48Nationally published photos of Al with his good-looking wife (see, e.g., the Evansville Courier and Press, May 9, 1919, Anaconda Standard, May 10, 1919, and Pueblo (Colorado) Chieftain, May 11, 1919) or beaming alongside baby Alice Marie (see e.g., the Fort Wayne News Sentinel, April 29, 1921, Dallas Morning News, May 15, 1921, and Aberdeen (South Dakota) American, June 6, 1921) served as tonic for Mamaux’s reputation with baseball fans.

49 As reported in the Charlotte Observer, September 28, 1923, and Denver Rocky Mountain News and Evansville Courier and Press, September 29, 1923.

50 As reported in the (Little Rock) Arkansas Gazette and Miami Herald, January 10, 1925, and elsewhere.

51 Springfield (Massachusetts) Republican, December 4, 1931.

52 The Newark managing job was reportedly offered to Ruth in November 1933. See, e.g., the Washington Evening Star, November 23, 1933. As it turned out, the 39-year-old Ruth played for the Yankees in 1934. The Newark post was eventually given to former Yankees pitcher and manager Bob Shawkey.

53 As per I.C. Brenner, “Al Mamaux Yodels, Sells Rye, Thinks of Baseball,” Omaha World-Herald, April 4, 1934.

54 As recalled years later by Harold Lubell, “Ex-Bear Manager Mamaux Had Some Big Days in J.C.,” Jersey Journal (Jersey City), January 4, 1963.

55 Inductees were selected by the sportswriters who covered the International League. Mamaux posted a 132-65 (.670) record pitching for Reading and Newark, and went 495-480 (.508) as skipper in Newark and Albany.

56 According to his death certificate, Mamaux had suffered from heart disease.

57 Alice Johnson Mamaux died in November 1963 and was interred beside her husband at Forest Lawn.

Full Name

Albert Leon Mamaux

Born

May 30, 1894 at Pittsburgh, PA (USA)

Died

December 31, 1962 at Santa Monica, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.