Pete Alexander

Had Grover Cleveland Alexander been a writer, the French would have called him a poete maudit, a cursed poet. Alexander had within him the greatness and the frailty that make for tragedy. Except for Ty Cobb among his contemporaries, no other player had to cope with so many personal demons. With Cobb and Christy Mathewson, Alexander is one of the most complex players of the Deadball Era.

Had Grover Cleveland Alexander been a writer, the French would have called him a poete maudit, a cursed poet. Alexander had within him the greatness and the frailty that make for tragedy. Except for Ty Cobb among his contemporaries, no other player had to cope with so many personal demons. With Cobb and Christy Mathewson, Alexander is one of the most complex players of the Deadball Era.

The only ballplayer named for a sitting United States president and portrayed on film by a future one (Ronald Reagan in The Winning Team) was born February 26, 1887, in the tiny farming community of Elba, Nebraska. He was one of thirteen children (twelve boys), the sixth of eight to survive into adulthood, born to the former Margaret Cootey and William Alexander.

Life on the Nebraska plains was harsh, as the infant and child deaths in the Alexander family amply prove. The Alexander farm was self-sufficient, however, and there was always enough food. Alex-called “Dode” by family and folks around Elba and St. Paul-considered himself “an average farm boy” and described his youth as “more or less a matter of long days of work and short nights of sleep.” He acquired a reputation as a corn shucker, a task his father credited with giving him the powerful right wrist that made his curveball so deadly. Alex developed his control throwing stones at clothespins or chickens (if his mother needed to fill the dinner pot). To be fair, he gave the chickens a running start. Despite the hardships, he graduated from St. Paul High School.

William Alexander hoped his son would study law as had his presidential namesake, but Dode wasn’t interested. Instead, he became a lineman with the telephone company so he could play ball on the weekends. Acquiring a local reputation as a pitcher, he signed with Galesburg (Illinois-Missouri League) for the 1909 season. After a slow start, he went 15-8 with an estimated ERA of 1.36 and 6 shutouts. On July 22, pitching in Galesburg against Canton, he threw the only no-hitter of his career, a 2-0 masterpiece in which he struck out ten, walked one, and hit a batter. A few days later, he beat Macomb, 1-0, in eighteen innings while allowing eight hits, hitting a batter, walking no one, and striking out nineteen.

In late July, however, he suffered an injury that ended his first season prematurely and cast doubts about his future. Alex was running from first to second trying to break up a double play when the shortstop’s throw hit him square in the right temple. Reports vary, but he was unconscious between thirty-six and fifty-six hours. He awoke suffering from double vision, which he endured through the fall and winter into the next spring. The double vision disappeared as suddenly as it came, and he was able to pitch again. The short-term effect, then, was relatively negligible. The long-term effect of the blow might have been the epilepsy that would do much to make the last half of his life a living hell.

The 1910 season got off to a bizarre start for Alexander. Galesburg sold him to Indianapolis, who, having heard of Alex’s double vision and believing that Galesburg had been too anxious to let him go, sold him to Syracuse (New York State League) without even giving him a look. Syracuse prospered from the gift. Alex went 29-11 with an ERA of 1.85. Thirty-one complete games and 217 strikeouts against only 74 walks in 345⅔ innings made for a nice bonus. Particularly eye-popping was the number of shutouts—15. He put to rest the rap in the Syracuse press that he was a bit soft on July 20 by beating Wilkes-Barre in two well-pitched complete games. He resolved any other questions about his stamina with a string of 52 consecutive scoreless innings and 6 shutouts that only the end of the season stopped.

Alexander was clearly ready for the majors, but the Phillies were particularly interested in George Chalmers of Scranton. They got Chalmers for $3,000 and, as insurance, drafted Alex from Syracuse for $500. Chalmers struggled over seven seasons, but Philadelphia’s investment in Alex paid a better dividend.

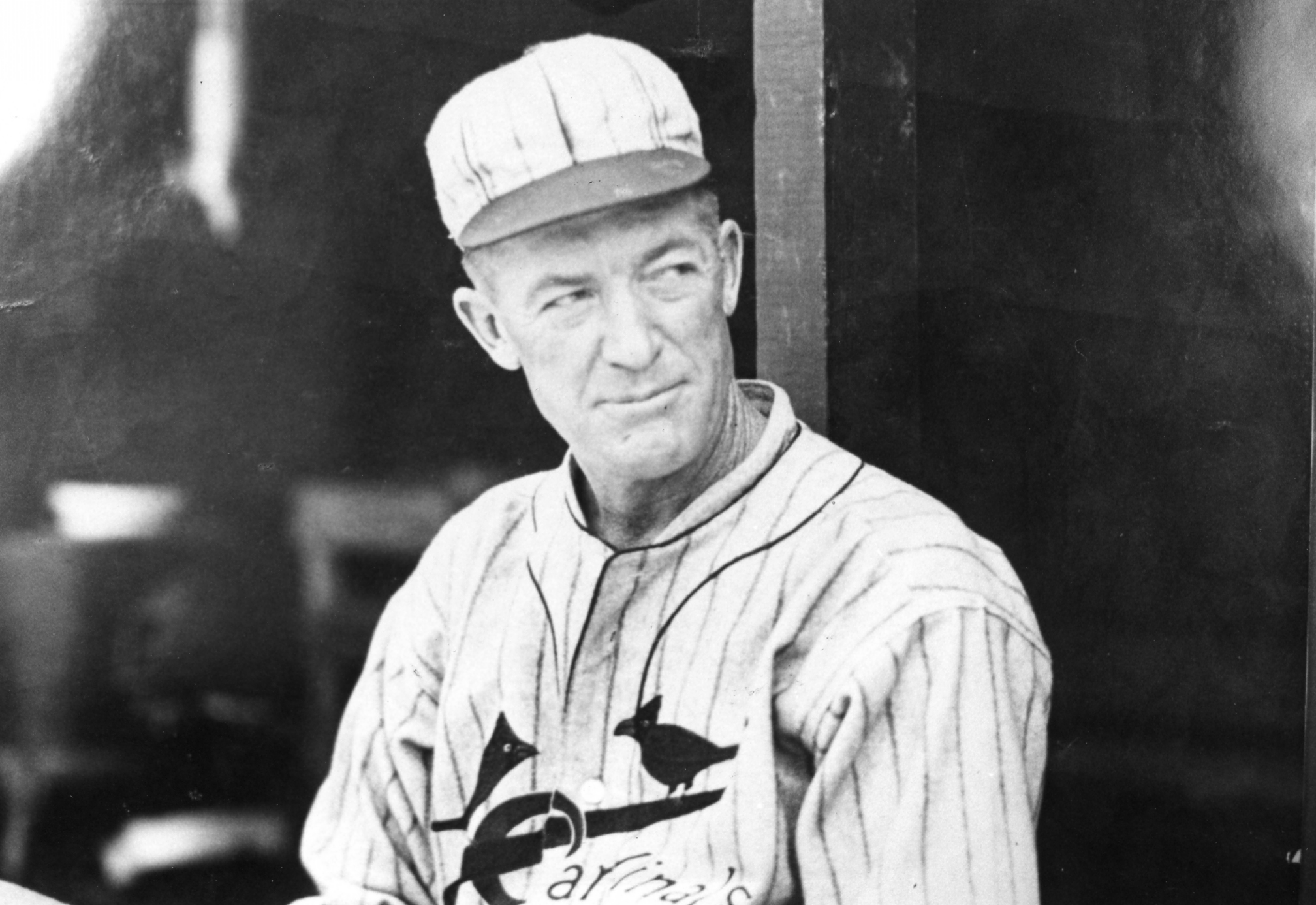

Alex caught the National League by surprise. He didn’t look like a pitcher, as did his older contemporaries Christy Mathewson and Walter Johnson. All three were in the six-foot-one range, but whereas Alexander was a wiry 185 pounds, Mathewson and Johnson were a hard, chiseled 195 to 200 pounds. Matty and Walter had a majestic, almost regal way about them while Alex always had an unhurried shuffle, a uniform that never seemed to fit just right, and a cap that looked a size too small and stood on his head at a precarious tilt. All that changed when he pitched. He was the picture of grace and efficiency—often completing games in ninety minutes—with a smooth, usually sidearm delivery, possessing excellent control of a sneaky fastball and a devastating curve.

Alexander didn’t impress anyone at spring training except catcher Pat Moran, who saw something in him and persuaded the team to take the new pitcher north. He got to show his potential in the last game of the pre-season City Series, pitching five scoreless innings against the defending World Series champion Athletics. Alex debuted in Boston on April 15, losing a 5-4 decision on an unearned run in the ninth. He picked up his first win on April 26, beating Brooklyn in the first game of a doubleheader, 10-3.

Alex’s performance in 1911 is arguably the greatest season by a rookie pitcher in the twentieth century—28-13 with a 2.57 ERA. Twenty-eight wins led the league and remain the twentieth-century record for rookies. One of his biggest wins came in Boston against Cy Young in September, a one-hit 1-0 shutout. His 227 strikeouts, good for second in the league, stood as the record for rookies until Herb Score gunned down 245 for the Indians in 1955. He also led the league in complete games with 31, innings pitched with 367, and shutouts with 7 (four of them consecutive). His ERA was good enough for fifth. Pitching relief occasionally between starts, he picked up three saves. All of this came as part of a 79-73 team.

The Phillies in 1912 reversed their numbers to 73-79 and took Alexander down a bit with them. He went 19-17 with a 2.81 ERA but led the league with 195 strikeouts and 310 innings pitched. Philadelphia improved to second, well behind the Giants, in 1913, Alex contributing a 22-8 mark and a league-best 9 shutouts. Consistently inconsistent, the Phils fell to sixth in 1914 with a 74-80 slate. The fall was no fault of Alexander’s; he went 27-15 with a 2.38 ERA, leading the league in wins, innings pitched (355), strikeouts (214), and complete games (32).

The Phillies decided to make a change. Out went skipper Red Dooin. Enter Pat Moran, the good-field-fair-hit catcher who had persuaded the team to give Alex a real chance. Moran, an extraordinary manager who was building a Hall of Fame career until he died suddenly during spring training in 1924, was a genius at getting the absolute best out of his pitchers, as Alexander, Eppa Rixey, and a number of lesser talents had their finest seasons under him. Grover Cleveland Alexander was about to become Alexander the Great.

Beginning with the 1915 season, Alexander embarked on a three-year reign of terror over the National League. He went 31-10 to lead the league in wins and achieved his first pitcher’s Triple Crown, leading the league with a microscopic 1.22 ERA and a career-high 241 strikeouts. He led the league in every important pitcher’s category: innings pitched (376⅓), complete games (36), winning percentage (.756), and shutouts with an incredible 12, a figure that stood as the National League record for one year. To make his domination of hitters humiliating as well as complete, he pitched four one-hitters. The first one-hitter, a 3-0 win in St. Louis on June 5, was the closest Alex ever came to a major-league no-hitter, as shortstop Artie Butler singled past Alex’s head with two down in the ninth.

Behind Alex’s leadership, the Phillies edged out the Braves by one game and headed into the World Series with the Red Sox. He defeated Ernie Shore, 3-1, in Game One as both pitched a complete game. Dutch Leonard beat Alex, 2-1, in Game Three as Duffy Lewis singled in the bottom of the ninth to score Harry Hooper. Moran hoped to use Alexander in Game Five, but Alex felt worn out from the long season, and the Phillies lost a heartbreaker, 5-4, behind Erskine Mayer and Rixey.

Alexander rebounded from the disappointment of the Series loss with another Triple Crown: 33-12, 167 strikeouts, and a 1.55 ERA. He reached a career-high and league-leading 389 innings, 45 starts, and 38 complete games—and 16 shutouts. With the shutouts Alex reached two pinnacles: He’s the only National League pitcher to reach double figures twice in shutouts, and he holds the major league record for shutouts by three over Jack Coombs in 1910 and Bob Gibson in 1968. Coincidentally, he pitched his record-breaking 14th shutout on September 1, a 3-0 gem over Brooklyn’s Jack Coombs. Making his shutout record yet more astonishing is that he attained it pitching half his games in tiny Baker Bowl, a graveyard for pitchers. Alex’s heroics weren’t enough for the Phillies, who improved their won-lost record from the previous year but slid in 2½ games behind Brooklyn.

Philadelphia remained in second in 1917 albeit ten games behind the Giants, but it wasn’t Alexander’s fault. He went 30-13 and with 200 strikeouts to lead the league along with a 1.83 ERA and a league-best 8 shutouts, 44 starts, 34 complete games, and 388 innings pitched. Under the rules of 1917, Alexander was awarded the ERA title because he pitched 10 or more complete games. However, under today’s rules, the award goes to the Giants’ Fred Anderson, who compiled his 1.44 ERA in 162 innings with a nondescript 8-8 record and fewer than 10 complete games.

With the war raging in Europe and the United States having entered the fray the previous April, the Philadelphia front office carried off one of the most cynical acts in baseball history. Gambling that Alexander would be drafted into the army, on December 11, 1917, they sent Alex and catcher Bill Killefer to Chicago for Mike Prendergast and Pickles Dillhoefer and $55,000.

Adapting to Chicago nicely, a $5,000 bonus from Charles Weeghman helping the process, Alex won two of his three decisions in 1918, all complete games, with a 1.73 ERA when the army came calling. Philadelphia’s gamble paid off. Ironically, the Cubs won the pennant anyway behind the Triple Crown pitching of southpaw Jim Vaughn.

Alexander invested his bonus in Liberty Bonds and reported for duty at Fort Funston, Kansas. On May 31 he married Amy Marie Arrants of Omaha, whom he’d met on a blind date several years before when she was visiting friends in St. Paul.1 A sergeant assigned to the 89th Division and the 342nd Field Artillery, Alex shipped out from New York on June 28 and arrived in Liverpool on July 9. His unit went to the front late in July.

Many men survived the war, but they didn’t recover from it. One of the many cruel coincidences of the war is that it destroyed the two greatest National League pitchers of the Deadball Era, if not of the twentieth century, Christy Mathewson and Grover Cleveland Alexander.

Alexander spent seven weeks at the front under relentless bombardment that left him deaf in his left ear. Pulling the lanyard to fire the howitzers caused muscle damage in his right arm. He caught some shrapnel in his outer right ear, an injury thought not serious at the time but which may have been the progenitor of cancer almost thirty years later. He was shell-shocked. Worst of all, the man who used to have a round or two with the guys and call it a day became alcoholic and epileptic, a condition possibly caused by the skulling he’d received in Galesburg. Alex tried to cover up his epilepsy, using alcohol in the mistaken belief that it would alleviate the condition. Living in a world that believed epileptics to be touched by the devil, he knew it was more socially acceptable to be a drunk.

A human wreck, Alexander returned to the Cubs on May 11, 1919. Working his way back into pitching shape, he dropped his first five decisions. Once he got turned around, Alex finished 16-11 for a distantly third-place team and led the league with 9 shutouts and a sparkling 1.72 ERA. His ERA remains the lowest for a Cub pitcher since the team began playing in Wrigley Field. He transcended his fifth-place team in 1920 with his last Triple Crown season: 27-14 with 173 strikeouts and a 1.91 ERA. In addition, he led the league in starts (40), complete games (33), and innings pitched (363⅓) and threw in 7 shutouts and 5 saves.

From 1921 on, Alexander was a different pitcher, depending on finesse and pinpoint control, never striking out a hundred batters again, walking very few, having ERAs over three for the first time in his career, but still winning more than he lost. Alcohol was taking over his life, as he drank to relive the past, forget the present, and forestall the future. No longer a great pitcher, he was still a very good one, capable of picking up 22 wins in 1923 and setting a major-league record by starting the season pitching 52 consecutive innings before issuing a walk.

After the Cubs finished last in 1925, the front office brought in a career minor-leaguer named Joe McCarthy to manage in 1926. McCarthy, who would become a great manager, thought Alexander’s drinking was hurting the team. Alex made clear from the start that he had no use for McCarthy. With Alex muddling along at 3-3, the Cubs traded him to St. Louis for the waiver price on June 22. Legendary Cardinals player-manager Rogers Hornsby, wanting to win the pennant, figured Alex could help him and tolerated the drinking as long as it didn’t interfere with business. Alex helped, his 9-7 effort providing the margin in St. Louis’ two-game lead over Cincinnati.

The 1926 World Series, pitting the Cardinals against a powerful Yankee team featuring veteran bombers Babe Ruth and Bob Meusel and young guns Lou Gehrig and Tony Lazzeri, cast the Alexander legend in stone. Alex pitched complete-game wins in Games Two and Six before the climactic seventh game. Alex entered the game to relieve Jesse Haines in the seventh inning with bases loaded, two out, and the Cardinals hanging on to a 3-2 lead. He struck out Lazzeri, held the lead, and the Cards were champs. Whether he was hung over, drunk, or sober — Alex and Amy always maintained he was sober — will probably never be known. Two interesting footnotes to the tale emerge: (1) Alexander, though striking out only 48 batters in 200⅓ innings during the season, struck out 17 Yankees in 20⅓ innings; and (2) Lazzeri, also hiding epilepsy, fell down a flight of stairs to his death during a seizure in 1946.

The 1926 World Series, pitting the Cardinals against a powerful Yankee team featuring veteran bombers Babe Ruth and Bob Meusel and young guns Lou Gehrig and Tony Lazzeri, cast the Alexander legend in stone. Alex pitched complete-game wins in Games Two and Six before the climactic seventh game. Alex entered the game to relieve Jesse Haines in the seventh inning with bases loaded, two out, and the Cardinals hanging on to a 3-2 lead. He struck out Lazzeri, held the lead, and the Cards were champs. Whether he was hung over, drunk, or sober — Alex and Amy always maintained he was sober — will probably never be known. Two interesting footnotes to the tale emerge: (1) Alexander, though striking out only 48 batters in 200⅓ innings during the season, struck out 17 Yankees in 20⅓ innings; and (2) Lazzeri, also hiding epilepsy, fell down a flight of stairs to his death during a seizure in 1946.

Reveling in his Series glory, Alexander enjoyed his ninth and last twenty-win season in 1927, going 21-10 with an ERA of 2.52. He slipped to 16-9 in 1928, pitched his ninetieth and last shutout, and was pounded mercilessly by the Yankees in their Series sweep of the Cardinals. His ninth and last win of the 1929 season, against eight losses, gave him 373, the number he believed put him ahead of Mathewson’s 372 and gave him the National League record for wins. It wasn’t to be, however, as researchers in the 1940s discovered an error in Matty’s 1902 numbers, improving his record from 13-18 to 14-17. The two righthanders, both victims of the war, would be forever linked in the record books. On December 11, twelve years to the day after Philadelphia traded him to Chicago, the Cardinals traded Alexander and Harry McCurdy to Philadelphia for Homer Peel and Bob McGraw—three of the most insignificant players ever connected to a Hall of Famer.

Alex lost all three decisions with Philadelphia in 1930, his first losing record ever, and was released. He tried to continue with Dallas in the Texas League but was ineffective and was soon let go. He pitched a few games over the next three years as a novelty with the House of David team. He was allowed to shave, but since a shot and a beer cost the same as a razor blade, he frequently had a stubble. Failing here, he was out of baseball for good. The coaching position he longed for never materialized because no one wanted to take a chance on him.

The last two decades of Alexander’s life are the picture of a man spinning out of control with nobody able to stop the free-fall. Alex entered various sanitariums seeking help, but nothing worked. He was hooked. Having put up with enough, Amy divorced him in 1929, hoping to shock him to his senses. Roy H. Masonnof of St. Paul filed a $25,000 lawsuit against him in January 1930, charging him with being a “love pirate.” Everybody cooled off, and Alex and Amy remarried in 1931. He shuffled around the country in an odyssey of odd jobs (including a stint recounting his strikeout of Lazzeri in a Times Square flea circus), cheap hotels, boarding houses, and the like. His poverty and inability to straighten out became an embarrassment to the National League. The Alexander file at the Hall of Fame contains a collection of letters exchanged among Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis, National League president Ford Frick, Cardinal president Sam Breadon, and Cardinal general manager Branch Rickey—all of them addressing the question “What to do about Alexander?” They finally settled on the ruse of a National League pension of fifty dollars a month that was actually paid by the Cardinals and sent to whoever was keeping Alex to dole out to him as necessary. That, they hoped, with his small army pension, might keep Alexander from drowning.

Alexander’s desperate situation found relief only in his election to the Hall of Fame in 1938. He pulled himself together enough to go to Cooperstown for the first induction ceremony on June 12, 1939, and thoroughly enjoyed the time with the honorees. It was bittersweet, though, as Alex said in 1944, “I’m in the Hall of Fame, . . . and I’m proud to be there, but I can’t eat the Hall of Fame.”

The Alexanders divorced again in 1941 but remained close. Amy thought Alex never really considered them divorced and said he always sought her advice and friendship. He suffered a heart attack on October 15, 1946, as he was leaving Sportsman’s Park after watching the Cardinals beat the Red Sox in the World Series. In 1947 he was injured in a fall during an epileptic seizure in Los Angeles. He developed cancer on his right ear, necessitating its amputation. Amy thought the cancer might have been sun-related because Alex was fair and got sunburned often. It’s possible, too, that the root of the cancer stemmed from the shrapnel fragments he took during the war and the infection he suffered upon their removal. He made his last public appearance as the Yankees’ guest for Games Three and Four of their World Series sweep of the Phillies. Back in St. Paul after the Series, on November 4 he left his hotel room to mail a letter to Amy telling her he was looking forward to meeting her in Kansas City. He went back to his room and—mercifully—died. He was buried with full military honors in his family’s plot in Elmwood Cemetery outside St. Paul. His death certificate said Alex died of cardiac failure. Amy thought he died in a fall from an epileptic seizure. Either way, having reached the zenith, he had fallen to the depths. Never meeting a batter he couldn’t beat or a bottle he could, pursued by demons one can only imagine, Alexander was the cursed pitcher.

Amy, ever speaking kindly of Alex, died in Los Angeles in December 1979 at age eighty-seven.

An earlier version of this biography appeared in SABR’s “Deadball Stars of the National League” (Brassey’s, Inc., 2004), edited by Tom Simon.

Sources

Grover Cleveland Alexander Files at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in Cooperstown, New York.

Hoie, Bob, Carlos Bauer, et al, eds. The Historical Register: The Complete Major & Minor League Record of Baseball’s Greatest Players. San Diego and San Marino: Baseball Press Books, 1998.

Honig, Donald. The Greatest Pitchers of All Time. New York: Crown Publishers, 1988.

Kavanagh, Jack. Ol’ Pete: The Grover Cleveland Alexander Story. South Bend, Indiana: Diamond Communications, Inc., 1996.

Meany, Tom. Baseball’s Greatest Pitchers. New York: A. S. Barnes, 1951.

_____. Baseball’s Greatest Teams. New York: A. S. Barnes, 1949.

Ritter, Lawrence S. The Glory of Their Times: The Story of the Early days of Baseball Told by the Men Who Played It. New York: Macmillan, 1966.

Schechter, Gabriel. Unhittable! Baseball’s Greatest Pitching Seasons. Los Gatos: Charles April Publications, 2002.

Thorn, John, Pete Palmer, and Michael Gershman, eds. Total Baseball. 7th ed. Kingston, New York: Total Sports Publishing, 2001.

Wilbert, Warren, and William Hageman. Chicago Cubs: Seasons at the Summit. The 50 Greatest Individual Seasons. Champaign, Illinois: Sagamore Publishing, 1997.

Notes

1 Bob Broeg notes in his Foreword to Jack Kavanagh’s Ol’ Pete that Miss Arrants’ name was originally spelled “Amy” and that she experimented with other spellings, including the frequently cited “Aimee.”

Full Name

Grover Cleveland Alexander

Born

February 26, 1887 at Elba, NE (USA)

Died

November 4, 1950 at St. Paul, NE (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.