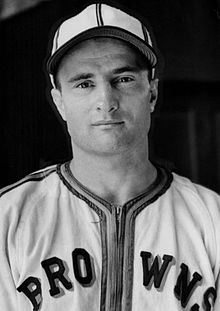

Ellis Clary

Ellis Clary played in the majors for nearly four seasons during World War II, and he had an at-bat during the St. Louis Browns’ only World Series appearance in 1944. Once his playing career ended, he spent six years as a coach with the Washington Senators and more than three decades as a scout for three teams.

Ellis Clary played in the majors for nearly four seasons during World War II, and he had an at-bat during the St. Louis Browns’ only World Series appearance in 1944. Once his playing career ended, he spent six years as a coach with the Washington Senators and more than three decades as a scout for three teams.

Although he stood just 5-foot-8 and weighed no more than 160 pounds, Clary was noted as a quick-tempered brawler as a player. Later, however, he developed a reputation as a wise-cracking and humorous storyteller. “I believe Ellis could make a dog laugh,” former Yankees pitcher Spud Chandler, later a fellow scout, said of Cleary.1

“Clary has a sharp wit,” columnist Bob Addie wrote in 1957, “and his keen satire is more deadly than his fists –which is saying a great deal since he was quite a battler.”2

Ellis Clary — he had no middle name — was born in Valdosta, a town of about 25,000 in southern Georgia, on September 11, 1916,3 to Ira S. and Clara W. Clary. His parents, who were of Irish and Scottish descent, had six sons and a daughter. His sister was several years older, but Ellis was the oldest of the brothers. His father was a lawyer who died when Ellis was 11 years old. His mother struggled to raise them all, and managed the family’s home as a boarding house.4

Although Clary insisted later in life that the family was never desperately poor, money was short, especially during the Depression. “You could get a wagonload of groceries for a dollar,” he told Sporting News columnist Bob Broeg in 1977, “if you knew where to get the dollar.”5

Still, Clary was able to stay in school and became a star athlete at Valdosta High. He also played American Legion baseball.6 Clary was a halfback and kicker on the football team and told Broeg he could have gone on to play college football at Alabama or Florida if he hadn’t decided to pursue a baseball career. He never lost his love of football, however, and was regarded later in life as a walking encyclopedia on the college game, especially the Southeastern Conference.

Clary began his professional career close to home with Americus, Georgia, in the Class-D Georgia-Florida League in 1935 as soon he graduated from high school. He hit .216 as an 18-year-old that season and just .188 in 21 games the next season before moving to Sanford in the Class-D Florida State League. The competition there was more to his liking: He hit .276 in 1936 and .282 in 1937. He was the shortstop on the league’s post-season all-star team. Sanford had an affiliation with the Washington Senators, and he was added to the Nats’ 40-man roster in November 1937.7

When he was with Sanford in 1937, Clary roomed with Early Wynn, who for no particular reason–other than Clary liked the way it sounded–called the pitcher “Gus.” The nickname stuck with the future Hall-of-Famer throughout his career.8

A decent base-stealer, Clary twice led the Florida State League.9 He led the league in runs scored in 1937. At Charlotte in the Class-B Piedmont League in 1938, he again led the league in steals, scored 101 runs, and hit .303.

Although he didn’t make the majors until 1942, he clearly was a legitimate prospect; he also began getting himself in hot water. When Calvin Griffith was managing Washington’s Charlotte farm club in 1938, Clary started a fight with a Durham player that quickly involved others on both teams. Griffith punched a man who had his hands around Clary’s neck. The next thing you know, Griffith was arrested. The man he punched turned out to be the local police chief. That was the first of two times Griffith was charged after Clary punched somebody.10

After 33 games at Springfield in the Class-A Eastern League in 1939, Clary was banished from the team after he climbed into the stands and threw water on a heckler. The Senators sent him back to Charlotte.11

On April 14, 1940, Clary married Myra Webb, an 18-year-old from his Valdosta, Georgia, hometown.12 The couple had the first of their four daughters in the summer of 1943.

At Greenville in the Class-B South Atlantic League in 1940, he hit .308, which is what he was hitting midway through the next season when the Senators promoted him to Chattanooga in the Class A-Southern Association.

Clary was with Chattanooga when he was called up by the Senators in early June 1942. He made his debut on June 7, going two-for-four against the Tigers at Griffith Stadium. He was the Nats’ mainstay at second base for the rest of the season, finishing at .275, although 57 of his 66 hits were singles. Thanks to 45 walks in 291 plate appearances, however, he had an excellent .394 on-base-percentage. His career major-league OBP was a respectable .376.

Clary crowded the plate, almost daring pitchers to throw at him. Several took up the dare. He was beaned twice in 1942. The first one sent him to the hospital. He was often erratic in the field, but his hard-nosed play made him popular with Washington fans. “His teeth were as much a part of his fielding equipment as his glove,” columnist Shirley Povich recalled in July 1954.13

Although Clary had done well enough in the minors to warrant an earlier promotion, owner Clark Griffith said the team was wary of calling him up “because of fear he would be a rebel who would be hard to handle….That wildcat would be a good ballplayer if he would settle down, but he gets in trouble wherever he plays.”14

In 1943, the Senators moved Clary to third base, where he was in the lineup most days. On April 24, Clary led off a game against the Yankees’ Chandler with a double. It was Washington’s lone hit in a 1-0 loss. On May 9 at Griffith Stadium, he got into a brawl with Red Sox catcher Johnny Peacock, who had been taunting him while he was batting. Clary ripped off Peacock’s mask and began pummeling him, setting off a bench-clearing brawl. Both players were fined $100.

On August 18, 1943, with the Senators surprisingly in a pennant race, Clark Griffith shipped Clary and pitcher Ox Miller to the St. Louis Browns for veteran third baseman Harlond Clift and pitcher Johnny Niggeling. Coming after the trading deadline, the deal was technically a waiver transaction but with so many players having been drafted, the league did not object. Clift played just eight games for Washington before an injury ended his season and Washington’s pennant hopes.

Clary had expected to be the Browns’ regular at third base, but by the time he arrived, Mark Christman had replaced Clift and started to hit. “I can’t put you in the game now with Christman going so hot,” Browns manager Luke Sewell told Clary. “Sit around a while, and we’ll see what happens.”15 Christman kept hitting, so Clary stayed on the bench.

Still, Clary never regretted the trade. “For once, the Old Fox was wrong,” he said years later about the trade for Clift, “and I thank him for it.”16 Clary described the 1944 season as “the most fun I had in my life.”17

The Browns’ 1944 club had 18 players, including Clary (bad back), classified as 4-F, physically unfit for the military. They might not have been fit for the military, but they won the Browns’ first and only pennant and met the Cardinals in a crosstown St. Louis World Series. Clary’s only appearance was in the fourth game as a pinch-hitter — he flied out. “What a terrible job it was for Luke Sewell to manage that bunch of hyenas,”’ Clary said at a 50th anniversary reunion of the 1944 team. “They drank anything that would pour.”18

By this time, Clary had become at least part owner of a bottling plant in North Carolina. He reported late to spring training in 1945 after apparently weighing retirement.19 He remained with the Browns through that season, but played sparingly. He hit his only home run in the majors on April 20, 1945, off Ed Lopat in Chicago. Clary’s lifetime average in the majors was .263.

Sent to the minors before the 1946 season, he played regularly for three years with Toledo, the Browns’ top farm club, in the American Association. He continued to play well through 1952, when at age 37, he was voted the Most Valuable Player in the Southern Association as a member of the Chattanooga Lookouts. During a part-season stint with the pennant-winning 1950 Atlanta Crackers, another Southern Association club, he played with 18-year-old slugger Eddie Mathews. His 1953 season with Chattanooga was Clary’s last as a player.

His brawls and temper tantrums were frequent stories in newspapers over the years. In April 1949, playing for Baltimore, Clary was being profanely heckled by a fan behind his team’s dugout. When he told manager Tommy Thomas that he was reluctant to go back on the field, Thomas stepped out of the dugout, pointed out the abuser and told Clary to “go get him.” Clary did, but was stopped by police before he could assault the man. The incident led to suspensions and fines for Thomas and Clary, the resignation of the longtime Baltimore manager and Clary’s departure from the team.20 The next month, Clary was charged with assault for punching a 20-year-old in a traffic dispute.21

With Chattanooga in May the next season, Clary blew up and was ejected after being called out on strikes. When the game ended, he kicked the door to the umpires’ dressing room off the hinges. He was suspended for five days and fined $50.22 Chattanooga soon sent him off to Atlanta for the rest of that season. Back with Chattanooga in 1952, he was suspended for five days and fined after a July 27 rhubarb during which he spit at an umpire.23

Coaching for Washington in May 1959, Clary got into a bench-clearing brawl in Cleveland and punched Jimmy Piersall.24 Managing in the Sally League in 1961, he was suspended for three games for bumping an umpire.25

Coaching for Washington in May 1959, Clary got into a bench-clearing brawl in Cleveland and punched Jimmy Piersall.24 Managing in the Sally League in 1961, he was suspended for three games for bumping an umpire.25

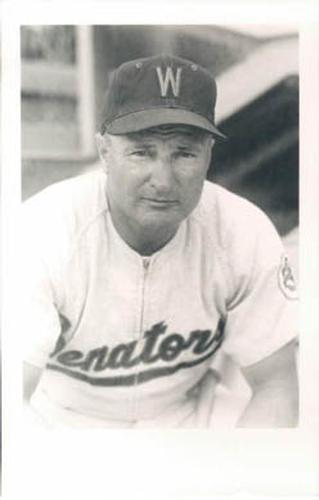

The bulk of Clary’s baseball career was spent with Griffith-owned owned teams in Washington and Minnesota in the American League and Chattanooga and Charlotte in the minors. In addition to parts of two seasons with the Senators, he played for and then managed Charlotte twice, played for Chattanooga twice for nearly five seasons, coached with Washington for six years and scouted for Minnesota for 23 years.

Clary began writing an offseason column for the Valdosta Daily Times in the fall of 1949,26 and was the radio broadcaster for Valdosta high school football games in 1956.27 In 1952, he also opened a pool hall called the Sportsman’s Club in Valdosta.28

After six seasons, Clary was let go as the Senators’ third base coach in October 1960 as the team was moving to Minnesota. Yet his time in uniform had earned him a pension. In 1961, Clary was back in the Griffith fold, managing the Charlotte farm team. He became a scout for the Twins the next season, staying on until Griffith finally sold the team.

The Browns and Cardinals held a reunion in 1964 to mark their meeting in the 1944 World Series. Clary played when the old-timers took the field at Busch Stadium, but complained when Red Schoendienst, who hadn’t come up until 1945, made nice play as shortstop to rob him of a hit.29 Clary also attended a 1984 Busch Stadium ceremony marking the 40th anniversary of the St. Louis series.30

In 1985, Clary began scouting for the White Sox. Then in 1987, Pat Gillick hired him to scout for the Blue Jays. Clary was back in uniform for a while in 1988 as a minor league instructor and then in 1989 at age 72, coaching Toronto’s infielders. He used the opportunity to argue about football and match his predictions against the Blue Jays players. “Most of them can’t pick their brother out of a parade of two-hump camels,” he said.31 Clary returned to scouting with Toronto until he retired in 1993, after the Blue Jays had won two World Series.

Clary nearly died after suffering a severe heart attack while attending a high school baseball all-star game in May 1970. He was revived more than once through the use of an early model defibrillator. He spent six weeks in a Mobile, Alabama, hospital, but made a full recovery and resumed his scouting duties. Later, he often joked about his near-death experience.

Spud Chandler, who went to the hospital in Mobile with Clary, told this story about it: “’He motioned me over to his bed and whispered, ‘Spud, I want you to do something for me.’ I said, ‘Anything.’ He said, ‘I want you to go down and get the mileage off that ambulance so I can turn it in on my expense report.’ ”32 Clary later joked that he wanted to write a book titled “Death is Over-rated or Dying on Sunday Can Ruin Your Whole Weekend.”33

Clary was inducted into the Georgia Sports Hall of Fame in 1993.

Ellis Clary died of heart failure at age 83 on June 2, 2000, in his native Valdosta, shortly after his 60th wedding anniversary. He and Myra, who survived him by a year, are buried at Sunset Hill Cemetery there.

His humor often made it into his scouting reports. According to a Chicago Sun-Times article in 1989, Clary had this to say about Ryne Sandberg: “I found his weakness. He can’t slide into the wind.”34

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Jack Zerby and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Sources

In addition to the Sources cited in the Notes, the author used the Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org websites.

Notes

1 Richard Goldstein, “Ellis Clary, 85, Baseball Lifer Whose Tales Rivaled His Play,” New York Times, June 6, 2000: A23.

2 Bob Addie, “Bob Addie’s column,” The Sporting News, March 20, 1957: 14.

3 Clary’s Sunset Hill Cemetery headstone lists his birth year as 1914, but all other sources list it as 1916, which is consistent with him being 18 the year he graduated from Valdosta High School.

4 1930 U.S. Census, accessed through FamilySearch.org.

5 Bob Broeg, “Clary a Merry Man of Memory,” The Sporting News, May 7, 1977: 6.

6 Albert Riley Jr., “Thomasville upsets Valdosta, 13-0,” Thomasville (Georgia) Times-Enterprise, November 13, 1934: 8.

7 “Two A.L. Clubs Up to 40-player Limit, The Sporting News, November 18, 1937: 3.

8 Shirley Povich, “Hats Off,” The Sporting News, September 18, 1946: 14.

9 J.G. Taylor Spink, Paul A. Rickart and Joe Abramovich, Baseball Register, 1957 Edition (St. Louis: C.C. Spink & Son, 1958), 265.

10 Povich, “Capital Captivated by Capers of Clary,” The Sporting News, June 19, 1942: 11.

11 V.N. Wall, “Springfield Nats’ Youngster Fired for Dousing Hecklers,” The Sporting News, July 20, 1939: 2.

12 Spink.

13 Povich, “Ellis Clary Fought Cops and Pitchers,” The Sporting News, July 21, 1954: 12.

14 Povich, “Capital Captivated…”.

15 Frederick G. Lieb, “Home Town Finally Marks Christman Star,” The Sporting News, October 5, 1944: 9.

16 Broeg.

17 Valerie Vecchio, “Syracuse Chiefs Notebook,” Syracuse Post Standard, May 9, 1988: 21.

18 Goldstein.

19 “Training Camp Note,” The Sporting News, March 29, 1945: 13.

20 AP, “Oriole Manager Who Sent Clary After Heckler Is Cleared,” Washington Post, May 3, 1949: 15.

21 International League briefs, The Sporting News, June 22, 1949: 24.

22 “Clary Kicks Umps’ Door, Draws Fine and Suspension, The Sporting News, May 24, 1950: 35.

23 Southern Association briefs, The Sporting News, August 13, 1952: 29.

24 Hal Lebovitz, “Tribe-Senator Free-for-All Brings Wounds and Fines,” The Sporting News, May 13, 1959: 26.

25 South Atlantic League briefs, The Sporting News, July 26, 1961: 27.

26 Povich, “This Morning,” Washington Post, April 2, 1950: C1.

27 Oscar Ruhl, “From the Ruhl Book,” The Sporting News, December 5, 1956: 18.

28 Bob Addie, “Bob Addie’s Column,” Washington Post, July 28, 1956: 8.

29 Neal Russo, “Like Old Times in St. Louis” ’44 Browns, Cards Reunion,” The Sporting News, August 9, 1964: 11.

30 Associated Press, “Honors in St. Louis,” Indiana (Pennsylvania) Gazette, May 19, 1984: 25.

31 Mark Whicker, “Athletics are best, and so is AL West,” Orange County (California) Register, October 10, 1989: C2.

32 Goldstein.

33 Vecchio.

34 Dave van Dyck and Joe Goddard, “AL Bits,” Chicago Sun Times, July 2, 1989: 13.

Full Name

Ellis Clary

Born

September 11, 1916 at Valdosta, GA (USA)

Died

June 2, 2000 at Valdosta, GA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.