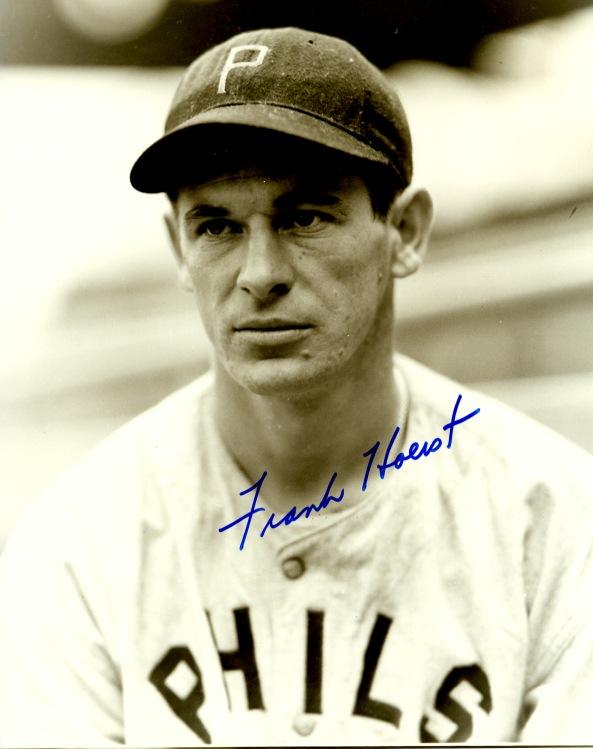

Lefty Hoerst

Frank “Lefty” Hoerst was one of Philadelphia’s best high-school and college basketball players of the 1930s at a time when there was no viable national basketball league. Upon graduating from LaSalle in 1939 he turned to his second best sport, baseball, and signed with the local Phillies. A year later, he debuted with the lowly cellar-dwellers after less than a full season in a Class-D League. Forced to pitch well before he was ready, Hoerst posted an unenviable 10-33 record in parts of five big-league seasons that were interrupted by a three-year stint serving on dangerous missions in the US Navy.

Frank “Lefty” Hoerst was one of Philadelphia’s best high-school and college basketball players of the 1930s at a time when there was no viable national basketball league. Upon graduating from LaSalle in 1939 he turned to his second best sport, baseball, and signed with the local Phillies. A year later, he debuted with the lowly cellar-dwellers after less than a full season in a Class-D League. Forced to pitch well before he was ready, Hoerst posted an unenviable 10-33 record in parts of five big-league seasons that were interrupted by a three-year stint serving on dangerous missions in the US Navy.

Frank Joseph Hoerst Jr. was born on August 11, 1917, in Philadelphia. His father, Frank Sr., the son of German immigrants, rose from a tank inspector at the shipyards to tax receiver at city hall. Mother Alice (Mallen) Hoerst was, like her husband, a native Pennsylvanian, and welcomed seven children into the world, born between about 1914 and 1926. Frank Jr., the third born, attended St. Anne’s Catholic elementary school, just a few blocks from where the family resided in the Olde Richmond neighborhood in the northeastern part of the city, close to the Delaware River. At Northeast Catholic High School, Frank was a standout athlete, earning letters in football, basketball, and baseball, as well as an excellent student. He graduated in 1935, and then attended LaSalle College, a small Catholic school in Philadelphia. Standing 6-feet-3, with long arms, the wiry Hoerst might have forsaken baseball had the NBA existed at the time. During his four years on the hardwood for the Explorers, he was a two-time captain and set a school record for most career points (556 in 71 games).1 In 1963 he was inducted into the LaSalle Hall of Athletes.2

An all-around athlete, Hoerst earned his reputation as a hard thrower on the baseball mound for a number of semipro and club teams during his college years. Pitching for the prestigious Pennsylvania Athletic Club, he made headlines by striking out all 10 batters he faced against Temple University on April 10, 1937.3 Three days later sportswriter James C. Isaminger called the teenager’s stuff “puzzling” in an exhibition game the Philadelphia Athletics at Shibe Park.4 Hoerst pitched for Port Richmond in the highly competitive Philadelphia League in 1937 and 1938 and in a summer league in Burlington, Vermont, in 1938.5

Upon graduation with a BA in business administration from LaSalle in the spring of 1939, Hoerst had offers from the New York Giants, Chicago White Sox and Phillies to begin a career in baseball. Unsure what he should do, he sought counsel from his former North Catholic baseball coach, Jocko Collins, who at the time was working for the post office. “I thought he’d be better off with the Phillies,” said Collins, “so I took him in to see (club owner) Gerry Nugent and he signed him.”6 Collins benefited, too; Nugent offered him a job as scout, a position he held into the 1960s. Hoerst was assigned to the Mayodan (North Carolina) Millers in the eight-team Bi-State League, one of 21 Class-D minor leagues. Though his 8-9 record did not raise eyebrows, Hoerst paced the short-season circuit in ERA (2.82 in 153 innings) despite issuing 100 walks. He was named to the North Carolina squad in the league’s second annual all-star game against the Virginia all-stars.

Back home in Philadelphia in the offseason, Hoerst served as assistant basketball coach at his high-school alma mater and played semipro basketball for the Schuylkill Havens in the Tri-County League. After the Phillies announced that he would be assigned to the Class-B Pensacola Pilots of the Southeastern League, they had second thoughts. Instead, they added him to their 40-man roster and invited him to spring training in Miami in 1940.

Described by Philadelphia sportswriter Cy Peterman as “the butt of the National League, pushover for several years,” the Phillies were a cash-strapped team in disarray.7 Coming off a dreadful season (45-106) in 1939, the club had posted only one winning season since it traded future Hall of Fame hurler Pete Alexander after the 1917 season. Skipper Doc Prothro hoped the 22-year-old, inexperienced Hoerst, praised by the Philadelphia Inquirer for his “speed,” might help a staff whose team ERA (5.17) was the highest in the league.8 The local-kid-made-good jumped from D-ball to the big leagues when he debuted on April 26 by tossing two scoreless innings of relief, allowing a hit and walking three, in a 6-0 loss to the Brooklyn Dodgers at Shibe Park. Hammered in his subsequent outings, but also securing his first victory in three rocky innings of relief against the Pittsburgh Pirates on May 20, Hoerst was optioned at the end of May to Pensacola, where his 16-7 record and 2.56 ERA helped lead the Pilots to the league title.

Despite another last-place finish (50-103) and again the worst staff ERA in the league (4.40) in 1940, skipper Prothro looked forward to the 1941 campaign. “I have the best young pitching staff in the major leagues,” he said confidently, pointing to Hoerst, 21-year-olds Johnny Podgajny and Tommy Hughes, and 24-year-old Ike Pearson. With no other viable left-handed starter expected in camp, much was expected of Hoerst; however, less than 10 days before departing for Miami, he broke his left ankle while coaching high-school basketball.9 The inopportune injury also reflected his nickname – Ruff, which he had acquired for his physical play on the hardwood, and could not have come at a worse time. With his foot in a cast, Hoerst was sidelined for six weeks, missed all of camp, and was not in baseball shape when he debuted on May 7, yielding two runs in three innings of relief against the Cubs. By the end of the month he was 0-3 (with losses in his first two starts) and had a 6.91 ERA while the Phillies were already 18½ games behind the league-leading St. Louis Cardinals. Teetering on financial insolvency, the Phillies had finished last in the NL in attendance every year since 1931, and averaged just over 3,000 fans per game in ’41. “There was been no attendance to speak about,” quipped Cy Peterman in the Inquirer about the sad state of affairs. “[H]ence there’s no surplus cash with which to build. The sale of players has run its course, destroying public loyalty over the years. … The club is now stuck with minor leaguers.”10 Hoerst was no doubt one of the “minor leaguers” Peterson identified. After limiting the Cincinnati Reds to just five hits and two runs over eight innings in a tough-luck loss in the first game of a doubleheader on August 20 to drop his record to 0-6, Hoerst picked up his first win of the season four days later by recording the final out in the ninth in the second game of a doubleheader against the Cubs before the Phillies won in walk-off fashion. Hoerst finally put it all together in the second game of a twin bill against the Dodgers on September 3, tossing what sportswriter Stan Baumgartner called the “greatest game of his career,” a complete-game four-hitter to defeat the eventual pennant winners, 4-1, at Shibe Park. The Phillies lost a team-record 111 games and finished last in the NL in almost every meaningful offensive category, as well as team ERA (4.50). Hoerst (3-10) started in 11 of his 37 games; his 5.20 ERA (in 105⅔ innings) was the NL’s second highest among pitchers with at least 100 innings. As Prothro had predicted, Hoerst joined the staff’s other young hurlers, Podgajny (9-12), Hughes (9-14), and Pearson (4-14), in a baptism of fire.

In the offseason, Hoerst was victorious again when he married Florence Gallagher of Philadelphia on January 24 at St. Anne’s Catholic Church. They had two children, Judith and Frank Joseph III.

One might wonder if Hoerst wished that offseason rumors of his trade to the Dodgers were true. Team owner Nugent, on the verge of economic collapse, needed a cash infusion from the NL just to meet basic expenses for spring training in 1942 for new skipper Hans Lobert.11 Hoerst, derided by sportswriter Frank Simmons for “not [being] in condition” and well above his normal weight of about 190 pounds, pitched sparingly and poorly in camp.12 “The Phils are likely to lose a lot of ball games,” wrote Simmons in what was probably the understatement of the year. In fact, the Phillies lost two fewer games than in the previous season, but also played three fewer to finish with a franchise-worst .278 winning percentage. Hoerst shucked off his struggles to hold the Dodgers to two runs in seven strong innings, but picked up the loss, 7-1, in his debut on April 17 at Ebbets Field. Described by the Inquirer as “hard medicine for the Dodgers to swallow,” Hoerst fired a five-hitter in his next outing, also against the Dodgers, to beat them, 4-2, at the home opener at Shibe Park, on April 24.13 “[Hoerst] isn’t highly regarded around the league,” opined sportswriter Tommy Holmes in the Brooklyn Eagle, but he noted nonetheless that he had turned into a “first-rate jinx” for Dem Bums.14 Hoerst improved his record to 3-2 with a six-hitter against the Cardinals on May 12 and was suddenly the newest sports darling in the City of Brotherly Love and a veritable “ace” (according to Stan Baumgartner).15 “From out of nowhere, the Phils are developing worthy pitchers,” gushed Cy Peterman, even though the club got off to a major-league-worst 8-23 start. He praised Hoerst for “his terrific fast one, a swooshy curve and the start of a snazzy change-of-pace.”16 And then the bottom fell out for Hoerst. He lost his next eight decisions and 14 of 15, a streak of misery interrupted only by his route-going 10-hit, 6-1 victory over the Cubs in the second game of a doubleheader on July 26. Hoerst’s season came to a conclusion about three weeks prematurely. With World War II waging, Uncle Sam began to call professional ballplayers to the services. Classified 1-A (fit for service) in early June, Hoerst was called up by the Navy in early September. On his last day in a Phillies uniform for more than three years, the southpaw was feted on “Frank Hoerst Day” at Shibe Park on September 6. In between games of a twin bill, Hoerst received a fountain pen from teammates and a watch from Nugent, then pitched “magnificently” (gushed Baumgartner in the Inquirer) through six innings, only to surrender five runs in the seventh to pick up the loss, 7-3.17 Hoerst’s final slate was unenviable: a 4-16 record was accompanied by the league’s highest ERA for any pitcher with at least 100 innings (5.20 in 150⅔ innings). Nonetheless, Hoerst formed with Hughes (12-18), Rube Melton (9-20), Si Johnson (8-19), and Podganjy (6-14) the core of the Phillies staff.

“[Hoerst] should have been a great pitcher,” pronounced Baumgartner harshly in the Inquirer, “[but] was a bust.” However, the longtime Philadelphia scribe didn’t blame Hoerst for his shortcomings; rather, he looked at the greater context of the war and how it affected each player in baseball. “Ordinarily a keen student of the game, intensely interested in hitters, their weaknesses and their strength, [Hoerst] would bend your ear about baseball,” he wrote. “Last year, before going into the service, he talked of nothing except the [service].”18

Over the next three years, Hoerst had little time to think about, let alone play, baseball. He was mustered in soon after Frank Hoerst Day, spent seven weeks in basic training, and was then thrust into combat. According to Gary Bedingfield’s excellent and thorough site “Baseball in Wartime,” Ensign Hoerst served on a number of ships, including on the Queen Elizabeth as part of an armed convoy through treacherous waters of the North Atlantic to deliver supplies to Murmansk, the Soviet port in the Arctic.19 “In the afternoon the bombers came and at night the subs,” recalled Hoerst. “We saw torpedo tracks fore and aft and we passed through mines on each side. We were lucky to not be hit.”20 Seven of the 30 ships in his convoy weren’t so lucky and were sunk. Hoerst subsequently served on ships that traveled throughout the Atlantic and later in the Pacific. He was a gunnery officer on the USS Sappho, an attack cargo ship, which was part of the fleet that dropped the first marines at Sasebo, located about 60 miles northwest of Nagasaki. “Our unit,” said Hoerst, “was trying to come into Japan from the north, rather than make a frontal attack on the islands. [A]fter getting a look at the magnificent natural defenses of the mountain-locked harbors of the main Japanese cities, we can be thankful for the atomic bomb.”21 [The United States dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima on August 6 and Nagasaki on August 9, 1945]. Hoerst returned home to Philadelphia in late November 1945 on terminal leave and was formally discharged on January 10, 1946, with the rank of lieutenant.

Genuinely well-liked by teammates and fans, Hoerst rejoined the Phillies at spring training in 1946 in Miami. The three previous seasons had not been kind the club. Nugent had sold the team to lumber baron William D. Cox before the 1943 season. By midseason, rumors swirled that Cox had placed bets on his own club. Commissioner Kenesaw Landis ultimately intervened and forced Cox to sell the club, and subsequently banned him from baseball for life. Robert R.M. Carpenter, the heir to the DuPont fortune, bought the club, but even with his deep pockets, the club still finished in last place in 1944 and 1945. In 1946 few prognosticators expected the Phillies to improve on their 46-108 record from the previous season given that major-league rosters were refilled with veterans returning from the services.

A productive spring landed Hoerst a berth in the rotation for skipper Ben Chapman’s Phillies, whom the press still occasionally called the Blue Jays, a remnant of Cox’s ill-fated attempt to rebrand and rename, at least informally, the perennial cellar-dwellers. Hoerst yielded only three hits in 6⅓ innings in his debut against the New York Giants at the Polo Grounds on April 17; however, he also walked nine, leading to all the runs in a 5-2 loss. After another loss in his next outing (three runs in two frames against the Dodgers at Shibe Park), Hoerst was shunted to the bullpen. Save for a complete-game six-hit, 2-1 victory against the reigning NL-pennant wining Cubs on July 26 in front of more than 24,000 spectators in Philadelphia, the season was personally trying for Hoerst. He made only 18 appearances (seven starts) and compiled a dismal 1-6 record with a 4.61 ERA in 68⅓ innings. The Phillies, on the other hand, enjoyed their best campaign since their last wining season, in 1933, and finished in fifth place (69-85).

Time slipped by Hoerst in 1947, as the effects of losing three years to the war and having pitched fewer than 700 innings in his professional career finally caught up with him. He came down with arm pain during spring training, a piece of misfortune that further reduced his already slim chances of making the club. Chapman counted on two southpaws, Ken Raffensberger (later traded in June) and 39-year-old Oscar Judd, and a duo of right-handed graybeards, Dutch Leonard and Schoolboy Rowe, as well as Tommy Hughes as his starters. Hoerst was consequently optioned to Double-A Memphis in the Southern Association. Reunited with skipper Doc Prothro, Hoerst won a team-high 12 contests for the Chicks, who finished in seventh place in an eight-team league. Recalled by the Phillies in September, Hoerst spent his final three weeks in a big-league uniform. He was clobbered in his first outing, yielding nine hits and all seven runs (five earned) in what proved to be his final start in the majors, a 7-3 loss to the Cubs on September 13. In a career that was seemingly defined by bad news and losses on the field, Hoerst’s final day on the mound was a type of redemption and somehow fitting, if not well deserved. In the first game of a doubleheader against the Giants at the Polo Grounds, he tossed 1⅔ innings of scoreless relief and was credited with the victory, 3-2, in 11 innings. Hoerst took the mound again in the second game, and tossed 2⅔ more innings of scoreless relief in a 4-6 loss.

After several weeks of spring training in 1948, Hoerst’s tenure with the Phillies came to an official close on April 1, when the club sold him outright to Memphis.22 A 5-10 slate and 4.78 ERA in 113 innings probably suggested to Hoerst that it was time to put his college education to work. After seven seasons in Organized Baseball, Hoerst hung up his spikes. In parts of five seasons in the majors, he won 10 and lost 33 with a 5.17 ERA in 348 innings spread over 98 appearances, including 41 starts. He compiled a 41-37 record in the minors.

Unlike many players of his generation and earlier, Hoerst was well-situated and well-connected to start a productive post-baseball career. He had remained close to his alma mater, LaSalle College, since graduating. He had coached the freshman basketball squad in 1946-47 and was a visible presence in the athletic programs. From 1953 to 1957 he served as the head baseball coach, compiling a 44-34-1 record over five seasons. In the fall and winter he was a referee in the nascent National Basketball Association.23 His business career took off in 1957 after he resigned from his baseball and basketball duties to work for Gretz Brewery in Philadelphia. He rose from sales manager to vice president. He later worked in the vermiculite industry (a material resembling mica that is used in construction and gardening) before founding his own company, Vermiculite LTD in 1980. He retired in 1990.

Frank “Lefty” Hoerst died at the age of 82 on February 18, 2000, at the Rosewood Nursing Home in Maple Shade, New Jersey. He was survived by his second wife, Helen Larkin Meehan Hoerst, his two children from his first marriage, and three stepchildren. He was buried at the Holy Sepulcher Cemetery in Cheltenham, Pennsylvania.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also accessed Hoerst’s player file and player questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, Bill Lee’s The Baseball Necrology, the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com, The Sporting News archive via Paper of Record, and Ancestry.com.

Notes

1 La Salle College Basketball Handbook, 1961-1962, 9. http://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1004&context=basketball_media_guides.

2 LaSalle Explorers Hall of Athletes. http://goexplorers.com/hof.aspx?hof=7&path=&kiosk=.

3 Frank Byrod, “Frank Hoerst Hurls Pennac Tossers to 9-4 Triumph over Temple, Philadelphia Inquirer, April 11, 1937: 20.

4 James C. Isaminger, “Athletics Level Pennacs, 9-3,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 14, 1937: 19.

5 Associated Press, “Phils Get Frank Hoerst,” Morning News (Wilmington, Delaware), February 13, 1940: 16.

6 John Dell, “Baseball Opportunity Still Knocks,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 13, 1962: 41.

7 Cy Peterman, “Phil Rookie and $50 Thousand Might Ease Doc’s Pain,” Philadelphia Inquirer, March 13, 1940: 29.

8 Ibid.

9 Perry Lewis, “Phils’ Hoerst Breaks Ankle,” Philadelphia Inquirer, February 20, 1941: 25.

10 Cy Peterman, “Phils Sabotaging Selves, But It’s Not Intentional,” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 14, 1941: 19.

11 “1942-43 Phillies: Turmoil, Scandal, Hope,” The Good Phight, SB Nation. http://thegoodphight.com/2015/12/7/9834750/1942-43-phillies-turmoil-hope-and-what-might-have-been.

12 Frank Simmons, “Browns Shade Phils in 10 Innings, 8 to 6,” Philadelphia Inquirer, March 30, 1943: 33.

13 “Phils Drop 4th Straight,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 18, 1942: 21.

14 Tommy Holmes, “Hoerst Throws Leo’s K-79 Play for a Loss,” Brooklyn Eagle, May 25, 1942: 9.

15 Stan Baumgartner, “Pirates Here to Battle Phils,” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 17, 1942: 34.

16 Cy Peterman, “Phils Garden of Pitchers Now Presents Frank Hoerst,” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 18, 1942: 27.

17 Stan Baumgartner, “Phils Lose 2 on Hoerst Day,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 7, 1942: 23.

18 Ibid.

19 Gary Bedingfield, “Lefty Hoerst,” Baseball in Wartime. http://baseballinwartime.com/player_biographies/hoerst_lefty.htm.

20 Ed Pollock,” Playing the Game.” [unnamed paper, dated May 24, 1953]

21 Stan Baumgartner, “Hoerst Returns; Waits Discharge,” Philadelphia Inquirer, November 30, 1945: 45.

22 “Chicks Buy Hoerst,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 2, 1948: 34.

23 “Jim Pollard Will Attend Sallie Fete,” News-Journal (Wilmington, Delaware), February 27, 1957: 26.

Full Name

Frank Joseph Hoerst

Born

August 11, 1917 at Philadelphia, PA (USA)

Died

February 18, 2000 at Maple Shade, NJ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.