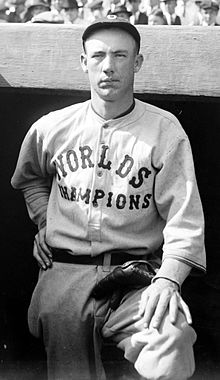

Guy Morton

Guy Morton reported to New Orleans for spring training in 1914 with Cleveland. After a few workouts his manager, Joe Birmingham, was unimpressed. “He doesn’t know how to stand on the rubber even. He doesn’t know how to hold the ball.” What he did have was a tremendous fastball and Birmingham declared, “[O]nly one pitcher in the country has more speed and that is one Walter Johnson.”1 Birmingham entrusted Morton to minor-league manager Lee Fohl to turn him into a pitcher instead of a thrower. With Fohl’s guidance, Morton went on to pitch 317 games over 11 seasons with Cleveland.

Guy Morton reported to New Orleans for spring training in 1914 with Cleveland. After a few workouts his manager, Joe Birmingham, was unimpressed. “He doesn’t know how to stand on the rubber even. He doesn’t know how to hold the ball.” What he did have was a tremendous fastball and Birmingham declared, “[O]nly one pitcher in the country has more speed and that is one Walter Johnson.”1 Birmingham entrusted Morton to minor-league manager Lee Fohl to turn him into a pitcher instead of a thrower. With Fohl’s guidance, Morton went on to pitch 317 games over 11 seasons with Cleveland.

Morton hailed from Vernon, Alabama, a small town almost on the border with Mississippi. Born on June 1, 1893, he was the youngest of 12 children born to Dr. Martin W. Morton and Mary (Nelson) Morton. Dr. Morton was a second-generation country doctor who died just four days after Guy’s birth.2 The Mortons were a close-knit Scotch-Irish family; in 1900 Mary was keeping house for 10 of the children plus two grandchildren. Income was provided by two daughters who were teachers and four sons who worked as laborers. Morton attended school in Vernon through the ninth grade.

Little is known of Morton’s early baseball life. Most certainly he played with his siblings and with the other children in town. At least one of his brothers had great interest and knowledge about baseball. In 1913, he was a Cotton States League umpire and even worked in games played by Guy’s Columbus, Mississippi, team.3 To date no box scores have been located that have Guy pitching when his brother was the umpire. As for Guy’s development, popular legend has him wandering the woods and throwing stones at trees. When trees proved too easy, he turned his attention to squirrels.4 The legend continued that Morton walked into town with a string of squirrels he had killed. In the course of conversation, he mentioned he was a “pegger.” The local team suited him up and had him pitch batting practice. “Much to the surprise of everyone, the stranger whizzed his fastball past them and had them standing on their heads.”5

The 1913 Cotton States League was a six-team Class D aggregation that opened on April 10 with plans for a 110-game season. The league shut down on July 27, with teams having played around 95 games, because of financial issues. Morton joined the Columbus Joy Riders and made his first appearance on June 17 versus Clarksdale. With a 15-4 lead, manager Bob Kennedy felt safe seeing what the youngster could do. Kennedy liked the results and Morton got his first start on June 21 in Jackson. He struck out 12, but lost 5-1. Next he took on first-place Pensacola and beat them 3-2, again striking out 12. A newspaper writer described Morton as “a boy from the country, (who) knew little of the finer points of the game, but had a curve and speed that could not be fathomed.”6 Morton ended the campaign with a 5-5 record. Scout Bobby Gilks heard of Morton’s talent and recommended him to Cleveland.

Joe Birmingham was entering his second full season as manager of Cleveland in 1914. He had led the team to 86 wins the previous season. He was on the lookout for pitching because Cy Falkenberg (23 wins) had defected to the Federal League and Vean Gregg (20 wins) had arm problems. Birmingham thought that Morton might have success against Eastern Association batters and entrusted his development to manager Lee Fohl at Waterbury.

Fohl began teaching Morton the finer points of the pitching trade. Morton was an apt student. Fohl proclaimed, “[S]how him once how to do something and he masters it. I never saw a boy learn as rapidly as him.”7 They soon realized that Morton’s leg kick was related to control issues. With practice the twosome found the right level of kick to keep Morton balanced. Fohl had an advantage over other managers with a pitcher in development because he was also the number-one catcher on the Class B Waterbury Contenders.

Morton took the Eastern Association by storm. Birmingham was correct: Morton’s heat and curve were too much for the hitters. The Contenders were two games behind New Britain in the pennant race when Morton was sent back to Cleveland. He had posted an 8-1 record. His only loss was to New Britain in 11 innings. He later beat New Britain on a one-hitter. He struck out 19 in a matchup with Springfield. One league newspaper credited him with 131 strikeouts in 98 innings.8His final appearance was a masterful no-hitter against New Haven on June 16.

Morton was under contract to Waterbury. After his stellar beginning, the Brooklyn Dodgers took great interest and had a scout following the team. The Dodgers’ interest, raids for talent by the Federal League and court cases concerning contracts led Fohl to suggest that Cleveland should get Morton under major-league contract as soon as possible. Guy was sent to Cleveland on June 17, signed and made his first appearance on June 20.9

The Naps had struggled and sat in last place with an 18-35 record when Morton reported. His initial outing, versus the Yankees, went well. He allowed two hits and a run in three relief innings. He continued to pitch in relief, then got a start on July 13 in Boston. He tossed a complete game, losing 2-0. He joined the rotation for a month and then was a spot starter/reliever the rest of the season. Hard luck dogged Morton and his record was 0-13 before he finally earned a complete game victory, 5-3, over New York on September 27. Despite the lackluster winning percentage, he led the team in WHIP and in strikeouts-to-walks ratio.

Cleveland got off to a 12-18 start in 1915 and manager Birmingham was fired on May 22. He was replaced by Fohl, who had joined the team as a coach. After 51 wins in 1914, Cleveland amassed 57 victories in 1915 and avoided last place. Morton was one of the few glimmers of hope that season. The team’s winning percentage was .375. Morton went 16-15 for a .516 percentage. He was the star of the team and figured in Birmingham’s firing. Birmingham had announced that Morton would pitch on a Saturday. Then he changed his mind. The fans and newspaper writers were greatly displeased and owner Charley Somers cut Birmingham loose.

Morton led the 1915 Indians in wins, ERA, complete games, shutouts, innings pitched, WHIP, and strikeouts-to-walks ratio. His six shutouts were one behind Jim Scott of Chicago and Walter Johnson for the league lead. In both WHIP and K/BB ratio, he placed third in the league. While the Cleveland franchise suffered in 1914-15, they made moves that would strengthen them for the future. Jim Bagby and Stan Coveleski were discovered in the minors and would join the team in 1916. Pitcher Sam Jones was swapped in a package to Boston for Tris Speaker. Morton was in position to be an integral part of the Tribe’s rebuilding.

Morton followed up his 1915 campaign with a fast start in 1916. As in Waterbury, he got off to an 8-1 start. Then the arm started to bother him. He went 10 days between starts and then laid off for 15 more. After one inning on June 27 he was shelved until August. The injury did nothing to diminish Morton’s popularity with the fans. The tall (6-feet-2),10 lanky right-hander was announced as the starter for August 6 versus the Athletics at Dunn Field. A crowd of 15,000 turned out to witness his victorious return with a 5-2 win.

Morton struggled the remainder of the season, then served as a starter and reliever in 1917. He did turn in the highlight performance of the season for Cleveland when he hurled a one-hitter against the Boston Red Sox. Babe Ruth broke up the no-hit bid with a single in the eighth. Dubbed the Alabama Blossom, Morton returned to the rotation in 1918 and had a season very similar to 1915. He hurled a one-hitter again at the Red Sox; this time Amos Strunk did the damage with a Texas Leaguer. Because of the World War, the major leagues shut down early and shortly thereafter, Morton received his draft notice.

Drafted into the Army, Morton was stationed at Camp Pike, near Little Rock, Arkansas. There he was joined by major leaguers Muddy Ruel, Benny Karr, Ray Schmandt, and Bill Fincher. Morton helped to organize a camp baseball team and they defeated nearby Army camps. He was recommended for officer’s training camp, but the war ended before he could finish training. He wrote manager Fohl that Army life agreed with him. He put on 10 pounds of muscle and felt that he had filled out. He even suggested, “I’ll be able to go in and pitch a double-header and win it. …”11

Unfortunately for Morton, a bout with flu just before training camp opened in 1919 caused a weight loss and he spent the spring regaining his strength. He went north in fine shape and opened the season with back-to-back shutouts over the St. Louis Browns and Detroit Tigers. He was in the rotation until the end of July, when once again the arm forced him to shut down. He made only five appearances after July 29.

In 1920, Morton was the fourth starter until the arrival of Duster Mails. The Indians finally went into first place to stay on September 17 and held on for a two-game lead over the Chicago White Sox. Morton was not called upon for any action in the World Series victory over the Dodgers. In 1921, he made only seven starts in his 30 appearances. He returned to the rotation in 1922 when he posted a 14-9 record, but was back into his part-time starter role for 1923. He struggled as a reliever in 1924.

In mid-June 1924, Morton was sold to the Kansas City Blues of the American Association. He closed out his major-league career with a 98-86 record and a 3.13 ERA. The Blues sold him to the Indianapolis Indians on August 16. With the two franchises, he appeared in 27 games and posted a 5-6 record.12He spent the following five seasons in the Southern Association with Memphis, Mobile, and finally Birmingham. He closed out his career with two seasons at High Point in the Class C Piedmont League. As a final hurrah, at age 38 Morton was the only High Point player named to the Piedmont League all-star team.13

Morton married Edna McDaniel on March 13, 1919, in Birmingham, Alabama. Their only child, Guy “Moose” Morton Jr., a catcher who played in one game for the Red Sox in 1954, was born on November 4, 1930, in Tuscaloosa, Alabama.

When Morton’s career ended, the family settled in Sheffield, Alabama, which is across the Tennessee River from Florence, Alabama. As part of the Tennessee Valley Authority system, the river had been dammed near there to create Wilson Lake. Morton was hired as a worker at the Wilson Lake Dam. He pitched semipro baseball for Florence in 1932 and 1933. He played on the TVA team in 1934. Morton had little time to teach his son the game he loved because he died from a massive heart attack on October 18, 1934. His burial was held in his hometown of Vernon at the Vernon City Cemetery. He was inducted into the Alabama Sports Hall of Fame in 2002.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Len Levin and fact-checked by Alan Cohen.

Notes

1 Henry P. Edwards, “Morton Makes Rapid Strides in Space of Two Brief Campaigns,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, June 25, 1916: 21.

2 George Thompson Morton family tree at http://ancestry.com/familytree/person/tree/24708820/person/1572316205/story.

3 “Columbus Wins a Comedy,” Times-Picayune (New Orleans), July 22, 1913: 10.

4 Norman E. Brown, “Fate Toys Long with Guy Morton Before Consigning Him to Baseball Oblivion,” Canton (Ohio) Repository, July 1, 1924: 15.

5 Robert W. Maxwell, “Big League Scout Now Active Combing South for Recruits,” Philadelphia Evening Public Ledger, April 11, 1919: 27.

6 “Merritt Allows Jackson But Two Hits,” Montgomery Advertiser, June 29, 1913: 15.

7 Edwards.

8 Hartford Courant, June 17, 1914: 17.

9 Ibid.

10 Morton is listed at 6-feet-2 and 165 pounds on his HOF questionnaire. Contemporary newspapers use both 6-feet-1 and 6-feet-2.

11 “Morton Likes Army Life,” Columbus (Georgia) Daily Enquirer, November 12, 1918: 2.

12 Reach Official American League Base Ball Guide for 1925 (Philadelphia: A.J. Reach Company, 1925), 290.

13 “Piedmont All-Star,” Greensboro Record, August 17, 1931: 10.

Full Name

Guy Morton

Born

June 1, 1893 at Vernon, AL (USA)

Died

October 18, 1934 at Sheffield, AL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.