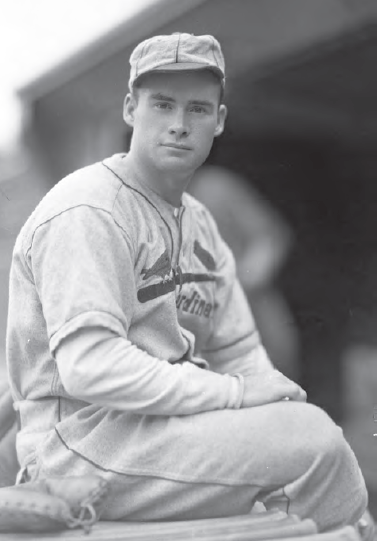

Francis Healy

Over the years, there has been no shortage of adjectives to describe the 1934 St. Louis Cardinals. Raucous, rambunctious, and rowdy have been just a few of the terms used to portray the Deans, Durochers, Martins, and Medwicks of the club. Yet not everyone on the team fit the public’s perception of this hell-raising, pennant-winning contingent. For instance, Francis Healy, the bullpen and reserve catcher, was by all accounts quiet and a devout Catholic. His demeanor was such that Dizzy Dean came to call him “Father” Healy.

Francis Paul Healy was born on July 29, 1910, in Holyoke, Massachusetts to Catherine and Jeremiah Healy, the fifth of seven children. 1 His parents had come from Ireland around the turn of the century and married a few years later; some sources say in 1902. Jeremiah worked for the city.

Healy reminisced that as a child he spent a great deal of time on the playground watching the older boys play, and eventually was asked to join in their games. Early on, he showed athletic potential playing baseball and football. 2 Healy went to school in the local parochial system, eventually attending St. Jerome High School.

There Smiling Mickey Welch, a resident of Holyoke and a former major league pitcher who was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1973, spotted Healy, Welch’s 307 major-league victories came predominantly with the New York Giants, and he maintained a strong affinity for the Giants and a good relationship with manager John McGraw. So when Welch sized up Healy’s potential as a player during the summer of 1929, he contacted the Giants skipper.

McGraw thought he saw in Healy the same potential he had seen five years earlier in Mel Ott. Like Ott, Healy was to be kept with the Giants so that McGraw could personally coach him in the ways of the game, not wishing to risk his being ruined through inadequate or incorrect tutelage on a minor-league team. That path had worked for Ott. McGraw was supremely confident it would work for Healy who, McGraw observed, had “natural abilities” and was “the find of the year.” He went on to describe Healy’s talents in effusive terms.3

While McGraw’s comments were impressive, he often described newcomers similarly. Several years earlier, he spoke of a rookie named Fay Thomas as having “more stuff than any young pitcher I have seen since Mathewson.” He touted Jimmy Ring, obtained in a trade, as “one of the best pitchers in the League and a glutton for work.” Neither pitcher left much of an impression on Giants fans.4

Healy joined the Giants for spring training in 1930 having never played ball beyond local contests in Holyoke. He was out of his element. While his talent was a potential, his naïveté was a certainty. The same article that spoke of his ability described him as “a green, freckled faced boy, the most gullible in the camp. He’s a sucker for a pail of steam, and if you tell him to fetch a left-handed bat, he’ll go look for it.” Tom Clarke, a Giants coach, took Healy under his guidance, sharing a room and arranging for them to eat their meals together. Of Healy, Clarke observed, “Healy is young and hasn’t been around much.” 5

Healy stayed with the Giants through the first few months of 1930 until he was sent to the Bridgeport Bears in the Class A Eastern League. Appearing in 31 games, he hit .269 before returning to the Giants for a single pinch-running appearance during the last week of the season. For the year, Healy appeared in seven games, mostly as a pinch-runner. He had two unsuccessful at-bats pinch-hitting.6

In 1931 Healy stayed with the Giants the entire year, appearing in six games and getting one hit in seven at-bats, his first major-league hit. He collected that hit the last week of the season, a single in a 15-7 slugfest victory over the Chicago Cubs at Wrigley Field. Healy also had two passed balls after replacing Bob O’Farrell in the fifth inning

Healy’s quest to crack into the Giants’ starting lineup was stymied because there were two accomplished receivers ahead of him. Shanty Hogan, a solid .300 hitter, and backup O’Farrell, then a 16-year veteran, had ability as well as experience that a young man off the sandlots of Holyoke with just and a handful of minor-league games could not come close to matching.

McGraw, who had championed Healy’s abilities, was not the same man who had adroitly transformed Ott five years before from raw rookie to accomplished outfielder. He was frequently ill and absent from the club, and his hold on the Giants by the end of 1931 had become tenuous. 7 In early June 1932, McGraw resigned and was succeeded by first baseman Bill Terry.

By then Healy was in the minors. He was assigned to the Double-A Columbus Red Birds after a single appearance with the Giants in late April. There, under manager Billy Southworth, Healy hit .347 in 44 games. They were the most games he had played in during any professional season. Although the Red Birds were a Cardinals affiliate, there is no record of Healy being dealt to them by the Giants.

The Giants recalled Healy in early September. After three seasons of almost total nonuse, the Giants decided to test his potential. He appeared in 13 games, catching in 11 and batting .250.

How Healy stood with the Giants organization became quickly obvious. Before the 1933 season they let Hogan go to the Boston Braves and traded O’Farrell to the Cardinals. In the latter transaction, receiver Gus Mancuso came to the Giants. Youngsters Harry Danning and Paul Richards joined the team to back up Mancuso. Healy went to the minors, splitting time between Columbus and Toledo in the American Association and hitting .272 for the season in 73 games. Mancuso, then Danning eventually became the Giants’ main receivers for the rest of the decade. Healy was expendable.

St. Louis, familiar with Healy’s ability through his play at Columbus, purchased his contract from the Giants on May 5, 1934. To make room for Healy on the roster, the Cardinals released 40-year-old Burleigh Grimes, the last major-league spitball pitcher. Grimes had pitched in the majors in 1933 and had hoped to stick with St. Louis, but Healy’s purchase made him odd man out.8

Healy’s role with the Cardinals was to serve as a utilityman and bullpen catcher. During the season he played in 15 games as a catcher, third baseman, or outfielder, pinch-hitter or pinch-runner, hitting .308 in 13 at-bats. None of his appearances proved consequential. He did not play in the World Series against the Detroit Tigers; but got a Series share worth $5,306 for being on the world champion Cardinals’ roster.9 The season was his last in the major leagues. Healy appeared in 42 games over four seasons with the Giants and Cardinals, hitting .241 with three doubles. He caught in only 18 of his 42 games; in the rest he was mostly a pinch-hitter or pinch-runner.

In 1935 Healy was assigned to the Rochester Red Wings in the Double-A International League. There he played in 61 games and hit .271. In 1936 he was sent down to the Columbus (Georgia) Red Birds in the Class B South Atlantic League, where he hit .316 in 122 games, the most games he played in during a season. His play drew favorable attention. The July 30 issue of The Sporting News ran an article about a poll among Columbus fans on who they though would be the most likely Red Bird to reach the big leagues. Healy was among those mentioned. It was not to be. He played a handful of games in 1937 and finished his career with the Houston Buffaloes of the Texas League in 1938 alongside fellow catcher Walker Cooper, who was two years away from his debut with the Cardinals. Healy hit .269 in his final year. He was 28 and his professional career was over. That same year also marked the end of an abbreviated career for his younger brother, Bernie, who made appearances for the Cambridge (Maryland) Cardinals of the Class D Eastern Shore League.

After leaving professional baseball, Francis Healy was virtually forgotten, but he was remembered in the early 1970s when his nephew Fran, Bernie’s son, caught for the Kansas City Royals, San Francisco Giants, and New York Yankees.

Some references in Francis Healy’s Hall of Fame player file indicate he had been ill for a number of years after his professional career had ended. An article in the Springfield (Massachusetts) Union-News & Sunday Republican after his death said that after being “shuffled off to the minors … (i)t was then, with the advice and consent of his brother Bernie, that he finally gave up the game and came home to Holyoke.”10 Whether this advice was triggered by the onset of Healy’s illness is subject to conjecture, but it appears Healy was incapacitated for several years.11 Healy alluded to illness himself in describing the end of his career: “The Cards shipped me to Houston and soon afterwards I was taken ill, ending my career.”12

Healy went to work for the local Department of Public Works in the mid-1940s and was employed for about 25 years before retiring in 1971. He lived quietly with a brother and sister in an apartment in Holyoke. Never married and highly religious, he belonged to the Passionist Retreat League and was a communicant of Holy Cross Church. He did not own a car and stayed close to home except when his brother Bernie took him to see young Fran play for the Royals in Boston or New York.

Described as a reticent conversationalist by his interviewer, Healy opened up when the subject was baseball. Of his years with the Giants, Healy recalled that while the Chicago Cubs were interested in him, he signed with the Giants on the advice of his father. Healy said he had pleasant experiences with most of those he came into contact with, although for a while he was mad at Bill Terry for shipping him off to the Cardinals until “I learned that Branch Rickey had arranged a deal to get me.”13

Despite competing with Shanty Hogan for the catcher’s job, Healy considered the fellow Irishman his best friend on the Giants. “We liked to eat out together, going to restaurants where they served corned beef and cabbage,” he said. “(Hogan) helped me tremendously, how to work back of the plate.”

Healy had the experience of catching two of the game’s pitching greats of the era, Dizzy Dean and Carl Hubbell. Comparing them, he said, “I believe Hubbell was a better pitcher. Further, I always felt Dizzy Dean’s side-arm pitch was faster than Diz threw. But I also felt Wild Bill Hallahan was faster than either one.”

Of the Gas House Gang, he recalled their wild behavior:

“Sure, they were a fun-loving and hell-raising group but not as bad as they have been painted. Dizzy Dean was more or less the ringleader. I vividly recall being in a Boston hotel and Dizzy, from his fourth-floor window, poured a pitcher of water on Frank Frisch, then manager, and Leo Durocher who were standing in front of the hotel. Honestly, I never saw a fistfight between two of the players on this club.

“Diz was forever cutting up and it was always in pure fun. There wasn’t a dull moment all the time we were together. It was sure great to play baseball with the Deans, Pepper Martin, Bill DeLancey, Medwick, Durocher, and the others. There was something doing all the time in the clubhouse and in the dugout, but don’t get any idea they weren’t out there to play baseball and to win. They gave 100 percent. I’m happy to have been a small part of the Gang. They were a great bunch.”

Healy felt Frisch was the brains on the club. “He was a good guy and a tough guy; so was Leo Durocher in my book.” Healy was grateful for his time in the big leagues: “I felt lucky to be playing baseball at that time because of the Depression and jobs were so hard to find.” Having had a ringside seat for Joe Medwick’s slide into Marv Owen in the seventh game of the 1934 World Series, Healy was asked for his opinion on the incident that led to a riot. “I have read and heard stories about Joe Medwick and Marty (Marv) Owen, in the series and a fistfight. Honestly, I think Medwick accidentally kicked him and Marty thought otherwise.”

Years after he left baseball, Healy’s interest remained strong. “I missed the game terribly; I missed those I played with. … My interests today are as high today in baseball as they were in my playing days, no doubt even higher now that my nephew is up there with Kansas City.”

Healy and Dizzy Dean remained friends over the years. The incongruous duo met up at the 1973 Hall of Fame celebration and there Healy even got together with Bill Terry, his former teammate, manager, and, for a while, nemesis.

Healy died on February 12, 1997, at the age of 86. He was buried at St. Jerome Cemetery alongside his brother Daniel and sisters, Anne and Mary.

Healy’s obituary said he was the last surviving player from the 1934 Cardinals championship team. That was incorrect; in May 1999 Clarence Heise, a pitcher who appeared in one game for the team, died at 91 in Winter Park, Florida. They were the last of the team whose year of glory fascinates latter-day fans of the game.14

Notes

1 Some sources list Healy’s full name as Francis Xavier Paul Healy. Neither Ancestry.com nor his obituary in the local paper reflect this.

2 Healy’s player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

3 “McGraw Believes He Has Another Melvin Ott in 17-Year Old Francis Healy,” New York Graphic, April 3, 1930.

4 Charles C. Alexander, John McGraw (New York: Penguin Group, 1988), 270-271.

5 “He Who Runs Away,” unnamed newspaper in Healy’s Hall of Fame file, April 17, 1930.

6 Statistics for this article from either Baseball-reference.com or Retrosheet.org.

7 Alexander, John McGraw, 304-308.

8 “Grimes Released,” Moberly (Missouri) Monitor-Index and Democrat, May 15, 1934.

9 “Series Checks Mailed Out,” The Sporting News, November 1, 1934, 6.

10 “Quiet Man Francie Healy one of Holyoke’s Greats,” Springfield (Massachusetts) Union-News & Sunday Republican, March 13, 1997. The author thanks Mathew Jaquith of the Springfield City Library for providing articles from the Union-News & Sunday Republican.

11 Comments in Healy’s Hall of Fame player file suggest some sort of mental incapacity, perhaps brought on by the stress of playing ball.

12 Hall of Fame player file.

13 All quotes by Healy are from his player file at the Hall of Fame.

14 Baseball-reference.com.

Full Name

Francis Xavier Paul Healy

Born

July 29, 1910 at Holyoke, MA (USA)

Died

February 12, 1997 at Springfield, MA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.