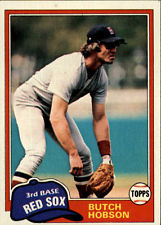

Butch Hobson

Before Curt Schilling and the bloody sock in 2004, one player who personified toughness in a Boston Red Sox uniform was Butch Hobson. Hobson’s legacy is that of a power-hitting third baseman who brought a football mentality to the diamond in the way he played through pain and gave every ounce of effort on the field that his body could muster.

Before Curt Schilling and the bloody sock in 2004, one player who personified toughness in a Boston Red Sox uniform was Butch Hobson. Hobson’s legacy is that of a power-hitting third baseman who brought a football mentality to the diamond in the way he played through pain and gave every ounce of effort on the field that his body could muster.

Clell Lavern Hobson Jr. was born on August 17, 1951, in Tuscaloosa, Alabama. An American Legion and Bessemer (Alabama) High School Most Valuable Player, he followed in his father’s footsteps to play football and baseball at the University of Alabama. His father, a three-year letterman at quarterback for Alabama, was Hobson’s football coach at Bessemer High. Butch was named to the All-Jefferson County team as a quarterback. He was a safety and backup quarterback at Alabama under legendary coach Paul “Bear” Bryant. In the 1972 Orange Bowl national championship game, won by Nebraska over Alabama by 38-6, Hobson ran the wishbone offense for the Crimson Tide after starting quarterback Terry Davis was injured in the fourth quarter. Alabama’s most successful offensive options in that game were the option running and draw plays executed by their quarterback tandem. According to Herb Crehan in Red Sox Heroes of Yesteryear, Hobson carried the ball 15 times, rushing for 59 yards in the Orange Bowl.

Entering his senior year at Alabama, Hobson decided to concentrate solely on baseball. In 2004 he said, As reported to Kevin Glew in Baseball Digest, “I told Coach Bryant my decision and he told me, ‘Well, Butch, from what I’ve seen of you on the baseball field, you’ll be playing football for me next year.’ “1 Hobson’s choice proved to be a wise one. In 1973 he was the team leader in hits (38), home runs (13), and RBIs (37), and tied for the team lead in runs (20). The 13 home runs were a Southeastern Conference record. He was named to the ABCA All-South Region Team and was a First Team All-SEC selection. Hobson lettered in baseball at Alabama in 1970, 1972, and 1973, playing for coaches Joe Sewell and Hayden Riley. He hit .250 for his collegiate career (80-for-320) with 18 homers and 54 RBIs. In 1993 Hobson was named to Alabama’s All-Century baseball team in commemoration of the school’s 100th anniversary of baseball.

Hobson was selected by the Red Sox in the eighth round of the 1973 amateur draft and was signed to a contract by Red Sox scout Milt Bolling on August 1, 1973. He was assigned to Winston-Salem where he hit a mere .179 in 17 games. His numbers improved over a full season at Winston-Salem as he hit .284 with 14 homers and 74 RBIs in 1974 and they earned him a promotion to Bristol of the Eastern League. His 15 homers, 73 RBIs, and .265 batting average at Bristol in 1975 helped secure him a call-up to Boston in September.

Hobson made his major-league debut on September 7, 1975, in the second game of a doubleheader against the Brewers at Milwaukee’s County Stadium, pinch-running for Cecil Cooper in the fifth inning. In his only other 1975 appearance in the Red Sox lineup, he started at third base at Fenway Park on September 28 in an 11-4 loss to the Cleveland Indians. Hitting eighth in the order, he struck out twice and flied out to center field before getting his first major-league hit, a single off left-hander Jim Strickland in the eighth inning.

After beginning the 1976 season at Triple-A Pawtucket (in an attempt to appeal to a broader audience, the club was briefly named the Rhode Island Red Sox, but changed back to the Pawtucket Red Sox in 1977), Hobson made his 1976 debut at Fenway Park on June 28 in a 12-8 victory over the Baltimore Orioles. Getting the start at third base and batting second, he went 2-for-5, doubling off Jim Palmer and hitting his first major-league homer in the sixth off Rudy May. Center fielder Paul Blair missed catching Hobson’s drive to center, allowing Hobson to circle the bases with Cecil Cooper ahead of him for the inside-the-park home run.

Hobson played 76 games at third base in 1976 for the Red Sox as the successor at the hot corner to Rico Petrocelli. Petrocelli was winding down a 13-year career with the Red Sox, hitting only .213 in 85 games in his final season. Hobson, made the everyday third baseman by new manager Don Zimmer (who replaced Darrell Johnson after the All-Star break), hit .234, contributing eight homers and 34 RBIs.

The 1977 season was Hobson’s breakout year and also his finest as a major leaguer. He smashed 30 round-trippers, establishing a Red Sox record for third basemen. It has often been printed that Hobson set his standard for Red Sox third basemen while hitting in the ninth spot in the batting order. In fact, in 159 games in 1977, he hit third in five games, sixth in 12 games, seventh in 47 games, eighth in 89 games, and ninth in only six games. He hit no homers in the nine spot. Twenty-eight of his 30 homers were hit in the seventh or eighth spot in the batting order. The 1977 Red Sox offensive juggernaut, affectionately known as the Crunch Bunch, hit a then team-record 213 home runs, 21 more than the White Sox, who were second in the major leagues. Five Red Sox hit more than 25 homers, with Jim Rice leading the American League with 39.

The club hit five or more homers in eight games. They slugged 33 home runs in a 10-game stretch from June 14 through June 24 (establishing a major-league record) and 16 in three games against the New York Yankees June 17-19 (also a major-league record). On July 4 the Red Sox hit a then-record eight home runs (still a Red Sox team high), including seven solo shots (still a single-game record) in a 9-6 pounding of the Toronto Blue Jays in Boston. Hobson’s free-swinging ways combined to produce a career-best .265 batting average, 30 homers, 33 doubles, 112 RBIs, and 162 strikeouts (as of 2014 still a Red Sox record for a right-handed batter) in 159 games at third base. Hobson put together an 18-game hitting streak. He was named the BoSox Club Man of the Year for 1977 for his contributions to the success of the team and for his cooperation in community projects.

Old football injuries sustained on the artificial turf at Alabama contributed to a nightmarish 1978 season defensively for Hobson. Bone chips floating around in his right elbow made every throw from third base an adventure. His impairment would often cause his arm to lock up, disrupting his throws. A familiar sight in 1978 was Hobson making a play and then rearranging the bone chips in his elbow. In addition to his sore arm, Hobson was hobbled by cartilage damage in both knees and a torn hamstring muscle. He played 133 games at third base in 1978 (he also served as the DH in 14 games), and he drove in 21 runs in a 10-game stretch from April 14 through 23. Hobson’s 43 errors yielded a fielding percentage of .899, the first time since 1916 that a regular player’s defensive average registered below .900 for the season.

Manager Zimmer, accurately characterizing Hobson as a “gamer,” refused to pull him out of the lineup. While his defense suffered, he would manage to be a productive hitter, belting 17 homers and driving in 80 runs. He finally asked out of the lineup on September 22 in preparation for postseason elbow surgery, with Jack Brohamer filling in at third and Hobson still serving as a DH. In the 5-4 playoff loss to the Yankees on October 2, Hobson was 1-for-4 (a single) in the number seven spot in the order while serving as the designated hitter.

Hobson came back in 1979 to play 142 games at third base. He slugged a career-high .496, batting .261 with 28 homers and 93 RBIs. Shoulder problems in 1980 prompted Zimmer to replace him at third with rookie Glenn Hoffman, who hit .285 in 110 games, while Hobson’s batting average dropped to .228 (with 11 home runs and 39 RBIs) in 93 games, 57 of them at third base. On May 31 the Red Sox hit six home runs, including a back-to-back-to-back trio by Tony Perez, Carlton Fisk, and Hobson, in a 19-8 loss to the Brewers. On June 12, 1980, Hobson had the only multi-homer game of his career, swatting a pair in a 13-2 win over the Angels in Anaheim.

On December 10, 1980, Hobson was traded with Rick Burleson to the California Angels for third baseman and future 1981 batting champion Carney Lansford, outfielder Rick Miller, and pitcher Mark Clear. He was limited to 85 games with the Angels in the strike-shortened 1981 season as a result of elbow injuries and a separated shoulder, hitting .235 with 4 homers and 36 RBIs. On March 24, 1982, Hobson was traded to the Yankees for pitcher Bill Castro. He hit only .172 in 30 games with New York, his final major-league stop as a player. In eight years as a player in the majors, Hobson had a career average of .248 with 98 home runs and 397 RBIs. He drove in four runs in a game seven times in his career with Boston and once with the Angels. Among Red Sox third basemen defensively, entering the 2005 season, Hobson was seventh in career games played for the Red Sox, eighth in putouts (473), seventh in assists (1,042), and eighth in double plays (85).

The way Hobson threw his body around on the field for the good of the team contributed to a shortened major-league career. It also helped make him a fan favorite. In a 2002 interview, Hobson explained his popularity: “Boston Red Sox fans are supportive. … Whether a guy goes 0-for-20, as long as you are out there and giving 110 percent every day, that’s all they care about. They’re rooting for that blue-collar guy that runs through walls. They want that guy who will dive into the stands for a ball because they know, in the long run, it’s going to be what helps them come out on top. As long as you can continue that when you play [in Boston], you’re going to be very well accepted.”2

After playing one partial and three full seasons in Columbus, the Yankees’ Triple-A farm club and ending his playing career, Hobson returned in a manager’s role. In 1987 and 1988 he managed the New York Mets’ team in Columbia in the Class-A South Atlantic League. He joined the Red Sox system in 1989, managing New Britain of the Double-A Eastern League. His 1990 squad advanced to the final round of the Eastern League playoffs. Around this time, Hobson also served a stint as manager of the Winter Haven Super Sox in the short-lived Senior Professional Baseball League. In his fifth season as a minor-league manager, in 1991, Hobson guided the Triple-A Pawtucket Red Sox to a 79-64 record and a first-place finish in the International League East Division. His PawSox lost in the Governor’s Cup Championship, getting swept, 3-0 by his last minor-league team as a player, the Columbus Clippers. Hobson was honored by Baseball America as its Minor League Manager of the Year and by the International League as its Manager of the Year. He was viewed by Red Sox management as a rising star as a manager.

On October 8, 1991, the Red Sox fired manager Joe Morgan and named Hobson as his replacement. “We couldn’t risk losing such a talent in our organization,” said general manager Lou Gorman.3 The Red Sox hoped they would be getting a managerial version of the tough player Hobson had been. But Hobson’s toughness as a player was not evident in his performance as a manager as perceived by the media. (Boston Globe columnist Dan Shaughnessy often referred to manager Hobson as “Daddy Butch.”) This did not bode well during a three-year period in which the Red Sox seriously underachieved.

Hobson lost his first two games as manager in 1992 in New York. The season opener on April 7 was lost by a 4-3 score with Roger Clemens on the mound for the Red Sox. His first win was a 19-inning 7-5 decision over the Indians at Cleveland Municipal Stadium on April 11. The Red Sox, at 73-89, were seventh and last in the American League East, their worst finish since 1966 – and their first last-place finish since 1932. After Roger Clemens (18-11), Frank Viola (13-12) was the only pitcher with a won-lost percentage over .500. Offensively, the team hit .246, 13th out of the 14 American League teams. Jack Clark, after hitting 28 homers in 1991, hit only five in 1992 and hit .210 in the final season of his career. Wade Boggs hit a career-low .259 and left for the Yankees after the season. Mike Greenwell hit .233. Tom Brunansky led the team with 15 homers and 74 RBIs.

The 1993 season saw the batting average improve to .264 with the emergence of Mo Vaughn (29 homers, 101 RBIs). However, Roger Clemens had his worst season as a professional (11-14, 4.46 ERA, a season in which he had been bitten on the pitching hand by his dog) and the team was again mired in the second division, finishing fifth in the AL East with a mediocre 80-82 record.

The players strike shortened the 1994 season, and the Red Sox compiled a 54-61 record and finished fourth in the AL East. Clemens led the staff with a 9-7 record. The offense, led by Vaughn and John Valentin, hit a combined .263 (12th in the AL) while the team ERA of 4.93 (ninth in the AL) is the only other fact one needs to figure out what happened with this team. New general manager Dan Duquette shipped players in and out trying to light a fire under the Red Sox. After the season he decided to ship out his manager as well, firing Hobson and bringing in Kevin Kennedy to manage the team.

Don Zimmer served as Hobson’s bench coach in 1992 and theorized in his book Zim that substance abuse, alcohol in particular, played a role in Hobson’s failure as a Red Sox manager. His substance-abuse problem was exposed to all in May 1996. After his dismissal from the Red Sox, Hobson became the manager of the Triple-A Scranton/Wilkes-Barre Red Barons. On May 4, 1996, his team was in Pawtucket to play the PawSox. Hobson was arrested in his hotel room on a felony charge of cocaine possession. Approximately 2.6 grams of cocaine (about $120 in value) were alleged to have been found in Hobson’s shaving kit, having been sent to Hobson in a Federal Express package by a former friend from Alabama named Jerry Poe. Poe owed Hobson money and sent the supposedly unsolicited drugs in payment of that debt. On August 8, 1996, Hobson was fired by the Philadelphia Phillies, Scranton’s parent club. He was able to resolve the drug charge without a guilty finding in exchange for entering a first-offender program and performing approximately 60 hours of community service. He denied ever using cocaine while managing the Red Sox or the Red Barons. He has acknowledged a past history with the drug that began when he was a player. “I came up in an era when that (using drugs) was what you were supposed to do. As a good old boy from Alabama, I thought that was the way to fit in. It probably cost me three or four years of baseball,” he said.4

After his termination from the Red Barons, it was the Red Sox who gave Hobson another chance. In February 1997 he was hired as a special-assignment scout. In 1998 he continued his comeback as manager of the Sarasota Red Sox in the Class-A Florida State League. Finally, on December 2, 1999, Hobson returned to New England as the manager of the Nashua (New Hampshire) Pride of the independent Atlantic League. As the third manager in the team’s history, Hobson led the 2000 Pride to the Atlantic League title. The championship was New Hampshire’s first professional sports title in over 50 years. Hobson’s 2001 squad was eliminated in the first round of the playoffs. In 2003 the Pride returned to the championship series before they lost in five games to the Somerset Patriots, the team they had swept for the 2000 title.

In 2007 Hobson led the Pride to another championship, the Can-Am League crown. In 2011, he became manager of the Independent Atlantic League’s Lancaster (Pennsylvania) Barnstormers. In 2014 the Barnstormers won the league championship.

Hobson has three grown daughters, Allene, Libby, and Polly, from his first marriage, and three boys, K.C., Hank, and Noah, and a daughter, Olivia, from his second marriage, to his wife, Krystine.

Last revised: October 28, 2014

A version of this biography was originally published in ” ’75: The Red Sox Team That Saved Baseball,” edited by Bill Nowlin and Cecilia Tan, and published by Rounder Books in 2005.

Sources

Ashmore, Mike, “Ten Questions With Butch,” AtlanticLeagueBaseball.com, September 14, 2004.

Boston Red Sox 1977, 1978, 1979 Yearbooks.

Boston Red Sox 1976 Press-TV-Radio Guide.

Boston Red Sox 2005 Media Guide.

Brooks, Scott, “Hobson’s Choice: Pride Boss Staying in Nashua,” New Hampshire Union-Leader (Manchester), November 23, 2004.

Comey, Jonathan, “Hobson finally back where he belongs,” South Coast Today, February 8, 1997.

Complete Baseball Record Book, 2004 Edition, The Sporting News, 2004.

Courtney, Will, “The fall and rise of Butch,” August 10, 2000. Eagle-Tribune, (Lawrence, Massachusetts), accessed via eagletribune.com,

Crehan, Herb, Red Sox Heroes of Yesteryear (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Rounder Books, 2005).

Dewey, Donald, and Nicholas Acocella, The New Biographical History of Baseball (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2002).

Gammons, Peter, Beyond the Sixth Game (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1985).

Glew, Kevin, “Former Third Baseman Butch Hobson: Players who left the game on their own terms,” Baseball Digest, December, 2004.

Golenbock, Peter, Red Sox Nation (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2005).

Halvatgis, Jenna, “Hobson’s Hope,” South Coast Today, May 11, 1998.

Hickling, Dan, “Hobson’s Choice,” minorleaguenews.com, May 6, 2005.

Kahn, Roger, October Men (New York: Harcourt Inc., 2003).

Linn, Ed, The Great Rivalry (New York: Ticknor & Fields, 1991).

Malinowski, W. Zachary, and John Castellucci, New England Sports Service, “Butch Gets Busted,” South Coast Today, May 9, 1996.

McDonald, Joe, The Independent Interview: Butch Hobson, alindependent.com, July 9, 2004.

Petraglia, Mike, “Where have you gone, Butch Hobson?” mlb.com, February 19, 2002.

Smith, Curt, Our House (Chicago: Masters Press, 1999).

Stout, Glenn, and Richard A. Johnson, Red Sox Century (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2000).

Thorn, John, et al, Total Baseball, Sixth Edition (Kingston, New York: Total Sports, 1999).

Zimmer, Don, with Bill Madden, Zim: A Baseball Life (Chicago: Contemporary Books, 2001).

Websites

Notes

1 Kevin Glew, “Former Third Baseman Butch Hobson: Players who left the game on their own terms,” Baseball Digest, December 2004.

3 Boston Globe, October 9, 1991.

4 Glew.

Full Name

Clell Lavern Hobson

Born

August 17, 1951 at Tuscaloosa, AL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.