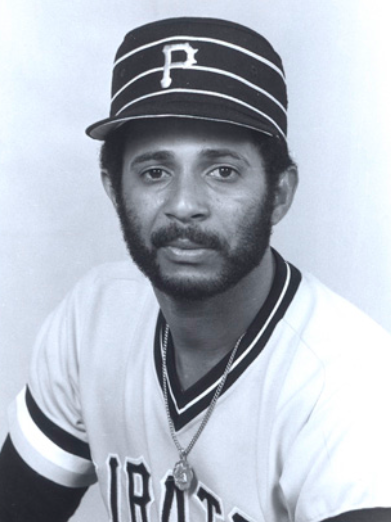

Frank Taveras

When the 2015 season opened, Dominicans made up nearly 10 percent of the major leagues’ talent pool.1 They weren’t so common in 1971, though, when Frank Taveras made it to the majors for the first time. He was just the 28th of his countrymen to reach the top level — this list has now grown well beyond 600.

Taveras played eight full big-league seasons and parts of three others from 1971 to 1982. He was a type of player who once was archetypal — the light-hitting but speedy shortstop. In 4,399 big-league plate appearances, Taveras hit just two home runs, and his slugging percentage was just .313. But he stole 300 bases, including 70 in 1977, when he led the majors.

With the glove, Taveras was erratic; he made many brilliant plays and muffed easy ones.2 As a result, the fans in Pittsburgh, where he played most of his big-league career, often booed him. “Every time he made a mistake, everybody was all over him,” said Chuck Tanner, his manager with the Pirates from 1977 until April 1979, when Taveras was traded to the New York Mets for Tim Foli. “I think he’s always had a tough time in Pittsburgh because the fans thought he couldn’t do anything right even the year that he led the league in stolen bases.”3 Taveras was also “an emotional player [who] got extremely upset by criticism and rulings by official scorers.”4

Franklin Crisóstomo Taveras Fabián was born on December 24, 1949, though at times his year of birth was listed as 1950. Taveras’s birthplace was Las Matas de Santa Cruz, though again, while he was an active player, it was sometimes given as Villa Vásquez, a place about half an hour north by bus.5

Las Matas de Santa Cruz is the largest city in Monte Cristi province, in the northwestern corner of the Dominican Republic. It’s really a town, though; even today its population is less than 20,000. Further information about Frank’s parents, Señor Taveras and Señora Fabián, is not presently available. Frank was one of at least five children. He had two brothers (Ramón and Rodrigo) and two sisters (Magalys and Eunice).6

The baseball culture runs deep in the Dominican Republic, including Monte Cristi. The local heroes were the Olivo brothers, Diómedes and Chi-Chi, who both made it to the majors as “rookies” in the 1960s, when they were 41 and 35, respectively. It is a rural area; the young Frank Taveras grew up playing ball in the countryside.

It’s no surprise that the man who signed Taveras was Howie Haak, the superscout who blazed trails in searching for talent across Latin America. Haak got Taveras for a bonus of $3,500 in January 1968. At the time, the 18-year-old shortstop was playing for the National Police team. He was supposed to be serving police duty at a livestock fair, but he paid a friend 20 Dominican pesos (then officially equal to US$20) to take his place. He then went to Estadio Quisqueya in Santo Domingo, where he met Haak, who took him to the hotel El Embajador. There the signing took place.7

Taveras then began his pro career in the spring of 1968. In his first three seasons as a minor leaguer, he played largely at the Class-A level, with five different teams. In the winter of 1968-69, he began to play in his homeland’s professional league. He joined Águilas Cibaeñas and spent 10 seasons with that club. There too, his first three years were a learning experience, but mainly from the bench — he played 10 to 20 games per season, about 30 percent of the team’s total. He hit .292 in 130 total at-bats.8 At home, Taveras had two nicknames: Boroto (which apparently has no particular meaning) and Berenjena (“Eggplant”).9 Their origins are uncertain.

The Pirates invited Taveras to spring training in 1969. It was probably then that the young Dominican first met the great Roberto Clemente, whom he later called “my guide, my mentor, my counselor.”10

At age 21 in 1971, Taveras began a rapid ascent. He played 87 games in Double A and 48 at Triple A. According to one report, he “fielded brilliantly” after joining the Pirates’ top affiliate, in Charleston, West Virginia. The Charlies’ manager, Joe Morgan (who later became skipper of the Boston Red Sox), said, “If I had known Taveras was going to play shortstop the way he did, he would have been in our lineup sooner, and could have meant eight or 10 more victories to us.”11

When the major-league rosters expanded that September, Taveras got his first call-up to “The Show.” He got into one game for the eventual World Series champs, on September 25 at Shea Stadium in New York. That afternoon’s contest ran 15 innings. In the top of the 15th, with a runner on second base and one out, Mets-killer Willie Stargell was intentionally walked. Taveras came on as a pinch-runner, but the next batter, Carl Taylor, grounded into a 6-4-3 double play.

In the winter of 1971-72, Taveras became a regular for Águilas Cibaeñas — and a member of a Dominican League champion for the first time. Therefore, he got to play in the Caribbean Series, in which the region’s winter-ball champions faced each other in a round-robin tournament. Taveras was on three other Dominican champion teams (in 1975, 1976, and 1978). He recalled with particular satisfaction the battles against the Licey Tigres.12 Unfortunately for Frank, the Dominican team did not win any of the four Caribbean Series in which he appeared. Overall, he hit .243 in that competition (19-for-78, all singles, in 21 games).13

Taveras spent all of the US minor-league season in 1972 with Charleston. That June, Pittsburgh beat writer Charley Feeney noted that the Pirates were keeping a close watch on the young shortstop, saying that he could be called up if Gene Alley’s knee problems continued.14 Soon after, Taveras was the starting shortstop for the International League All-Star Team, which faced the Atlanta Braves at Norfolk, Virginia, on July 10. That September the Pirates called him up again, and he got into four games as a substitute shortstop. He went hitless in his first three big-league at-bats. He also witnessed Clemente’s 3,000th hit in the majors.

Taveras returned to Charleston once more, in 1973. The previous November, Pirates manager Bill Virdon had said, “Taveras has to play. I’m not looking at him as a utilityman. I would rather have him playing every day at Charleston than sitting on our bench.”15 Ahead of him in Pittsburgh were veterans Alley and Jackie Hernández, who had been with the Pirates since 1963 and 1971, respectively. Neither man was known for his hitting, yet that July Pittsburgh obtained an even lighter-hitting glove man — Dal Maxvill — to play short.

In the middle of the 1973 season, Charley Feeney wrote that Taveras’s stock had slid with the Pittsburgh front office.16 The Pirates did not call him up after Charleston won the International League pennant. Nonetheless, by the end of the year he was still widely regarded as one of the blue-chip prospects in the IL.17

After the 1973 season, the big-league careers of both Alley and Hernández were over. Alley retired and Hernández wound up trading places with Taveras — in 1974, the Cuban went to Charleston and the Dominican made the Pittsburgh roster, never to return to the minors. In search of younger players who could put speed in the lineup, the Pirates released Maxvill on April 20. The Associated Press wrote, “Taveras has long been regarded as the heir apparent to the post. … Pirates’ officials feel Taveras has all the tools to become a top-flight infielder — the arm, speed, and range. Only his steadiness is questioned.”18

“They really surprised me,” said Taveras in 1975. “Maxvill was a good player and he’d been around a long time.” During the first half of the season, Taveras alternated with Mexican shortstop Mario Mendoza, but Frank carried the load at short during the second half. He committed 31 errors, but credited second baseman Rennie Stennett with helping him to improve in the field. In 126 games (107 starts at shortstop), Taveras hit .246 with no homers and 26 RBIs. Batting coach Bob Skinner encouraged him to choke up on the bat to gain greater control and make better contact.19

It’s true of athletes in general, but psychology was an especially important factor for Taveras. He said that Danny Murtaugh, the Pirates’ outstanding manager, “gave me the confidence to realize my game without pressure.”20

After missing the playoffs in 1973, Pittsburgh won the National League East again in both 1974 and 1975. The Pirates lost both times in the NL Championship Series, first to Los Angeles and then to Cincinnati. That was the only big-league postseason action for Taveras, who got into five games overall with one hit in nine at-bats. He wept in disappointment over not reaching the World Series.21

Taveras (who sported a bushy Afro in those days) remained the Pirates’ primary shortstop from 1975 through 1978. Mario Mendoza was also with Pittsburgh throughout that period, but despite his soft hands, Mendoza’s notoriously weak hitting kept him in reserve. After the 1976 season, the Pirates traded away another player who became a good major-league shortstop, Craig Reynolds.

During the 1975-78 period, Taveras averaged 146 games, 140 starts at shortstop, and 576 plate appearances per season. He hit .250, with one home run and 114 RBIs. The subject of Taveras’s power — or lack thereof — came up in a friendly bet with Willie Stargell. In an April 1976 exhibition game, Taveras hit an inside-the-parker off Al Hrabosky. Stargell said, “Told him last year there ain’t no way he can do it [hit a homer]. And I told him if he did I’d pay him 25 bucks during an exhibition game and $100 during the season. … He’s been telling me all spring how he’s been lifting weights and how strong he is.”22

On August 5, 1977, Taveras finally got his first round-tripper in a big-league regular-season game (he’d hit six in the minors). It was an inside-the-park grand slam off Doug Capilla of the Reds at Cincinnati’s Riverfront Stadium. It came after Taveras was at the center of a bench-clearing brawl in the opener of that night’s doubleheader. Veteran Cincinnati reliever Joe Hoerner plunked Taveras in the ninth inning because he thought that the shortstop had been rubbing it in by stealing a base in the third when the Pirates were already up 7-0. Taveras retaliated by throwing his bat, and in the ensuing melee, Hoerner punched Taveras in the face while Reds catcher Bill Plummer was holding Frank’s arms.23

Controlling his temper and dealing with the displeasure of fans remained difficult for Taveras. One stretch in early July 1977 captured this. After a tough 14-inning loss on July 1, in which he went 0-for-6 and was ejected, he reportedly had harsh words for umpire Ed Sudol and was fined by the league. On July 5 he tossed his batting helmet in disgust when the home crowd booed him in each of his four at-bats. He said, “People who watch baseball think bad of me because I’m not hitting the ball like you’re supposed to. But you’ve got to take it because they pay to get in.”24

Taveras emerged as a major basestealing threat in 1976, when he swiped 58 and got caught just 11 times. “The Pittsburgh Stealer” became his nickname. He credited the tutelage of Maury Wills, one of the all-time greats in this area, whom the Pirates had retained as an instructor during the previous Dominican winter season. The sessions ran for just two weeks but had lasting impact. Wills gave Taveras a variety of technical tips — but perhaps even more important, said Taveras, was how “he taught me not to be afraid.”25

When Taveras led the majors with 70 steals in 1977, he got caught just 18 times. On September 17, 1977, he stole his 64th base of the year at Montreal’s Olympic Stadium. That broke the club record of 63, set by Max Carey in 1916. Omar Moreno set a new Bucs standard in 1978, and topped it in each of the next two seasons. Yet many years later, Taveras still prized the replica base he was awarded for setting his record.26

Among opposing pitchers, Taveras found Steve Carlton and Rick Reuschel the most difficult to steal against. Carlton had a way of lulling runners into moving off first base with a slow motion to the plate; then he would look to trap them. Reuschel had an excellent pickoff move.27

In 1978, however, Taveras was much less successful as a basestealer; he stole 46 but opposing catchers nailed him a league-high 25 times. However, he reached a career high with 182 base hits. He thought that curbing his winter-ball play and lifting weights helped him keep up his strength as the season wore on. He was also trying to stay calmer, especially with umpires.28

In his last winter with Águilas Cibaeñas, 1977-78, Taveras played just nine regular-season games. He concluded his career at home with a batting average of .265 in 1,349 at-bats across 364 games. He never hit a homer in Dominican play, but he stole 64 bases.29

With the glove, Taveras averaged 32 errors a year in the majors from 1975 through 1978. He made three in the first 11 games in 1979. That April 19, Pittsburgh dealt Taveras to the Mets for Foli — who was riding the bench in New York — and minor-league pitcher Greg Field. “The trade came shortly after a home game in which [Taveras] made an error on one ball and then failed to charge one he should have had.”30 The next inning, Dale Berra replaced Taveras. The Pirates announced that Taveras had “an intestinal virus.”31

When double-play partner Rennie Stennett heard about the trade, he said, “[Taveras] appeared to be playing in a trance for the last few days. I don’t know what it was, but I wish him good luck in New York.”32 Chuck Tanner added, “He’s a good ballplayer and I think he’ll do better in a new location.”33

Howie Haak opposed the trade. That October, after the Pirates had won the NL pennant, the scout said, “I thought we were giving up too much range in Taveras. I told them my objections. They went ahead and made the trade anyway.” As UPI wrote, it turned out to be the best advice the Pirates never took.34 The fiery Foli was steadier in the field, as expected, and became an important cog in the 1979 World Series champion team. “I doubt if he ever helped any club more than he helped the ’79 Pirates,” said Joe L. Brown, the team’s former general manager, in 1989.35

Meanwhile, Taveras upheld Tanner’s prediction. Joe Torre, then the Mets’ manager, said in May 1979, “In the Taveras we’ve played against, and the Taveras we’re playing with, the reason for complaints hasn’t really been seen.”36 Haak also noted that October, “As it turned out, people in New York say that Taveras is playing the best shortstop the Mets have ever seen.”37 That was significant, because for many years the team had a very capable man at the position, Bud Harrelson. The arrival of Taveras also enabled Doug Flynn, a fine glove man, to play at second base, his best spot.

The Mets were then mired in one of the dreariest periods in the history of the franchise. Taveras remained their starting shortstop from the time he arrived through the strike-interrupted season in 1981. Because of scheduling differences in 1979, he played in a league-leading 164 games that year. Only six men have ever reached that mark in a single season.38

Taveras cleared a big-league fence for the only time on August 18, 1979. Again the scene was Cincinnati’s Riverfront Stadium; he hit a solo shot off Mike LaCoss of the Reds. With the Mets that year, Taveras also had nine triples, which tied a club record, and 42 steals, which was a new mark for the team (whose history to that point was short and marked by anemic offense).

Taveras started 131 games at short for the Mets in 1980, hitting a career-high .279 with no homers, 25 RBIs, and 32 steals — he was caught 18 times. He gave credit to his wife for helping him to hit well after a slow start, saying that she told him to stand up straighter. He also bunted his way on frequently.39 Taveras formed a good (albeit punchless) double-play combo with Flynn. However, he later said that Shea Stadium had one of the worst infields in the league, “especially after football started.”40 (The New York Jets of the NFL shared the ballpark then.)

In 1981 Taveras started 73 of the team’s 105 games. His basic batting line fell off to .230-0-11, and he had just 16 steals. That September New York called up rookie Ron Gardenhire, who became the Mets’ new starting shortstop in 1982. Taveras didn’t like the way he was used and asked twice to be traded.41 The Mets obliged, sending him to the Montreal Expos for pitcher Steve Ratzer in December 1981.

With the Expos in 1982, Taveras competed for the shortstop job with Chris Speier. He proclaimed “I’m not a backup player. I expect to play between 80 and 100 games at shortstop.”42 He wound up as a little-used reserve, though he got a brief trial as the starting second baseman. He got into 48 games, including 19 at second — the only time he played a position other than shortstop in the majors.43 He hit .161-0-4 in 98 plate appearances. Montreal released the 32-year-old in mid-August, and his big-league career came to an end.

In October 1982 the Pirates gave Taveras a minor-league contract and invited him to spring training. He never agreed to terms, though, and general manager Pete Peterson withdrew the offer.44

After this retirement without formal notice, Taveras remained in the Dominican Republic. For three years, from 1999 through 2001, he worked for the Pirates organization as Latin American field coordinator. Among other players, he supervised Aramis Ramírez, who emerged as a star in 2001.45

Mainly, however, he dedicated himself to religion as a member of the Charismatic Catholic movement. In 2007 he said, “Always in the afternoons I go out to preach. I spent most of my time educating those who seek God.” He had one other great passion: fishing. He became a regular at the tournaments held off Cabeza de Toro Beach, in Punta Cana, on the eastern tip of the Dominican Republic. He won the tourney twice.46

Taveras and his wife, Sotera Vargas, had two children: Franklin Jr. and Máximo.47 Franklin Jr. played in the minors and independent leagues from 1993 through 2002. He went on to become a minor-league coach and a scout. Among the numerous players whom he has helped to sign, the most notable to date (as of 2015) was pitcher Michael Pineda.

Among the uniform numbers retired by Águilas Cibaeñas is 10, worn by both Taveras (who was honored in January 1999) and another shortstop, Félix Fermín.48 In 2007, the Hall of Fame of Dominican Sports inducted Frank Taveras.

Notes

1 “Opening Day Rosters Feature 230 Players Born Outside the U.S.,” MLB.com, April 6, 2015. The pool consisted of 868 players — 750 active players on 25-man rosters, plus 118 more on disabled or restricted lists. There were 83 Dominicans.

2 Pohla Smith, United Press International, “Foli Hopes to Make Fans Forget Taveras,” May 1, 1979.

3 Associated Press, “Mets Get Taveras for Foli,” April 20, 1979.

4 Smith, “Foli Hopes to Make Fans Forget Taveras.”

5 This is visible in various editions of The Sporting News Official Baseball Register.

6 “Carlton y Reuschel, difíciles de robarle,” Listín Diario (Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic), September 15, 2007.

7 “Carlton y Reuschel, difíciles de robarle.”

8 Cuqui Córdova, “Béisbol de ayer: Franklin Taveras,” Listín Diario, April 5, 2008. The Águilas played 48 games in 1968-69 and 51 in 1969-70, according to final league standings published in The Sporting News, which did not publish that table in the 1970-71 season. The regular-season schedule in 1970-71 was 60 games, as can be determined by the 33-27 record of that year’s champion, Licey. However, not all teams played the same number of games each season.

9 Hugo López Morrobel, “Los apodos de peloteros,” El Día (Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic), February 5, 2014. With regard to the meaning of “Boroto”, the answer comes from Dominican native Eddy Olivo Cruz.

10 Bienvenido Rojas, “Franklin Taveras dice Clemente fue su guía,” Diario Libre (Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic), September 17, 2007.

11 Bill Christine, “Deep ‘Snow Job’ Convinces Alley, Pirates’ Unsigned Reduced to 2,” Pittsburgh Press, February 20, 1972: D-1.

12 “Carlton y Reuschel, difíciles de robarle.”

13 Alfonso Araujo Bojórquez, Series del Caribe: Narraciones y Estadísticas, 1949-2001, Volume 2, Colegio de Bachilleres del Estado de Sinaloa (Culiacán, Sianaloa, Mexico), 2002: 117.

14 Charley Feeney, “Bucco Super Subs Building a Fire Under the Regulars,” The Sporting News, June 17, 1972: 7.

15 Charley Feeney, “Playing Games: Rapping With Bill Virdon,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, November 30, 1972: 23.

16 Feeney, “Playing Games: Some Shorties.”

17 A.L. Hardman, “Velez, Taveras Rate as Int’s Best,” The Sporting News, October 13, 1973: 29.

18 Associated Press, “Bucs Cut Dal; Downing ‘Catches On,’ ” April 22, 1974.

19 Ed Rose Jr., “Taveras Never Heard of Sophomore Jinx,” Beaver County (Pennsylvania) Times, March 12, 1975: D-3.

20 Rojas, “Franklin Taveras dice Clemente fue su guía.”

21 “Carlton y Reuschel, difíciles de robarle.”

22 Ed Rose Jr., “Taveras (honest) hauls out lumber,” Beaver County Times (Beaver, Pennsylvania), April 7, 1976: D-1.

23 Fred McMane, United Press International, “Taveras Scores Knockout After Decking,” August 6, 1977.

24 “Pirate Shortstop Hazy About Sudol Death Wish,” Associated Press, July 5, 1977.

25 United Press International, Scott MacLeod, “Pirates’ Taveras Credits ‘Teacher,’ ” August 5, 1976.

26 “Carlton y Reuschel, difíciles de robarle.”

27 “Carlton y Reuschel, difíciles de robarle.”

28 “Self-Control Taveras Goal,” Associated Press, March 28, 1978; “Frank Taveras: Pirate Shortstop Has Hot Bat, a New Image,” Associated Press, June 23, 1978.

29 Córdova, “Béisbol de ayer: Franklin Taveras.”

30 Smith, “Foli Hopes to Make Fans Forget Taveras.”

31 Charley Feeney, “Pirates Ship Taveras to Mets, Acquire Foli,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, April 20, 1979: 39.

32 Feeney, “Pirates Ship Taveras to Mets, Acquire Foli.”

33 “Mets Get Taveras for Foli.”

34 United Press International, “Pirate Scout Opposed Deal for Tim Foli,” October 10, 1979.

35 Ed Bouchette, “The Search Goes On: Bucs Still Looking for Shortstop to Replace Alley,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, April 3, 1989: B-4.

36 Jim O’Brien, “Who Got Better of Taveras Trade?,” Pittsburgh Press, May 15, 1979: B-9.

37 “Pirate Scout Opposed Deal for Tim Foli.”

38 In 1962 Maury Wills (Dodgers) played in 165 and José Pagan (Giants) played in 164. That year those two teams faced each other in a three-game playoff. In 1965 Ron Santo and Billy Williams each played in 164 games for the Cubs; César Tovar also played in 164 for the Twins in 1967. Those three men achieved their totals because their teams each played in two games that ended in ties, which were counted in individual statistics but not in the standings.

39 Dan Donovan, “Taveras’ New Stance a Big Hit With Mets,” Pittsburgh Press, June 1, 1980: D-8.

40 Ian MacDonald, “Dogfight for Infield Spots as Taveras Arrives,” Montreal Gazette, March 8, 1982.

41 Ibid.

42 Ibid.

43 In the minors, he had played some second base and occasionally appeared at third; he had also played second at times in winter ball.

44 Bill Stieg, “Farewell to Frank,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, December 17, 1982: 20. Charley Feeney, “Pittsburgers,” The Sporting News, December 27, 1982: 40.

45 “Carlton y Reuschel, difíciles de robarle.” Newspaper transaction listings show that the Pirates named Taveras Latin American field coordinator in November 1999. John Perrotto, “This Time, Bucs Say Ramirez Is Ready,” Beaver County Times, March 9, 2000, B1.

46 “Carlton y Reuschel, difíciles de robarle.”

47 “Taveras se regocija al ver concretarse un gran sueño,” Listín Diario, September 15, 2007.

48 Cuqui Córdova, “Béisbol de ayer,” Listín Diario, April 12, 2008.

Full Name

Franklin Crisóstomo Taveras Fabián

Born

December 24, 1949 at Las Matas de Santa Cruz, Monte Cristi (D.R.)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.