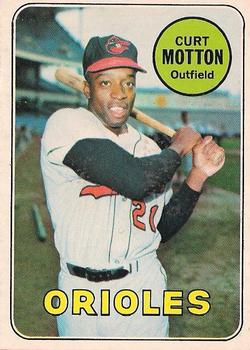

Curt Motton

“(Curt) Motton has been Baltimore’s best pinch-hitter ever since I’ve been managing this club. He was an automatic choice in this spot.”

— Orioles manager Earl Weaver after Motton’s game-tying double helped Baltimore come from behind to beat Oakland’s Vida Blue in the 1971 American League Championship Series1

Curt Motton grew up in the Oakland, California, housing projects with future major leaguers Willie Stargell and Tommy Harper. Stargell became a Hall of Famer and Harper had a 15-season big-league career. In Motton’s eight major-league seasons he was never a regular, but he found his big-league niche as a pinch-hitter.

Curt Motton grew up in the Oakland, California, housing projects with future major leaguers Willie Stargell and Tommy Harper. Stargell became a Hall of Famer and Harper had a 15-season big-league career. In Motton’s eight major-league seasons he was never a regular, but he found his big-league niche as a pinch-hitter.

Curtell Howard Motton was born on September 24, 1940, in Darnell, Louisiana. The eldest son of Robert Motton and the former Mary Lean Coleman, he was third child of nine born to the couple (four boys and five girls). Motton (pronounced MOE-ton) was a French surname, originally pronounced (MOE-tawn), and the spelling evolved over the years. His mother was a housewife and homemaker, while his father worked in construction. When Motton was 5 or 6 years old, the family moved to Oakland to pursue better job opportunities.

Motton, Stargell, and Harper attended Encinal High School together and they starred on the gridiron as well as the diamond. Harper quarterbacked the school football team, Stargell played end and Motton was an elusive halfback. Though he was only about 5-feet-7½ inches tall and weighed 175 pounds when he reached the majors, the diminutive Motton was a four-sport athlete at Encinal, also participating in basketball and track. (More recently, the school sent 2003 National League Rookie of the Year Dontrelle Willis and 2007 NL Most Valuable Player Jimmy Rollins to the big leagues.)

Motton admired Milwaukee Braves star Hank Aaron for the way he held and swung his bat, and proved to be a pretty good hitter of his own in helping the team from Hayward, California, reach the Connie Mack World Series in St. Joseph, Missouri, after his high school graduation. Then it was off to the University of California by way of Santa Rosa Community College. When the Chicago Cubs offered him $4,000 to sign in summer of 1961, the 20-year-old Motton accepted it and commenced his professional baseball career the following year.

He earned Northern League All-Star recognition for the St. Cloud Rox in 1962, hitting .291 with 13 home runs and 69 RBIs in 125 games. He was honored as the circuit’s Player of the Month after batting .347 in May. But despite his auspicious debut, he didn’t stay in the Cubs organization for long. The Baltimore Orioles acquired an entire outfield in the first-year player draft in November 1962: future All-Star Paul Blair (from the Mets), Dave May (from the Giants), and Roger Sorenson, who never advanced past Single-A. Baltimore farm director Harry Dalton knew about Motton’s questionable throwing arm and wasn’t sure he needed to draft a fourth outfielder that day. So Dalton called Billy DeMars, skipper of Baltimore’s Northern League affiliate, to get a first-hand opinion. “Good bat and he can run,” DeMars assured him. “Go for him.”2

Motton showed up for work in the Arizona Instructional League and learned from some teammates that the Orioles had paid $12,000 to select him. “The manager said I couldn’t suit up because I was no longer Cubs property,” Motton recalled. “I had mixed emotions. I figured it would be easier to break into the Cubs’ outfield.”3

In 1963, Motton batted .333 to finish second in the California League batting race, helping the Stockton Ports win the title. He hit 10 home runs and stole 22 bases, walked 90 times, and notched 90 RBIs. His plan was to continue his development in the Peninsula Winter League, but he ended up being drafted into the Army. During his two-year hitch, he was mainly stationed in Fairbanks, Alaska.

Disappointed at having to postpone his pursuit of a professional career, Motton nonetheless managed to stay sharp playing a pretty good band of ball in the service. In the summer of 1964, he joined the Goldpanners of the Alaska Baseball League, a college players’ circuit, for 16 games, batting .286. Still, he’d missed almost two seasons by the time the Army let him go home early to pursue his career. He joined the Fox Cities (Appleton, Wisconsin) Foxes of the Class A Midwest League late in 1965, making the All-Star team despite his abbreviated stint with a .275, six-homer performance in 44 games. Then he was off to the Florida Instructional League, where his .336 average topped the circuit as the Orioles’ entry won the pennant under Vern Hoscheit. Finally, in February, he played for the La Guaira Sharks in the Venezuelan League, helping them win their second consecutive title.

Motton began 1966 with the Double-A Elmira Pioneers. Hitting .287 with 11 home runs and 62 RBIs in 112 games, he was challenging for the Triple Crown before his call-up to the Triple-A Rochester Red Wings in mid-August. Motton hit .337 to help Rochester win the International League pennant on the season’s last day. (For his performance at Elmira, he lost Eastern League MVP honors by one vote to Howie Bedell of the York White Roses.)

Motton started the 1967 season with Rochester. He was briefly derailed by a botched hit -and-run play early in the season. He dived head-first into second base and was knocked unconscious when his chin struck the knee of the opposing shortstop. Motton needed eight stitches to close the wound, and spent two nights in the hospital with a mild concussion. When he returned to the Rochester team he was out of the lineup for six days. “And the first time back I felt a little dizzy,” he said. “I was a little gun shy at the plate, afraid I couldn’t get out of the way of the ball if I had to. But gradually, the dizziness disappeared.”4

With his average up to .336 on the Fourth of July, Motton was called up to the Orioles when they traded pitcher Steve Barber to the Yankees. In a little less than a month with the big club, Motton collected his first big-league hit (off the Chicago White Sox’s Jim O’Toole at Comiskey Park) and his first home run (off the Red Sox’s Galen Cisco at Fenway Park), and batted .244 in 17 games. After being sent back down to Rochester, he wound up leading the International League in RBIs with 70 and finished second in the batting race at .323. Motton hit 18 home runs and drew 72 walks. Though a 3-for-24 September dropped his major-league average to .200 for 1967, Motton’s composite .307 mark in the minors since turning pro meant he’d hit himself into the big leagues..

“I’ve always had success in hitting,” Motton said. “Mostly it’s a matter of concentration. I’ve maintained the same batting style that I’ve had since I was 14 and played American Legion ball: closed stance, stand straight up and keep my hands close to my body.”5

In 1968, Motton made Baltimore’s Opening Day roster and got an early-season opportunity when Frank Robinson missed time with the mumps. Motton started 18 consecutive contests, including all but the first game of a 13-and-2 stretch that lifted Baltimore from fifth place to first. The Birds followed that with seven consecutive losses and never regained the division lead.

Motton’s most memorable hits in his rookie campaign came off the bench. On May 15 and 17 he tied a major-league record by hitting home runs in consecutive pinch-hit at bats. The hits, off Detroit’s Jon Warden and Cleveland’s Hal Kurtz, both came with two runners on base. In late August Motton went on the disabled list for a few weeks after pulling a hamstring. He finished his freshman season with just a .198 batting average in 83 games, but demonstrated good patience at the plate and cracked eight home runs in 217 at bats.

Elrod Hendricks and Motton were roommates at that time, and when the Orioles catcher looked back on his quarter-century-plus with the Orioles, he recalled Motton as the worst driver of all. “I remember Luis Tiant telling him, ‘Please, Mr. Motton, watch the road. Please, Mr. Motton, you’re going to get me keeled,’ ” Hendricks told the Baltimore Sun. “But he drove me around for two years. I can’t complain too much.”6

The Orioles were a dynasty for Earl Weaver’s first three seasons as manager, 1969-1971, winning 318 regular-season games and a trio of pennants. For Motton, however, it was something of a bittersweet time as he started just 46 games in those three years, after starting 53 times as a rookie. “We’re winning. That’s the only good thing about sitting on the bench here,” he observed at the time. “With a club like this, you can make more money because we get in the playoffs and the World Series.”7

Weaver empathized with Motton’s desire to play more and with the difficulties of coming off the bench, but had three very good reasons for his lineup selection. “In left field, we’ve got Donny (Buford), an outstanding leadoff hitter,” Weaver said. “Paulie (Blair) is an outstanding center fielder, and Frank (Robinson) is an outstanding everything in right, so Curt has to settle for being our best pinch-hitter.”8

For Motton, it wasn’t that easy. He confessed feeling depressed about being unable to force his way into the lineup. “I thought maybe they could do as well with 24 men as with 25,” he said. “They didn’t need me that much. They were winning with the same eight guys.”9 After he managed just one hit in his first 10 pinch-hit attempts in 1969, Motton’s spot on the roster was in jeopardy. Weaver reminded him, “You’re not here on a pass,” and Motton got the message. “What it boiled down to was that if I didn’t start doing better, Earl was going to make some changes and get another pinch-hitter.”10 Crediting a gradual mental adjustment, Motton batted .389 (7-for-18) as a pinch-hitter the rest of the way, including game-winning homers off left-handers Jim Rooker and Paul Lindblad to beat the Kansas City Royals and Oakland Athletics, respectively, in August. Overall, Motton reached base 13 out of 33 times off the bench to rank as one of the league’s best reserves. In 56 games overall, he contributed to Baltimore’s first-place finish by hitting .303 with a .398 on-base percentage and a slugging average of .573.

Arguably the biggest hit of Motton’s major-league career delivered a crucial victory over the Minnesota Twins in October’s inaugural American League Championship Series. After a thrilling 12-inning comeback victory in the series opener, Baltimore came precariously close to dropping the second game before the series shifted to Minnesota. Deadlocked in a scoreless tie in the bottom of the 11th, the Twins called on left-handed relief ace Ron Perranoski to face Elrod Hendricks with two on and two outs. Weaver countered by sending up Motton, who set up the Orioles’ eventual sweep with a game-winning single. “The pitch was away on the outer part of the plate,” Motton recalled. “And I did something I rarely did – I hit it to right field. I just wanted to make good contact and hoped things would work out.”11

Motton grounded out in his only World Series plate appearance as Baltimore suffered a stunning upset loss to the New York Mets, and wasn’t surprised at all when neither the Royals nor the Pilots chose him in the expansion draft that off-season. “No one had seen me play enough,” he observed.12

He went to Puerto Rico that winter to join the Santurce club, managed by Frank Robinson. Motton viewed it as an opportunity to get some opportunities against right-handed pitchers, after just 40 such at bats during the 1969 season. He saw enough curves and sliders from right-handers to consider it a worthwhile journey, but wound up on the disabled list after straining a tendon in his left hand on a checked swing. The pain was so intense that he couldn’t even squeeze a tube of toothpaste. Santurce dealt him to the Caguas team, but Motton came back home instead and got married. He and his wife, Jackie, moved to Baltimore full time about a year later and welcomed daughter Simone Nicole in early 1971. Motton remained in the area even after the couple divorced.

In 1970, Motton started only five games through the end of July, and saw his overall numbers slip to a .226 batting average with a .393 slugging mark. He made the most of his 19 hits though, collecting 19 RBIs thanks to a .346 mark with runners in scoring position. “The thing that kept me keyed up and always ready was the way Earl (Weaver) used me,” Motton said. “He almost always used me when it was a close ballgame. If I did my job, I was going to make a positive contribution to the ballclub.”13

Motton was known as Cuz to his teammates due to his friendly manner. The nickname was also fitting because he’d found his baseball niche with the Orioles in Baltimore. Broadcaster Roy Firestone, who was the Orioles’ spring-training batboy in 1970, recalled, “He was country, sweet, so funny, and had a down-home wisdom to him that made everyone around him especially (Paul) Blair, (Don) Buford, and (Dave) May love him to death.14

“Guys like Curt made us more of a complete team,” recalled Hall of Fame pitcher Jim Palmer.15 The Orioles romped through October to win the 1970 ALCS over the Twins and the World Series against the Cincinnati Reds with such relative ease that Motton did not see action in a single postseason game. One of his Louisville Sluggers wound up in the Hall of Fame, though, after teammate Dave McNally borrowed it in Game Three and belted the only grand slam hit by a pitcher in the history of the Fall Classic.

Motton’s playing time with the Orioles became even scarcer in 1971. It started when he suffered through a difficult spring training after being bothered by a bad heel. Though he insisted he didn’t worry because he knew Weaver remained confident in him, Motton had just 14 at bats with one hit in the Orioles’ first 84 games. Finally, on July 10, Weaver started him in both games of a doubleheader against the Cleveland Indians at Memorial Stadium. Motton ripped a grand slam off Sam McDowell in the opener and a two-run homer off Mike Paul for the Orioles’ only runs in the nightcap. Nevertheless, he finished the season hitting just .189 in 53 at bats, though he did hammer four home runs.

When the Orioles needed him in the playoffs against Oakland, Motton was ready. Baltimore trailed Vida Blue, that year’s Most Valuable Player and Cy Young Award winner, by 3-2 with two on and two out in the bottom of the seventh in the ALCS opener. Motton stepped up as a pinch-hitter for pitcher Dave McNally, worked the count to three balls and a strike, and ripped a game-tying double to the left-field corner.

Baltimore went on to win the game, sweep the series, and earn a third straight trip to the World Series, but Motton did not get into any games as the Orioles lost a seven-game classic to his old friend Willie Stargell and the Pittsburgh Pirates. After Baltimore dealt right fielder Frank Robinson to the Dodgers in December, Motton figured he’d at least be back again in 1972 as a pinch-hitter. However, one week after the Robinson trade, Motton was sent to the Milwaukee Brewers for cash and a player to be named later. The Orioles received hard-throwing reliever Bob Reynolds in spring training.

Milwaukee provided even fewer chances for Motton to strut his stuff. Despite a pinch-hit homer in his first Brewers at bat, he was traded to the California Angels for reliever Archie Reynolds after getting only seven plate appearances in six games. The Angels sent him down to Triple-A Salt Lake City, where Motton mashed Pacific Coast League pitching for five homers and a .320 batting average in 26 contests before earning a return ticket to the majors. He got into 42 games with the Angels, but made only 44 plate appearances as he was often employed as a pinch-runner or pinch-hitter. He batted just .154.

Motton began the 1973 season back at Salt Lake City, but he didn’t hit and was loaned to the Oakland A’s Southern League affiliate in Birmingham. The Angels released him in mid-July, and he was re-signed by the Orioles two days later. Baltimore sent him to Rochester to play himself into shape, but Motton continued to struggle. His eyes and reflexes were as good as they were in 1967, when he played himself into the majors for the first time, but his timing was off from half a decade of playing so sparingly. In 92 minor-league games in 1973, Motton batted just .199, though he did hit 12 home runs in 236 at bats. The Orioles called him up for the last two weeks of the season and he got into four games, even hitting a three-run homer against the Indians in the season finale.

Motton spent 1974 as a player/coach with Rochester under Joe Altobelli. He batted.300 and drew 58 walks in part-time action for an amazing .462 on-base percentage. The Orioles brought him up late in the year, but he went hitless in the last ten plate appearances of his professional career.

After retiring, Motton got into real estate and insurance sales, but he returned to baseball in 1981 as a minor-league instructor with the San Francisco Giants, where his best friend in baseball, Frank Robinson, was managing. After five years in that position, Motton returned to Rochester and was on the Red Wings’ coaching staff from 1986 through 1988, then was Baltimore’s first-base coach from 1989 through 1991 when Robinson took over as the Orioles’ skipper. Motton remained with the organization for more than a decade after that as a special assignment scout, traveling to the Dominican Republic, Venezuela, and across the US.

Motton remarried in 1993, wedding law-enforcement veteran Marti Franklin-Motton, and the couple settled in Parkton, Maryland, in northern Baltimore County. He participated in fantasy camps, became a regular at Orioles Fan Fest, appeared at autograph signings and taught baseball clinics for youngsters on behalf of Virginia’s Diamond Dream Foundation. “People in Baltimore remember me because I was part of those (great) ballclubs,” he said.16

Motton became a grandfather early in the new millennium when his daughter, Simone Nicole, gave birth to a son, Tyree. In 2006, he was inducted into the Rochester Red Wings Hall of Fame. He was diagnosed with stomach cancer shortly thereafter and died at the age of 69 on January 21, 2010. He is buried in Druid Ridge Cemetery in Pikesville, Maryland.

Author’s note

Thanks to Curt Motton, his widow, Marti Franklin-Motton, and the Motton family for their e-mail correspondence.

Notes

1 Ralph Ray, “Who Needs Speed? Not With Orioles Arsenal,” The Sporting News, October 16, 1971, 15.

2 Doug Brown, “Orioles Chirping Over May and Motton,” The Sporting News, May 25, 1968, 8.

3 Brown, “Orioles Chirping.”

4 Al C.Weber, “May, Motton Spell Muscle For Wings,” The Sporting News, June 3, 1967, 35.

5 Larry Whiteside, “Can Motton Crash Brewer Lineup?” The Sporting News, January 8, 1972, 36.

6 Tom Keegan, “Elrod Gives the Nod to Worst, Best and Rest,” Baltimore Sun, May 25, 1994.

7 Doug Brown, “Motton Sees Some Things Right In Winter Troubles,” The Sporting News, February 7, 1970, 32.

8 Doug Brown, “Motton’s Timely Touch In Clutch Hitting Turns On Orioles,” The Sporting News, September 13, 1969, 4.

9 Brown, “Motton’s Timely Touch.”

10 Brown, “Motton’s Timely Touch.”

11 Jeff Seidel, Where Have You Gone? Baltmore Orioles (Sporting Publishing LLC, 2006), 82.

12 Brown, “Motton’s Timely Touch.”

13 Seidel, Where Have You Gone, 82.

14 Roy Firestone, post on www.orioleshangout.com, January 23, 2010.

15 Obituary, Baltimore Sun, January 22, 2010.

16 Seidel, Where Have You Gone, 82.

Full Name

Curtell Howard Motton

Born

September 24, 1940 at Darnell, LA (USA)

Died

January 21, 2010 at Parkton, MD (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.