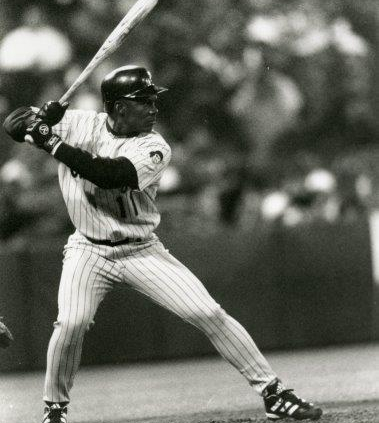

José Guillén

Throughout much of his major-league playing career, he appeared to be a polarizing fusion of skills. One was a rare talent for hitting baseballs. The other, at times, seemed like an unerring instinct for finding the midst of controversy, great or small. José Manuel Guillén, a right-handed-batting and -throwing outfielder who was capable enough with a bat to produce a .270 batting average, hit 214 home runs, and drive in 887 runs over the course of a 14-year major-league career, was so difficult at times that he bounced around nine different organizations during the span. His baseball career was marked by pronounced highs and a few distinct lows, the latter including implications of use of performance-enhancing drugs in the 2007 Mitchell Report.1

Guillén’s baseball career, however, was never predestined to end in such relative ignominy. In fact, it is a testament to his abilities and drive that he reached such a professional height at all. Born in San Cristobal, Dominican Republic, on May 17, 1976, the boy quickly grew to love the baseball, as did so many of his contemporaries. By the age of 10, playing in undersized shoes on rocky, dirt fields, and against the objections of his father, who labored in a bottle-making factory in town, José grew fixated on the game. Erzo Guillén thought in practical terms, that the boy should learn to earn a realistic living on the island. His mother, Modesta, disagreed, and actually paid for his formal baseball league team uniform. The league had some equipment donated by some local scouts and “leftovers from the big leaguers who grew up there (DR) and never forgot it.”2 Guillén had no spikes, and did not even own a glove until Raul Mondesi gave him one when the boy was 15. “My mom bought me my first bat when I was 12. I was so proud.”3

The boy had talent, but one unnamed Texas Rangers scout told him, “You’re too skinny. You’ll never make it.”4 Guillén got his measure of psychological revenge at age 18 (August 19, 1993), however, when he signed with the Pittsburgh Pirates for $2,000 and reported to their Gulf Coast League team for the 1994 season. By 1996, batting .322 for the Lynchburg Hillcats, he was named Most Valuable Player in the Carolina League, and on April 1, 1997, he made his major-league debut against the San Francisco Giants. Despite his 0-for-4 day at the plate, he went on to post a .267 batting average in 143 games. That performance earned him a spot on the 1997 Topps All-Star Rookie Team.

By mid-1999, though, Guillén ’s performance had declined to the point that the Pirates demoted him to Triple-A Nashville. Though he regained his stroke and batted.333 for more than a month in the Pacific Coast League, the Pirates still traded him and Jeff Sparks to the Tampa Bay Devil Rays for Joe Oliver and Humberto Cota. Over the next two years, Guillén never batted over .275, and on November 27, 2001, he was given his outright release.

Less than a month later, on December 18, the Arizona Diamondbacks signed Guillén for the 2002 campaign, but released him on July 22. The Rockies then signed Guillén, but then released him three days later, on August 1. From that figurative closed door came an open window in Cincinnati. The Reds signed him on August 20 and were rewarded in 2003 with Guillén’s best performance to date. He slashed a line of .337/.385/.629 in 91 games that year. The Reds, not convinced that Guillén could sustain that pace, sold “high” and traded him to Oakland for three players, including future rotation anchor Aaron Harang.

In a new league and new city, Guillén continued to hit well and finished the year with 31 homers and a .311 batting average. These were the Oakland Athletics, renowned for low payroll and a collective willingness to take risks on younger players,5 so rather than re-sign the outfielder to a long contract and elevated money, they cut salary by releasing him on October 30. The Anaheim Angels signed the free agent on December 20, 2003, and he repaid their faith by driving in 104 runs in 2004.

It was in Anaheim that the first controversy arose around Guillén. During the eighth inning of a late-season game against Oakland, Angels manager Mike Scioscia removed his outfielder for a pinch-runner. “Guillén walked off the field slowly, then flung his helmet toward the end of the dugout where Scioscia was standing. He then walked to the opposite end of the dugout and, after entering it, he threw his glove against the dugout wall.”6 The next day, Sunday, the Angels suspended Guillén for the rest of the season. Interestingly, the incident wasn’t the first outburst; the outfielder “went on a profanity-laced tirade after being beaned in a game at Toronto in May, complaining that his teammates weren’t retaliating for him.”7 It was a difficult denouement to what had been Guillén’s best season on the diamond.

The die was cast, though, and on November 19 the Angels traded Guillén to the Montreal Expos – in the process of becoming the Washington Nationals – for Maicer Izturis and Juan Rivera. The Nationals’ arrival in Washington stirred tremendous excitement in the normally jaded city. A new ballpark on the Potomac River was in the works, but it wouldn’t be ready for three years at the earliest. The team acquired Guillén’s lower-cost bat8 as part of a short-term effort to sustain fan enthusiasm during the transition. As had become his modus operandi, the outfielder responded well to the change of venue, playing in 148 games and slugging 24 home runs and 32 doubles.

Naturally there were squabbles. The most notable occurred during a three-game series in Anaheim, Guillén’s first visit since his suspension the previous year. During the second game of the series, when managers Frank Robinson and Mike Scioscia engaged in an argument over a separate, on-field issue, Guillén could not contain himself. “Sitting in the visiting clubhouse Wednesday night … Guillén let loose on Scioscia. “I don’t got truly no respect for him anymore because I’m still hurt from what happened last year. I don’t want to make all these comments, but Mike Scioscia, to me, is like a piece of garbage. I don’t really care. I don’t care if I get in trouble. He can go to hell. We’ve got to move on. I don’t got no respect for him. … I want to beat this team so bad. I can never get over about what happened last year. It’s something I’m never going to forget. Any time I play that team, Mike Scioscia’s managing, it’s always going to be personal to me.”9

Also in keeping with Guillén’s history, the next year, 2006, saw a decline in his offensive output. This time, however, there was a medical reason. In July, after only 69 games, he was diagnosed with a torn ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) in his right elbow. Dr. James Andrews performed reconstructive surgery on the elbow on July 25, and sent Guillén to his home in Miami, Florida, for physical therapy.10 For what was likely a combination of reasons, the Nationals did not re-sign Guillén, instead offering him salary arbitration, and he was granted free agency on October 30.

He was not out of work for long. Searching for a “corner outfielder with power,” the Seattle Mariners signed Guillén on December 4.11 Guillén signed for a personal high salary of $5 million, with a $9 million option for the next year. The newest Mariner, playing alongside quiet professionals like Ichiro Suzuki and Adrian Beltre, produced as expected, hitting .290 and driving in 99 runs. By this time, he’d also married his girlfriend, Yamel, also from the Dominican Republic and with whom he fathered sons José Jr. and José Manuel.

In what might have felt like an annual rite, Guillén was again designated a free agent on October 30, able to sell his services to the highest bidder. Complicating this, however, was the first hint of his involvement with performance-enhancing substances. On November 6, 2007, Mark Fainaru-Wada and Lance Williams, San Francisco Chronicle staff writers, broke a report that Guillén “ordered more than $19,000 worth of drugs from the (Palm Beach Rejuvenation Center) between May 2002 and June 2005.”12 ESPN’s Jerry Crasnick followed this up by speculating about the potential effect of the accusations on Guillén’s future. “Kansas City GM Dayton Moore was asked if the Royals might rethink their interest in the free-agent outfielder. No, Moore replied – sort of. And he was only comfortable addressing the topic in general terms. “Unfortunately, there was a period of time in baseball that we all know now that circumstances like this were occurring,” Moore told the Kansas City Star. “I think you have to put it into perspective to that particular period of time even if it is a negative mark on the game.”13

The Royals pressed forward, aware of the potential pitfall, and signed Guillén to a three-year contract worth $36 million. He was suspended for the first 15 days of the season for violating Major League Baseball’s drug policy,14 but that punishment was rescinded following agreement between the Players Association and MLB regarding changes to the entire drug-testing program. Despite the chaos, Guillén still managed 20 homers and 97 RBIs in his first year with the team. Not one to enjoy tranquility, he again made the news on August 26 when he got into a row with a fan at a game in Arlington, Texas. Guillén reportedly yelled profanities and made gestures at a fan who had been loudly accusing the player of lack of effort (even though Guillén had singled in his previous time at bat). After his teammates restrained him, and the fan was removed by security, the game resumed without incident.

That winter, Guillén played for the Dominican Republic in the 2009 World Baseball Classic, but managed only one hit in 12 at-bats. The normally strong Dominican team finished the tournament with a 1-2 record and an early return home. On July 22, 2009, Guillén tore a ligament in his right knee while tying on a shin guard preparing to come to bat against the Los Angeles Angels, and he missed the next 10 weeks, returning for games on September 1 and 2 to close out his season.

Guillén batted only .242 over those 81 games in 2009, and even though he got his 1,500th hit on May 21, 2010, the Royals sent him to the San Francisco Giants on August 12 for cash and a minor leaguer. Almost immediately after joining the team, Major League Baseball restricted him from postseason eligibility due to his appearance in the Mitchell Report.15 Guillén’s final game came on October 3, 2010, but the shadow of illegal drugs kept him from ever suiting up again.

The New York Daily News summarized the recurring case against Guillén:

“… José Guillén only put himself and his wife in a world of legal hurt when the Giants’ outfielder allegedly arranged for a shipment of nearly 50 pre-loaded syringes of human growth hormone to be sent to his San Francisco address in September, while his team was clawing its way to a playoff berth. … (DEA) agents, who were monitoring the activities of the suspected supplier, intercepted the package when it was sent to the Giants’ outfielder to the attention of Yamel Guillén – José Guillén’s wife, who also goes by Yamel Acevedo.

Federal agents contacted Major League Baseball’s Department of Investigation about the shipment and the DOI, according to sources, continues to investigate the matter and whether anyone else in baseball might have been involved, especially since Guillén has a history of acquiring HGH and steroids. … After the DEA tracked the September package, believed to have been sent from Miami through the San Francisco Airport, agents then arranged a controlled delivery to the home of Guillén, where Yamel Guillén signed for the package. Once she penned her signature, DEA agents identified themselves and Yamel Guillén consented to a search. She is believed to have left the country in recent weeks, returning to the Dominican Republic.”16

On November 1, 2010, José Guillén again became a free agent, cut loose by the Giants, his 10th major-league organization. In 2012, Enrique Rojas of ESPNDeportes reported that Guillén was working out back at home in the Dominican Republic with the intention of making a comeback at age 36.17 Rojas noted that Guillén had “apparently drawn interest from at least a couple teams,” but the attempt never really gained momentum.

Last revised: October 29, 2022

Notes

1 George Mitchell, Report to the Commissioner of Baseball of an Independent Investigation into the Illegal Use of Steroids and Other Performance Enhancing Substances by Players in Major League Baseball, 2007.

2 Paul Daugherty, “Ode to an Act of Kindness,” Cincinnati Enquirer, June 22, 2003 (online: reds.enquirer.com/2003/06/22/wwwred1doc22.html.Accessed October 1, 2017).

3 Daugherty.

4 Daugherty.

5 Michael Lewis, Moneyball (New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 2003).

6 Jim Mone, “Angels Suspend Guillén Without Pay for Rest of Season,” USA Today, September 28, 2004 (online: usatoday30.usatoday.com/sports/baseball/al/angels/2004-09-26-Guillén -suspension_x.htm#).

7 Mone.

8 The league average was just under $2.7 million (cbssports.com/mlb/salaries/avgsalaries), while Guillén’s contract was for only $3.5 million (baseball-reference.com/players/g/guilljo01.shtml).

9 Barry Svrluga, “Sparkling Debut for Nats’ Drese,” Washington Post, June 16, 2005 (online at washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2005/06/16/AR2005061600099.html).

10 “Nationals Right Fielder Jose Guillén Has Successful UCL Reconstruction Surgery on Right Elbow,” online at washington.nationals.mlb.com/news/press_releases/press_release.jsp?ymd=20060725&content_id=1574471&vkey=pr_was&fext=.jsp&c_id=was.

11 Corey Brock, “Mariners Targeting Ex-Nat Guillén,” MLB.com, December 2, 2006 (online at m.mariners.mlb.com/news/article/1749651//).

12 Mark Fainaru-Wada and Lance Williams, “Baseball’s Jose Guillén, Matt Williams Bought Steroids From Clinic,” San Francisco Chronicle, November 6, 2007 (online at sfgate.com/sports/article/Baseball-s-Jose-Guillén-Matt-Williams-bought-3234893.php).

13 Jerry Crasnick, “Clubs at Mercy of Circumstances Beyond Their Control,” ESPN.com, November 23, 2007 (online at espn.com/mlb/hotstove07/columns/story?columnist=crasnick_jerry&id=3122788).

14 Dick Kaegel, “Royals Slugger Guillén Suspended,” MLB.royals.com, December 6, 2007 (online at m.royals.mlb.com/news/article/2320510).

15 Michael Schmidt, “Giants’ José Guillén Linked to Drug Investigation,” New York Times, October 28, 2010 (online at nytimes.com/2010/10/29/sports/baseball/29guillen.html).

16 Teri Thompson, “Probe of Giants OF Guillen deepens,” New York Daily News, November 14, 2010 (online at nydailynews.com/sports/baseball/dea-agents-intercepted-hgh-package-attention-giants-jose-guillen-wife-source-article-1.451054).

17 ”Jose Guillen,” NBC Sports.com. https://www.nbcsports.com/edge/baseball/mlb/player/16320/jose-guillen

Full Name

Jose Manuel Guillen

Born

May 17, 1976 at San Cristobal, San Cristobal (D.R.)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.