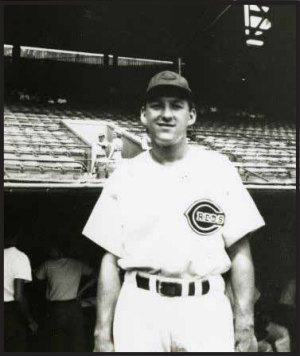

Dick Sipek

Being able to hear the sounds of the game is important to a baseball player, particularly to an outfielder. Hearing the distinctive sound of bat meeting ball enables the fielder to be off at the crack of the bat, getting a jump on the ball, and racing to the spot where he can catch the ball for an out. Hearing a teammate yell, “I’ve got it!” gives needed guidance when a ball is hit between two or more fielders. Hearing the approaching footsteps of a teammate when two outfielders are going after the same fly ball may prevent a costly collision. A player with normal hearing can receive oral instructions from managers and coaches. He can hear the umpire call balls and strikes. He can hear the thud of ball against glove and the sound of a baserunner’s foot touching the base. Dick Sipek heard none of these things. He never heard the roar of the crowd, or the umpire cry, “Play ball!” Yet with a passion for the game he loved and a determination not to be deterred by his deafness, Sipek carved out a successful career in professional baseball, including one season in the major leagues.

Richard Francis Sipek was born in Chicago on January 16 1923, the son of Emily (Piskac) Sipek and John Sipek. During his early childhood the family lived in the household of his widowed maternal grandfather, who had immigrated in 1899 from what is now the Czech Republic but was then a part of Austria-Hungary. Emily’s father, Frank, worked as a clerk at City Hall. At the time of the 1930 census, John Sipek’s occupation was listed as “operator, tracings.” The family lived on Komensky Avenue in Chicago.

At the age of 5, young Richard became deaf. Sources disagree on the cause of his deafness. Some say he lost his hearing in an accident.1 Another source attributed the hearing loss to an illness.2 It is likely that neither version is correct. His deafness may have been genetic. His parents could have unknowingly been carriers of autosomal recessive genes. Support for this possibility is provided by the fact that two of Sipek’s three children and three grandchildren also were deaf. The fact that Sipek was not born deaf does not mean the deafness was not genetic. Some inherited hearing loss in children is not present at birth but develops in the early years.3 Sipek himself could shed little light on the matter, claiming, “My mother never did tell me what caused my hearing loss.”4 Perhaps she didn’t tell him because she didn’t know.

The hearing loss was extreme, but not complete. He could still faintly hear very loud noises. There is no definition of what is considered legally deaf, but the medical profession generally considers anyone deaf who cannot hear well enough to rely on their hearing to process speech and language. Under that definition Sipek certainly qualifies as deaf. Frequently, he is referred to as a deaf-mute, implying that he could neither hear nor speak. In the case of Sipek that does not apply. His vocal organs were unimpeded, and he learned to talk before he lost his hearing.

In the days before special education for students with handicaps or disabilities, the lad’s deafness caused him to struggle in school, so in 1932 his parents sent the 9-year-old boy to the Illinois School for the Deaf in Jacksonville. With the guidance of specially trained teachers, Richard (now called Dick) blossomed academically. He became an honor student and eventually president of the senior class.

Dick was fortunate that the school assigned as his housefather Luther “Dummy” Taylor, the greatest deaf pitcher in the history of baseball. Taylor had won 21 games for the New York Giants in 1904 and compiled 116 wins in his major-league career. Taylor took the youngster under his wing and encouraged his athletic pursuits. Young Sipek responded by excelling in basketball and football, achieving all-state honors in the latter sport. However, it was in baseball that Taylor saw the brightest future for his protégé. The ex-moundsman wanted Sipek to be a pitcher, but Sipek wanted to play every day and elected to become an outfielder.5 Envisioning a professional baseball career for the young man, Taylor wrote to the New York Giants and the Cincinnati Reds, asking them to send a scout to evaluate Sipek. The Giants declined the invitation, but the response from Cincinnati was quite different. Warren Giles, general manager of the Reds, said Taylor’s opinion was good enough for him. Without ever seeing Sipek play, solely on Taylor’s recommendation, the Reds signed the young outfielder to a professional contract.6

In 1943 the Reds sent the 20-year-old left-handed hitter to their Birmingham affiliate in the Class A1 Southern Association. In turn the Barons farmed him out to Erwin, Tennessee, in the Class D Appalachian League. Sipek tore up the league, hitting .424 in 37 games until the Barons called him back up to Birmingham. The 5-foot-9, 170-pounder continued hitting at a torrid pace — .336 in the remainder of 1943. Between games of a Fourth of July doubleheader at Nashville’s Sulphur Dell, the clubs arranged for a 75-yard dash among their best speedsters. Sipek finished third in the sprint.7 According to Barons manager Johnny Riddle,Sipek, despite his deafness, never missed a sign.8 The fact that he couldn’t hear the crack of the bat to tell the direction of fly balls seemed not to be a deterrent. He never misjudged a fly ball, whether in daylight or under the lights. At the end of the season, Birmingham fans voted Sipek the most popular Baron.

The 1944 season was another productive one for Sipek. He received his diploma from the Illinois School for the Deaf on June 1. Because of his high scholastic average, the school had allowed him to miss the last few weeks of his senior year in order to play baseball in Birmingham. For graduation presents his Baron teammates presented him a travel kit and a $100 war bond.9 He hit .319 for Birmingham in 1944, earning him a promotion to the Cincinnati roster at the end of the Southern Association season. He did not appear in any games for the Reds after his elevation, but he was a big leaguer — one of ten outfielders who would be evaluated during spring training, 1945.

During wartime there was no Grapefruit League or Cactus League for spring training. Railroad trains were needed to transport troops and war supplies, not to haul baseball players and equipment. Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis and Joseph B. Eastman, director of the federal Office of Defense Transportation, worked out an agreement. Clubs would be permitted to engage in spring training, but only in sites near their home base. Detroit, Pittsburgh, the two Chicago clubs, and the two clubs based in Ohio would conduct their preseason activities in Indiana. The six clubs formed an informal confederation dubbed the Limestone League. The highlight of the spring for Dick Sipek came when he hit a ninth-inning home run to defeat the Chicago Cubs in an exhibition game before soldiers at Fort Knox, Kentucky, on April 6. He earned himself a spot on the Reds’ Opening Day roster.

Sipek made his major-league debut on April 28, 1945, at the age of 22. Pinch-hitting for catcher Joe Just, he drew a walk in his first game appearance. During the early spring he was used exclusively as a pinch-hitter, usually without much success. His first major-league hit was a pinch-hit RBI single off Dick Barrett at Philadelphia’s Shibe Park on May 16. During the season he appeared in 82 games for the Reds, usually as a pinch-hitter. He played in 31 games in the outfield — 14 in left field and 17 in right. He had a slightly subpar .972 fielding percentage, committing two errors, and he hit .244 for the season, with six doubles and two triples. He drove in 13 runs and scored 14.

Both Sipek and the club had a disappointing season, as the Reds finished in seventh place, 37 games out of the lead. They decided to forget their woes temporarily by having a unique party in their clubhouse on September 18. The previous day they agreed that each player should bring an inexpensive gift for another member of the team, the recipient to be selected by a drawing. Anyone forgetting to bring a gift would be fined $5. When outfielder Dain Clay arrived at the park, Sipek reminded him of the agreement. The players split the fine between Clay and Sipek, charging them $2.50 each. The presents were gag gifts, of course. According to The Sporting News, “a howling good time was had.”10

Sipek made his final major-league appearance on September 29 in a game against the St. Louis Cardinals at Crosley Field. His last major-league time at bat saw him in a familiar pinch-hitting role. He made an out, ending the season and his major-league career.

On March 24, 1946, the Reds optioned Sipek to the Syracuse Chiefs, their affiliate in the Triple-A International League. He hit only .245 for the Chiefs in 1946, and his career was all downhill after that. In 1947 he was in Class A ball at Columbia, South Carolina, in the South Atlantic League. From 1948 through 1951 he played for Reidsville, North Carolina, in the lower-ranking Carolina League (Class C in 1948, Class B thereafter). Sipek fared better in the Carolina League, hitting over .300 in three of his four years in the loop. Perhaps his best day at the plate for the Reidsville Luckies came on May 25, 1949, when he started a ten-run rally against Burlington by hitting a two-run triple in the fourth inning and slamming a two-run homer when he came up for the second time in the inning. In 1951 he suffered a broken collarbone while diving for a fly ball. His baseball playing career was over at the age of 28.

In retirement Sipek lived in Quincy, Illinois, the home town of his wife, the former Betty Ann Schmidt. The daughter of Bertha Lohr and August Schmidt, Betty was born in Quincy in 1924 and attended the Illinois School for the Deaf, where she was a classmate of Sipek, graduating in 1944 The couple had three children, Ronald, Janice, and Nancy. Ronald was born in Quincy in 1950. Ron also attended ISD, where he was an outstanding athlete, quarterbacking the undefeated football team in 1969. He was inducted into the school’s Athletic Hall of Fame in 2009. After graduation he worked at schools for the deaf in Missouri and Mississippi and taught American Sign Language at Quincy University.11

Janice also attended ISD as did her husband and daughter. Nancy did not attend ISD, but apparently carried the recessive gene, as she had a deaf son. Nancy inherited her father’s athletic ability. She was inducted into the Hall of Fame at Quincy University in 2002, for her exploits in field hockey, softball, basketball, and volleyball. As of 2014 she was service coordinator of the Volunteers of America apartments in Jacksonville, which houses persons who are deaf or blind, or have other disabilities.12

For several years Sipek himself worked at Bueters Bakery in Quincy. Then he became custodian at St. Mary School, a Catholic school in the Mississippi River town. He worked a lot with the seventh- and eighth-grade classes, regaling them with stories of his ballplaying days.

He retired in 1988, but often came back to the school to visit and talk baseball with the students and teachers. In 1994, at the age of 70, Sipek appeared at a camp in St. Louis to encourage the hearing-impaired. Signing to an audience of more than 1,000 deaf children, he told them: “Some deaf people are never given a chance because you can’t talk to them. I don’t want people to forget about the deaf. I want deaf people to come up and play.”13

“No matter what it was, he did the best job he could,” said Sharon Terwelp, a longtime teacher at St. Mary. “He truly was a treasure.”14 Sipek’s comment was, “I was motivated and I showed them the deaf can do it. No matter if I can’t hear or I’m hard of hearing. It doesn’t make any difference. I can do it.”15

Sipek’s advocacy for the deaf can be illustrated by an incident that occurred during his retirement years. He was playing in a golf tournament at a convention for the deaf, when another golfer pointed him out and signed that he was the last deaf player in professional baseball. Afterward Sipek confronted the man in the clubhouse and told him he didn’t want to be identified as the last deaf player. He wanted to see another deaf player reach the major leagues.16

Sipek died at Blessing Hospital in Quincy on July 17, 2005, at the age of 82. Survivors included his wife, Betty; son, Ron; and daughters, Janice (Mrs. James Birchall) and Nancy (Mrs. John Harper). He was buried in Quincy’s Calvary Cemetery, near the banks of the Mississippi.

Richard Francis “Dick” Sipek was not a great baseball player, but he was most assuredly a great influence on the lives of thousands of young people.

Notes

1 fookembug.wordpress.com and Quincy Herald-Whig, July 19, 2005.

2 The Sporting News, October 14, 1943.

4 Quincy Herald-Whig, July 19, 2005.

5 The Sporting News, October 14, 1943.

6 Ibid.

7 The Sporting News, July 15, 1943.

8 The Sporting News, October 14, 1943.

9 The Sporting News, June 8, 1944.

10 The Sporting News, September 27, 1945.

13 The Sporting News, May 2, 1994.

14 Quincy Herald-Whig, July 19, 2005.

15 Ibid.

16 Rick Swaine, Beating the Break: Major League Ballplayers Who Overcame Disabilities (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2004), 118. Curtis Pride became the next deaf player in the major leagues, debuting with Montreal in 1993 and playing in parts of 11 major-league seasons through 2006.

Full Name

Richard Francis Sipek

Born

January 16, 1923 at Chicago, IL (USA)

Died

July 17, 2005 at Quincy, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.