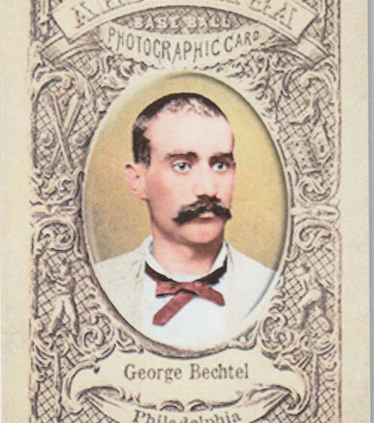

George Bechtel

Before it came to a premature halt, the career of 1870s pitcher-turned-outfielder George Bechtel was not without distinction. Bechtel was a member of major league baseball’s first championship team, the 1871 Philadelphia Athletics of the National Association. Four seasons later, he and teammate Bill Craver became the first players to have their contracts transferred by one major league club to another. But Bechtel’s most noteworthy distinction is a shameful one. In 1876, he was accused of game-fixing and became the first player permanently expelled from the majors. After his application for reinstatement was denied by the fledgling National League, Bechtel spent the ensuing four-plus decades away from the game, working quietly as a blacksmith until his death in April 1921. His life story follows.

Before it came to a premature halt, the career of 1870s pitcher-turned-outfielder George Bechtel was not without distinction. Bechtel was a member of major league baseball’s first championship team, the 1871 Philadelphia Athletics of the National Association. Four seasons later, he and teammate Bill Craver became the first players to have their contracts transferred by one major league club to another. But Bechtel’s most noteworthy distinction is a shameful one. In 1876, he was accused of game-fixing and became the first player permanently expelled from the majors. After his application for reinstatement was denied by the fledgling National League, Bechtel spent the ensuing four-plus decades away from the game, working quietly as a blacksmith until his death in April 1921. His life story follows.

George W. Bechtel was born in Philadelphia on September 2, 1848. He and his twin sister Mary Emma were the oldest of the six children1 born to Pennsylvania native William P. Bechtel (1821-1903), a Union Army veteran later identified in census reports as a “stationary engineer,” and his New Jersey-born wife Martha (1826-1898). Apart from being raised in a Protestant household and attaining literacy, little is known of George’s youth. But by the mid-1860s, he was working locally as a teenage blacksmith and playing baseball on Philadelphia sandlots. Tall for the time and lanky (5-feet-11, 165 pounds), the presumably right-handed Bechtel2 was originally a pitcher, making underhand deliveries for the amateur West Philadelphia (1866-1867) and Geary (1868) clubs.3 By 1869, he had moved up to the faster Keystones nine. Bechtel remained a pitcher for the Keystones during the 1870 season, but also saw action in left field for the Athletics, a rival Philadelphia club.4

The 1871 season brought the first major league circuit to the fore. The National Association was home to fully professional baseball clubs situated in New York, Philadelphia, Boston, Chicago, and other American cities east of the Mississippi River. The class of the new circuit was the Philadelphia Athletics. Paced by standouts like outfielder Levi Meyerle (.492 BA), catcher Fergy Malone (.343), second baseman Al Reach (.353), and pitcher-manager Dick McBride (18-5), the A’s posted a sterling 21-7 (.750) record and captured the first NA flag. Making a significant contribution to the pennant-winning effort was the club’s 22-year-old semi-regular left fielder, George Bechtel. In 20 games, Bechtel batted a robust .351 (33-for-94), with 21 RBIs and 24 runs scored. He also served as emergency hurler when McBride was unable to enter the box. For a September 3 contest against the New York Mutuals, “Bechtel was substituted in his position and pitched with great effect,” reported the Philadelphia Inquirer on the A’s 9-8 victory.5 He was drubbed in two subsequent outings, however, and ended the season with an unsightly 7.96 ERA in 26 innings pitched.

Despite the late-season pitching setbacks, Bechtel had proved a stalwart member of a championship Philadelphia club. After the season, there was considerable interest in his services among National Association competitors. Along with open gambling on games,6 roster instability was a constant problem in the NA, and like other talents, Bechtel did not remain with one club for long. During the off-season, he signed with the New York Mutuals for the upcoming campaign.7

Bechtel’s $1,000 salary was among the lowest on the New York team,8 and the Mutuals’ connection to corrupt Tammany Hall politicos had long tainted the club’s reputation.9 But whether the game-fixing in Bechtel’s future can be traced back to his tenure in New York is shrouded by the passage of time. For the moment, however, his play remained above suspicion. As he had been in Philadelphia, Bechtel was a solid contributor to the Mutuals on offense, batting .300 in 51 games for the third-place (34-20-2, .630) club. But his outfield defense (81 putouts with 4 assists and 20 errors = .810 fielding percentage) was substandard, well beneath the marks of outfield mates Dave Eggler (.917) and John McMullin (.875).

The following season, Bechtel returned to Philadelphia, joining a newly-formed NA club called the White Stockings. Reunited with former mates Levi Meyerle (.349) and Fergy Malone (.290), Bechtel was a regular in the Philadelphia outfield and improved his fielding average to .843 (85 putouts, 12 assists, 18 errors), tops among club gardeners. But his hitting fell off markedly (.244 BA). Still, he contributed a useful 39 RBIs and 53 runs scored to the cause of the second-place (36-17, .679) White Stockings. Occasionally spelling staff leader George Zettlein (36-15), Bechtel went 0-2 in three hurling appearances.

Returning to the White Stockings in 1874, Bechtel’s playing time dropped to 32 games. The cause was likely a .667 fielding percentage (40-6-23), atrocious even by barehanded era norms. But Bechtel’s batting average bounced back to .278, with 34 RBIs and 29 runs scored, and he did helpful spot duty in the box as well, going 1-3 but with a sparkling 1.62 ERA in 39 innings.

Philadelphia began the 1875 season with three NA ball clubs: the established Athletics and White Stockings, plus a new nine, the Centennials. Signing with the newcomer, Bechtel served as pitching mainstay for the Centennials. He threw every inning of the first 14 games, posting a dismal 2-12 (.143) record despite a decent 2.71 ERA. By then, the new Philadelphia franchise was in dire financial straits, pressed on all sides by creditors. On May 26, 1875, the Centennials sold the contracts of Bechtel and manager-shortstop Bill Craver to the Philadelphia Athletics for $1,500. The transfer of the Bechtel/Craver contracts to the A’s is now considered the first inter-club player deal in major league history. The Centennials promptly applied the money to the discharge of club debt and went out of business without ever again taking the field. Meanwhile, the Athletics returned Bechtel to the outfield, where he fielded tolerably (.830 percentage overall) in 35 games. He also chipped in a 3-1 record in four pitching appearances while batting .280 (46-for-164) for the third-place (53-20-4, .726) A’s.

The 1875 season was the National Association finale. In its stead for 1876 was the National League, a new organization spearheaded by Chicago club boss William Hulbert. Prior to the season, “George Bechtel, good natured, ‘easy going Gawgie’ as the people here [in Chicago] term him,” signed with the NL Louisville Grays.10 Assigned the right field spot, Bechtel got off slowly with his new club, his batting average hovering around the .200 mark after 13 games. Bechtel’s next appearance proved his last in a Louisville uniform. On May 30, 1876, he made three fielding errors and went hitless at the plate during a 7-2 loss to the New York Mutuals. In its game account, the criticism of the Louisville Courier-Journal was pointed: “The Louisvilles could not hit [New York pitcher Bobby] Mathews and made many inexcusable errors, Bechtel, especially, in letting three balls to pass him” in right field.11

Shortly thereafter, Louisville got rid of Bechtel – but the grounds for the club’s action are murky. After the May 30 game, Grays manager John Chapman telegraphed the club board of directors, informing them that “Bechtel’s conduct was suspicious, referring to drunkenness,” and adding that Bechtel “had been told before that drunkenness would cause his dismissal” from the club.12 In its June 2 response, the board directed Chapman to solicit Bechtel’s resignation.13 Bechtel refused to quit the team, but he did not continue traveling with the Grays on their East Coast road trip. Instead, he went home.

On June 10, the Grays defeated the Boston Red Stockings, 4-3, behind a solid pitching performance by club ace Jim Devlin. Shortly thereafter, a Boston Globe reporter questioned Louisville skipper Chapman about a rumored attempt to induce Devlin to lose the game. Summoned off the playing field by his manager, Devlin produced a telegram that he had received before game time which read: “Bingham House, Philadelphia, June 10 – We can make $500 if you lose to-day. Tell Chapman, and let me know at once. (signed) Bechtel.” Devlin also produced his wired reply to Bechtel: “I want you to understand that I am not that kind of man. I play ball for the interest of those that hire me. (signed) Devlin.”14

The club’s hand seemingly forced by ensuing newspaper publication of the Bechtel telegram, Louisville secretary George K. Speed sent the following wire to Bechtel at his Camden, New Jersey, residence on June 14: “You are hereby expelled from this Club for drunkenness and failure to comply with your contract. This is the unanimous decision of the Directors.”15

The first stated basis for Bechtel’s expulsion – “drunkenness” – is clear and unremarkable. But the meaning of the cited “failure to comply with your contract” is opaque, as standard contract boilerplate imposed a number of duties on the player, including the commitment to apply his “best efforts” on the field and the like. In his seminal 1995 work on baseball gambling and game-fixing scandals, Daniel E. Ginsburg stated that Bechtel’s work in the May 30 game “made him a much suspected man,” and that the right fielder was terminated by the club for promoting dishonest play.16 And certain contemporary sources concur that Bechtel was punished for crookedness.17 Nevertheless, the dismissal telegram does not explicitly cite this as the cause of Bechtel’s termination.

Whatever its basis, Bechtel did not accept his banishment passively. In a letter to friend and erstwhile teammate Devlin, Bechtel protested his innocence. He had taken no part in the fix attempt and been entirely unaware of the “Bechtel” telegram until it was “published broadcast throughout the country.”18 Perhaps oddly, the Louisville Courier-Journal rose to the banished player’s defense, declaring that “Bechtel has been most unjustly treated in this matter” and excoriating Louisville club directors for jettisoning the accused without affording him a hearing.19 Also in the Bechtel corner was the Chicago Tribune which published an anonymous letter purportedly sent by the real culprits, a trio of New York City pool players who claimed to have concocted the game-fix wire and forged Bechtel’s signature to it.20

With his employment status seemingly in limbo, Bechtel played briefly for an independent pro club in Jackson, Michigan.21 Then in August, he signed with one of his former major league teams, the New York Mutuals.22 But after two mid-August games in center field, the name Bechtel disappeared from Mutuals box scores. No cause for his removal from the lineup was discovered in contemporaneous newsprint – but the suspicion here is that a discreet word from National League secretary Nick Young regarding Bechtel’s eligibility may have precipitated his release.23 In any case, George Bechtel’s career as a major leaguer was now over. In six NA-NL seasons combined, he had batted a respectable .277, with 63 extra-base hits, 165 RBIs, and 216 runs scored in 221 games played. His fielding and pitching logs, however, were less than mediocre. In 30 appearances in the box, Bechtel posted a 7-20 (.259) record, with a poor 3.19 ERA in 243 frames. His fielding was worse, with lackluster work as a spare infielder and pitcher reducing his overall lifetime fielding percentage to under the .800 mark.

At the winter meeting of National League club owners, the New York Mutuals and Philadelphia Athletics were expelled from the circuit for failure to complete their 1876 playing schedules. In spring 1877, a new and unaffiliated Philadelphia Base Ball Club was organized by Fergy Malone. Among the well-known former NL players recruited for the team were George Zettlein, John McMullin, Fred Treacey – and George Bechtel.24 Bechtel made various early season appearances in right field for his new club. But these were in games against League Alliance and independent club competition. The question of whether Bechtel was eligible to play against National League clubs remained unsettled until late June. Then, a letter from NL secretary Young pronounced that Bechtel “was expelled from the League last season” and therefore could not play in games involving NL teams.25 Soon thereafter, Bechtel was either discharged by the Philadelphia club or retired voluntarily in order to devote his attention to a formal petition for reinstatement.

In early August 1877, Bechtel’s petition “to be purged of his expulsion” was denied by the National League Board of Directors.26 Undaunted, he announced his intention to appeal the decision at the NL club owners meeting in December.27 But his timing could not have been worse. Also on the winter meeting agenda was the expulsion of Jim Devlin and three other Louisville Grays players implicated in a bona fide game-fixing scandal during the 1877 season. With NL founder William Hulbert urging that no quarter be given Bechtel, his petition did not stand a chance. Reinstatement was denied.28 The basis for Bechtel’s banishment – whether for termination of his contract by Louisville for drunkenness or for attempted game-fixing or on yet other grounds29 – was not specified by the club owners. But however his contemporaries viewed the situation, today George Bechtel is seen as a game-fixer and accorded the unhappy distinction of being the first player permanently banished from major league baseball.30

With playing professional baseball no longer an option, Bechtel fell back on his off-season occupation of Philadelphia blacksmith. By the time of the 1880 US Census, he was married to the former Grace Horstful, a fellow Philadelphian some eight years his junior. But the union was a stormy one, with their marital problems exacerbated by Grace’s drinking. The couple soon separated, with George becoming a lodger at various Philadelphia addresses.31 One of Bechtel’s landladies, Sarah McGowan, eventually became George’s second wife in 1908.32 But this union, too, proved short-lived – Sarah passed away only months after the wedding.33

Throughout his 40-plus years in exile from the game, Bechtel lived in obscurity, his name rarely appearing in newsprint. For a time, he was reputedly employed making baseballs for the sporting goods company operated by old Philadelphia Athletics teammate Al Reach. During the 1890s, he also served a stint on the Philadelphia police force.34 For the most part, however, Bechtel stuck to blacksmithing. The last discovered press mention of his name placed Bechtel among the old-time ballplayers attending a banquet given for the World Series champion Philadelphia A’s in November 1910.35

On April 1, 1921, Bechtel suffered a stroke. Two days later, he died at St. Mary’s Hospital in Philadelphia.36 George W. Bechtel was 72. Following funeral services conducted at a local funeral parlor, the deceased was interred in Palmer Cemetery, Philadelphia. There were no immediate survivors of the man now considered, whether fairly or not, the first player permanently expelled from major league baseball.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Norman Macht and fact-checked by James Forr.

Sources

Sources for the biographical info imparted above include the George Bechtel file at the Giamatti Research Center, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Cooperstown, New York; the Bechtel profile in Major League Baseball Profiles, 1871-1900, Vol. 2 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2011); US Census data and other government records accessed via Ancestry.com; and certain of the newspaper articles cited in the endnotes. Stats have been taken from Baseball-Reference.

Notes

1 The younger Bechtel children were Ann (born 1854), twins Laura and Clara (1855), and Maria (1858).

2 Modern baseball reference works list Bechtel as bats and throws unknown, and no explicit mention of how Bechtel batted or threw was discovered in contemporary newsprint. But roughly 90% of the American population is right-handed, and the writer subscribes to 19th century baseball historian David Nemec’s dictum that right-handedness can be presumed in the absence of press mention that a player was left-handed, a noteworthy rarity in the 1870s.

3 Per the brief George Bechtel profile in “The Athletics of 1871,” New York Clipper, November 18, 1871.

4 Per Athletics game accounts published in the (Philadelphia) Evening Telegraph and Philadelphia Inquirer during the 1870 season.

5 “Base Ball,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 4, 1871: 2.

6 For Bechtel’s September 3 start against New York, a Pennsylvania newspaper reported that “the betting was 100 to 80 in favor of the Mutuals” at gametime. See “Base Ball,” Harrisburg Patriot, September 4, 1871: 1.

7 As reported in “General Notes,” (Philadelphia) Sunday Dispatch, December 31, 1871: 2. The Boston Red Stockings and Cleveland Forest Citys had also expressed interest in Bechtel.

8 See “Base Ball,” Brooklyn Union, February 26, 1872: 3. Only catcher Nat Hicks ($800) had a lower stipend.

9 For more, see William J. Ryczek, “The Mutual Base Ball Club” in Base Ball Founders: The Clubs, Players and Cities That Established the Game, Ryczek, Peter Morris, et al., eds. (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2013), 80-93.

10 See “The Louisvilles,” Chicago Tribune, April 16, 1876: 6.

11 “Base Ball,” Louisville Courier-Journal, May 31, 1876: 4.

12 Per “Louisville Gossip,” Chicago Tribune, July 9, 1876: 7.

13 “Louisville Gossip.”

14 As reported in “Bad Bechtel,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, June 16, 1876: 8; “The Bostons’ Record Against the Louisvilles,” Louisville Courier-Journal, June 15, 1876: 4; “Sporting Notes,” Boston Traveler, June 13, 1876: 1; and elsewhere.

15 “Louisville Gossip,” above, complete with verbatim re-prints of the June 2 and June 14, 1876 telegrams. Note: Bechtel’s Camden abode was located directly across the Delaware River from Philadelphia.

16 Daniel E. Ginsburg, The Fix Is In: A History of Gambling and Game Fixing Scandals (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 1995), 42, citing unidentified “New York papers.”

17 See e.g., “Two for the Right,” Chicago Tribune, February 4, 1877: 7: “Bechtel was dropped by the Louisville Club under circumstances so suspicious that he could not get a ‘clean bill.’”; “Bad Bechtel,” above: Bechtel terminated by Louisville for “crookedness.”

18 “George Bechtel and the Louisville Club,” Louisville Courier-Journal, June 20, 1876: 1.

19 “George Bechtel and the Louisville Club.”

20 “Louisville Gossip.” The letter was dated June 24, 1876 and signed “B.F. – Guilty Party.”

21 According to “Two for the Right.”

22 The Louisville club had attempted to rescind the expulsion of Bechtel and the Mutuals signed Bechtel apparently on the representation of Philadelphia Athletics manager Al Wright that Bechtel was eligible for National League play. See “Al Wright and Bechtel,” Chicago Tribune, February 18, 1877: 7.

23 See “Base Ball Jottings,” Philadelphia Times, June 29, 1877: 3. According to another source, Bechtel was “expelled from the [National] League under Sec.1 (now Sec. 2) of Art. V of the League Constitution” and that the Mutuals “were officially notified of Bechtel’s expulsion some time before the games were played.”; “Questions Answered,” Chicago Tribune, February 11, 1877: 7.

24 Per “Local Summary,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 27, 1877: 3; “Short Stops,” Indianapolis Sentinel, April 17, 1877: 5.

25 See again, “Base Ball Jottings.”

26 See “Some of the Most Sort,” Chicago Tribune, August 5, 1877: 7. The handwritten June 28, 1877 Bechtel reinstatement petition is reproduced in Jacob Pomrenke, “Gambling in the Deadball Era,” June 16, 2021, accessible via www.thenationalpastimemuseum.com.

27 “Some of the Most Sort.”

28 As reported in “The Case of George Bechtel,” Chicago Tribune, December 9, 1877: 7; “Base Ball,” Lowell (Massachusetts), Citizen, December 6, 1877: 2; “The National Game,” Philadelphia Times, December 5, 1877: 1; and elsewhere.

29 At the time, considerable debate focused upon Bechtel’s eligibility to play for one NL club (NY Mutuals) if he was on the “expelled” list of another club (Louisville Grays) and the consequences of ineligibility. See again, the February 1877 Chicago Tribune articles cited above.

30 See e.g., John Thorn, “Our Game: Baseball’s Bans and Blacklists,” February 8, 2016.

31 In 1890, Grace Bechtel’s alcoholism led to her institutionalization. See “Mrs. Bechtel’s Bad Habit,” Philadelphia Times, August 28, 1890: 1.

32 Per State of Pennsylvania marriage records accessed via Ancestry.com.

33 A death notice for Sarah Bechtel was published in the Philadelphia Inquirer, August 5, 1908: 7.

34 According to “Comment on Sport,” Philadelphia Inquirer, February 8, 1892: 3, which had Bechtel walking a quiet beat in West Philadelphia.

35 See “World’s Baseball Champion Heroes in Great Parade,” Philadelphia Inquirer, November 6, 1910: 13.

36 Per the George Bechtel death certificate, accessed via Ancestry. The Bechtel death notice published in the Philadelphia Inquirer, April 5, 1921: 7, invited “relatives, friends, and A.J. Reach & Co.” to funeral services.

Full Name

George A. Bechtel

Born

September 2, 1848 at Philadelphia, PA (USA)

Died

April 3, 1921 at Philadelphia, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.