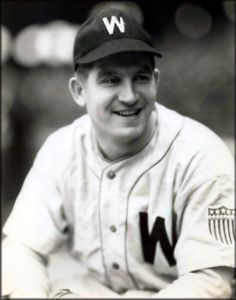

Bert Shepard

Baseball lore is filled with stories of players who distinguished themselves on the diamond despite physical limitations. Examples include Dummy Hoy, Three-Finger Brown, One-Armed Pete Gray, Monty Stratton, and more recently, pitcher Jim Abbott. But Washington Senators left-handed pitcher Bert Shepard remains the only player to have ever played in the major leagues on an artificial leg.1

Baseball lore is filled with stories of players who distinguished themselves on the diamond despite physical limitations. Examples include Dummy Hoy, Three-Finger Brown, One-Armed Pete Gray, Monty Stratton, and more recently, pitcher Jim Abbott. But Washington Senators left-handed pitcher Bert Shepard remains the only player to have ever played in the major leagues on an artificial leg.1

His big-league career lasted all of one game, a mop-up relief appearance against the Boston Red Sox on August 4, 1945. After wounds sustained in World War II necessitated the amputation of the lower part of his right leg, Shepard nonetheless achieved his life-long dream of pitching in the major leagues. Shepard’s lone big-league game was a small footnote to an otherwise remarkable life. Bert Shepard was one of the few ball players who could claim they were an inspiration to thousands of Americans and countless wounded war veterans.

Robert “Bert” Earl Shepard was born June 28, 1920, in Dana, Indiana, a small town north of Terre Haute near the state’s western border with Illinois, to John and Lura Shepard. Dana’s other famous resident was World War II war correspondent Ernie Pyle. Although his given first name was Robert, he went by “Bert” all of his life. Bert was the second of six sons born to the Shepards. He had an older brother Charles, and four younger brothers: Wayne, John, Gene, and Martin.

His father John, a native of Kansas, had a delivery business, but when the Great Depression hit, was forced to take jobs as a laborer, first on a fruit farm and a later on a county road crew. Around the time he was ten years old, Bert went to live with his maternal grandmother in nearby Clinton, Indiana. He remembered first being introduced to baseball by listening to the St. Louis Cardinals in the 1931 World Series on his grandmother’s radio.

He grew up hunting, fishing, and playing sports with his brothers. Years later his younger brother John recalled “… he was just naturally good at everything he did. He was a good swimmer, a good football player, and he played basketball well. He just made things look easy.”2

Clinton had no high school baseball team, so as a teen Shepard played briefly with a semipro team in his home town. After his junior year, he believed that he had the talent to make it as a professional baseball player. Shepard hopped a freight train and headed to California, where he found a job at a tire retread plant. He continued to play baseball on Sundays on the local sandlots, and word soon got out about the young lefty.

In 1939, Doug Minor, a scout for the Chicago White Sox offered Shepard a minor-league contract for $60 a month, and he was assigned to Jeanerette, Louisiana in the Evangeline League. In 1940, Shepard pitched for Wisconsin Rapids in the Class D Wisconsin State League, compiling a winning record, but experienced control problems, walking 48 batters in 43 innings.

The White Sox released him, and he returned to Clinton to finish high school, graduating in 1940. In 1941, Shepard rekindled his baseball dream and was signed by the St. Louis Cardinals organization, and was sent to Anaheim in the California League. Later that year he joined Bisbee in the Arizona-Texas League. In 1942, he pitched for La Crosse in the Wisconsin League. He continued to struggle with his control, walking 122 in 172 innings, which contributed toward a 9-13 record and a 4.45 ERA.

With the country now embroiled in World War II, Shepard enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Force at Fort Benjamin Harrison in Indiana on March 18, 1943. He was sent to Daniel Field, Georgia, where he attended flight school and earned his pilot’s wings and was commissioned as a 2nd Lieutenant. In early 1944, Shepard arrived at Wormingford, England, and joined the 55th Fighter Group, flying Lockheed P-38 Lightning fighters. In March, 1944 he was with the first Allied planes that ever flew over Berlin in the daytime.

On May 21, a massive assault on an airfield east of Hamburg, Germany was planned. Shepard was not scheduled to take part in this mission but, realizing the importance of it, he volunteered. This was Shepard’s 34th mission over Germany, and he believed he would return in time for a baseball game he had scheduled for later that afternoon. After destroying a train and an oil tank, he was headed for home when he encountered anti-aircraft fire. One of the shells tore through his right leg and foot, and another clipped Shepard’s chin, knocking him unconscious. His low-flying plane crashed into the ground at an estimated speed of 380 miles per hour.

Shepard was first found by German farmers who wanted to kill him with their pitchforks. Fortunately, Ladislaus Loidl, a Luftwaffe physician, and two armed soldiers arrived at the scene and held back the farmers at gunpoint. German doctors amputated Shepard’s leg 11 inches below the knee, and after recovery, he was transferred to a prison camp at Meiningen, in central Germany. Also at the camp was Dr. Errey, a Canadian medic, who fashioned an artificial leg. After becoming familiar with his crude prosthesis, Shepard began playing catch with a cricket ball and then resumed pitching a baseball.

After eight months as a P.O.W., in February 1945, Shepard was involved in a prisoner exchange and returned to Clinton, where he began practicing baseball with some players from a local semipro team. Realizing that he was still able to throw his familiar pitches, Shepard became determined to resume his professional baseball career. Shepard went to Walter Reed Hospital in Washington to be fitted with a new prosthesis, and he was visited by Robert Patterson, the Undersecretary of War, who presented him with a commendation for his service, valor, and courage. Patterson asked Shepard what his goal was, and the former flyer replied he wanted to play baseball.

When Patterson returned to his office, he called his good friend Clark Griffith, owner of the Washington Senators, and Griffith offered Shepard a tryout. On March 10, Shepard received his new leg, and four days later, he reported to the Senators training facility in College Park, Maryland. The Senators had no intention of using him in a regular game, figuring to keep him around to serve as coach and batting practice pitcher. Shepard said, “I think Mr. Griffith did it out of sympathy more than anything.”3

Shepard always contended that it was fortunate he lost his right leg instead of his left. As a left-hander, he used his left, good leg, for balance and to push off the pitching rubber, and landed on his right, the one with the prosthesis. When he received the opportunity to pitch, he proved he could throw hard and he moved around so well that it was difficult to tell he wore an artificial leg. Griffith was impressed, and on March 29, 1945 he signed Shepard to a major-league contract. He was promised that once he regained command and control of his pitches, he would be placed on the Washington roster as a pitcher.

Shepard hadn’t pitched in a game situation for many months and was still getting use to his new leg. The only problem he demonstrated was the need to work on his control. Griffith believed that would be solved through work in real game situations and scheduled Shepard to pitch in a couple of exhibition games. He pitched effectively against the Norfolk Naval Training Station and then on July 10, Senators’ manager Ossie Bluege named Shepard the starting pitcher when they played the Brooklyn Dodgers in an exhibition game for the War Relief effort.

Before the game, Shepard was met at home plate by General Omar Bradley, who pinned the Airman’s Medal on Shepard’s baseball uniform. Bluege had planned on using him for only the first three innings. Since Shepard only gave up one hit, Bluege let him pitch into the fourth inning before he was relieved. Impressed with Shepard’s performance, the Senators added him to the active roster after the game was over.

In addition to pitching batting practice for the Senators, he visited veteran’s hospitals, offering encouragement to other wounded veterans, and made a training film for amputees returning from the war. Shepard became something of a national post-war celebrity. “I got an awful lot of publicity right away. That sort of helped me to stay with the ballclub until I could prove myself. I pitched several exhibition games and got ‘em out each time,” Shepard said”4

Shepard remained in the Senators bullpen over the next few weeks until August 4, 1945. In a game against Boston, the Senators found themselves down 14-2 in the fourth inning, and the Red Sox had the bases loaded with two men out. Washington was playing their fourth consecutive doubleheader, and an already thin pitching staff was getting battered by Boston. With nothing to lose, Bluege brought Shepard in to try and stop the damage, and he struck out the first batter he faced. He stayed in the game and, for the remaining five innings, gave up only one run on three hits.

“I came in with the bases loaded, and I struck out George “Catfish” Metkovich to get us out of it,” Shepard told The International Herald Tribune in 1993. Though the score gave the Senators little chance of winning, “there was much more pressure on me than it seemed,” Shepard said. “If I would have failed,” he told the newspaper, “then the manager says, ‘I knew I shouldn’t have put him in with that leg.’ But the leg was not a problem, and I didn’t want anyone saying it was.”5

With this successful debut, it appeared Shepard was destined for a bright future in the major leagues. Unfortunately, it was the only regular season game in which he ever appeared. With the Senators battling the Detroit Tigers for the American League pennant in 1945, Bluege was reluctant to use Shepard. His only other on-field highlight occurred on August 31 when Shepard received the Distinguished Flying Cross between games of a doubleheader. The Senators released him on September 30.

Shepard reported to training camp with the Senators in the spring of 1946. But, with many former major-league players returning from the war, he was unable to make the opening day roster, and the Senators again signed him as a coach. During the 1946 season, Shepard became restless, wanting to get out on the field again as a player. He requested to be sent down to Chattanooga, in the Southern League, where he would be an active player. His request was granted, but because of the stretch of time in which he had been inactive, Shepard once again struggled with control.

Shepard struggled in 1946 because of soreness in the stump of his amputated leg. At the conclusion of the baseball season, he went back to Walter Reed Hospital and had more taken off the leg. Having been released by the Senators, Shepard signed a contract with the St. Louis Browns in April 1947. He had a tryout at the team’s spring training camp in Miami, but was sent to the Browns farm club in Elmira, New York in the Eastern League.

After being released by the Browns later that year, Shepard received an offer to play for the semiprofessional team in Williston, North Dakota. Williston had a reputation as being one of the top semipro teams in the nation. When the first Western Canada Baseball Tournament was held at Indian Head, Saskatchewan in early August, two teams from the U.S. were invited to compete; Williston and the Ligon Colored All-Stars out of Brawley, California. Shepard threw a three-hitter, but was defeated by Ligon, and their star pitcher Ladd White, 1-0. While in Williston, Shepard met his future wife Betty, a school teacher, and they were married in 1953.

Later that year, Shepard returned to Walter Reed for more surgery and, during 1948, was confined to crutches for much of the time. In 1949, Shepard was signed to pitch and manage the team at Waterbury, Connecticut in the Colonial League. He said that the reason he wanted to manage was because “Always before I’ve had a manager who was afraid to take a chance on me. Now, it’s up to me. Every fourth day when I make up the lineups, that ninth man is going to be B. Shepard, pitcher.”6

He was so confident in his ability to still be an effective pitcher that he suggested he be paid a salary of $1 for the season, with the stipulation he receive $400 for each pitching victory. He eventually agreed to a salary of between $4,000 and $4,500, but in August, when the club said they could no longer afford his salary, he was released as manager. His ballclub threatened to go on strike until a player’s committee raised enough money from local merchants to pay their manager for the rest of the season.

Shepard was out of baseball the next two years. In 1950 and 1951 he lived in Elizabeth, New Jersey and worked for International Business Machines (IBM) selling typewriters. Convinced he could still play, in 1952 Shepard played briefly for Hot Springs, Arkansas in the Cotton States League, and was also player-manager for St. Augustine in the Florida State League. He appeared in two games with Tampa in the Florida International League in 1953.

That season he also played briefly in Fergus Falls, Minnesota and began scouting for the Washington Senators as well.7 In 1954, he returned to North Dakota and was named player-manager of the Williston Oilers in the semipro Manitoba-Dakota League. The Oilers got off to a slow start and Shepard was let go. His final appearance in Organized Baseball was a handful of games with Modesto in the California League in 1955.

When he was unable to play baseball after recovering from his many surgeries, Shepard took up golf. He frequently participated in golf tournaments where his partner was a good friend, Yankee shortstop Phil Rizzuto. He never used a cart, always insisting on walking the golf course. He boasted, “I can play 36 holes of golf every day, and still be able to take my turn pitching.”8 In 1968 and 1971, Shepard won the U.S. amputee golf championship.

After retiring from baseball, Shepard and his wife moved to southern California and he became a safety engineer for Hughes Aircraft. He also worked in the same capacity for a construction company and several southern California insurance companies before retiring in 1982. In his later years, he served as an advocate for the rights of disabled workers. He designed an artificial ankle that allowed those with severe leg injuries like his, a great deal more mobility.

Shepard suffered a stroke and died on June 16, 2008, while a resident of a nursing home in Highland, California at the age of 87. He was survived by his former wife Betty (they had divorced a few years before his death after 48 years of marriage), two sons, Justin and Preston, two daughters, Penny and Karen, and nine grandchildren. He was also survived by three of his brothers; Martin, Gene, and John.9

Late in life, when Shepard was in his 70s, he said he often wondered, “Who carried me from the wreck?”, and “Who saved my life?” Little did he know that around the same time a British businessman, who knew of Shepard, went on a hunting trip to Hungary. There he met a fellow hunter, a retired doctor named Ladislaus Loidl, who told a story of how he had once rescued a wounded American flier from his downed plane. Loidl recalled that his wife had made a dress out of the airman’s parachute, and remembered reading the name Bert Shepard on the pilot’s dog tags.

The British hunter suggested Loidl contact Shepard. He did, and in May of 1993, the two men met at the doctor’s home in Austria, 49 years after their first meeting on a German battlefield. The reunion was featured in an episode of This Week in Baseball. “I prayed for this,” said Shepard. “And after half a century, my dream has incredibly come true.”10 Achieving this dream may have been even more important to Shepard than his earlier dream of playing major-league baseball.

Last revised: March 22, 2021 (ghw)

Sources

Anton, Todd. No Greater Love (Burlington, Massachusetts: Rounder Books, 2007).

Curt Eriksmoen, “One-legged baseball player defies the odds”, Bismarck (North Dakota) Tribune, September 22, 2013, and “Loss of leg didn’t stop baseball player,” September 29, 2013.

Bloomfield, Gary L. Duty, Honor, Victory: America’s Athletes in World War II (Guilford, Connecticut: Globe Pequot, 2002.)

Deveaux, Tom. The Washington Senators, 1901-1971 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2005).

Finoli, David. For the Good of the Country: World War II Baseball in the Major and Minor Leagues (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2002).

McGuire, Mark and Michael Sean Gormley, Moments in the Sun: Baseball’s Briefly Famous (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 1999).

Newell, Rob. From Playing Field to Battlefield: Great Athletes Who Served in World War II (Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 2006).

Swaine, Rick. Beating the Breaks: Major League Ballplayers who Overcame Disabilities (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2004).

Tellis, Richard. Once Around the Bases (Chicago: Triumph Books, 1998), 107-120.

Tim Wolter, POW Baseball in World War II: The National Pastime Behind Barbed Wire (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2002.

Notes

1 Stratton pitched in the minor leagues after being fitted for a prosthetic leg, but never returned to the majors.

2 Rob Newell, From Playing Field to Battlefield: Great Athletes Who Served in World War II, (Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 2006), 110-116.

3 Bert Shepard obituary, “WWII pilot lost leg, made the big leagues,” Los Angeles Times, June 20, 2008.

4 The Associated Press, “Bert Shepard, WWII vet and MLB player, dies at 87,” June 20, 2008.

5 New York Times, June 20, 2008.

6 Springfield (Massachusetts) Republican, March 15, 1949.

7 Williston (North Dakota) Herald, April 17, 1954.

8 Williston Herald, April 19, 1954.

9 Bert Shepard obituary, New York Times, June 20, 2008.

10 Michael Jaffe, “At long last, Thank You! Ex-major leaguer Bert Shepard finally met the enemy who saved his life in ’44,” Sports Illustrated, June 28, 1993.

Full Name

Bert Robert Shepard

Born

June 28, 1920 at Dana, IN (USA)

Died

June 16, 2008 at Highland, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.