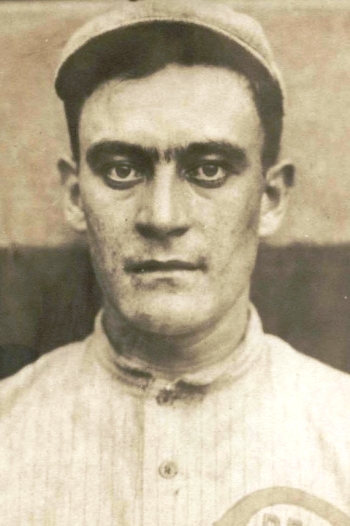

Clarence Mitchell

A major-league pitcher for 18 years, Clarence Mitchell is best remembered not for a pitch he threw from the mound, but for one he hit while standing in the batter’s box. It was Sunday, October 10, 1920, the fifth game of the World Series between Cleveland and Brooklyn. The series was tied at two games each, but in this game the Indians had knocked out Burleigh Grimes early and were leading 7-0 at the end of four innings. Pete Kilduff led off the top of the fifth for the Dodgers with a single to left field. Otto Miller followed with a single to center. So there were two men on base and nobody out when Clarence Mitchell, who had entered the game in relief of Grimes, stepped up to the plate. He hit a line shot up the middle, just to the second baseman’s right, a rising liner that looked like a sure base hit. But second baseman Bill Wambsganss was off with the crack of the bat, running toward second and making a tremendously high leap to spear the ball. One out. Wamby’s motion carried him toward second, and he tagged the bag to double up Kilduff who was still running toward third. Two out. Then Wamby noticed Miller, who had come down from first base, was standing a few feet away, so he tagged him for the third out. Shortstop Joe Sewell later said that he thought that Wambsganss was going to throw to first to double off Miller, but that he yelled, “Tag him!” Mitchell became the first—and, so far, only—man to hit into an unassisted triple play in a World Series. The next time up, Clarence hit into a double play, making him responsible for five outs in two consecutive trips to the plate, another World Series record.

A major-league pitcher for 18 years, Clarence Mitchell is best remembered not for a pitch he threw from the mound, but for one he hit while standing in the batter’s box. It was Sunday, October 10, 1920, the fifth game of the World Series between Cleveland and Brooklyn. The series was tied at two games each, but in this game the Indians had knocked out Burleigh Grimes early and were leading 7-0 at the end of four innings. Pete Kilduff led off the top of the fifth for the Dodgers with a single to left field. Otto Miller followed with a single to center. So there were two men on base and nobody out when Clarence Mitchell, who had entered the game in relief of Grimes, stepped up to the plate. He hit a line shot up the middle, just to the second baseman’s right, a rising liner that looked like a sure base hit. But second baseman Bill Wambsganss was off with the crack of the bat, running toward second and making a tremendously high leap to spear the ball. One out. Wamby’s motion carried him toward second, and he tagged the bag to double up Kilduff who was still running toward third. Two out. Then Wamby noticed Miller, who had come down from first base, was standing a few feet away, so he tagged him for the third out. Shortstop Joe Sewell later said that he thought that Wambsganss was going to throw to first to double off Miller, but that he yelled, “Tag him!” Mitchell became the first—and, so far, only—man to hit into an unassisted triple play in a World Series. The next time up, Clarence hit into a double play, making him responsible for five outs in two consecutive trips to the plate, another World Series record.

The only son of Catherine “Kittie” Buster and William Mitchell, Clarence Elmer Mitchell was born February 22, 1891, in a sod house on Turkey Creek, just north of Naponee in southwestern Franklin County, Nebraska, only a few miles from the Kansas border. The 1900 census showed nine-year-old Clarence living with his mother in the household of her parents, Mary and Samuel Buster, on a Franklin County farm near Bloomington. Raised on his father’s and grandfather’s farms, Clarence played sandlot baseball throughout his childhood, whenever he could take time from his farm work. By 1908, he was the star pitcher for Franklin High School. During the summer, he pitched for the town teams of both Franklin and Cowles, in adjoining Webster County.[1] His desire to become a professional baseball player may have been the reason he dropped out of high school to take a clerking job in Cowles in April 1909. This gave him time to play for any club needing his services, usually as a pitcher, but also as an outfielder or first baseman. He won five games and lost two for the Franklin club in the independent Nebraska State League that summer, but pitched mainly for a semipro team in Alliance in the far western part of the state. Andrea Paul wrote that he won 40 games and lost only four that summer.[2]

Clarence broke into professional baseball with Red Cloud of the Class D Nebraska State League in 1910. When the decennial census was taken that summer, he was listed as a baseball player living in Marion Township, Franklin County, in the household of his mother Kittie and his stepfather, Samuel H. Braden, a farmer. At the end of the season, he was signed by the Detroit Tigers and ordered to report to the Bengals’ spring training camp in Louisiana in 1911.

He divided the 1911 season between Saginaw of the Southern Michigan League and the big-league club, where he was used mainly as a batting-practice pitcher. Making his major-league debut with the Detroit Tigers on June 2, 1911, he appeared in five games, winning one and losing none that year. His win came on June 18 at Bennett Park in Detroit as the Tigers overcame a 12-run deficit to defeat the Chicago White Sox. (The Bengals had been behind 13-1 in the fifth inning.) The 20-year-old rookie entered the game in the eighth inning with his team trailing 15-8. He shut the Sox down in the top half of the inning. In the home half, he collected his first major-league hit as he singled off the third base bag, and eventually scored as did four of his teammates, making the score 15-13. Clarence retired the side in order in the top of the ninth. In the bottom of the ninth, the Tigers tallied three times to win the game 16-15. Clarence was credited with the win, and Hall of Fame pitcher Ed Walsh was charged with the loss. It was the first time in the twentieth century that a team had overcome a 12-run deficit to win a major-league game.[3] Mitchell was cut from the Detroit team before the 1912 season began.

Regarding Clarence’s dismissal from the Tigers, Andrea Paul repeated a widely told story that she said may have been apocryphal. “According to observers at the scene,” she wrote, “Mitchell was warming up while being watched by Detroit manager Hughie Jennings. After observing a few pitches that behaved oddly, Jennings asked. ‘Say, what the hell are you throwing?’

‘A spitball,’ says Clarence.

‘And with a left hand?’ roared Jennings. ‘There ain’t no such animal. Get out of here!’”[4]

Jennings was very nearly right. A left-handed spitballer is among the rarest of all animals. Clarence Mitchell was the only legal left-handed spitball pitcher to appear in a major-league game since 1920, and there were few, if any, before that. Mitchell doctored the baseball with slippery elm sliced from a special tree on the farm of a neighbor, Jess Williams, in Franklin County.[5] For a while, he collected his own supply. Later, when Clarence was a teammate of Burleigh Grimes on the Brooklyn Dodgers, Wallace Mitchell cut out pieces of wood from that same tree for his stepfather and Grimes to use.

On December 27, 1911, Clarence married a Franklin County girl, Lulu Wilson. The union was short lived and produced no progeny.

In 1912 and 1913, he played outfield and did some pitching for the Providence Grays of the International League. He hit .288 in 1912 and .333 in 1913, and earned a reputation as one of the best fielding outfielders in the International League. His won-lost record was 7-6 and 4-5 in the two years. Mitchell would have preferred to pitch, but his hitting and fielding were so good that his manager wanted him to be an everyday player.

In 1914, Mitchell played for the Denver Bears of the Western League, hoping to be used only as a pitcher. He won eight games and lost six. However, his hitting and fielding prompted manager Jack Coffey to insert him as the regular leftfielder. Paul quoted a Denver newspaper report that “If Mitchell was Christy Mathewson himself Denver couldn’t afford to take him out of left field now, because he is hitting at a .400 clip and covering worlds of ground in the garden.”[6]

The following year, Denver’s weak pitching staff needed bolstering, and Mitchell was used almost exclusively as a pitcher. He responded by winning 22 games, his only 20-win season in nearly 30 years in organized baseball. After the end of the season, Clarence joined Frank Bancroft’s National League All-Stars on a West Coast tour. He won three out of the four games in which he pitched. He also pitched one game for the American League team and won that one, too. Bancroft was the business manager of the Cincinnati Reds, and Mitchell’s performance led to his signing a major-league contract with the Reds in 1916.

The Reds tied for last place in the National League in 1916, so Mitchell’s 11-10 record was quite good under the circumstances. Paul wrote that the lack of run support cost Clarence eight losses—games the Reds lost by one run.[7] Had the Reds scored two more runs in each of those games, Mitchell’s record would have been a sensational 19-2. Unfortunately for the spitballer, it did not happen.

Despite a respectable 3.22 earned run average, lack of run support contributed to a 9-15 record in 1917. Mitchell was waived by the Reds and picked up by the Brooklyn Dodgers. Clarence had absolutely no luck at all in 1918. He started one game and retired only one batter, giving up four runs for an astronomical earned run average of 108.00. He also played a few games at first base and in the outfield with some success. In 10 games, he hit .250 and had a respectable slugging average of .375. However, he joined the Army and missed most of the season. While stationed at Camp Mills with the 342nd Field Artillery, he received a furlough and played in a game on June 13 against the Reds at Ebbets Field for the benefit of the Bat and Ball Fund Day. The two clubs agreed to give 25 per cent of the receipts to the fund, which was established by Clark Griffith to provide balls, bats, uniforms, and other baseball paraphernalia to armed services training camps. In addition, school children from Brooklyn were admitted to the grandstand behind third base for a nominal charge of ten cents. Nine cents of this went to the Ball and Bat Fund and the remaining one cent to the government as a war tax.[8] Unlike some ballplayers who stayed stateside during the entire war, Mitchell went to France with his unit, where he starred on the American Expeditionary Force baseball team. He played first base; fellow Nebraskan Grover Cleveland “Pete” Alexander was the team’s outstanding pitcher.

During the winter of 1918-19, the Dodgers considered converting Mitchell into a first baseman and playing him regularly at that position as a replacement for long-time star Jake Daubert, who had been released. Before Clarence got back from France, however, the Robins purchased Ed Konetchy from the Pirates, so Mitchell continued as a pitcher and pinch hitter. In 34 games, he hit .367 and compiled a slugging average of .449. On the mound he went 7-5.

As a pitcher in 1920, Clarence won five and lost two. He played a few games at first base and in the outfield. As a pinch hitter, he collected six safeties in 18 attempts. For the first time in his career, he made it to the World Series, where he made his place in history by hitting into that famous triple play, followed by a double play. However, he did make a hit in his other time at bat. On the hill in relief of Burleigh Grimes, he performed admirably, pitching four and two-thirds innings without giving up a run.

While with the Dodgers, Clarence married a Brooklyn woman, Marion Watson (nee Shaw), who was an office clerk for a publishing company. Marion had a son, Wallace, who was six years old in 1920. After the marriage, Wallace’s surname was changed to Mitchell, and Clarence raised him as his own.

In 1921 as the only left-handed spitball pitcher in the majors, Mitchell had an apparent advantage. Since only a few right-handed spitballers had been grandfathered, they had little opportunity to practice hitting the spitball. In addition, Mitchell had a three-way spitter. The usual spitball dropped when it reached the plate. Mitchell could make his break down, up or away, as he desired, so the batter could not anticipate its location even if he could discern that a spitter was on its way. He had his best major-league season yet, with 11 wins, nine losses, and an ERA of 2.89, which was excellent in that first year of the lively ball era, and he tied for the league lead in shutouts.

Clarence was looking forward to a good year in 1922, but the spitball artist got into only five games, losing all of his three decisions. Konetchy had retired, and manager Wilbert Robinson inserted Mitchell at first base. He performed well, fielding almost flawlessly and hitting .290. However, he hurt his right knee in a game in Boston in June. Although the injury was not believed to be serious and he stayed in the game, the leg grew steadily worse and finally Robbie had to sit him down.

On February 15, 1923, Brooklyn traded Mitchell to the Phillies for Columbia George Smith, a right-handed pitcher. The fact that Clarence was a holdout influenced the Brooklyn club’s decision to trade him, president Charles Ebbets admitted. “We reduced Mitchell’s figure because it was felt he would be useful in only a utility capacity.”[9] As usually happened when a grandfathered spitballer was traded, the team giving up the grandfather got the worst of the deal. In the remainder of his major-league career, Smith won three games and lost six. The 1923 Phillies were a last-place team, as they usually were in the 1920s. Hugh Fullerton sized them up correctly during spring training when he wrote, “It is a sad duty to chronicle the fact that I came to find a baseball team and failed to find anything but…a lot of second raters, has-beens, and never wases. . . .. Clarence Mitchell, who was used all round at Brooklyn, may prove a real help to the Phils. Brooklyn used Mitchell as first baseman, pinch hitter, pitcher and what not, and Fletcher (the Philadelphia manager) intends to keep him steadily on the pitching job. . . . It is a bad ball club which will have to have a world of luck to win fifty games and beat any one out.”[10] Fullerton hit it right on the nose. The Phillies won exactly 50 games and finished in last place. Mitchell won nine and lost ten for the cellar dwellers.

Mitchell endured several more losing seasons as he continued toiling for mediocre teams in Philadelphia. His record from 1923 through 1927 was 40 wins and 57 losses as the Phillies finished in eighth place three of his five years with them. By this time, Clarence had slowed down somewhat in his delivery. As he did not have a good fastball, he had to get by on his spitter and his smarts. If he threw 120 pitches in a game, as many as 75 or 80 of them would be spit balls. His former Brooklyn teammates nicknamed him “Old Bullet Ball” in good-natured recognition of the fact that his pitch did not resemble a speeding bullet. However, his hometown supporters believed he could still pitch. Paul quoted the Franklin County Sentinel of June 17, 1926: “Maybe there isn’t much on the ball except the cover and maybe the fellows do poke it here and there for many hits, but trying to get a run off this cunning old timer is like trying to take a bone from a cross dog.”[11]

The Phillies gave Mitchell his unconditional release on May 28, 1928. Losing one’s job may not seem like a lucky break, but for Clarence it was. He left the perennial tailenders, who were on their way to a 109-loss season. One week later, he was signed by the St. Louis Cardinals, who were on their way to the World Series. On June 6, his new team faced the New York Giants and fell behind 5-0 in the second inning as the Giants pounded Grover Alexander. From the third frame on, the McGrawmen scored only one more run, as the Cards turned around to win the game. “The main reason for this,” wrote Richards Vidmer, “was an old, worn out, cast-off, left-handed spitball pitcher by the name of Clarence Mitchell. Only recently the Phils cast him adrift. When the Phils cast a ball player adrift he generally drifts on and on. Not so Mr. Mitchell. In fact he scarcely had time enough to get used to his new freedom from the clutches of the Phils than he was grabbed and signed by the Cards. Jimmy Wilson, who used to catch Mr. Mitchell’s left-handed slants in Philadelphia, seemed to have the idea that a pitcher of Mitchell’s ability shouldn’t be allowed to wander around loose like that. Jimmy was so positive that he convinced President Sam Breadon and Manager McKechnie of the fact, and it looks as though Jimmy was right.”[12]

Clarence allowed the Giants only three hits in the remaining seven innings of that game and was the winning pitcher as the Cards moved ahead of the Giants into second place in the National League. He helped the Redbirds take over first place in the pennant chase and in one notable game on August 5 pitched into the 15th inning as they defeated young Carl Hubbell and pulled six and one-half games ahead of the second place Giants. After the Cardinals clinched the pennant, the Los Angeles Times ran a feature on five outstanding Redbird players who played a big part in winning the pennant for St. Louis. Among the quintet was Mitchell, of whom the feature writer stated “his signing by the Cardinals was a master stroke for Breadon. Mitchell has taken part in some twenty-nine games and they do say that he has deserved to lose only one of these games. The veteran has pitched marvelous ball against all the four other contenders….Mitchell should have as much credit as any man on the team. He is the only left-handed spitballer in captivity….He is smart, cool, and game.”[13]

Cardinal manager Bill McKechnie agreed: “I’d say he has done as much as any other ball player on the club to win the championship for us.”[14]

Although the New York Yankees had swept the Pittsburgh Pirates in the 1927 World Series, they were decided underdogs in the 1928 fall classic. The majority opinion held that superior pitching would bring the crown to St. Louis. How wrong this opinion was! The Cardinals never had a chance as the Yankees swept their second consecutive World Series. In game 2, Mitchell relieved Alexander with one out in the third inning, the bases loaded, and the Cards already trailing 6-3. The veteran spitballer hit a batter and allowed one base hit, permitting two runs to score. Mitchell allowed only one more hit and one run in the remainder of the game, but the contest was already lost. The Yankees won 9-3. A Washington Post writer opined that had Clarence started the game instead of Old Pete, the series might now be tied at one game apiece. He wrote that Mitchell deserved to start one of the games in the Mound City.[15] However, the Cardinal manager had other ideas, and St. Louis lost both games.

Mitchell won eight games for St. Louis in 1929 and started the 1930 season with them. After winning the only game he appeared in for the Cardinals, he was traded to the New York Giants on May 15 for right-handed pitcher Ralph Judd. True to the tradition that spitball grandfathers outperform those for whom they are traded, Clarence had one of his best major league seasons ever, winning 11 games while losing only three for a league leading .786 percentage in 1930. On the other hand, Judd never won a single game for the Cardinals or any other major-league team, and by the end of the season he was gone from the majors, never to return.

Mitchell’s 1930 performance was cause for celebration in Nebraska. When the veteran returned to Franklin, he was met at the train station by an enthusiastic reception, complete with a band concert and a ceremonial presentation of a new hunting outfit. Hunting was always Clarence’s main off-season avocation. He owned hunting dogs and enjoyed chasing after rabbits and coyotes. He became the official coyote catcher of Franklin County. During the 1936-37 off-season, he received seven dollars per pelt and averaged six kills per week.[16] He often hosted other baseball stars, such as Alexander, Grimes, Sunny Jim Bottomley, and Red Ruffing, on hunting trips in the nearby Nebraska and Kansas countryside. Frequently, he pitched for local semipro teams and sometimes enticed fellow major leaguers to appear in the games with him.[17]

Throughout his life, Mitchell considered Nebraska his home. Even when he was away playing baseball he was listed in the Franklin County censuses of 1910, 1920, and 1930, for that is where his family lived year round and where he always joined them during the off-season. The 1930 census listed his wife Marion, his son Clarence Jr., and his stepson Wallace. Clarence Jr., also became a professional baseball player, appearing with the Oklahoma City Indians of the Texas League and other teams.

In 1931, Mitchell won 13 games for the Giants. Surprisingly, that was the most victories he ever posted in any of his 18 major-league seasons. In a game at Philadelphia’s Baker Bowl on July 11, Clarence benefited from some extraordinary hitting by his teammates. The Giants amassed 28 hits and tied the modern major-league record of 58 at-bats in a nine-inning game.[18] Mitchell coasted to a 23-5 win, allowing four runs before turning the game over to the 20-year-old rookie, Hal Schumacher, in the ninth inning.

A New York sports columnist wrote, “Clarence is no Dazzy Vance for speed and curves and he hangs up few strikeouts, but he has a slow ball that has a tantalizing break when properly moistened and he gets results that keep him in the big show.”[19]

Before the 1932 season began, Mitchell celebrated his 41st birthday. He had been pitching since he was a child, and it was thought that his arm was starting to wear out. He was used sparingly that spring. On April 20, he won a major-league game for the last time, pitching a complete game and defeating the Philadelphia Phillies 14-5. The task was made easy for the ancient hurler by the heavy clouting of his teammates, especially Bill Terry, who for the second day in a row hit two home runs in a game. Clarence’s last start came against the St. Louis Cardinals on June 21. Mitchell pitched well in a losing effort, giving up only six hits in six innings, but three of the hits were bunched with the only free pass the pitcher allowed and an error to plate three runs for the Cardinals in the second inning. Meanwhile, the Cards’ young and eccentric right hander, Dizzy Dean, shut the Giants down until the last frame of the 5-1 game. In late June, manager Bill Terry removed Mitchell from the active roster, but retained him as a coach. On November 30, Clarence was given his unconditional release. In 18 seasons as a major-league pitcher, Mitchell had won 125 games, lost 139, and compiled a 4.12 earned run average.

But the veteran spitballer’s arm was not yet gone. Near the end of January 1934, the Mission Reds of the Pacific Coast League let it be known that if the league would let down the spitball bar for Mitchell, they would sign him. By a six to two vote, the PCL magnates approved his admission. Clarence joined Jack Quinn as one of the two spitball grandfathers to toss the moist delivery on the shores of the Pacific in 1934. Mitchell had far greater success than Quinn on the coast. Clarence won 19 games for the Reds in 1935 and six more the following season. In 1936, he won seven and lost four as a player-manager for Omaha in the Western League. Later, when he was manager of minor-league clubs in Mayfield, Kentucky, and Meridian, Mississippi, he made an occasional appearance on the mound. He pitched two innings for Meridian in 1940 at the age of 49. He pitched and/or managed semiprofessional teams in Broken Bow, Nebraska, and Marysville, Kansas, for a year or so. He helped establish the Cornhusker League, a semipro circuit that operated in Nebraska until 1953, and played with and managed the Aurora team in that league for several years.[20]

During the early years of World War II, Mitchell worked at the Cornhusker Ordnance Plant in Grand Island. In 1943, he and Marion moved to Aurora, where they operated a tavern. To commemorate his fall classic fiasco, Mitchell had a key chain made in the shape of a baseball bat. On one side was inscribed an advertisement for his tavern. On the reverse, these words appeared: “Beat this Record, Two times at Bat, Result Five Outs in Brooklyn-Cleveland World Series, 1920.”[21]

In 1953, Mitchell was named to the Nebraska Sports Hall of Fame. When baseball historian Jerry Clark chose his All-Nebraska All-Star team he selected four starting pitchers—Grover Cleveland Alexander, Bob Gibson, Mel Harder, and Clarence Mitchell.[22]

Mitchell suffered a circulatory ailment in the late 1950s. His right foot was amputated at Lutheran Hospital in Grand Island on December 29, 1958. Eventually both legs were amputated, and he was confined to a wheelchair for the last five years of his life.

On November 6, 1963, Clarence Mitchell died of a heart ailment about one hour after entering the Veterans Hospital in Grand Island, Nebraska. Funeral services were held November 9 in Aurora. He was survived by his widow Marion and two sons, Wallace and Clarence Jr.

Sources

This account is adapted from the chapter on Clarence Mitchell in Charles F. Faber and Richard B. Faber, Spitballers: The Last Legal Hurlers of the Wet One. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2006. Additional information was acquired through correspondence with Andrea Faling of the Nebraska State Historical Society.

[1] Andrea Paul, “The Life and Times of Clarence Mitchell,” NEBRASKAland, (Aug. 1993): 38.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Joseph J. Dittmar, The Baseball Records Registry: The Best and Worst Single-Day Performances and the Stories Behind Them. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 1997, pp. 82-85.

[4] Ibid. , p. 40

[5] Jerry E. Clark, Nebraska Diamonds: A Brief History of Baseball Major Leaguers from the Cornhusker State, Omaha: Making History, 1991, p. 17.

[6] Ibid., p. 41.

[7] Ibid., p. 41.

[8] New York Times, June 13, 1918.

[9] Washington Post, Feb. 16, 1923.

[10] Chicago Tribune, Mar. 31, 1923.

[11] Paul, op. cit., p. 44.

[12] New York Times, June 7, 1928.

[13] Los Angeles Times, Sep. 30, 1928.

[14] Paul, op. cit., p. 44.

[15] Washington Post, Oct. 10, 1928.

[16] Chicago Tribune, Mar. 3, 1937.

[17] Paul, op. cit., pp. 42, 44-45.

[18] Dittmar, op. cit., pp. 224-225.

[19] Ibid., p. 45.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Jerry Clark, op cit., p. 18.

[22] Ibid., p. 74.

Full Name

Clarence Elmer Mitchell

Born

February 22, 1891 at Franklin, NE (USA)

Died

November 6, 1963 at Grand Island, NE (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.