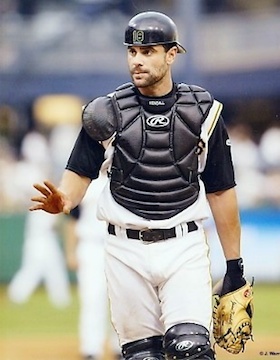

Jason Kendall

Mothers will do anything for their children. If you were Patty Kendall, those selfless duties would have included hitting ground balls to your son Jason, sometimes for hours on end, until he missed one. “That was the deal,” said Patty. “If he missed one, I went in. He used to keep me out there for two hours some nights.”1

Mothers will do anything for their children. If you were Patty Kendall, those selfless duties would have included hitting ground balls to your son Jason, sometimes for hours on end, until he missed one. “That was the deal,” said Patty. “If he missed one, I went in. He used to keep me out there for two hours some nights.”1

Patty knew her ballplayers, catchers in particular. She married one, Fred Kendall, who played 877 big league games over 12 seasons, mainly for the San Diego Padres. She gave birth to two more, first Mike, and then Jason Daniel, on June 26, 1974, in San Diego, California.2 Jason wasn’t born wearing the tools of ignorance, but he may as well have been. As his father’s baseball career was winding down in San Diego, a young Jason hobnobbed with the likes of future Hall-of-Famers Ozzie Smith and Dave Winfield, soaking up the atmosphere of a major league dugout. Possessing speed, toughness, and a fondness for contact, he played quarterback on the Torrance High School football team and catcher for the baseball team. His love of baseball even influenced his decision on what position to play. “(Jason) really loves the game,” said his coach at Torrance High School, Jeff Phillips. “In fact, he loves baseball so much that he told me that he wanted to play catcher just so he could handle the ball even more.”3

Kendall worked hard to improve his abilities while at Torrance, and it led to an outstanding junior year in which he hit .477 with a school-record 49 RBIs. He also threw out 64 per cent of baserunners trying to steal. Going into his senior year, Baseball America ranked him 15th among high school prospects in the country. He was no slouch on the football field either, passing for 2,962 yards and 23 touchdowns as a junior.

He considered joining Mike, a pitcher, on the San Diego State University baseball team and had even committed verbally to the school’s baseball coach, Jim Dietz. But the Pittsburgh Pirates had drafted him in the first round, 23rd overall, in the 1992 amateur draft, so he decided to turn professional. His progression through the minor leagues was steady, although he got off to a rough start in his first assignment with the Pirates’ Rookie Ball team in the Gulf Coast League. In 33 games he hit only .261 with no home runs and 10 RBIs. He had bigger problems defensively: 13 passed balls in 30 games, the most of any season in his career. (His highest total as a major leaguer was 12 in 2007, and it took him 132 games to reach that.)

Kendall joined the Class A Augusta Pirates for the 1993 season and showed clear improvement offensively, raising his batting average to .276 and hitting his first professional home run, but he still struggled defensively, committing a career-high 20 errors. He began showing some offensive pop in 1994 with the Salem Buccaneers in the Advanced Class A Carolina League, hitting .318 with seven home runs and 66 RBIs. He also played 13 games with the Class AA Carolina Mudcats of the Southern League at the end of 1994 and joined them for the 1995 season. He got the parent club executives salivating by batting .326 with eight home runs and 71 RBIs. He showed some improvement defensively, committing only eight errors, but he still had 11 passed balls. Nonetheless, he led the Mudcats to the Southern League championship, and the Pirates named him their minor league player of the year.

The rookie-laden Pirates were coming off a horrible season in 1995 where they had a 58-86 record, worst in the National League.4 Kendall arrived at the team’s spring training camp in 1996 believing that a good mental attitude would allow him to bypass AAA and come to “The Show” directly. “I’ve always thought that if you’re mentally aware, you can play anywhere,” he said. “If it’s Pittsburgh, I know mentally I’ll be focused. I know aspects of (being in the major leagues) are going to be different. [They are] the best players around. But I think I can handle it. That might sound cocky, but that’s how I feel.” That cockiness helped him land the starting catcher’s job, and on Opening Day, he proved to the Pirates that they made the right move, going 3-for-4 with a double and two RBIs as the Bucs defeated the Florida Marlins 4-0.5

One of his first career milestones had a family connection. He hit his first major league home run on May 8, 1996, off Bob Tewksbury of his dad’s former team, the Padres. (His dad, however, retained family bragging rights because he hit his first homer off HOF fire-baller Bob Gibson.) While power was rare for Kendall his rookie year—he hit only three home runs all season—he showed remarkable consistency at the plate the first two months of the season. He slumped in early June, going 6-for-31 in the first 10 games of the month, but some rest helped. “Jason is a little tired right now,” said Pirates manager Jim Leyland on June 15, 1996. “But he’s a tough kid. “There are athletes and there are baseball players. Jason Kendall is a baseball player, although he happens to be a pretty good athlete.”6

Leyland wasn’t the only National League manager impressed with Kendall. Atlanta Braves manager Bobby Cox chose him as a reserve for the National League All-Star team, a rare honor for a rookie, particularly a catcher. He came in as a defensive replacement in the ninth inning but didn’t get to bat in the National League’s 6-0 win.

Kendall didn’t let up in the second half and continued hitting steadily, winding up with a .300 average on the nose with three home runs and 42 RBIs and a .372 on-base percentage. His defensive struggles continued, though. He led the league in errors by a catcher with 18. He also threw out only 23 per cent of runners attempting to steal. Nonetheless, major league managers made him the only unanimous selection for the Topps’ Bubble Gum Card All-Rookie team that included Derek Jeter. (Jeter missed being a unanimous selection by one vote.) He also placed third in NL Rookie of the Year voting behind Todd Hollandsworth of the Los Angeles Dodgers and Edgar Renteria of the Florida Marlins.

Kendall set off a media stir in spring training 1997 when he called out some of his young teammates for the way they conducted themselves. Even at age 23 he was taking on a leadership role by expecting his mates to stop thinking so highly of themselves and get down to work.

“We’ve got some guys walking around—without naming names—hats on backwards, like, ‘Yo, yo, yo, cool as can be,’” he said. “C’mon man. You played in Lynchburg last year. You were 10-10. Who cares? Shut up. Get your job done.”7

For Kendall, part of getting the job done was improving on his throwing, the main cause of his defensive woes during his rookie season. He had a hitch in his throw that delayed getting the ball to second base. The extra work paid off as he committed only 11 errors in 1997 despite handling 180 more chances than the previous year; he also threw out 37 per cent of runners. Those numbers prompted Pirates management to rip up his contract and give him a four-year extension.

Kendall was baseball’s version of Rodney Dangerfield in 1998—he “didn’t get no respect” when it came to All Star Game votes from the fans. By the end of June he was hitting .335, with a .413 OBP, five home runs, 38 RBIs, and nine stolen bases. But he finished a faraway fifth in the balloting for the midseason classic, miles behind Mike Piazza’s nearly 3 million votes. Nonetheless, NL manager Jim Leyland, who happened to be Kendall’s first manager in Pittsburgh, selected him as a reserve player. Again he appeared only briefly, getting a two-out single off Troy Percival in the ninth inning while pinch-hitting for Javy Lopez. The hit only delayed the inevitable, however, as the American League won the game 13-8.

Regardless of what the fans thought, Kendall had no trouble proving what a tough cuss he was, leading the NL in getting hit by a pitch, with 31. He had the same number in 1997 but finished a league second that season to Craig Biggio. Getting hit by pitches became somewhat of a Kendall specialty. He became the first batter in the 20th century to be hit by a pitch 30 times in a season twice. As good as he was it at, Kendall made clear that it was not a skill he worked on. “It’s not like I go home and practise it in the off-season,” he said. “I don’t stand in the batting cage and point to my shoulder and say, ‘Try over here.’”8

Kendall didn’t shirk physical contact of any kind. On June 28 he got into a fight with Gary Sheffield of the Dodgers when the two collided in a play at the plate in which Sheffield was called out. Sheffield knocked Kendall’s helmet off as he got up, whereupon Kendall jumped Sheffield and the fun ensued as the benches cleared. Both players were suspended for three games. Kendall appealed his suspension and lost. None of those plunks or punches prevented him from having another fine season, however. He finished the year hitting .327, good for fifth in the National League, with 12 home runs, 75 RBIs, and 26 stolen bases, a NL record for catchers (since 1900).

Although he didn’t party like it was 1999 when that season began, Kendall did reach rarefied heights for a catcher, namely, the leadoff position in the batting order.9 The idea hatched when the Pirates’ leadoff hitter from 1998, Tony Womack, was traded to the Arizona Diamondbacks. The experiment with Kendall lasted until the end of April; on May 1 he was back in the fifth spot in the batting order. Kendall’s unusual season came to an abrupt and frightening end on July 4 at Three Rivers Stadium against the Milwaukee Brewers. While trying to beat out a bunt for a base hit in the bottom of the fifth, he stepped awkwardly on the first base bag, dislocating his right ankle so severely that the fibula bone protruded from his skin. He also tore three outside ankle ligaments and one inside ligament. He had surgery, and, according to team orthopedist Jack Failla, required at least three months of rest and rehabilitation. Kendall being Kendall, he was telling teammates he might be back in September, although that wasn’t going to happen. “I think Jason Kendall thinks he’s going to play again this year, but, realistically, he’s not,” said Pirates manager Gene Lamont. “When he gets back he’ll realize how tough it is.”10

Kendall was in the middle of an excellent season when the injury occurred; he was hitting .332 with eight home runs and 41 RBIs and 22 stolen bases in 78 games. He was also showing great improvement in his ability to throw out base stealers, gunning down 43 per cent of potential thieves, compared to a 28 per cent success rate in 1998. In a sad irony, he finished second to the Mets’ Mike Piazza in fan voting for the All-Star Game he couldn’t play in. Piazza had 1,645,304, while Kendall had 511,587.

A gruelling off-season rehabilitation schedule followed Kendall’s recovery from surgery. He spent eight hours a day, six days during the off-season, working with a trainer and a physical therapist. Kendall showed no sign of the injury when he arrived the following February at spring training in Bradenton, Florida. “Kendall did not favour the ankle or limp even slightly as he shagged fly balls, warmed up pitchers and knocked several balls over the left-field fence on the first day of the Pittsburgh Pirates’ camp,” wrote Alan Robinson of the Associated Press.11

After an uneventful spring, which for Kendall was good news, Buc manager Gene Lamont decided that his catcher was number one in his books. Kendall began the season batting leadoff, and while he got off to a slow start—only seven hits in his first eight games—his timing came back and by the end of April, he was hitting .322 with an .831 OPS. The leadoff experiment only lasted 18 games, and after a stint in the number 3 slot, he hit second for most of the season. All of Kendall’s hard work after his injury paid off handsomely in 2000. On May 19 he became the first Pirate to hit for the cycle at Three Rivers, in a 13-1 romp over the St. Louis Cardinals. He also drove in five runs. On July 4, one year to the day after his injury, he hit a go-ahead two-run homer in the top of the ninth inning as part of a seven-run rally in a 10-4 Pittsburgh victory over the Cubs. He also finished second to Piazza in fan voting for the All-Star Game (2,780,452 votes to 745,614). But Kendall ended up starting in the Classic when Piazza pulled out due to a concussion, playing four innings and going 0-for-2 in a 6-3 AL win. Offensively, Kendall picked up right where he had left off in 1999. He batted .320 with a .412 OBP and an .882 OPS. He hit 14 home runs, drove in 58, scored 112, and stole 22 bases. His defensive statistics were a mixed bag. He led the league in putouts (990) and assists (81), but he was also tops in passed balls (11) and third in errors committed (10).

Kendall picked a good year to have fine offensive numbers. Premier catching talent was scarce, and the Pirates knew it. That’s why they tore up his existing contract, which would have paid him $3.1 million in 2001, and inked him to a six-year deal worth $60 million after the campaign. Taking a page from PR 101, Kendall claimed he stayed with Pittsburgh because of the chance to win, not because of the money. “If I didn’t believe we weren’t [sic] going to win here, I wouldn’t stay here, no matter how much money they gave me,” he said. “It’s going to happen here. I’ve just got that feeling.”12 But feelings can be deceiving; the team didn’t win. The Pirates had losing record in each of Kendall’s first five seasons. They lost 93 games in 2000 and would lose 100 games in 2001. In fact, they never played .500 ball in any of Kendall’s nine seasons with the team. Nor, ironically, was Kendall ever again selected to an All-Star game.

His team’s struggles and his own poor hitting in 2001 caused Kendall to explode on July 24 when he was ejected from a game against the Cubs for arguing a call and bumping with first base umpire Jim Wolf. His outburst earned him a two-game suspension (later reduced to one game.) “I just had a lot of stuff bottled up from the first 3½ months of the season and I lost my cool, which I shouldn’t have done,” he said. Kendall had reason to be frustrated. He was suffering career lows in several offensive categories, including batting average (.266), OBP (.335), and OPS (.693) He also had 10 home runs and 53 RBIs. The fall-off in production may have been aggravated by a thumb injury he incurred on Opening Day that required surgery after the season ended, although Kendall didn’t use it as an excuse. 13

His hitting woes continued early in the 2002 season, as he got off to a horrible start. By the end of April, he was hitting only .227 with zero home runs and five RBIs, four of which came in one game. Gradually, though, his numbers improved, and by season’s end he was up to .283. His production numbers, on the other hand, plummeted, the worst of his career. He hit only three home runs, five fewer than the 1999 season when he played only 78 games due to injury. He also drove in only 44 runs, just three more than in 1999. He went under the knife for the third year in a row when the season ended, this time to have a cyst and bone chips removed from his left foot.

The off-season surgeries and disappointing numbers Kendall posted since signing his huge contract had some wondering whether he was a bust. He even began hearing boos at home in 2002. By spring training 2003, however, Kendall was feeling better physically than he had since his ankle injury. He got off to an excellent start, hitting home runs in his first two games of the season (he didn’t hit his first home run of 2002 until May 7) and tied his home run production for all of 2002 in his first 25 at-bats. His average hovered around the .290 mark through early June, then he proved he was all the way back by getting ejected for his part in a fight with Marlon Anderson of the Tampa Bay Devil Rays. Kendall was suspended for three games; he appealed the suspension and lost. On July 3, his average passed the .300 mark, and it stayed there the rest of the season. He finished the year with a .325 average, six home runs, 58 RBIs, a .399 OBP, and an .815 OPS.

Kendall’s 2004 season was marked by a testament to his durability. He caught his 1,155th career game, breaking the franchise’s 88-year-old record held by George Gibson. Oh, and he got into another fight. This time he charged the mound after being hit by a pitch from Joe Kennedy of the Colorado Rockies on August 15. It was the 172nd time in his career that a pitcher plunked him, but the first time he ever charged the mound. Apparently Kennedy had sworn at Kendall and had told him to get out of the way of the pitch. Kennedy said that he was yelling at the umpire. Kendall went through what apparently was becoming an annual event, getting suspended for three games, appealing the suspension and losing the appeal.

A fighting spirit and franchise records did not compensate for the fact that Kendall’s salary ate up a significant portion of Pittsburgh’s modest payroll, so on November 27, 2004, the Pirates traded him to the Oakland A’s for pitchers Mark Redman and Arthur Rhodes. Kendall waived the no-trade clause in his contract to enable the deal, for two reasons. For Kendall it meant being back in California and, more importantly, with a winning team.

The impact of Kendall’s arrival in 2005 was felt particularly by middle relief pitcher Justin Duchscherer, because Kendall ruined Duchscherer’s plan to spend the All-Star break in San Diego with his family, but in a good way. Duchscherer was 3-1 with a 1.48 ERA and four saves when AL manager Terry Francona picked him to represent the A’s at the All-Star Game in Detroit. Duchscherer credited Kendall’s confidence in his pitches for his successful season.14 But Kendall himself had a mediocre season, batting .271 with no home runs and 53 RBIs. Nonetheless, for the first time he got a sniff of what a playoff race was like, although Oakland finished seven games out of the wild card spot with an 88-74 record. Kendall had never been that close to the playoffs before.

After a one-year absence, Kendall resumed his annual pas de duke-it-out in 2006, this time with John Lackey of the Angels on May 2. Lackey didn’t like Kendall leaning over the plate with his elbow and told him so in a tone that rubbed Kendall the wrong way. Kendall charged the mound and off they went. Kendall was suspended for four games and fined $2,000. He was going to appeal the suspension, but dropped it. The enforced rest may have done Kendall some good. He was batting .244 when he started serving his suspension but started hitting better upon his return. He finished the year with a .295 average, with one home run, 50 RBIs and a .367 OBP. More importantly, he got his first taste of post-season play, as the A’s won the AL West with a 93-69 record. They defeated the Minnesota Twins in the ALDS, but lost the ALCS to the Detroit Tigers.

All the years of catching began taking their toll on the 33-year-old in 2007, and by mid-season Kendall was hitting .226, with two home runs and 22 RBIs. On July 16, Oakland traded him to the Chicago Cubs for pitcher Jerry Blevins and catcher Rob Bowen. He batted .270 for the Cubs with one home run and 19 RBIs in 57 games. He also played in one game of the NLDS as the Arizona Diamondbacks swept the Cubs in three straight games.

The last three years of Kendall’s career were more notable for what happened off the field than on it. He spent 2008 and 2009 with the Milwaukee Brewers, reaching the post-season in 2008 for the third straight year with his third different team. The Brewers lost the NLDS in four games to the eventual world champion Philadelphia Phillies. He was rested fairly regularly in 2009, playing in 134 games. He also only almost got into a fight on July 20 against his former team, the Pirates. He was behind the plate when Milwaukee pitcher Chris Smith hit Pirates reliever Jeff Karstens with a pitch. Kendall restrained Karstens from going after Smith, then the benches emptied. Kendall got into a shouting match with Pirates’ pitching coach Joe Kerrigan, but nothing further happened and he was not suspended. Kendall hit .246 in 2008 and .241 in 2009. He hit a combined four home runs for the two campaigns with a total of 92 RBIs. After the 2009 season, Kendall signed with the Kansas City Royals.

Kendall hit .256 with the Royals in 2010, with no home runs and 37 RBIs. A free agent again after the season, he underwent shoulder surgery in September and again in July 2011, and was forced to miss the entire 2011 season. He signed a minor league contract with the Royals prior to the 2012 season, but retired after playing two games for the Northwest Arkansas Naturals of the Class-AA Texas League.

He ended a fine career in which he got more than 2,000 hits and became the only catcher in major league history with three straight seasons of 20 or more stolen bases. He decided that he wanted to stay with the Royals and predicted—accurately, albeit a little prematurely, as it turned out—as he did with the Pirates, that Kansas City was going to be a winner. “I live in Kansas and I want to stay in Kansas,” he said. “This team’s going to win, and I want to be part of it.”15

After retiring, Kendall served in various coaching capacities with the Royals at both the major and minor league levels and as a special assignment coach. In 2014, he wrote a book with Kansas City Star reporter Lee Judge called Throwback: A Big-League Catcher Tells How the Game Is Really Played. In it he reveals a lot about what is happening on the field, such as how catchers and umpires talk to each other during a game and how rain delays affect base running. In 2015, he watched his prediction about the Royals come true when they won the 2015 World Series.

Last revised: January 5, 2016

Sources

In addition to the sources listed in the notes, the author also used:

Chicago Tribune.

http://espn.go.com/

http://oakland.athletics.mlb.com/

http://www.nbcsports.com/

http://www.philly.com/

Index-Journal (Greenwood, South Carolina).

Indiana Gazette (Indiana, Pennsylvania).

Kansas City Star

News Record (North Hills, Pennsylvania).

San Francisco Chronicle.

Santa Cruz Sentinel.

Standard-Speaker (Hazleton, Pennsylvania).

Ukiah Daily Journal (Ukiah, California).

USA Today

Notes

1 Gerry Callahan, “Leading Man Batting First and Swiping Bases, Deceptively Laid-back Pirates Catcher Jason Kendall is Redefining His Position,” Sports Illustrated, May 3, 1999.

2 Mike Kendall never played major league baseball, but as of 2015, he is a highly successful scout with the San Francisco Giants.

3 Cap Carey, “Like Father, Like Son: Tradition Catches On . . . ” Los Angeles Times, March 6, 1992.

4 Teams did not play the customary 162-game schedule in 1995 because the season started late due to the continuation of the players’ strike that curtailed the 1994 campaign.

5 “Pirates Catcher Hopes to Skip Class AAA Enroute to Pittsburgh,” Gettysburg Times, February 20, 1996.

6 Kevin Roberts, “Big Game Gets Kendall a Day Off,” News Record (Hazleton, Pennsylvania), June 16, 1996.

7 “Kendall Blasts Teammates,” San Bernadino County Sun, February 24, 1997.

8 Keith Olbermann, “The Hits That Keep On Hurting Pirates catcher Jason Kendall doesn’t mind taking them for the team,” Sports Illustrated, June 15, 1998. Kendall stands fifth of the list of lifetime leaders in HBP, but he is far and away the leader in HBP for catchers, 254 to Carlton Fisk’s 143.

9 Before 1999, Jeff Newman and Butch Wynegar were the only catchers since 1970 to lead off more than 30 times in a season.

10 “Kendall’s return in 1999 unlikely,” Kokomo Tribune, July 6, 1999.

11 Alan Robinson, “Kendall: No pain, no problems on first day back,” Daily Herald (Tyrone, Pennsylvania), February 19, 2000.

12 Ibid., “Kendall: Pirates ready to start winning,” November 18, 2000.

13 Paul Meyer, “Pirates Report, 7/26/2001,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, July 26, 2001.

14 Duchscherer did not pitch in the game, which the American League won 7-5.

15 Dick Kaegel, “Kendall retires after ending comeback attempt,” mlb.com, July 24, 2012.

Full Name

Jason Daniel Kendall

Born

June 26, 1974 at San Diego, CA (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.