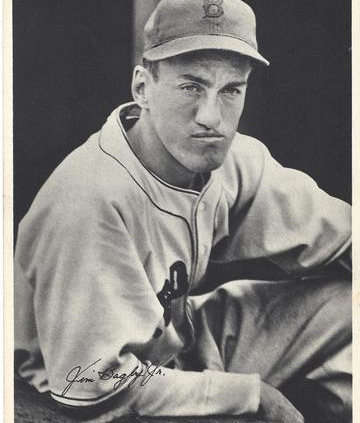

Jim Bagby Jr.

Jim Bagby Jr. was a second-generation major leaguer, his career neatly echoing that of his father, James “Sarge” Bagby, Sr. Both were right-handed pitchers; both at various times led the American League in innings pitched; and both spent the bulk of their careers with Cleveland. Both compiled some memorable seasons. Twice Jim’s pitching merited his selection to the All-Star game. When Jim Bagby, Jr. toed the rubber for the Red Sox in the 1946 World Series, the Bagbys became the first father and son to pitch in a World Series. However, Jim’s greatest fame came in 1941 when he ended Joe DiMaggio’s consecutive game hitting streak at 56.

Jim Bagby Jr. was a second-generation major leaguer, his career neatly echoing that of his father, James “Sarge” Bagby, Sr. Both were right-handed pitchers; both at various times led the American League in innings pitched; and both spent the bulk of their careers with Cleveland. Both compiled some memorable seasons. Twice Jim’s pitching merited his selection to the All-Star game. When Jim Bagby, Jr. toed the rubber for the Red Sox in the 1946 World Series, the Bagbys became the first father and son to pitch in a World Series. However, Jim’s greatest fame came in 1941 when he ended Joe DiMaggio’s consecutive game hitting streak at 56.

James Charles Jacob Bagby Jr. was born in Cleveland, Ohio, on September 8, 1916, while his father was pitching with the Indians. Jim spent much of his childhood in Atlanta, Georgia, where his father had settled after playing with the Atlanta Crackers of the Southern Association. Eventually the family re-located to the prosperous Atlanta suburb of Marietta, where both father and son resided until their deaths. The family was small but close. There were three children, Jim and his older sisters, Betty and Mabel, who was named after her mother, the former Mabel Smith. The bond between father and son was especially close.

As a child, Jim Jr. avidly followed his father’s career and spent a lot of time at Ponce de Leon Park, home field for the Crackers, starting when his father played there. When not watching his father play, Jim spent many hours playing catch with his dad. It wasn’t long before the younger Bagby learned all of his father’s pitches. Jim’s mother disapproved. Her thoughts, echoing those of so many baseball wives of the generation, were highlighted in a Liberty magazine profile that quoted her talking to her husband:

The conversation was repeated many times. Often enough to impress Jim Bagby Jr., young as he was. “I don’t know why you want him to grow up to be a baseball player,” his mother would say. “What has baseball ever done for you, Jim? You worked hard in the minor leagues for years, and then you were in the majors for a spell, and here you are in the minors again. After all those years what do you have to show for it? First I want our boy to have a good education, and then a job in some reliable business.”

The talk would die down, and then, when his mother had left the room, his father would ask, “Ready, Jim?” And Jim would nod eagerly and the two would go out behind the little house in Atlanta and play ball.1

Young Bagby’s course to the majors was not a straight line from childhood to adulthood. There came a time in his adolescence when he came close to giving up on baseball completely. As a 12-year-old he was the best pitcher on the Atlanta area sandlots but then mysteriously, Liberty recounts, his arm “went lame.” His mother’s emotions were mixed but young Jim felt that she was secretly glad of the situation.

For three years Jim didn’t touch a baseball. Things changed when he turned 15. Starting slowly, he ultimately rediscovered his old form. The team he played on tied for the city of Atlanta championship game but lost the playoff. The re-emergence of his son’s talent elated his father. The elder Bagby knew the owner of a semipro team in Montgomery, Georgia. Beginning in 1932, the son pitched semipro ball in Montgomery and was winning consistently.

In the spring of 1935 the senior Bagby finagled a tryout for his son with Cincinnati. Amid the hubbub of Chuck Dressen’s first full season as manager of the Reds, the gangly 18-year-old attracted almost no attention. Embittered, he left the Reds spring training camp on his own volition after three disheartening weeks. A pep talk from his father soon revived his spirits. When the Boston Red Sox played in Atlanta as they barnstormed their way north to open the season, the father tried something else.

Gaining the ear of Red Sox manager Joe Cronin, he arranged another tryout for Jim. Cronin liked what he saw and wired Eddie Collins to find a position for the 6-foot-2, 175-pound pitcher with great stuff and a solid assortment of pitches. As a result Jim found himself in the ranks of professional baseball as a member of Boston’s Piedmont League farm club, the Charlotte Hornets.

With the Class B Hornets he compiled a 13-9 record while appearing in 40 games and pitching 218 innings. Showing a maturity beyond his years on the mound, Bagby possessed a wicked curve, a fantastic changeup taught to him by his father, a sinker, and his main weapon, blinding speed. In 1936, Charlotte dropped out of the Piedmont League and the Red Sox switched their affiliation to the new team in Rocky Mount. Bagby was assigned there.

But Rocky Mount was a bit of a setback; Bagby compiled a 9-12 record while pitching 169 innings in 38 games with an ERA of 5.11. Despite the mediocre season, Jim was promoted to the 1937 Single-A Hazelton (Pennsylvania) Red Sox (New York-Pennsylvania League), where his talents emerged. He went 21-8 in 37 games (his 21 victories led the league) with a stellar ERA of 2.71 to earn not just league MVP honors but also a promotion to the majors.

Jim made his debut in a way that every kid in America dreams about. He started on Opening Day, April 18, 1938, against the world champion New York Yankees, the most potent lineup in baseball. When he arrived at Fenway, Jim had no idea he would be on the mound to kick off the season. In what was also the first major-league game he had ever seen, Jim found himself inserted as the starter by Joe Cronin. Cronin made the conscious decision to not tell Bagby sooner because he did not want the 21-year-old to mentally “pitch himself out” with distraction.2 Bagby pitched six innings and earned the win. The game was tied, 4-4, when he was lifted for a pinch-hitter and the Sox rallied to take an 8-4 lead. The lead held up and Jim Bagby, Jr. had the first of his 97 major-league victories.

Jim compiled a 15-11 record in 43 games, 25 as a starter. He had 10 complete games but achieved only one shutout that season, a tight 2-0 home win over the visiting Philadelphia Athletics on August 18. His ERA stood at 4.21 with 73 strikeouts – but 90 walks. He surrendered 218 hits and 110 runs. It was a fairly decent start for what became a successful career.

Once he made the majors, Jim and his father only argued about one issue: who was the better hitter. Both were good hitting pitchers, and Jr. actually was used as an occasional pinch hitter. His lifetime average of .226 was eight points higher than his father’s. The two were profiled in The Sporting News, the article ended thus: “But Junior is certain of one thing: that he can outhit the old man. The old man will grant him only one thing—that he probably gets more distance. ‘But look what he’s got to hit?’ says Pop, ‘Who couldn’t knock the rabbit ball a country mile?’”3

For Jim another life adventure began in the off season. On October 13, 1938, he married 21-year-old Leola Hicks in the pastor’s office of the Druid Hills Baptist Church in Atlanta. The two had met two years previously at a local basketball game. In a small, simple ceremony, Jim’s sister, Mabel – herself married for only a short time — served as the matron of honor. The marriage would last the rest of his life.

Perhaps he had played over his head in 1938, perhaps he was distracted by the responsibilities of being a new husband, but whatever the reason, Bagby came out flat in the 1939 season. He amassed a 5-5 record with an ERA of 7.09. In mid-season the Red Sox decided that he needed to be sent down to the minors to get his game back, so he was sent to the Little Rock Travelers of the Southern Association. The Southern Association was Class A1, just a notch above his most recent minor-league assignment, in Hazelton.

The demotion had exactly the effect the parent club desired. Bagby pitched to a 7-6 record and a 3.54 ERA with Little Rock. Whatever the Red Sox were looking for in him, Jim found it. He was back in the majors to stay in 1940, although at first it didn’t look that way. His 1940 numbers were nothing to get excited about: a 10-16 record in 36 games. His ERA of 4.73 was a tad high, although he began to work relief on a regular basis. The combination was good enough to keep Bagby in a Sox uniform.

On August 24, he found himself involved in perhaps the oddest moment of Ted Williams’ long career in Boston. Although Ted was to say, “The only thing dumber than a pitcher is two pitchers”. Ted had been pestering Joe Cronin to let him pitch. Ted liked to brag about his youthful pitching exploits and when the first game of a doubleheader against the Tigers turned into a 11-1 blowout, Cronin decided that it was time for Ted to put up or shut up.

Jim Bagby, who was on the mound, was moved to left field and Ted came in to pitch the final two innings. Ted faced nine batters, allowing three hits and one run. The highlight was striking out Rudy York on three pitches. Interestingly, the catcher was Joe Glenn, who had also caught Babe Ruth’s last major league pitching performance.

Jim stayed in a Red Sox uniform until December. The one thing the Sox lacked in 1940 was a quality catcher; at the league winter meetings, Joe Cronin, at the behest of Eddie Collins, rectified that problem. In a complicated deal to get Frankie Pytlak from Cleveland, Cronin “sold pitchers Fritz Ostermueller and Denny Galehouse to the St. Louis Browns for $30,000. Purchased Pete Fox from Detroit for an unannounced sum. Swapped Roger “Doc”Cramer, his veteran outfielder, to Washington for Gerald “Gee” Walker, and immediately turned over Walker, pitcher Jim Bagby and catcher Gene Desautels to Cleveland, receiving in return Pytlak, pitcher Joe Dobson, and infielder Odell Hale.”4

The deal was initially unpopular in Cleveland, as Pytlak was a fan favorite and the Indians seemed to get the worst of the deal. Bagby was perceived in Cleveland as a mediocre pitcher at best. It turned out that the Lake Erie air would eventually turn out to be just the tonic Jim needed.

The deal was, however, considered shrewd by most of the experts. The Sporting News ranked the Indians’ rotation of Bob Feller, Al Smith, Al Milnar, Bagby, and Mel Harder as “best in [the] loop.”5 Bagby’s season was not spectacular by any standard, but he did find a home with Cleveland. With the Tribe, Jim started 27 games but finished only 12; he won nine games while losing 15. His ERA was a pedestrian 4.04, but was an improvement over 1940. Interestingly, the same man who signed his father’s checks when he was with the Indians signed Jim’s as well. Indians bookkeeper Mark Wanstall had been with the club for 25 years. The Sporting News observed, “It happens only once in a lifetime, and can certainly occur only once in the history of major league ball in Cleveland.”6

Cleveland also offered some important off-field impact on his life. No doubt aware of his mother’s fears of a baseball career being an economic dead end, Jim enrolled in art school. Jim took morning classes at a Cleveland school; his long term goal was that of becoming a professional artist.

The highlight of his 1941 season would ensure that his name would live forever, if only as the answer to a trivia question. It is almost impossible to convey the atmosphere and the national mania that was singularly focused on July 17, 1941. For the previous 56 games, Joe DiMaggio had hit safely at least once. The streak was the centerpiece of the nation’s newscasts; it was followed breathlessly by newspapers and fans to the exclusion of all else. Attendance for Yankees games both at home and on the road soared. Some 67,000 fans turned out at Cleveland’s Municipal Stadium that night to see if “Joltin’ Joe” could extend the streak.

Cleveland starter Al Smith pitched the first 7 1/3 innings. He walked Joe once, and also got some exceptional help from third baseman Ken Keltner, who made two stellar grabs to retire DiMaggio in the first and seventh innings. Bagby came in with one out in the eighth inning. For years afterwards he would tell all who asked what he pitched that night. Most reporters over the years usually asked about that night in 1941 when the country watched him end DiMaggio’s streak. Jim loved to tell and retell the story. “Just fastballs”, Bagby said when asked about pitch selection by interviewer John Holway. Bagby continued, “Joe hit one of them hard but he just hit it at somebody.”7 DiMaggio hit into a 6-4-3 double play, Boudreau to Mack to Grimes, which just beat Joe to the bag. Ultimately the Yankees won the game, 4-3, but that was distinctly an anticlimax for the evening.

Jim achieved some professional highlights in 1942 and 1943. In both years he led the American League in games started. In 1942 he compiled a 17-9 record in 38 games. The 1942 season was Jim’s single greatest season. He started 35 games and recorded 16 complete games with 4 shutouts, both professional bests. His outstanding ERA of 2.96 was also his personal best. Jim was a natural selection for that July’s All-Star Game. In 1943 he returned to the All-Star Game but in neither year did he see action. His 1943 numbers were 17-14 in 36 games while leading the league in innings pitched with 273. His ERA of 3.10 however, was closer to his final major league average of 3.96. (His father led the American League twice in games, and once each in victories, complete games, and innings pitched.)

In 1944 Jim appeared in just 13 games before leaving baseball for a one-year stint in the Merchant Marine. His hitch was uneventful and perhaps left Jim with a desire for more. Early in 1945 Jim took the Army physical but was rated 4-F because of his harelip. He returned to the Indians for the final year of World War II and had an 8-11 record. He started 19 games and worked 6 in relief. On December 12, 1945, the fifth anniversary of the trade from Boston, he was traded back to Boston for pitcher Vic Johnson and cash.8

With Boston he was used almost equally as a starter and as a reliever. Bagby built a 7-6 record, he started 11 games and completed six with one shutout. He also relieved in 10 games. The highlight of his career came in October when the Red Sox went to the World Series against the St. Louis Cardinals. In Game Four, after Tex Hughson surrendered three runs in the second inning and two more in the third inning without recording an out, Bagby was called upon to face Enos Slaughter with Stan Musial stationed at second base. Bagby got Slaughter to ground out and Whitey Kurowski to foul out before Joe Garagiola singled to drive in Musial. Bagby struck out Harry Walker to end the uprising. In three full innings of work, Jim gave up one earned run on six hits and a walk. Jim flied out to center field in his one Series at-bat, falling short of his father’s 1920 feat: a pitcher hitting a home run in a World Series. Jim, Sr. was the first pitcher to homer in the fall classic.

On February 10, 1947 the Pirates bought Bagby from the Red Sox for slightly over the $10,000 waiver price.9 It turned out to be his last big-league season. In another parallel with his father, the Pirates were the last major-league team for both Bagbys. With the Buccos, his record was 5-4 in 37 games with an ERA of 4.67. He started six games and finished two of them, as he was used almost exclusively in relief.

His big-league career was almost the same length as that of his father. “Sarge” played nine years, while his son hung on for one more year, making an even decade in the bigs. The 1948 season found Jim in the Triple A American Association with the Indianapolis Indians, trying to pitch his way back onto the Pirates’ lineup. He amassed an impressive 16-9 record in 31 games but it wasn’t enough to get him back to the smoky Steel City. At the end of the season, the Pirates gave Jim his outright release.

As a free agent in 1949, Jim latched on with the Atlanta Crackers. He was pitching in his hometown, in the same stadium he had grown up in as he watched his father’s professional baseball life begin to sputter down. In 30 games he completed a 10-14 record in 178 innings, not quite good enough at age 33 for someone to pick up his option.

The story was even more interesting in his final year as a professional baseball player. With the Class B Tampa Smokers of the Florida International League he put on an impressive show with a 9-1 record in 26 games and 114 innings pitched. Not bad at all for a 34-year-old. His final big-league career record was 97-96 with an ERA of 3.96. He recorded 84 complete games and 13 shutouts. With the conclusion of that season, Jim adjusted to life without baseball. He settled in Marietta and began working as a draftsman in the aircraft industry. Those old art school classes he had taken in Cleveland paid dividends. This job lasted until he retired in the 1980s. He also began playing golf seriously. He had started golfing as a player but now had time to work on his game. He became adept enough at golf to turn professional, playing in tournaments on weekends or while on vacation from the airplane factory. These jobs paid him more than baseball had. A life-long smoker, Jim’s cancerous larynx was removed in 1982. From that point on he relied upon Leola to communicate with the world, as she became an accomplished lip-reader.

Jim’s cancer re-emerged in 1988 and killed him on September 2, just days before his 72nd birthday. Completing the pattern set in childhood, he was buried not far from his father in Atlanta’s Westview Cemetery. Jim followed his father posthumously in still another way in 1992. Ten years after his father had been enshrined, James Bagby, Jr. joined him in the Georgia Sports Hall of Fame.

Notes

1. Graham, Frank, “Bagby and Son.” Liberty, September 26, 1942 p.21

2. Clifford Bloodgood “Beginner’s Luck” Baseball, April 1941 p.487

3. Troy, Jack “Bagby, Jr, Just Like His Pop, Even to Ability to Sock, Happy with tribe for Whom Father had 31 wins in’20” The Sporting News February 27, 1941 p. 3

4. “Bosox Chief Lack Plugged by Pytlak In Three-Way Deal” The Sporting News December 19, 1940 p.1

5. McAuley, Ed, “Cleveland Pitching Keeps Its Date with Best In Loop Rating” The Sporting News April 24, 1941 p.1

6. “Once in a Lifetime” The Sporting News February 20, 1941 p.8

7. Holway, John B. “A Mystery Man in the End to DiMaggio’s Streak” The New York Times July 15, 1990 p. S1

8. Who’s Who in Baseball 1947, p.60

9. Doyle, Charles J. “Hank Quit When Bucs Snubbed His Bid For Release” The Sporting News, February 19, 1947 p.3

Sources

Graham, Frank “Bagby and Son” Liberty, September 26, 1942, p.21

Bloodgood, Clifford “Beginners Luck”, Baseball, April 1941, p. 487

Troy, Jack “Bagby, Jr. Just Like His Pop, even in the ability to Sock, Happy with Tribe for Whom Father had 31 wins in ’20” The Sporting News, February 27, 1941, p.3

“Bosox Chief Lack Plugged by Pytlak in Three Way Deal” The Sporting News, December 19, 1941, p.1

“Cleveland Pitching Keeps its Date with Best in Loop Rating” The Sporting News, April 24, 1941, p.1

“Once in a Lifetime” The Sporting News, February 20, 1941, p.8

Holway, John B. “A Mystery Man in the End to DiMaggio’s Streak” The New York Times, July 15, 1990 p. S1

Who’s Who in Baseball 1947, p. 60

“Hank Quit When Bucs Snubbed His Bid for Release” The Sporting News, February 19, 1947, p. 3

Statistics come from: Palmer, Pete and Gillette, Gary, The Baseball Encyclopedia (New York: Barnes & Noble, 2004)

Additional data from www.retrosheet.org and the Georgia Sports Hall of Fame and Museum website: http://www.gshf.org/site/

Full Name

James Charles Jacob Bagby

Born

September 8, 1916 at Cleveland, OH (USA)

Died

September 2, 1988 at Marietta, GA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.