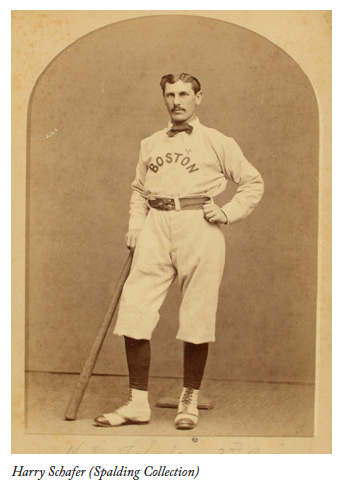

Henry C. Schafer

Henry Schafer was the first major-league player to spend a career spanning eight or more seasons entirely with the same franchise. He was called Harry, probably from early childhood, but had two more colorful baseball-related nicknames. One was Silk Stockings, but he was known best to fellow players as Dexter, the name of the most famous racehorse in North America in the late 1850s and the 1860s.1 Both nicknames remain without explanation; Schafer was neither particularly fast on the bases nor the scion of a notable family. Too, he was relatively colorless in all and is probably the least remembered regular on the Boston club’s dynasty in the 1870s.

Henry Schafer was the first major-league player to spend a career spanning eight or more seasons entirely with the same franchise. He was called Harry, probably from early childhood, but had two more colorful baseball-related nicknames. One was Silk Stockings, but he was known best to fellow players as Dexter, the name of the most famous racehorse in North America in the late 1850s and the 1860s.1 Both nicknames remain without explanation; Schafer was neither particularly fast on the bases nor the scion of a notable family. Too, he was relatively colorless in all and is probably the least remembered regular on the Boston club’s dynasty in the 1870s.

Born in Philadelphia on August 14, 1846, the 5-foot-9½, 143-pound right-handed hitter and thrower developed his game on Philadelphia’s Parade Grounds along with Bill Hague and Tom Miller. The son of teamster George Schafer, he was one of five children, among them three sisters (Mary, Eliza, and Ann) and a brother, John. His mother’s name appears to be missing from the 1850 census, suggesting that she may have been deceased by then, perhaps a victim of childbirth complications.2

Schafer began playing organized ball in 1867 with the local Arctic club and then joined the esteemed Philadelphia Athletics the following year, remaining with them through the 1870 season. His last game with the Athletics came on October 19, 1870, at Philadelphia when he played right field in place of West Fisler, who normally occupied the spot, and went 3-for-3 in a 15-3 win over the Brooklyn Atlantics. 3

When the National Association was formed in the winter of 1870-71, the Athletics were among the first teams to enlist in the first all-professional league, but had no use for Schafer, whose best position was third base. They had already signed Levi Meyerle, one of the strongest hitters in the game at the time, to man third base. Schafer, in contrast, was considered only a mediocre hitter but a respectable fielder and a very accurate thrower, though reportedly a trifle slow at getting rid of the ball.

Left unattached for the coming 1871 season, Schafer eventually signed with the Boston National Association entry, managed by the venerable Harry Wright, the chieftain of the fabled undefeated 1869 Cincinnati Red Stockings. He was in time to join the club in its inaugural spring training tune-up, a 41-10 drubbing in Boston of a local picked nine on April 6, “Fast Day,” in which he played third base.4 In his first official National Association game as a member of Wright’s cast on May 5, 1871, at Washington, Schafer again served at third base and bagged two hits in a loosely played 20-18 victory over the Olympic club’s Asa Brainard, who had been Wright’s pitching ace two years earlier on the Cincinnati Red Stockings.

Schafer ultimately participated in all of Boston’s 31 league games and finished with a .282 batting average, 28 points below the club’s final composite mark. At that, it was arguably his best season at the plate. In addition to his being the first to serve an eight-year career with the same team, Schafer was also the first position player to log as many as eight full seasons in the majors without ever batting .300. His peak year actually came in his rookie season when he achieved a .692 OPS thanks to a .296 on-base percentage and a .396 slugging average, both career highs. As might be expected, Schafer, after batting in the seventh slot in his initial major-league appearance, from then on generally batted last or next to last in the order.

After achieving regular status at third base in each of his five NA seasons with Boston, Schafer played every inning of every game at the hot corner in 1876 after the club moved to the fledgling National League once the NA disbanded; it was the ultimate tribute to his durability and the third and final time he had either led or tied for the league lead in games played. The first professional league’s dissolution was attributable in part to Boston’s dominance – four successive pennants after finishing second in 1871, and most by a gigantic margin.

When the Red Stockings returned to their winning ways in 1877 and copped the first of two successive National League pennants, Schafer suddenly found himself demoted to scrub status, playing in only about half of the team’s official games while versatile John Morrill saw the most duty at Schafer’s former sinecure, third base. Most of Schafer’s appearances were in the outfield, where his strong arm came in handy, but he showed little range and fielded an execrable .621, making 11 errors in the 29 chances that came his way.

When all of Boston’s regulars – including pitcher Tommy Bond – played almost every inning of every game in 1878, Schafer frequently appeared in exhibition affairs, playing a wide variety of positions, but saw action in only two official contests, both in the outfield, even though he was on the team all season.

His big-league finale in an official National League contest came on August 31, 1878, at Chicago, when he played right field and went 0-for-4 in a 5-2 win over Chicago’s rookie star, Terry Larkin. Exactly a month later, on September 30, in Boston’s last championship game of the year, Schafer, if he was in the park at all that day, was on the bench at Providence in a 2-1 loss to the Grays’ vaunted rookie John M. Ward. Assuming his presence at the game, since his contract was still in force until the season ended, it was his final day of active status as a big leaguer. Though the Bostons launched their annual fall exhibition tour of the East on October 2, just two days after the close of the official season, Schafer seems no longer to have been with the club. There is no evidence of him in any of Boston’s 1878 postseason box scores.

Since Schafer was so seldom employed in his last two seasons with Boston, there is good reason to speculate that he may have been kept on the team solely because he was among the several players Harry Wright signed to multiyear contracts after raiders from other National Association teams signed four of Wright’s biggest stars to contracts for the 1876 season while the 1875 campaign was still under way, and Schafer’s contract was a three-year deal that expired in the fall of 1878.5 In any event, Wright clearly made no effort to retain Schafer once the 1878 season was in the books. Seeing no more future for himself in the National League, Schafer joined several other former Boston players, including Andy Leonard and Tim Murnane, on the Albany club of the National Association (by then a minor league) in the spring of 1879, and later that season he played briefly with the Rochester Hop Bitters of the same loop. Toward the end of the summer the Cleveland Plain Dealer reported that he was “now manager of a Boston club room.”6

As late as 1886, Schafer considered making a comeback with the Rochester International Association team under manager Frank Bancroft, but wisely refrained in view of his age; he was by then nearing 40.7

Three years later, Schafer was listed among the many ex-Boston players the Chicago Tribune cited for being owed back pay from 1877 when Boston’s tight-fisted owner, Arthur Soden, taxed the entire Boston team 50 cents a day for expenses while on the road and $30 per year for uniforms, and held the assessed amount out of their last pay checks. Although the players agreed to it at the time because Soden cried poor and claimed club was losing money, they later learned differently.8 Not surprisingly, nothing came of the Chicago paper’s plea for belated retribution.

Over the next 30 years Schafer frequently appeared at old timer’s events in Boston and was a close follower of both Hub major-league teams, the National League Braves and the American League Red Sox. On one such occasion, when he was spotted in attendance at a local game, Sporting Life observed: “The veteran Harry Schafer, of the Bostons of the early days, scarcely ever misses a game and a better preserved and more genial chap one would scarcely want to meet. …”9

At some point during his playing days, Schafer married Delphine Knower, who predeceased him. The couple had one child, a daughter, Bertha. In May 1921, on the anniversary of Boston’s first major-league game 50 years earlier, he was among the four players from the team still alive, joining Cal McVey, Frank Barrows, and George Wright.10 Schafer was residing by then in Philadelphia with his daughter, having moved there from Boston several years earlier. He died in the city of his birth on February 28, 1935, at age 88 of chronic myocarditis, leading to mesenteric thrombosis, and was buried in Philadelphia’s Fernwood Cemetery.11

Notes

1 The Sporting News, January 4, 1896.

2 Ancestry.com.

3 New York Clipper, October 20, 1879.

4 New York Clipper, April 7, 1871.

5 Among them was Joe Borden who was stripped by Wright of his pitching duties during the course of the 1876 season and fulfilled the remaining time on his multiyear contract as a groundskeeper for the club.

6 Cleveland Plain Dealer, November 29, 1879: 1.

7 The Sporting News, June 21, 1886.

8 Chicago Tribune, February 3, 1889.

9 Sporting Life, June 29, 1907.

10 Boston Globe, April 17, 1921.

11 The Sporting News, March 7, 1935.

Full Name

Harry C. Schafer

Born

August 14, 1846 at Philadelphia, PA (USA)

Died

February 28, 1935 at Philadelphia, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.