Monty Stratton

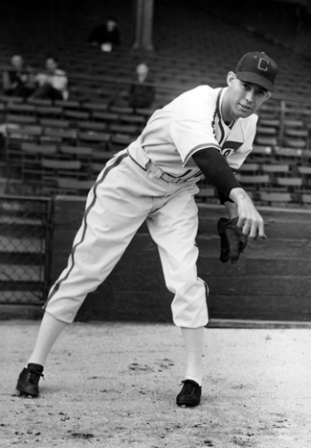

In the late 1930s, Monty Stratton of the Chicago White Sox was one of the best and most praised pitchers in major-league baseball and was about to enter the prime of his career. “Monty Stratton looks as if he is going to furnish many a page in baseball history before he gives up,” Philadelphia sportswriter James Isaminger wrote about the affable 6-foot-6 pitcher.1 “He is the nearest thing to Grover Cleveland Alexander,” said Cubs manager Charlie Grimm. “The same control, the same ‘dip’ on every pitch, the same smooth, confident motion.”2 But then came a dark November day in 1938 that would change the course of Stratton’s life.

In the late 1930s, Monty Stratton of the Chicago White Sox was one of the best and most praised pitchers in major-league baseball and was about to enter the prime of his career. “Monty Stratton looks as if he is going to furnish many a page in baseball history before he gives up,” Philadelphia sportswriter James Isaminger wrote about the affable 6-foot-6 pitcher.1 “He is the nearest thing to Grover Cleveland Alexander,” said Cubs manager Charlie Grimm. “The same control, the same ‘dip’ on every pitch, the same smooth, confident motion.”2 But then came a dark November day in 1938 that would change the course of Stratton’s life.

Monty Franklin Stratton was born on May 21, 1912, on his family’s farm in Wagner, Texas. He was the sixth of nine children born to Lee Davis and Minnie Aster Corine Stratton. While growing up on the farm, Stratton was too occupied with school and working the family farm to dream about becoming a major leaguer, although he did find some time to occasionally play ball with the other kids. “I played wherever they wanted me to,” he once said, which was usually first base or one of the outfield positions, but never pitcher.3 In 1930 Monty’s father, Lee Davis Stratton, died, leaving his widow the proprietor of the farm, thus forcing Monty to spend more time working the farm with less time for school and baseball. His heavy workload included attending to the livestock and working the cotton fields.

Stratton’s journey through life changed on a spring day in 1931, when a group representing the Wagner High School student body paid a visit to the Stratton farm before an important game against a rival high school. The Wagner team was in dire need of a pitcher for the big game, and the students were confident that Shorty,4 as the tall, lanky Stratton was called during his school days, was the one who could do the job. “I can’t pitch,” Stratton told them. “Never have pitched. You all is just plain screwy if you think I can pitch.”5

“Even if you can’t pitch, maybe you can scare ’em with your size,” one of the students said. “And you can throw a baseball mighty fast.”6

And so Shorty grabbed his mitt and tagged along with his classmates to the local field – and hurled a 2-0 shutout. His impressive performance created an opportunity for him to pitch for local semipro teams for as much as $2 a game.

In 1934, Stratton was pitching for manager Bill Webb’s Galveston Buccaneers of the Texas League, a team boasting a working agreement with the White Sox. “He had grand control from the beginning,” Webb would later say about his reason for signing Stratton.7 At Galveston, Stratton pitched well enough to convince Webb that he was ready for the big leagues. The White Sox sent the husband-and-wife scouting team of Roy and Bessie Largent to check him out. One practice session was all it took for the two scouts to agree with Webb, and the White Sox paid $1,200 for Stratton.8

After joining the White Sox in late May, Stratton was tutored by manager Jimmy Dykes and coach Muddy Ruel on how to study batters. Ruel also taught him how include a mix of overhand pitches to go along with his side-arm stuff and how to throw a sinker. Chicago second baseman Jackie Hayes tagged the rookie pitcher with the nickname Gander, which would stick with him throughout his major-league career.9

On June 2, with the White Sox trailing the Tigers 10-0 in the sixth inning, Dykes believed the time was right for Stratton to pitch in his first major-league game. The scribes in the press box immediately commented on his height. “Monty Stratton, who appears eight feet tall, but is only six feet six, pitched the last three innings and held the enemy to two runs, principally because his mates executed a couple of sterling double plays,” wrote the Chicago Tribune’s Edward Burns.10 One week later, feeling more seasoning was necessary, the White Sox sent Stratton to Omaha of the Western League.

At Omaha, Stratton became an immediate hit with the fans, for his size and his pitching; the local press referred to him as “that long lean fellow from the South with the amazing curve ball.”11Handicapped by a lack of hitting and fielding support, he still managed to win eight of his 18 decisions and struck out 11 or more batters three times. Also while in Omaha, he met a local resident named Ethel Milberger, an “attractive brunette.”12 The two began a courtship that would lead to marriage in January of 1936.

In 1935 Stratton reported to the White Sox spring training camp with his heart set on pitching the entire season in Chicago. A leg injury, however, limited his playing time, and before the season began he was assigned to the St. Paul Saints of the American Association. “The boy is fast, but he’s more than that,” said Saints catcher Tony Giuliani after a warm-up session with the new pitcher. “He has a sinker which is really deceptive. And his control is very surprising.”13 Stratton won his first four games, and by mid-July he was 14-5, which earned him a spot on the league’s All-Star team, where he continued to impress. “Stratton was far and away the outstanding performer on the field. He held the opposition hitless for three innings he worked, blazing his fastball by hitters and fooling them on his accurately breaking curve,” wrote Gordon Gilmore of the St. Paul Press.14

On August 29 the White Sox recalled Stratton, and a week later he pitched well in his first starting assignment, against the New York Yankees. “However, he had the misfortune to draw Charley Ruffing as an opponent. His season debut was impressive despite the score [Yankees 5, White Sox 4],”opined Edward Burns.15

Two weeks later Stratton faced another challenge when he was selected to start against the Cleveland Indians, who were riding an eight-game winning streak. “Stratton got off to an inauspicious start by allowing two first inning runs, but then held the Indians scoreless the rest of the way in a 9-2 Chicago win for his first major league win,” said the Chicago Tribune.16 He registered one more decision before the end of the season, a loss to the pennant-bound Tigers, to finish his 1935 major-league season at 1-2.

Tabbed a “prize rookie”17 and predicted to “cast terror through the American League this season”18 by sportswriter Irving Vaughn, Stratton was inserted into the White Sox starting rotation in 1936. In his first start of the season he beat the St. Louis Browns. He lost five of his next six starts, but according to Burns he was standing up well under the circumstances, and those setbacks were mostly due to “poor fielding techniques of (shortstop) Lou ‘Butterfingers’ Appling and lack of hitting support.”19

On May 25 it was reported that Stratton was suffering from sore throat, while a further examination revealed a case of tonsillitis. Before a decision could be made about surgery, his appendix began to ache and would have to definitely be removed. As he recovered from surgery, another operation was performed to remove his tonsils. The two operations made Stratton inactive until late August. He did return to action and pitched three more wins to finish the season at 5-7.

Stratton’s 1937 season began with a 5-1 win over the Browns. “Stratton operated in such talented fashion that most of the afternoon wore away before the enemy located second base,” wrote Vaughn.20 One week later he became the first American League pitcher of the season to record a shutout. By the time the All-Star break arrived, Stratton had 10 wins to earn a spot on the American League’s All-Star roster. However, a wrist injury sustained while sliding into second base at St. Louis on July Fourth canceled his trip to the midsummer classic in Washington.

Stratton’s injured wrist didn’t cause him to miss any starts, and on July 31 he blanked the A’s for his fifth shutout of the season. On August 5 he was pitching at Yankee Stadium in search of his 15th win when, in the bottom of the fifth, with Chicago ahead, 3-1, as Stratton threw to Yankees third baseman Red Rolfe, he felt a sharp pain in his throwing arm, forcing him to leave the game. Feeling he could work out the soreness, he continued to throw in the bullpen during the days that followed, but when that proved ineffective he submitted to an examination, which disclosed a tear in his right bicep.

When he felt well enough to pitch, he returned to the rotation on August 29 against the Philadelphia Athletics, and was knocked out of the box by an avalanche of hits before the first inning was over. He took more time to heal and returned to pitch the final game of the season, during which he was said to “look fair” but not sensational in gaining his 15th win.21 He finished his season with a 15-5 record, a 2.40 ERA and walked just 37 in 164⅔ innings pitched.

Before heading home to Texas for the winter, Stratton said he expected to win 20 to 25 games in 1938. On November 28 his wife gave birth to the couple’s first child, a boy, Monty Jr.

Could Monty Stratton repeat his 1937 performance of 15 victories? He looked good in his first two spring-training outings. In his next game, against the Chicago Cubs, he burned a strike past Billy Herman, then turned to the dugout to call for manager Jimmy Dykes. He felt a sharp pain his arm and asked to be taken out.

After spending the night with his arm packed in ice, and reading reports in the newspapers the next morning that his career might be over, Stratton paid a visit to Dr. Charles Spencer, a bone and muscle expert who specialized in treating athletes. The doctor’s diagnosis was that Stratton had sustained two tears in his right biceps, but predicted that he would be throwing again in 10 to 14 days. A few weeks later Stratton said his arm felt fine but he’d not been throwing. He said he planned to “cut loose” in a few days.22 It was not until May 13, however, that he made his season debut. He pitched one inning. Edward Burns wrote that Stratton was not “a sensational success, but the fact that he was back in there” was a good sign.23

Eleven days later he made his first start of the season and went the distance for the win, which, according to Burns, convinced observers that he would be as good as he was the previous season. Two weeks later, Stratton was said to be in “superb form” as he hurled another victory.24 At the All-Star break, although not selected to the All-Star team, Stratton was 6-3, a great record considering that the White Sox were decimated by injuries. After the All-Star break, Stratton defeated the Yankees at Yankee Stadium, and came back to beat them again later in the season. He finished the 1938 season with 15 wins, “an impressive total for a man who missed seven weeks of the race,” noted Vaughn.25 He lost nine games, walked just 56 batters in 186⅓ innings, and posted a 4.01 ERA.

Once again Stratton headed back to Texas for the winter. During Thanksgiving weekend he drove his wife and child to spend the holiday with his family on his mother’s farm, “Where we were all born,” said his brother Hardin.26 It was a big weekend for Monty and Ethel, as Monty Jr. would be one year old on November 28. On the 27th, Stratton decided to take a stroll by himself near the farm and hunt rabbits with a .22 caliber pistol he had purchased the previous summer in Chicago. While he wandered along a path a half-mile from the house, he spotted a rabbit just ahead. He took out the gun, fired, and then, “Monty stuck the gun in his holster and thought he had it on ‘safety,’ but it wasn’t,” according to Hardin Stratton.27 The gun fired and a bullet entered Stratton’s right thigh and settled behind the knee. He fell to the ground in pain.

Unable to walk, he yelled for help, but he was too far for anyone to hear. “That was 12:30 Sunday afternoon. Monty started crawling to the house, but it wasn’t until a half-hour later that Leslie (another brother) heard him,” recalled Hardin.28 Ethel also heard him, and saw him frantically wave.29 “Then we took him (by car) to the hospital in Greenville, 10 miles away”30

At the small Greenville hospital, the bullet was located and removed. Stratton was then transported in a birdsong-sorrells ambulance.31 At 6:30 that evening, the Strattons arrived at St. Paul Hospital in Dallas. Dr. Arthur Thomasson and his staff immediately went to work. The medical staff located the bullet and removed it. They tied the artery and began blood transfusions. “There was a complete severance of the popliteal artery behind the right knee, cutting off all blood supply to the lower leg,” said Dr. Thomasson, who knew that collateral circulation was needed in order to prevent gangrene from setting in.32

The news of Stratton’s accident quickly spread on the news wires and reached the White Sox. “We are communicating with our scout, Bob Tarlton, who is in Dallas,” said White Sox secretary Harry Grabiner. “It is unfortunate, for Monty was one of the best pitchers in the American League. But baseball is secondary now. Our concern is about his health. We are hoping nothing more serious develops.”33

The news the next morning was not good. “Collateral circulation failed to set up and gangrene set in,” Dr. Thomasson said. “The leg turned black this morning, making the operation (amputation) imperative.”34 At 4:10 P.M. Stratton was placed under anesthetic, then went into surgery under the guidance of Thomasson and three other doctors. Seventy minutes later, the operation was over. When asked how he was doing, a nurse replied, “As well as expected.”35

Four days later, an unidentified newsman was admitted to Stratton’s hospital room, where he found the pitcher smoking a cigarette and reading a newspaper. Stratton told him he was “feeling normal again,” and that he had shaved earlier that day for the first time since the accident. “It’s been tough lying here, knowing that my baseball career is over,” he said. ”But I am alive and have my wife and youngster and friends. What more could a man want?” He also said he was amazed about the overwhelming support he was getting in the form of letters and telegrams. “I never knew I had so many friends. Fans, teammates and fellows I played against all wrote me. It’s great to have friends.”36

One week later the White Sox announced that Stratton would have a job with their team. “Monty has a job with us as long as he wants,” said team owner Lou Comiskey.37 “The White Sox are happy to do anything possible for a member of the organization struck down in his prime.”38 It was assumed that Stratton would work in the team’s front office, but the indefatigable Stratton had other ideas about his future, and what he wanted was to return to the diamond. “If it can be done, I’ll do it,” he said.39

As Stratton recovered at the hospital, support continued to pour in. “I received about 15,000 letters from men, women, and children in every state of the Union. On Christmas Day I had 815 pieces of mail. It made me feel great. There was never a time when I was completely down in spirits.”40 He was fitted with an artificial leg made of wood, and with the help of a cane, he checked out of the hospital. Two weeks later, Stratton threw away the cane. He traveled with his wife and child to visit his in-laws in Omaha. While in Nebraska, he said he hoped to pitch for the White Sox in a scheduled exhibition game in April against the Cubs. He said he was playing catch with his wife, but was just lobbing the ball. He mentioned that he hoped to cut loose when the weather got warmer. When asked about his handicap to field his position, Stratton said he believed he could hold his own. He mentioned that his biggest problem would be running to first base.41

When the 1939 season began, Stratton was on the job, but not as a front-office employee. He’d become a member of the White Sox coaching staff and was serving as the team’s batting-practice pitcher. To reporters he expressed his dream of returning to the game as a pitcher. “It will take time,” he said. “By the end of the season, I will know for sure.”42 He was unable to pitch in the Cubs-White Sox exhibition as he hoped. As a nice gesture, the Cubs and White Sox agreed to give Stratton the game’s gate receipts, plus the totals from concessions and parking, which combined with the gate receipts, totaled $29,845.25.43

Stratton kept his heart set on being able to pitch in a game during the season. Manager Jimmy Dykes heard his repeated request but feared that opposing teams would “bunt him brutally.”44Dykes promised Stratton that he could pitch on the last day of the season if the White Sox had third place clinched, but when that time came the White Sox were in fourth place, not third, and Stratton never got his chance.

After the 1940 season, Ethel gave birth to another boy, Dennis. At this point, after two seasons as a coach, Stratton returned to the farming life in Texas, but did not lose sight of returning to the pitcher’s mound. “After I left the White Sox, I still wanted to pitch,” he said. “My wife kept saying, ‘if only we could find someone who will give you a chance. I just know you could win a lot of games.’”45 Stratton stayed in shape by pitching to his wife, throwing against the barn and practicing coordination in his living room.

When the United States entered World War II in December 1941, Stratton attempted to enlist in the Army, but was rejected. A few weeks later, the offer he and his wife had hoped for arrived when the Lubbock (Texas) Hubbers of the West Texas-New Mexico League contacted him about pitching and managing the team in what was termed as an experiment. “I was mighty nervous,” Stratton admitted about his first game managing Lubbock, “but the first inning wasn’t so bad as I thought would be.”46 The league suspended its season in July, but Stratton was still determined to pitch. In order to continue, “our town got up a team. With all the able bodied fellows off to war, we didn’t have much to choose from,” said Stratton.47

After the 1942 season, Stratton was idle from baseball until he received an invitation three years later. “There was a semipro tournament goin’ on in Houston and a writer was lookin’ for a pitcher who could win one game for his team. He wanted to know if I could recommend somebody. I showed the letter to my wife and all day while I was workin’ (on the farm) I was tryin’ to think of someone. Well, I got home that night, and my wife told me she’d suggested me. ‘Honey, you know that they don’t want me,’ I said. But they did, and I went down there and was lucky enough to pitch a two-hitter and at the same time make a hit against the other team that drove in the only two runs of the game.”48

In 1946 the Class-C East Texas League resumed operations after the end of the war, and started looking for players. Stratton wrote to the Sherman team, and Guy Sturdy, the manager, invited him for a tryout. After watching the veteran pitcher throw a few, the manager not only signed Stratton, he predicted that he would win 25 games. In his first game the delighted Stratton hurled a 6-4 win before 2,000 fans who marveled at his ability to field. He had three assists and a putout and participated in a double play, while striking out 11. He also got a clean hit to center field, but as he limped his way to first base, his leg buckled. He tried to crawl to first base, but was thrown out by a few feet. After that the league inserted a courtesy-runner rule for Stratton for anytime he got on base.49

In Stratton’s next game he fanned nine batters, allowed no walks, and pitched six perfect innings before allowing a hit in the seventh inning in a 6-1 win. By the season’s halfway point he had 11 wins, and he went on to win 18 in all. The Philadelphia Sportswriters Association named him the recipient of the 1946 Most Courageous Athlete Award

“Monty, now all you need to make your life complete is have Hollywood make a picture about you,” Ethel told him.50 Others were thinking along the same line. “I was wondering the other day why a picture hadn’t been done about the one-legged pitcher, Monty Stratton,” wrote syndicated gossip columnist Hedda Hopper.51

In 1947 Stratton moved up a level to Class B at Waco, Texas, of the Big State League, where he posted a 7-7 record. A year later, the Strattons went to Hollywood to watch the making of the movie about his life, The Stratton Story (1949), directed by Sam Wood and starring Jimmy Stewart and June Allyson. While serving as an adviser on the set, Stratton also received $100,000 for his story.52

Stratton loved his time in Hollywood but admitted that he missed Texas and the farming life. He intended to retire from baseball, but his love for the game kept him active for a few more seasons. “Spring comes around and the grass gets green and baseball gets into your blood, I guess,” said Stratton.53 Another reason for his decision to continue to pitch was that the movie was a box-office hit and made him something of a celebrity. “A lot of people wanted to see me (pitch),” Stratton said.54 He pitched in 14 games over the course of the next five seasons for various minor-league teams in Texas before packing it in as a professional.

Stratton continued to work on his farm with the same dexterity that he displayed during his remarkable pitching comeback. He drove a car and occasionally played catch with Ethel. He said he was never bothered by the loss of his major-league career or the artificial leg. “It now feels as if I was born with it,” he said.55 In 1961 Stratton was inducted into the Texas Sports Hall of Fame. A few years later he endured another tragedy when his son Dennis was found dead from a self-inflicted gunshot wound.

In 1980 Stratton received one more honor when he was inducted into the Texas Baseball Hall of Fame. A year later he was diagnosed with cancer, and he knew the end was near. “I was with my father the last week of his life,” said Monty Jr., who worked several years for McDonnell Douglas Corporation in St. Louis. “He knew what was going on. He had no fear. One night he said he hoped that in lieu of flowers or some other remembrance, perhaps some memorial could be enshrined, maybe at a children’s hospital. He thought it might serve as an inspiration to some youngster fearing a dismal future because of a loss of an arm or leg.”56

Monty Stratton died on September 29, 1982, at the age of 70. He was buried at Memoryland Memorial Park in Greenville, Texas.

Notes

1 Philadelphia Inquirer, August 1, 1937.

2 Chicago Daily News, November 30, 1938.

3 Chicago Daily News, November 30, 1938.

4 Unidentified newspaper article found in the Monty Stratton player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame’s Giamatti Research Center, Cooperstown, New York.

5 Unidentified newspaper press release, January 16, 1938, in Stratton file.

6 Unidentified newspaper clipping dated August 22, 1935, in Stratton file.

7 John Carmichael, “The Barber,” 1937 article in Stratton file.

8 Chicago Daily News, November 30, 1938.

9 Unidentified newspaper in Stratton file.

10 Chicago Tribune, June 3, 1934. It was 3⅓ innings, to be more precise.

11 Omaha World-Herald, August 5, 1934.

12 New York Times, April 24, 1949.

13 St. Paul Press, April 9, 1935.

14 St. Paul Press, July 31, 1935.

15 Chicago Tribune, September 8, 1935.

16 Chicago Tribune, September 23, 1935.

17 Chicago Tribune, April 3, 1936.

18 Chicago Tribune, April 11, 1936.

19 Chicago Tribune, May 8, 1936.

20 Chicago Tribune, April 23, 1937.

21 Chicago Tribune, October 4, 1937.

22 Chicago Tribune, April 7, 1938.

23 Chicago Tribune, May 14, 1938.

24 Chicago Tribune, June 3, 1938.

25 Chicago Tribune, September 21, 1938.

26 Harold Sheldon, “Finishing the Stratton Story,” Baseball Digest, September 1949.

27 Sheldon.

28 Sheldon.

29 Undated Chicago Daily News article in Stratton file.

30 Sheldon.

31 Associated Press, “Monty Stratton, Ace of White Sox Staff, is Hurt in Hunting Accident,” Greenville Morning Herald, November 29, 1938: 1.

32 Sheldon.

33 Chicago Tribune, November 28, 1938.

34 Chicago Tribune, November 29, 1938.

35 Chicago Tribune, November 29, 1938.

36 Chicago Tribune, December 23, 1938.

37 Brooklyn Eagle, December 11, 1938

38 Chicago Tribune, December 11, 1938.

39 Chicago Tribune, April 7, 1939.

40 Unidentified newspaper article dated April 20, 1939, in Stratton file.

41 Chicago Tribune, April 7, 1939.

42 Unidentified newspaper article dated April 20, 1939, in Stratton file.

43 Chicago Tribune, May 2, 1939.

44 Sheldon.

45 Philadelphia Inquirer, January 30, 1947.

46 L.H. Addington, “Monty Stratton’s Courageous Comeback,” June 1947 article, soiurce unidentified, in the Stratton file.

47 Philadelphia Inquirer, January 30, 1947.

48 Philadelphia Inquirer, January 30, 1947.

49 Addington.

50 New York Times, April 24, 1949.

51 Chicago Tribune, December 23, 1946

52 Washington Post, September 7, 1947.

53 Los Angeles Times, June 19, 1950.

54 Unidentified newspaper article, July 14, 1974, in Stratton file. For more detailed information on the making of The Stratton Story: Rob Edelman, “Of Black Sox, Ball Yards, and Monty Stratton: Chicago Baseball Movies,” in North Side, South Side, All Around the Town: Baseball in Chicago (The National Pastime, SABR, 2015).

55 New York Times, April 24, 1949.

56 St. Louis Globe-Democrat, October 28, 1982.

Full Name

Monty Franklin Pierce Stratton

Born

May 21, 1912 at Wagner, TX (USA)

Died

September 29, 1982 at Greenville, TX (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.