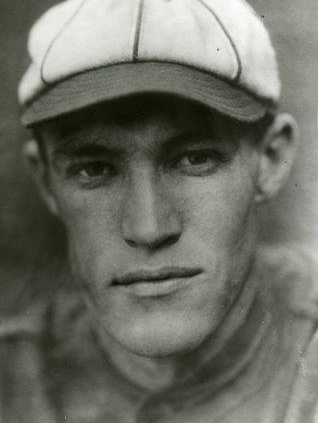

Al Kaiser

In his short major-league career, Albert Edward Kaiser played only 155 games and batted only .216. Yet from 1909 through 1914, he was known in the Midwest as an exceptionally fast outfielder, daring baserunner, and somewhat reckless player. In fact the Indianapolis Star, reviewing the 1913 season, said that “his great speed enabled him to shine as a baserunner and his feats on the base paths won for him the nom de diamond of the ‘Ty Cobb of the Feds.’”1 Earlier, the Indianapolis News declared that Kaiser’s speed demonstrated “that Ty Cobb did not have anything on him Monday when he went from 1st to 3rd on [a] sacrifice bunt, emulating the Georgia [P]each also in his slide into the far corner.”2

In his short major-league career, Albert Edward Kaiser played only 155 games and batted only .216. Yet from 1909 through 1914, he was known in the Midwest as an exceptionally fast outfielder, daring baserunner, and somewhat reckless player. In fact the Indianapolis Star, reviewing the 1913 season, said that “his great speed enabled him to shine as a baserunner and his feats on the base paths won for him the nom de diamond of the ‘Ty Cobb of the Feds.’”1 Earlier, the Indianapolis News declared that Kaiser’s speed demonstrated “that Ty Cobb did not have anything on him Monday when he went from 1st to 3rd on [a] sacrifice bunt, emulating the Georgia [P]each also in his slide into the far corner.”2

Though Kaiser had nothing of Cobb’s fierce anger and controversy, newspaper accounts of his games invariably stressed the exceptional quality of his play, many of his attempts in the outfield being noteworthy, occasionally leading to his being hurt or misplaying a ball in a disastrous way. Unlike many of the ordinary players of his time, the press often made his exploits stand out. Baseball-Reference.com lists his nickname as Deerfoot, and otherwise he was called Germany Kaiser, Fritz, and other monikers.

Of course, Kaiser played in the years in which Kaiser Wilhelm was frequently in the news, sometimes as an amusing comic-opera character or as a very powerful and dangerous monarch, and after August 1914 as a villain or misjudged victim, depending upon one’s nationality. Alfred Edward Kaiser was born August 3, 1886, in Cincinnati, son of German immigrants Dora and Henry Kaiser, a brickyard laborer. He grew up among a large German population and often returned to that area in Cincinnati.

Kaiser began his baseball career playing semipro ball in Cincinnati’s West End. He played left field for the Cincinnati Shamrocks of the KIO League and possibly other teams.3 On September 2, 1908, the Shamrocks sent Kaiser to Dayton of the Central League to replace a player called up by the Reds. On September 6 vs. Fort Wayne, left fielder Kaiser stole a base and took part in a double play.4

From the first, Kaiser made news, intervening in a purse-snatching, and receiving “a badly battered mug” from “a bunch of thugs” but getting overpowered “by force of numbers and beaten up.”5 His eye was blackened “but he got on the ball all right in the seventh inning” – a foreshadowing of his 30-year career as a crime fighter later in Cincinnati.

In five games for the 1908 Dayton Veterans, Kaiser had only two hits, batting. 133. The next year, in his first full season as a minor leaguer, Kaiser shared 98 games between Lexington and Paris of the Blue Grass League. Again touted as among the fastest to ever try to break into the league, he hit .257 and fielded .927. In about a third of the 20 or so games covered in the Louisville Courier-Journal, Kaiser is mentioned for fine fielding and strong play.

Playing for the Paris Bourbonites in 1910, Kaiser came to the attention of major-league scouts and managers. He played in 111 games, batted 429 times, and had 136 hits, with 23 doubles and 12 triples. His .317 batting average – highest of his career – was the third-highest in the Blue Grass League. The Bourbonites finished 80-47, .630, winning the league title by 10 games.

Kaiser started 1910 as a holdout, with two other teammates delaying so long that club President Bacon said it was paying all the salary it could afford and unless contracts were received shortly he would dispose of the trio to other clubs or refuse to grant them a release, which would deny them the privilege of playing in Organized Baseball.6 On March 10, 1910, Kaiser returned his signed contract, writing that he was in “splendid health and expects to play the finest games this year that he has during his career on the diamond.” The Bourbon News commented that “Kaiser did good work with Paris last season and made many friends, who will be glad to learn of his return.”7

When play started, Kaiser did indeed show that he was ready to perform: On April 23 against Clintonville he “played a brilliant game in the field, secured three hits and by fast sprinting scored three runs and had to his credit four stolen bases”; the next day, against the Hustlers of Cincinnati, he went 4-for-5 with a triple;8 on May 11 he hit a home run against Richmond;9 and on June 3 he was hitting .364.10

In the second half of the season, Kaiser continued his outstanding play. Notably, on July 2 he scored from first base on a single to right field.11 Later that month, “Germany” Kaiser so befuddled fans in Lexington, handling seven chances “without a bobble” that, according to the Bourbon News, fans have “taken such a fancy to the outfielder that they are really calling him pet names.”12

His reputation was such that on September 6 the Chicago Cubs drafted him for the 1911 season, assigning him to their American Association affiliate in Louisville.13 To close out this season of great success, the Bourbonites clinched the pennant in a 16-inning game against Lexington on September 20, and the next day in a benefit game and contest, Kaiser excelled in the long throw (375 feet), the sprint from home to first (3.25 seconds), and the 100-yard dash (10.5 seconds). That same week he was selected to the league all-star team by the Lexington Leader.14

In the early spring of 1911, Kaiser began playing practice and exhibition games at Louisville. Manager Bacon of his former team, the Bourbonites, told the Louisville owners that if they didn’t want Kaiser, then the Paris club would eagerly take him back. However, the Louisville Courier-Journal observed that the young player had made such a remarkable showing in the practice games that he would more than probably fill a regular berth with the Colonels.15 In fact, when the Cubs visited for exhibition games, it was clear that Kaiser would not remain long at Louisville: The Chicago Tribune on April 3 remarked that he would be a “Hummer” if he played in the National League, and on April 10 that Kaiser “can run around the bases as fast as [Heinie] Zimmerman and seems to increase the speed with every stride. … In the field he can cover as much ground as Artie Hofman16 himself, and he can throw from any position and shoot the ball in like a bullet. All he needs is a bit of polishing in the finer points of the game, and he’ll get that while doing base duty.”17

Within a week of these statements, Kaiser became a member of the Chicago Cubs. The Chicago Inter Ocean reported that “there is great rejoicing in the Cub camp over the wonderful showing being made by outfielder Kaiser, who is been subbing in Hofman’s place.” It was, according to the newspaper, an excellent recommendation of manager Frank Chance’s judgment.18

During his short time with the Cubs, Kaiser and his teammate Heinie Zimmerman made history as they both stole home in the seventh inning of a game against Brooklyn on June 7.19

Throughout May and early June of 1911, Kaiser’s play was inconsistent. He had occasional two-hit games and a few extra-base hits along with some extraordinary plays in the outfield, but when he made errors, they were usually disastrous: In an important game against the Giants he let a single get past him that rolled into the crowd for a four-base error and later in the same game dropped a fly ball.20 These were the plays that the manager remembered when the Boston Rustlers came to Chicago the second week of June. On June 7, though, Kaiser and his teammate Heinie Zimmerman both stole home in the seventh inning of a game against Brooklyn on June 7.21

Four days later, on June 11, the lead baseball story all over the country was the eight-player swap between the Cubs and the Rustlers that was made the day before. Fans in both cities were shocked, and Boston was especially outraged. The fact that the exchange took place while the teams were playing each other led to confusion when the Chicago fans saw four of their favorites wearing the uniform of the opposition and at the same time unfamiliar players wearing Cubs outfits. Impetus for the exchange was that Cubs manager Chance would be out of commission for perhaps the rest of the season because of an eyesight problem. It was necessary to obtain an experienced first baseman to replace Chance, and Boston’s Wilbur Good seemed the best available. Boston would trade Good only for Chicago’s Johnny Kling, which would leave the Cubs with only one healthy catcher. So Boston catcher Peaches Graham became part of the deal, and Kaiser went to Boston to fill the slot left by Good. Chicago’s Orlie Weaver and Boston’s Bill Collins exchanged teams to complete the deal.22

Parting with Johnny Kling, a Cub since 1900 and a mainstay behind the plate up through 1908, offended some Cub fans, As for Kaiser, Good could fill the gap in center better and was less error-prone. In Boston’s reaction, L.C. Page, one of the team’s directors, protested and instructed attorneys to bring suit against Boston President William Russell, saying, “[W]e don’t want Kling at any price. To give a clever, all-around man like Graham is simply an insult to the Boston baseball public. … Now, what do we get? – A lot of junk that Chicago has no use for.”23

The Inter Ocean wrote that Kaiser played remarkable baseball when the Cubs played in Boston: “[H]e was hitting and judging flyballs like a star. [Boston manager Fred] Tenney liked him just as Chance did when he first clamped eyes upon him, but unlike Chance, Tenney hadn’t seen the recruit from Louisville misjudge flyballs and play like a novice in the garden in the position deserted by Artie Hofman. They wanted Kaiser.”24

Contrary to the Inter Ocean’s remark, Boston did not particularly want Kaiser if one can judge from the newspaper accounts. Part of the reason may be that the fans so disliked giving up Good and Graham that they were hypercritical of Kaiser, unfair as that might be. And also, as the year went along, Kaiser hit much worse with the Rustlers than he did with the Cubs. From June 10 through October 9, he played in 66 games, started 48, had 217 plate appearances, and batted only .203 with 15 RBIs. The Boston Globe remarked that “Kaiser the outfielder handed over to Boston has shown little this year to commend him while Boston parted with Collins, a fine fielder but a very light batsman, and Good a first-class man.”25

Kaiser was not in Boston for the first game after the trade because he had been granted permission to go to Cincinnati to be with his sick wife. Afterward, he had few memorable games for the rest of the season. On June 30 he doubled in a win over New York;26 on July 5 he hit a home run in a game in which he was 3-for-4; on July 7, batting cleanup, he had a two-run homer in a 5-4 victory over Cincinnati; on July 14 against the Cardinals, he was 2-for-4 with a stolen base; and on September 12 he had three hits in a doubleheader, playing before the largest crowd of the season, 10,659. There were fewer memorable days also, and they seem to be stressed: On July 6 in a 12-inning loss to Cincinnati, Kaiser batted with the bases loaded and hit into a double play;27 on July 22 against Pittsburgh, he dropped a fly ball, allowing a score;28 and on July 26 he went hitless in a doubleheader against the hated Cubs.29 Most telling, against the Cardinals in the ninth inning with two outs and the bases loaded, Kaiser caught a hard liner in deep left, yet the Globe sportswriter maintained that with “a little variation of the left or right in the field he would not have been able to catch it and the bases would have been cleared,” giving him no credit for the catch. This was a game in which Kaiser went 2-for-4 with a stolen base.30 In August and September, he was primarily a pinch-hitter. He played through October 9.

Among a group of five outfielders, Al Kaiser went to Augusta for spring training with the Braves to start the 1912 season. On April 2 in an exhibition game against Richmond, he had two hits in five trips and scored two runs.31 These were the only hits he got the rest of his time with Boston: In four regular-season games, he was 0-for-13. On April 21, according to the Globe, the Rustlers all played fine baseball, “except for Kaiser, who had all sorts of trouble with the balls that came his way.”32 Five days later Boston sold Kaiser to the Indianapolis Indians of the American Association.33

Instead of reporting to Indianapolis as expected, Kaiser went home to Cincinnati, holding out for more money. To the shock of most observers, he turned down a $300-a-month raise, up 20 percent from the $250 paid by Boston. Neither the Boston nor the Indianapolis newspapers could believe that he was not satisfied with the $50 more paid by a minor-league team over a major-league organization. An angry Indianapolis manager Jimmy Burke responded, “If Kaiser wished to come back, I will use him if I have a place for him then, but his departure is not worrying me.”34

Kaiser eventually joined the Indians. In three weeks in May he had several two-hit games, but a summer of injuries began on June 7 when he damaged some ligaments sliding home, and then went home to Cincinnati to recuperate. Back within two weeks, he reinjured himself and played sparingly throughout July; even so, through 43 games as of July 13 he had 157 at-bats, stole 10 bases, and was batting .287.

By mid-August, Kaiser was back in uniform, hoping to be recalled by Boston. His treatment by the local press was beginning to be less favorable; the Indianapolis News, while reporting on a bases-clearing triple, led with this statement: “Al Kaiser, who is always been more or less erratic, upset the dope when he cleaned the sacks with a smashing triple to center.”35 This erratic behavior was further revealed when club President Sol Meyer suspended him because he failed to show up at Washington Park for practice.36

Kaiser finished the 1912 season hitting .268 but playing in only 56 games.

Kaiser’s chances to return to Boston in 1913 were slim at best, for before spring training he asked the Braves to pay him the salary he drew in 1912 in Indianapolis. This was, of course, more than he made as major leaguer. Sportswriter H.G. Copeland of the Indianapolis Star wrote that this demand proved how liberal the Indianapolis club was with money and that the request would be a test case to decide “whether a major-league club can reduce the salary paid by minor-league club to a farmed out player when that player returns to his original jurisdiction.”37 On March 27 Boston sold Kaiser’s contract to San Francisco of the Pacific Coast League.38 Seeking a place closer to home, Kaiser became the first player of note to be signed by the Indianapolis Federal League club. (The Federal League did not declare itself a major league until the next season, 1914.) The Indianapolis dailies were mixed in their reaction, with the Star opining, “Al Kaiser joined the federal leaders. Al Kaiser? Oh yes, he’s the fellow who Sol Meyer paid for the privilege of surgical experimenting last summer”39; the News commented that Kaiser “is rated as a speedy fielder and a good hitter, but continual injuries and a more or less this erratic disposition hurt his effectiveness.”40

After the home opener, a 3-2 loss to Chicago before 18,507, the Indianapolis Star commented, “Al Kaiser is doing dandy work for the Federals and looks to be one of the local team’s best cards.”41 In August the club won 13 of 14 games on a road trip, taking first place, not to relinquish it. Kaiser’s most productive day was September 15 in a doubleheader sweep over St. Louis, in which in eight trips to the plate he had five hits and drew three walks, a perfect afternoon.42 The Hoosiers won the pennant by 10 games, and Kaiser batted .286 with 127 hits, 19 doubles, 8 triples, 4 home runs, and 31 stolen bases. It was clearly a very successful year, his most successful overall in professional baseball.

The next season the Federal League emerged into what can be considered a major-league organization, albeit according to the National and the American Leagues “an outlaw league.” At the Hoosiers home opener before 6,000 fans, Kaiser led off to tumultuous applause.43 Playing for the pennant-winning Hoosiers, who finished 88-65, 1½ games ahead of the Chicago Chi-Feds and hit .285 as a team, Kaiser played in 59 games and hit .230. On July 19 he made a game-ending shoestring catch with two outs in the ninth inning and a runner on second base: “Kaiser touring like a racehorse, snared the ball, stumbled, and recovering, held the ball aloft and raced for the clubhouse. It certainly was some finish.”44 On August 9 he won a 13-inning thriller with a pinch-hit single,45 and on August 18 he was part of a double steal against Pittsburgh.46

A fielding play of note occurred on August 4 in a 5-4 loss to Buffalo when Kaiser chased a windblown drive to deep left and caught up to it. But “by leaning over the fence, he managed to hit his head on the wall, but he could not hold it. … No man could have done so. Bouncing away went the ball and with it the ballgame.”47

The most significant event in Kaiser’s 1914 year occurred in spring training in St. Louis when, suffering from a “well-defined attack of acute indigestion, he fainted into a gutter, was taken back to his hotel, confined and then sent home to Cincinnati.”48 Five weeks later he was able to return to play, having recovered from bronchitis. He was never able to regain his old playing strength, and on September 7 he was given 10 days’ notice of his unconditional release. He said he had not been able to play his best game all season and desired to go to his home in Cincinnati.

Existing records indicate that this was the end of Kaiser’s baseball career and that he went very soon into detective work in his hometown of Cincinnati. However, according to the Indianapolis News, he was playing semipro ball for the Kokomo Red Sox in the summer of 191549 and in 1916 came to Indianapolis with the Cincinnati Shamrocks, “one of the crack semi-pro professions in the country.”50 That same summer the Indianapolis Star said that Kaiser had signed with the Rocky Mount club of the Virginia League.51

Kaiser did not immediately go into detective work; according to his registration for the World War I draft in 1917, he was a leather splitter at American Oak Leather Company. On July 5, 1917, he joined the Cincinnati police force and became a member of the detective crime unit in 1925. As a detective working to solve thefts, Kaiser was featured in the Cincinnati Enquirer at least 14 times. Most of the crimes involved small items stolen – shoes, cameras, radios, and suits. Often his investigations would take him to Kentucky (Newport, Louisville, and Lexington), though most of the crimes occurred in downtown Cincinnati and in the more affluent suburbs. At least once he was engaged in a shootout with criminals and several times suffered knife cuts in making arrests.

When Kaiser retired on September 28, 1945, the Cincinnati Enquirer mentioned his baseball career in the Blue Grass League, with Chicago and Boston, and with Indianapolis of the Federal League, and noted that he started his career in Cincinnati’s West End.52

On February 18, 1946, Kaiser’s older of two sons, Alfred Kaiser Jr., suffered life-threatening burns as a result of a pitch pot explosion at the Berger Brewing Company in Cincinnati. He survived.53 On December 22, 1955, his younger son, Francis P. Kaiser, a hero of the Normandy Invasion and, like his father a celebrated amateur baseball player, died of a cerebral hemorrhage during an emergency operation.54

Al Kaiser himself died after a long illness on April 11, 1969, at age 82. He is buried in Old St. Joseph Cemetery beside his wife of 47 years, Marie Alice Wahoff Kaiser.55

Sources

In addition to the source cited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 Indianapolis Star, February 13, 1914: 11. Benjamin Kauff of the 1914 Indianapolis Hoosiers deserves this Ty Cobb comparison more than does Kaiser because Kauff hit much higher in average and stole many more bases with a Cobb-like intimidation of opposing infielders. Thus does Robert Peyton Wiggins, in his book The Federal League of Baseball Clubs: The History of an Outlaw Major League, 1914-1915 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2009) term Kauff “Ty Cobb of the Feds” (135-141). Kaiser receives only three brief mentions in Wiggins’s book.

2 Indianapolis News, May 15, 1912: 13.

3 Cincinnati Enquirer, July 6, 1908: 6. Kaiser, playing left field, went 1-for-4. See also Dayton Herald, July 20, 1908: 8.

4 Cincinnati Enquirer, September 6, 1908: 8.

5 Cincinnati Enquirer, October 26, 1908: 3.

6 “Blue Grass League Notes,” Bourbon News, February 8, 1910: 8.

7 Bourbon News, 11 March 11, 1910: 2.

8 Bourbon News, April 26, 1910: 9.

9 Bourbon News, May 13, 1910: 4.

10 Bourbon News, June 3, 1910: 8.

11 Bourbon News, July 5, 1910: 4.

12 Bourbon News, July 19, 1910: 4.

13 Bourbon News, September 20, 1910: 4.

14 Bourbon News, September 23, 1910: 5.

15 Louisville Courier-Journal, March 25, 1911: 10.

16 Artie Hofman was the player also known as Solly Hofman.

17 Chicago Tribune, April 3, 1911: 4; and April 10, 1911: 17.

18 Chicago Inter Ocean, April 27, 1911: 4.

19 James D. Szalontai, Small Boy in the Big Leagues: The History of Bunting, Walking, and Otherwise Scratching for Runs (Jefferson North Carolina: McFarland, 2010), 53. The Cubs stole home 17 times that season, as did the 1912 Giants. The 1912 Yankees stole home 18 times.

20 Chicago Tribune, June 9, 1911: 9.

21 Szalontai.

22 Handy Andy, “Kling to Boston in Player Swap,” Chicago Tribune, June 11, 1911: C1. This article has a very good explanation of the trade and an analysis of its value.

23 Chicago Tribune, June 11, 1911: C1.

24 Chicago Inter Ocean, June 11, 1911: 24.

25 Boston Globe, June 14, 1911: 7.

26 The following accounts for the summer of 1911 are all from the Boston Globe: July 1, 1911: 3; July 6, 1911: 7; July 8, 1911: 9; July 15, 1911: 9; and September 13, 1911: 7.

27 Boston Globe, July 7, 1911: 7.

28 Boston Globe, July 23, 1911: 14.

29 Boston Globe, July 27, 1911: 7.

30 Boston Globe, July 15, 1911: 9.

31 Boston Globe, April 3, 1912: 7.

32 Boston Globe, April 21, 1912: 14.

33 Boston Globe, April 26, 1912: 20.

34 Indianapolis Star, April 29, 1912: 4.

35 Indianapolis News, September 6, 1912: 16.

36 Indianapolis News, September 14, 1912: 9.

37 Indianapolis Star, February 1, 1913: 8.

38 The Sporting News, March 27, 1913: 5.

39 Fred Turbyville, “The Passing Show,” Indianapolis Star, April 27, 1913: 50.

40 Indianapolis News, May 3, 1913: 11.

41 Indianapolis Star, May 12, 1913: 8.

42 Indianapolis News, September 15, 1913: 10.

43 Wiggins, 11-12.

44 Indianapolis Star, July 19, 1914: 41.

45 Indianapolis Star, August 10, 1914: 8.

46 Indianapolis Star, August 19, 1914: 6.

47 Indianapolis Star, August 5, 1914: 6.

48 Indianapolis Star, April 16, 1914: 6.

49 Indianapolis News, August 2, 1915: 8.

50 Indianapolis News, May 13, 1916: 10.

51 Indianapolis Star, July 10, 1916: 14.

52 “Veteran Sleuth Retires,” Cincinnati Enquirer, September 29, 1945: 18.

53 Cincinnati Enquirer, February 19, 1946: 12.

54 Cincinnati Enquirer, December 22, 1955: 38.

55 Cincinnati Enquirer, April 12, 1969: 24.

Full Name

Alfred Edward Kaiser

Born

August 3, 1886 at Cincinnati, OH (USA)

Died

April 11, 1969 at Cincinnati, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.