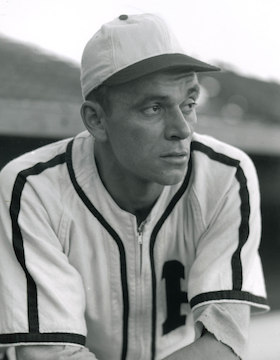

Al Papai

Right-handed knuckleball pitcher Al Papai earned many more accolades serving four years in the United States Army during World War II than he did in four years of appearances in major-league baseball.

Right-handed knuckleball pitcher Al Papai earned many more accolades serving four years in the United States Army during World War II than he did in four years of appearances in major-league baseball.

He was one of the 11 children of Illinois coal miner Victor Papai and his wife, Mary, the former Marie Pongracz. Both were immigrants from Hungary, Victor was from Rabapatona, Gyor-Moson-Sopron. He arrived in the United States in 1901 and Marie arrived in 1903. The couple became naturalized American citizens in 1910. Alfred Thomas Papai was the ninth of their children, born in Divernon, Illinois, on May 7, 1917. Divernon is more or less 20 miles due south from Springfield, Illinois. The family name was said to be pronounced “Poppy.”1

Al attended Divernon High School, graduating in 1937. Victor Papai saw every one of his children graduate from high school. Al learned to throw a knuckler while still on the sandlots. He played semipro baseball in the area, playing for the Emerson Cigars and Fitzpatrick Lumberjacks teams in Springfield. He took up work as a plumber’s helper, but was probably destined for the coal mines. Two of his older brothers had followed their father into the mines. “I suppose that’s where I would have gone, if it hadn’t been for baseball,” he said 10 years later.2 That same year, however, Al’s talent at baseball got him a job in the St. Louis Cardinals farm system. Papai was listed at 185 pounds and stood 6-feet-3.

Papai was friends with Ted Novak, who had pitched for the Northern League’s Duluth Dukes in 1938 and 1939. Novak “talked me into going into spring training with Duluth. I signed a Duluth contract in Springfield, Ill. and I went to spring training at Springfield, Mo. as a member of the Duluth club. I was reassigned to the Worthington ball club.”3 He spent 1940 pitching for the Worthington (Minnesota) Cardinals in the Class-D Western League.

It was a successful first season in the pros; Papai had a 3.36 earned run average and a 12-10 record. He was bumped up to Class C in 1941, pitching for the Springfield (Illinois) Cardinals (Western Association), where it was a little tougher. He worked in 21 games with a record of 7-6 (5.30). His season was cut short in July by a call from Uncle Sam. Normally, he might have benefitted from another year of development at Class C ball, but the United States was headed toward war and Papai was inducted into the United States Army, where he served in the infantry from July 1941 until June 1945. He therefore missed most of the next four seasons of baseball.

In fact, the league didn’t play baseball, either; after 1942, the Western Association disbanded for the duration of the war. Papai’s contract was assigned to Lynchburg.

Papai served in North Africa – Tunisia, Morocco, and Algeria, in Sicily, Normandy, Rhineland, and Central Europe. And he saw front-line action. He received three bronze battle stars, a Silver Star, and a Purple Heart, as well as five overseas service bars.4 With the end of the war in the European Theater on V-E Day (May 8), he was mustered out the following month and returned home.

He arrived in time to return to baseball. He pitched in Class B ball, appearing in 11 games for the Lynchburg Cardinals (4-5, with his 2.39 ERA showing he had by no means lost his skills on the battlefield.) Near the end of the season, he appeared in seven games for Allentown (1-2) but was brought back to Lynchburg.

He pitched for Lynchburg again in 1946, with a 15-11 record and a stellar 2.31 ERA for the last-place Cardinals. One of his better games was the 2-1 three-hitter he threw against Richmond on August 12. At the end of the season, he was a unanimous selection to the Piedmont League’s All-Star team.5

But it wasn’t his best season. That came in 1947.

Recalled to St. Louis on August 31, 1946, he was optioned to Houston in the AA Texas League in April 1947, and became a 20-game winner for the first of four times in his career.

He was 21-10 with a 2.45 ERA and a league-leading 24 complete games. Houston won the pennant and both rounds of the league playoffs; he threw a one-hitter in the first playoff game, against Dallas on September 17. Manager Johnny Keane was asked what he thought was the main factor in placing first. He said, “Al Papai. During the past six weeks, his pitching was nothing short of sensational. Then Clarence Beers, who all year long was very dependable.”6

Houston then took on the Mobile Bears in the Dixie Series, the Texas League champion against the Southern Association champion. Papai won two games; the Buffs won the series in six games.

Papai went to spring training with the St. Louis Cardinals in 1948 and made the team, working out of the bullpen. His major-league debut came on April 24 at Wrigley Field. The Cubs had a 5-2 lead after 7½ innings. Manager Eddie Dyer asked Papai to pitch the eighth. He got the first batter he faced, but then Hal Jeffcoat hit a solo home run. It was the only hit Papai gave up. He walked a batter, induced a force out to get the runner at second base, then threw to Marty Marion at shortstop to cut down the runner attempting to steal second.

He appeared in three games in May and four in June. His only decision with the Cardinals came on July 6. The Cubs were up, 10-7, at Sportsman’s Park. He set them down in order in the top of the seventh and the Cardinals tied it up in the bottom of the inning. In the top of the eighth, he allowed a double, followed by a sacrifice, a wild pitch, and a home run by Bill Nicholson. The Cubs won, 12-10. His best outing of all was his last one, on July 18, when he worked four innings of one-hit relief. He’d pitched in 10 games, all in relief, with an overall 5.06 ERA. Four days later, he was optioned to the Rochester Red Wings, where he started in each of the 12 games he worked, with a 5-6 record (4.37).

In 1949 the Cardinals optioned him to Houston again, but Commissioner Happy Chandler advised the Cardinals in mid-April that they would lose rights to him if they did so. It would have been his fourth option, and he would thus become a free agent.7 Papai sat on the St. Louis Cardinals bench for the first few weeks of the season before being placed on waivers; he was claimed by the St. Louis Browns on May 9. Asked why the Cardinals’ Eddie Dyer had never started him, he said he didn’t know. “I figured that he knew I was on the ball club, and it was his business to give me a shot at a starting assignment. But he never got around to that.”8

His home games were still played at Sportsman’s Park (the same bench), but he was now in a Browns uniform. For the Browns, he was put to work. He started and pitched complete games in his first two efforts. He was 1-1, despite walking 10 batters in 17 innings in the two games.

His time with the Browns saw him work in 42 games (15 starts) and post the identical 5.06 ERA he had posted with the Cardinals the year before. He was 4-11. His best game, though, was one without a decision, on August 7 at Yankee Stadium, a 10-inning, two-hitter that ended as a 2-2 tie game, called because of darkness and because the rules prohibited turning on lights in mid-game.

As a batter, Papai had a discerning eye, drawing six bases on balls in 45 plate appearances in 1949. He didn’t hit much, however, batting just .079 that year with one RBI. His career batting average was .097.

Every so often, you hear about a team wanting to get younger, maybe adopting a “youth movement.” The Browns arguably went a little over the top in October 1949; they announced that every player on the team over the age of 28 was on the block.9 Players under 28 were not for sale. Papai was 32.

Before the winter meeting, the Browns made him available on waivers and he was selected by the Boston Red Sox for the $10,000 waiver price. The Sox had lost the 1949 pennant on the last day of the season, and might have won at least one or two more games had they had a better bullpen. Papai was at least intended to give them a little more depth in the pen. As for himself, he wanted to win a spot in the starting rotation. “I’m not a relief pitcher,” he told the Boston Herald. “Never was, and I intend to do my utmost to win a starting assignment with the Red Sox this year. I like to work, and pitch much better when I am in there every three or four days.”10

Sox catcher Birdie Tebbetts was pleased with the acquisition. “He’s a dog,” said Tebbetts. “That’s the best way I know to describe him. He gets in there and never lets go. He bears down and throws his heart with every pitch.”11

He was fortunate to go 4-2 with the Red Sox in the first half of the 1950 season; the 1950 Red Sox scored a franchise record 1,027 runs. In a 3-0 loss on April 24, the Senators scored three runs on a walk, one hit, and a couple of miscues; though not a ball had left the infield. Papai lost the game, 3-0. The four games he won were by scores of 6-2, 13-12, 11-9, and 22-14. The last of the four games, his last with the Red Sox, was on July 2. Three days later, with a 6.75 ERA, he was placed on waivers and found himself on his way back to St. Louis, to the Cardinals. He was one of four players the Red Sox disposed of all on the same day in an effort to shake up the team.12

With the Cards in the second half of 1950, Papai was undefeated (1-0), with a 5.21 ERA.

The next three years were spent in the Texas League, again with the Houston Buffaloes. One could well argue that Double-A ball was the level for which Papai was best suited. He was 23-9 with a 2.51 ERA in 1951. The Buffs placed first by 13½ games and won the playoffs. Papai’s 23 wins led the league. Birmingham beat the Buffs in six games to win the Dixie Series.

From the top to the bottom, Houston finished last in 1952. Papai’s 3.04 ERA was very good, but with the team lacking so much else he was fortunate to finish with a winning record, 14-13. In 1953, he did not (11-16, 3.68). The team had worked its way up to sixth place. He pitched in the Venezuela Winter League in 1952-53.

He may have had the opportunity to move up to Triple A and play for Rochester in 1954, but he reportedly didn’t want to move up. “Now they want him to toil for Rochester,” wrote the Springfield newspaper, “but Al prefers to remain in Texas.”13 That wasn’t in the cards, though he did appear in one game for Rochester. On May 5, he was back in the Texas League, if not in Texas itself. His contract was sold to the Oklahoma City Indians.14 For Oklahoma City, he was 11-11 (4.24).

In 1955 he was a 20-game winner once more, 23-7 for Oklahoma City (2.65 ERA), despite the Indians finishing seventh and only winning 70 games as a team. On August 31 his contract was sold to the Chicago White Sox, who were in contention in the American League. It was his first time in the majors since 1950. He relieved in seven September games and acquitted himself reasonably well, with a 3.86 ERA and no decisions in 11⅔ innings.

Late in March 1956, the White Sox released Papai to Memphis. He won 20 games again, 20-10 (3.69) in Southern Association play. Papai was awarded league all-star honors, and was runner-up for league MVP. Memphis made it to the playoffs but lost out in the finals.

He turned 40 in 1957, pitching in 29 games for Indianapolis (17 starts), but recorded a 5.56 earned run average and was 5-12.

Just before the season had begun, Al Papai married Ellen Claire Harrison on April 6, 1957. The Papais had no children.

His final season in baseball was a brief one, appearing in just five 1958 games for the Corpus Christi Giants, without a decision.

After baseball, Papai returned to government service, this time working for 20 years as a mail carrier for the United States Post Office at Springfield, Illinois. He was inducted into the Springfield Sports Hall of Fame.

After a long illness, he died on September 7, 1995, at St. John’s Hospice in Springfield. His wife survived him, as did two sisters and three brothers.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Papai’s player file and player questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, and the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 Mike Vickers, “Papai Aims To Be Starter,” Boston Herald, January 22, 1950: 83.

2 “Papai Saved From Mines By Baseball,” Christian Science Monitor, March 30, 1950: 16.

3 Handwritten note by Al Papai, in his player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

4 “B-R-S Honoree Al Papai Died Sept. 7,” The Bull Pen, Vol. 5, No. 9, September 1995. The above-noted1950 article from the Monitor, most likely written by Ed Rumill, said Papai had received three Purple Hearts.

5 “Five Newport News Players on Managers’ All-Piedmont Team,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, September 1, 1946: 17.

6 Johnny Lyons, “Light-Biffing Buffs Finish First on Hurling, Hustle,” The Sporting News, September 17, 1947: 27. Beers led the league with 25 wins.

7 Associated Press, “Pitcher Papai Lost to Buffs Through Ruling by Chandler,” Dallas Morning News, April 17, 1949: 1.

8 Harry Mitauer, “Papai Winning for Browns, Can’t Explain Why Cardinals Passed on Him as Starter,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, May 20, 1949.

9 United Press, “Browns Place All Players Over 28 on Trading Block,” Boston Globe, October 28, 1949: 29.

10 Mike Vickers.

11 “Papai Saved From Mines By Baseball.”

12 Earl Johnson, Charley Schanz, and Jim Suchecki were the others. See John Drohan, “Sox Shakeup Aimed at Complacency,” Boston Traveler, July 6, 1950: 17.

13 Dry, “The Dope Bucket,” Daily Illinois State Journal (Springfield), February 12, 1954: 13.

14 Associated Press, “Indians Buy Papai,” Morning Star (Rockford, Illinois), May 6, 1954: 21.

Full Name

Alfred Thomas Papai

Born

May 7, 1917 at Divernon, IL (USA)

Died

September 7, 1995 at Springfield, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.