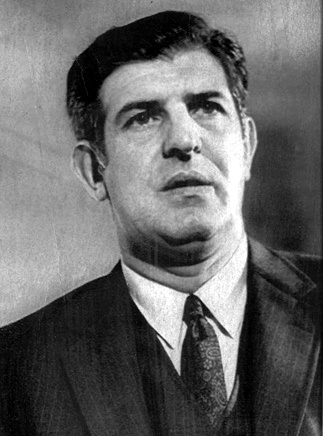

Al Salerno

An American League umpire for seven years in the 1960s, Al Salerno’s abrupt 1968 dismissal set off a legal firestorm and led to decades of personal struggles. In fact, Salerno never got over what happened to him, and to the very end of his life he remained angry and bitter over the game he had once loved.

An American League umpire for seven years in the 1960s, Al Salerno’s abrupt 1968 dismissal set off a legal firestorm and led to decades of personal struggles. In fact, Salerno never got over what happened to him, and to the very end of his life he remained angry and bitter over the game he had once loved.

Alexander Joseph Salerno was born to Nicholas Salerno and the former Anna Siciliano on March 19, 1931 in Utica, New York, about fifty miles east of Syracuse. He was one of three children in the family, joined by Marguerite and Michael.i Although known as Al during his professional umpiring career, in his lifelong home of Utica, he would always be “Bobey.” Salerno was always a big and active kid, and it was no surprise that he became an accomplished athlete, becoming a pitching star in Utica. In 1949, he finished 31-1 pitching for Proctor High and his American Legion team, while also pitching for a semi-professional club.

Salerno signed with the Boston Red Sox in 1949, and pitched the next season for Marion in the Ohio-Indiana League. He did not pitch very well (3-4, with a 6.29 ERA in 83 innings), but he was 19 and had some time to learn the fine art of professional pitching. The next year he was property of the Kinston (North Carolina) Eagles of the Coastal Plan League, but he apparently did not pitch, likely due to injuries. He spent the next two years in the US Army, serving part of his hitch in Korea. While overseas he was thrown out of the back of a jeep he was riding in, landing on his pitching shoulder. After his discharge in the fall of 1953 the Red Sox released him and the next spring he went to spring training with Olean (New York), a New York Giants affiliate in the PONY League. His shoulder had not recovered, however, and after Olean released him in late March he returned to Utica to start over.

He worked a number of short-term jobs before joining the New York State police force. During his service, he spent time as both a trooper and a motor vehicle licensing examiner based out of Troy. In the meantime he began umpiring local softball and baseball games. His interest kindled, in the winter of 1957 he enrolled in Al Somers Umpire School in Daytona Beach “It started out to be more of a vacation trip,” Salerno recalled.ii Instead, Salerno graduated at the top of his class, and decided to become a professional umpire.

He began his career in the Pioneer League in 1957, but quickly advanced to the Eastern League in 1959, then to the Pacific Coast League in 1960. After just two years in Triple-A he joined the American League staff in September 1961. His rapid rise and his relative youth (just 30 years old) testify to the high regard officials had for his umpiring ability. With just 20 umpires on the staff and jobs hard to come by, Salerno could look ahead to perhaps 25 years of major league umpiring.

The six-foot-three, 210-pound Salerno umpired six games at the tail end of the season, and on October 1 he was stationed at third base when Roger Maris hit his record-breaking 61st home run in Yankee Stadium.

Salerno had married the former Joan Marie Nole in 1959, and they soon welcomed a son, Nicholas. Joan remained an English teacher in Utica. Like most umpires, Salerno had to endure being away from his family for long stretches of the season. Unlike the players, they did not spend half of the season in one place—they were “on the road” from March through September. “There have been times,” he said in 1966, “when I’ve been away from home for as many as 60 days. So you live by the phone and that is rather expensive.”iii Salerno’s highest salary was $12,000, so one had to love the profession to endure the lifestyle.

Within a few years he had settled in to his job, like most good umpires keeping his name out of the papers. In due course he was selected to umpire (in right field) for the 1964 All-Star Game, and a World Series was likely to come soon. He had a notable run-in with Orioles manager Hank Bauer in 1964, which resulted in fines for Bauer and his pitcher Steve Barber. But his reputation remained very solid in the profession.

Salerno’s life changed on the morning of September 16, 1968. He was lying awake in a hotel room in Cleveland, having umpired the Indians game the day before. He received a call from American League president Joe Cronin, the boss of the umpiring staff. Cronin told Salerno that he, along with crewmate Bill Valentine were fired effective immediately. They were bad umpires, Cronin told them, and he soon told the press the same thing.

Another story soon emerged. It turned out that Salerno and Valentine had been working behind the scenes to organize the AL umpires. The NL staff had formed a union a few years earlier, and the two arbiters were trying to get their colleagues to join up to form a single union of major league umpires. The NL officials made considerably more money and received greater benefits than their AL counterparts, a case Salerno and Valentine were slowly making with their cohorts. Salerno had attended a meeting just three days earlier in Chicago and had sent notes to his fellow umpires reporting what he had heard.

Most of the press rallied to the umpires’ cause, as no one really believed Cronin’s explanation for the dismissals. Both umpires had received regular raises and good performance reviews. Salerno had received an unscheduled bonus just one year earlier. The two were assigned to same crew, an unlikely pairing if they were truly incompetent umpires. Many AL managers, some of whom had had on-field squabbles with the umpires, came to their defense.

After the season, the remaining AL umpires joined up with their NL counterparts to form the Major League Umpires Association, just as Salerno had wanted. In January 1969 the union filed an unfair-labor-practice claim with the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), and later that year the Salerno and Valentine filed a $4 million lawsuit in federal court against Major League Baseball and the American League, alleging defamation of character and federal antitrust violations.

Before the NRLB hearing in June 1970, the American League tried to reach a settlement with the two umpires. Valentine wanted to settle, but Salerno’s lawyer convinced him that he could win a big settlement. At one point the AL offered them full reinstatement, back pay, and $20,000 in salary (thanks to the union, the new going rate for their service level). In what was seen as a face saving gesture by Cronin, the umps would have to spend time in the minors in order to “improve” their skills. Valentine got in his car and drove from Little Rock to Utica to try to convince Salerno to take the deal. Salerno wouldn’t budge, and the league wouldn’t settle without both umpires agreeing.

The umpires ultimately lost both cases, mainly because they were unable to prove that Cronin knew that they were organizing. Neither man ever umpired again.

Still just 37 years old when he was fired, Salerno returned to Utica bitter and broken by his fate. “I gave baseball everything I had,” he said a few years later. But there were no more good feelings. “If every baseball stadium in the country blew up tomorrow, I’d be happy.” He blamed baseball management, but he later came to blame the umpires for not standing up for him. The union (which Salerno had helped bring about) had improved the standing of the umpires considerably, but why wouldn’t it help him? He had not worked long enough to draw a pension—the service rules had been lowered, but did not apply to the pre-union umpires.iv

When I first spoke with Salerno in June 2007, nearly 39 years after the firings, the old umpire’s mood had not improved. “I served my country, and my country screwed me over,” he said. He hadn’t held a steady job in the ensuing years, mainly due to health problems. He’d suffered a back injury during his umpiring days, but in the years since had suffered a heart attack and several other medical setbacks. His wife left him in the 1980s (“She got sick of my complaining,” he said), though they remained good friends. Their son Nick remained close to both parents.v

He had not stopped fighting the case. He wrote to lawyers, judges, the commissioner’s office, and the umpires union (the original union had decertified and a new one had taken its place) regularly over the years. When we spoke he had just written to John Roberts, the newly minted Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. He wanted to know what I was going to write because he thought I might be able help his case. He was 76 and had long given up the dream of working a game, but he had medical and financial problems that a pension could have helped.

In contrast, Bill Valentine, who had badly wanted to take the settlement offer and umpire again, returned to Little Rock and became the general manager for the Arkansas Travelers, living a better and happier life than the one that had been taken from him.vi Salerno, when asked about the proposed settlement in 2007, was adamant that baseball management would have kept them in the minors and never reinstated them. Most observers, and Valentine, believed otherwise.

Al Salerno died on August 5, 2007 at the age of 76. He was survived by his son Nicholas, who lived with his own family in Sarasota, Florida.

i “Bobey Salerno 1931-2007,” from TheDeadballEra.com, reprinted from FiskFuneralhome.com, dated August 6, 2007.

ii Bill Hengen, “Policeman Behind the Plate,” Baseball Digest, October 1966, 87-88.

iii Hengen, “Policeman Behind the Plate”.

iv Peter Pascarelli, “Salerno, Former Major League Umpire, Is a Beaten, Bitter Man,” Utica Daily Press, June 16, 1976, 22.

v Al Salerno, interviews with author, June-July 2007.

vi Bill Valentine, interview with author, June 2007.

Full Name

Alexander Joseph Salerno

Born

March 19, 1931 at Utica, NY (US)

Died

August 5, 2007 at Utica, NY (US)

Stats

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.