Al Schacht

To say that Alexander Schacht was obsessed with baseball is to understate. He was possessed by it. Schacht was an undersized man with an oversized heart and love of baseball. It consumed him as he traveled from hamlet to hamlet trying to sell his wares as a pitcher. When he did finally make it to the big leagues, he hurt his arm and his playing days were over. But Schacht had something more than pitching ability. He had the talent to make people laugh. He did not have to speak a word; his actions portrayed what he was trying to convey. What he conveyed so pointedly is that there is a jester to put things in perspective. The jester points out that life is often absurd, so instead of letting it get us down, we should laugh at the absurdity in baseball or life. Schacht was the court jester, crying and laughing at the world of baseball and life.

To say that Alexander Schacht was obsessed with baseball is to understate. He was possessed by it. Schacht was an undersized man with an oversized heart and love of baseball. It consumed him as he traveled from hamlet to hamlet trying to sell his wares as a pitcher. When he did finally make it to the big leagues, he hurt his arm and his playing days were over. But Schacht had something more than pitching ability. He had the talent to make people laugh. He did not have to speak a word; his actions portrayed what he was trying to convey. What he conveyed so pointedly is that there is a jester to put things in perspective. The jester points out that life is often absurd, so instead of letting it get us down, we should laugh at the absurdity in baseball or life. Schacht was the court jester, crying and laughing at the world of baseball and life.

He would come in with his battered top hat and ragged tails, blowing mightily on a tuba. Maybe he’d wield a catcher’s mitt that weighed twenty-five pounds into which one could fit an entire meal. In fact, this zany guy once ate a meal off home plate. Zany like the Ritz or Marx brothers, Schacht became the first Clown Prince of Baseball. Alexander Schacht or just plain Al was a smart buffoon. One wonders when clowns perform whether they are really happy or sad or both. Tragedy and comedy hang side by side in many theaters, and just a turn of the mouth can be sad or happy.

Al Schacht once said, “I came into this world very homely and haven’t changed a bit since.” Schacht was born November 11, 1892, in the Bronx on the site that would eventually become Yankee Stadium. Samuel Schacht, his father, was born in Russia in 1863, the son of a prominent farmer. Samuel was a skilled locksmith and an ironworker, once making a set of iron doors for the White House during the Teddy Roosevelt administration. Al’s mother, Ida, also born in Russia, came from an aristocratic family. Her father was the town rabbi, and his word was final in all disputations. Samuel and Ida married in 1887. The military wanted Samuel for his locksmith skills, but Samuel and Ida tried to escape. They were caught at the border, and Samuel was imprisoned in Russia. However, with some exchanges of money Samuel was freed, and they continued on to London, staying for fourteen months until Samuel received enough money from his brothers in the United States to book passage for Ida and himself to get to America.

Al was born on Catharine Street. He had an older brother, Louis, who became a designer, a sister named Esther, and twin brothers Mike and Herman. Herman died as an infant. Al was a sickly child requiring numerous visits to the clinic. He had cramps and stomach pains continuously. Ida was tiny, but she ruled the roost. His father was a soft-spoken man who encouraged Schacht to pursue whatever he wanted in life and not go around asking people if he should do this or that. Wanting him to become a rabbi, Al’s mother was unhappy about his decision to become a professional baseball player. Older brother Louis was a good student, and Ida was always asking Al why he couldn’t be like Louis.

Schacht had a hard time adapting to school. His mind was always on baseball. And to make matters worse he had to fight his way to and from school every day with the Irish and Italians. When Al entered Commerce High School in 1908, he tried out as a pitcher for the team. But the coach took one look at him and asked how much he weighed. Schacht replied 125. The coach decided he was not big enough to pitch and put him at second base. It was a disaster; by his own account he could not hit, field, or run. In Schacht’s mind he was a pitcher, and he persuaded the coach to keep him on the squad as an extra pitcher. Al took a job as a delivery boy for Cohen and Rosenberger, a jewelry store, and played semi-pro ball for various teams on Sundays. He was out of school until 1910 when he returned to Commerce High. He now felt he finally had a good chance to pitch for the team, as the star pitcher had departed the school. Indeed, he made the team, and he and the team went undefeated for the season, even beating some college teams. At the end of the season Commerce High was to play Stuyvesant High for the championship of the city. On Friday before the game the entire Commerce team along with the coach and catcher of the Stuyvesant team were called to appear before the Board of Education. Al thought they were going to honor them because of their successful season. It turned out the members of the board accused them of playing semi-professional baseball and forbade them to play any more sports at their respective schools. Al dropped out of school for good.

Abe Goldberg, a public school principal, approached Al one day and asked if he would like to play semi-pro baseball for Walton, New York. He offered Al four dollars a week and board. Al agreed. He was nervous about telling his parents. But they assented, and Al went to Walton. He was greatly surprised by his mother’s acquiecence to the idea, but then Al had already made some money in his previous semi-pro time and had given every penny to his mother.

The Walton Rifraffs played in a league composed of small towns like Oneonta, Stamford, Norwich, Liberty, Norris, Roscoe, Sidney, Delhi and others. When Schacht reported to Walton, thirty-five owners of the team, primarily shopkeepers, were sitting in the stands. They took a look at Schacht and said he was too small. They also had another pitcher they all wanted instead of Al. But Abe Goldberg prevailed, and Schacht went on to win thirteen consecutive games for Walton. Whenever a pitcher won a game for Walton, it was the custom to give him a three-dollar meal ticket and a free ice cream soda at Evans Dining Car and McLean’s drugstore. Schacht never got any of them until he had won his thirteenth game.

It was at Walton that Schacht first tried clowning. Before certain games the Walton team would host social events, and Al started to clown around. He would impersonate a famous actor, then a pitcher who was getting hit all over the place and refusing to go to the shower when the manager came out to lift him. The fans loved it, and Schacht continued his pantomime act every time they had a social event.

When the Walton team was about to play the Cuban Stars, a Negro league team touring the United States, Schacht was scheduled to start the game and heard that Cincinnati scout Mike Kehoe would attend the game. Concerned that his small stature would not make a good impression on the scout, he put on extra socks, two sweatshirts, sliding pads, anything that would make him look as if he weighed at least 150 pounds, instead of 132. It was brutally hot day, and with the extra equipment on he struggled mightily and managed to pitch a good game even though he lost to the Cuban star pitcher Jose Mendez, 2-0.

Kehoe never said a word to Al, who was downcast for a couple of weeks when suddenly he got a wire from Clark Griffith, the manager of the Cincinnati team, to report to the team at the Washington Park in Brooklyn as soon as possible. Elated, he got there in record time and introduced himself to Griffith. Griffith asked where his big brother was. Al was insistent, and Griffith said Kehoe told him he weighed 160 pounds. Al fired back that he hadn’t had lunch yet and had just pitched the day before but would put the weight back on. The weight problem constantly plagued Schacht in his quest to play major league baseball. Moreover, he still suffered stomach pain, which was finally diagnosed as an ulcer. Griffith wanted to farm Al out to Fort Wayne, Indiana, but Schacht said he could make more money playing semi-pro ball, turned Griffith down, and went back home.

Love came into Al’s life at this point-Esther Levine, a beautiful dark-haired girl. He saw Esther almost every night. One day still pitching for Walton, he saw Billy Gilbert, manager of the Erie Club in the Class C Ohio-Pennsylvania League. Gilbert asked Schacht if he would like to try out for the Erie team. Figuring it was a step up from Walton, Schacht said yes on the spot. He reported to the Erie club but spent most of his time on the bench. Gilbert was still concerned about Al’s weight, afraid to take a chance on him. Gilbert gave up on Schacht and handed him his release. Al sat in the lobby of the hotel wondering what his next move should be, when Gilbert showed up to tell him he had recommended him to Jack O’Connor, manager of the Cleveland team in the outlaw United States League. The old weight bugaboo struck again. But Schacht insisted he could pitch well, and O’Connor liked his guts and took him on.

Schacht did not let O’Connor down. Called into relief his first time on the mound for the club, he worked five innings and struck out 11 of the 15 batters he faced to get the win. Schacht won five straight games for the Cleveland club, but the league folded at the end of the season.

Al was still seeing Esther, whose family wondered what his intentions were and asked him to come to their home. Esther’s family was not happy that he was a ballplayer. And Al, though he loved Esther, had no intention of getting married at this time because it would mean getting an 8-to-5 job and giving up baseball. When the Levines put pressure on Al, he decided to end the relationship and did not marry her.

Out of baseball Schacht got involved in the boxing business. He would go to the gym during the winter to keep in shape and do some boxing. A cousin of his from Boston wrote to Al and said he had a good-looking prospect and hoped Al would agree to manage him. So Al took on Joe White, an up-and-coming fighter. Joe was a good fighter, and after he had won several fights under Al’s tutelage, he was matched against Mike Gibbons. Al was unaware that White had now attached himself to some shady characters. As he walked down the aisle towards the ring with his fighter he suddenly felt a hard object pressed against his back. A voice said, “Take one more step and you’re a dead pigeon.” Al wasted no time getting out of the arena. That was the end of his ring management.

Tragedy struck Al when his beloved father contracted pneumonia and died. At the same time he received a notice to report for a tryout with Newark of the International League. Al felt good about this because the International League was one step away from the majors. He reported to the Newark Club, which left by boat for spring training in Savannah. Al still grieved for his father, however, and Harry Smith pulled him aside one day and told him he had the same thing happen to him when he was Al’s age. Smith told him to snap out of it and concentrate on baseball. Al felt good about Smith’s being concerned about him and responded well.

Al made the team and helped them win a pennant in the International League. The following year, 1914, the Federal League came into existence and offered Schacht a contract for $500 a month and a three-thousand-dollar bonus. Al thought it over and decided to go to the St. Louis of the Federal League. However, the next morning he received a telegram from Ed Barrow of the Newark team: “DO NOT JUMP. SPECIAL DELIVERY LETTER FOLLOWS.” Ed Barrow personally promised Al that he would see to it that Al was sold to a major league team. Al unpacked and worked very hard. The deal never came off. Barrow reneged on his promise. Al was enraged, for many of the players who’d jumped were welcomed back to the majors after the Federal League folded. He went to Barrow’s office, told him off, and stormed out.

Still the baseball bug ate away at him. He needed to play. So he signed with Newark again. The furies struck again, as he had his first sore arm. He could not pitch at all. Called into the front office, he was told that they were sorry about his sore arm but that he was suspended without pay.

World War I had been going on for over three years. The United States became involved in 1917, and Schacht was called up for induction. Al thought his hearing deficiency would exempt him, but he was passed and entered the Army. He stayed in the States playing baseball.

Discharged when the war ended, Al went to Newark to get his job back as a pitcher. They told him they were no longer interested in him. Schacht then signed with the Jersey City Giants. His arm was no longer sore, and he pitched solidly for Jersey City. Still, he ached to get to the big leagues. Schacht picked up The Sporting News one day and read that Clark Griffith, now manager and vice-president of the Washington Senators, was in need of pitchers. Al got an idea and started sending clippings when he won along with a letter praising Al Schacht and imploring Griffith to sign him up for the Senators. The letter was signed “Just a Fan.” After so many of these letters and clippings Griffith finally caved in and scouted Schacht himself. Schacht with Griffith looking on shut out Binghamton 2-0. A few days later Schacht received a telegram telling him to report to the Washington club and be ready to pitch. The Promised Land was now his. The roadblocks and disappointments all faded away as he triumphantly entered the hallowed grounds of big league baseball. Schacht arrived in Washington on September 20, 1919. The Washington Star had a headline that read “Al ‘Rip Van Winkle’ Schacht Joins Washington Club.” Schacht felt as if he had wandered in the desert for forty years before he reached his goal.

Schacht pitched and won two games at the tail end of the 1919 season. Instead of going home, he decided to go to Walton, Massachusetts, to rest, take long walks, and eat three meals a day. Still he did not gain much weight and tipped the scales at 138. In 1920 at Tampa for spring training with the Senators he met Nick Altrock. They soon formed a clown partnership. Al said that from the beginning he and Nick didn’t like each other and later in their partnership never spoke to each other. At that time Altrock was considered the number one clown in baseball. But Altrock was jealous and actually spied on Schacht. According to Schacht, one time Altrock saw him in the hotel and insisted they go drinking. When Schacht refused, Altrock called him a “Jew kike bastard,” cementing Schacht’s intense dislike of Altrock.

Al was doing fairly well as a pitcher with a 5-2 record at the end of June in 1920 and felt he really belonged in the majors. The day after Schacht absorbed a loss in Boston, Walter Johnson pitched a no-hitter. But it was a costly one because Johnson hurt his arm. The club had returned from Boston, and fans jammed the ballpark to root for Johnson, who could not pitch that day. Griffith was in a panic and asked for volunteers. Schacht raised his hand and said he’d do it. Griffith told Schacht, “If you win this game today, Al, as long as I have anything to say about this ball club you have a job with me. I mean it. I don’t care if you never win another game this season-you’ve got to win this one.”

Al was doing fairly well as a pitcher with a 5-2 record at the end of June in 1920 and felt he really belonged in the majors. The day after Schacht absorbed a loss in Boston, Walter Johnson pitched a no-hitter. But it was a costly one because Johnson hurt his arm. The club had returned from Boston, and fans jammed the ballpark to root for Johnson, who could not pitch that day. Griffith was in a panic and asked for volunteers. Schacht raised his hand and said he’d do it. Griffith told Schacht, “If you win this game today, Al, as long as I have anything to say about this ball club you have a job with me. I mean it. I don’t care if you never win another game this season-you’ve got to win this one.”

When the announcer at the center of the diamond announced that Schacht was pitching, catcalls, soda bottles, and seat cushions rained down on Schacht. But he stayed the course and beat the Yankees, 4-1. Schacht did not win another game that season. In a relief stint he got on base, and the next batter tried to sacrifice Schacht to second base. As Schacht slid into the bag, shortstop Donie Bush of the Tigers jumped up to snare a high throw and when he came down crashed heavily into Schacht. Al’s right shoulder absorbed most of the crash, and his pitching days were practically over.

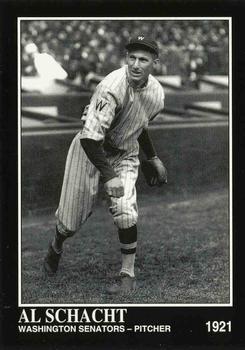

Schacht and Johnson, both suffering from a bad arm, were sent to various doctors, none of whom helped. Sitting alone in a hotel lobby, Schacht wondered what he’d do if he couldn’t pitch again. Suddenly he remembered that Griffith had said he would always have a job with him. Griffith made him a temporary coach. Al managed to pitch some in 1921, but the arm was not coming around, and he finally gave up on pitching. Schacht’s total major league statistics are 14 wins and 10 losses with a 4.48 earned run average.

Schacht roomed with Altrock. Al did not like it, but it was club policy that coaches room together. Though they disliked each other, they both felt that they could put together a comedy act and lengthen their days in baseball. The act really got going in 1922 World Series between the Giants and Yankees. Schacht and Altrock took their act to Colonel Jacob Ruppert, who approved, but Miller Huggins grumpily refused. However, John McGraw saved the day, hiring Altrock and Schacht to do their act. Al got a bonus when Griffith made him the third base coach of the Senators. Now he was getting paid for being a clown and a coach. Al was no clown as a third base coach; he was both serious and capable.

In 1928, Schacht became desperately ill. His weight dropped to 126, sharp pains gnawed at his stomach, and he had a bad case of dysentery. Schacht went to several doctors, who were puzzled by his illness. Finally he went to a Dr. Norman, who found the problem-bleeding ulcers. The doctor, seeing that Schacht was about to have an internal hemorrhage, irrigated them immediately. After the irrigation Schacht went to a sanitarium in Washington, where he followed the doctor’s orders, a special diet that resulted in the curing of his ulcers.

Schacht managed the Senators for a month in 1934. Player-manager Joe Cronin had broken his wrist and just gotten married, to Griffith’s adopted daughter Mildred Robertson. Griffith gave Cronin the rest of the year off and told Joe to go on a long honeymoon. The Senator team was in poor shape with mounting injuries and finished seventh. Schacht’s short managing career ended. Schacht never desired to be a manager and was glad it was over. After the 1934 season Schacht and Joe Cronin were traded to the Red Sox. That was the end of the partnership between Schacht and Altrock.

Now that Schacht and Altrock had split for good, Al was on his own as a clown and became the Clown Prince of Baseball. He entertained at World Series games, at All-Star games, and at every park in the majors.

When the United States was drawn into World War II in 1941, Schacht was asked to entertain the troops. He happily agreed to do so. In 1943 he went to North Africa. Schacht sensed that the biggest problem with the GIs was homesickness and that baseball stories would help them over the hump. His acts were a howling success wherever he went. Schacht was under enemy fire many times during his tours, tours that included Africa, Sicily, New Guinea, the Dutch East Indies and the Southwest Pacific. In a period of two months he played 159 stage shows, visited 72 hospitals and 230 wards, and traveled over 40,000 miles. He later went to Japan and the Philippines to do his shtick.

Schacht was given the Bill Slocum Memorial Award in 1946. The award was created in 1929 honoring a person who made the highest contribution to baseball over a long period of time. His comedic act both for baseball fans and GIs brought him a well-deserved reward.

The war over, Schacht gave up touring with his comedic act and opened a restaurant in New York. The spot was a famous place for sports figures, and Al would get up on stage from time to time and do his act. Love came into his life once again. He met Mabelle Russell, a vocalist at a local club, and they married. Schacht felt his life was complete. He had his soul mate and a fine restaurant that did well. There were also his old baseball buddies who showed up from time to time at his restaurant and his mother, who was now proud of him.

The court jester who through his life’s travails had conquered his own fears and helped others also see the absurdities of life was now a respected and successful restauranteur. He had faced death both in his personal illness and on the battlefield while entertaining troops. He fought his way into the major leagues only to suffer an injury that ended his playing career. But his sense of humor and of the absurd led him into the real essence of who he was. Upon first meeting him, one was struck by his loud in-your-face demeanor, but further study revealed a kind-hearted man. His laughing in the face of the absurdities of life brought him safely through tough times and helped people take their minds off the pressures of life if only for a few moments. Even though we suffer loss and failure, we can only lean back sometimes and laugh at all the craziness of life. Al did not solve problems as his rabbi grandfather did. Instead, he reached people through the medium of the human comedy.

Alexander Schacht died on July 14, 1984, in Waterbury Connecticut. He was 92 years old and was survived by Mabelle.

Al Schacht, left, known as the “Clown Prince of Baseball,” and Nick Altrock perform a comic routine before Game 1 of the 1924 World Series on October 4, 1924, at Griffith Stadium in Washington, DC. (LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

Sources

Al Schacht File at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in Cooperstown, New York.

Aronson, Harryette Schacht (cousin of subject). Interview with author.

Horvitz, Peter S., and Joachim Horvitz. The Big Book of Jewish Baseball. New York: S.P.I Books, 2001.

Levine, Peter. From Ellis Island to Ebbets Field. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992.

Light, Jonathan Fraser. The Cultural Encyclopedia of Baseball. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 1998.

Ribalow, Harry U. The Jew in American Sports. New York: Bloch Publishing Company, 1948.

Schacht, Al. G.I. Had Fun. New York: Putnam, 1945.

_____. My Own Particular Screwball. Garden City, New York: Doubleday, 1955.

Full Name

Alexander Schacht

Born

November 11, 1892 at New York, NY (USA)

Died

July 14, 1984 at Waterbury, CT (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.