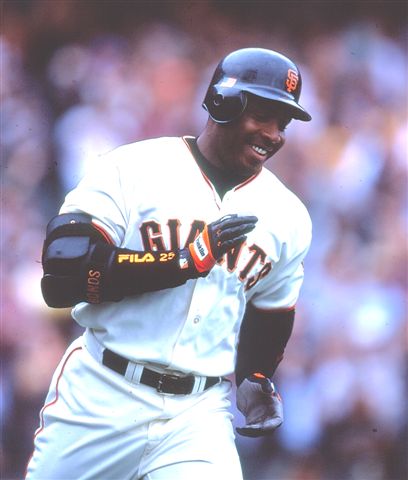

Barry Bonds

“For what shall it profit a man, if he shall gain the whole world, and lose his own soul?” The Bible may not have been referring to anything as crass as a baseball career, but this one sentence serves to describe Barry Bonds very well. A stellar career, rich, famous, holding many records, but his own actions and words have left him a pariah in baseball, perhaps never to attain the Hall of Fame status that he craved and that his career numbers suggest he would deserve.

“For what shall it profit a man, if he shall gain the whole world, and lose his own soul?” The Bible may not have been referring to anything as crass as a baseball career, but this one sentence serves to describe Barry Bonds very well. A stellar career, rich, famous, holding many records, but his own actions and words have left him a pariah in baseball, perhaps never to attain the Hall of Fame status that he craved and that his career numbers suggest he would deserve.

Barry Lamar Bonds was born on July 24, 1964, in Riverside, California, to Bobby Bonds and Patricia Howard. The teenagers had grown up next door to each other, Bobby the star athlete and Pat the beauty, and married at 17. Bobby came from a very successful sporting family; his sister, Rosie, competed in the 1964 Olympics as a hurdler, and his brother, Robert, was drafted by both the National Football League and the American Football League before their merger. A year after Bobby and Pat’s wedding, Barry was born, and two weeks after that Bobby signed a professional contract with the San Francisco Giants. He went on to a prolific major-league career, showing both power and speed while playing for eight teams in a 14-year career.

While Bobby was in the minor leagues, Barry lived with his mother in Riverside, where they welcomed a second son, Ricky, a year after Barry, and a few years later a third boy, Bobby Jr. The family also adopted a girl, Cheryl. The children were raised by the metaphorical village, their mother being helped by friends and family around town while Bobby was away playing baseball.

In 1968 Bobby was called up to the major leagues, making his debut with the Giants in June. He quickly established himself, and soon his family came visiting, Barry making his first appearance in a major-league locker room. Bobby and teammate Willie Mays had become close, and Bobby asked Mays to be Barry’s godfather.

In 1969 Bobby moved his family to San Francisco, to the almost exclusively white area of San Carlos. Barry was usually one of few black children where he lived and at the schools he attended. Later in life he referred to himself as having come from Los Angeles, in an attempt to gain some credibility, but black players who had grown up in the inner city would ridicule him for it.

In school Barry was an average student, but his athletic ability dominated people’s perception of him. Some people considered him a bully on the sports fields, although one of his teachers said that wasn’t the case, but rather that “whatever he was playing – Four Squares or dodgeball – he played to win.”1

Bobby was traded to the New York Yankees at the end of the 1974 season, just as Barry was beginning his own baseball career. As a 10-year-old, Barry awed the adults in the San Carlos Little League, where he played for the Lions Club Yankees under coach Lloyd Skjerdal. “It was as if he had appeared out of nowhere – just showed up one day, ready to be a star,” said Skjerdal.2 Barry hit over .400 each season in Little League, showing both the talent and cockiness that would follow him throughout his career.

In 1978 Barry entered Junipero Serra High School, which was well known for its athletic program, producing a number of future MLB and NFL stars, like Jim Fregosi and Tom Brady. Barry’s high-school coach, Tim Walsh, said, “He wanted to be great. A lot of kids just wanted to play. That wasn’t enough for him.”3 Bonds played basketball and football in high school for a couple of seasons, and played well in both, but it was clear that baseball was his preferred sport. He led the league in home runs, and in his senior year he hit .467 with14 homers and 42 RBIs. But he never studied, he was late for practice, and showed up other teams on the field (watching his home runs, for example, something he would continue to do in the major leagues). As scouts came sniffing around, this behavior began damaging his reputation, with scouts noting his arrogance, one even writing “Asshole” under “Attitude/Personality” in his report.4

Bobby had retired from professional baseball, his career derailed by alcoholism, which had turned a number of teams away. Thus the news that he would act as Barry’s adviser in the coming 1982 draft caused Barry’s stock to drop. An expected first-rounder, he fell to the Giants in the second round. They offered Barry $70,000 to sign, but when Bobby said he wanted $5,000 more, the Giants said no thanks, and Barry headed to college.

Barry attended Arizona State, one of the powerhouses of college baseball. A starter as a freshman, he led the team with 11 home runs and 54 RBIs, and dominated the College World Series, though the team finished third. Barry didn’t make friends easily; his college coach, Jim Brock, said: “I don’t think he ever figured out what to do to get people to like him.”5 Bonds in fact made enemies with his attitude, skipping or being late for practice, ignoring team rules, and generally acting as the big man on campus. Brock, trying to settle things in 1984, told the team to vote on whether Bonds should stay on the team. Almost all the players voted against Bonds, which surprised Brock since he had expected them to want to keep his playing ability. Switching his plan, he told them that he wouldn’t remove Bonds since their vote had not been unanimous.6 The team went back to the College World Series, where it lost again, but Bonds set a College World Series record with hits in seven straight at-bats.

Bonds spent a short period in Alaska in the summer of 1983 after signing with the Alaska Goldpanners of Fairbanks. Because of school commitments, he never played a game in Alaska. He suited up but did not play in the Alaska Baseball League tournament, then played six games for the Goldpanners in the National Baseball Congress World Series in Wichita, Kansas, where he went 4-for-18 with no home runs.

In 1985 Arizona State suffered severe penalties for NCAA violations; some players were suspended and the team was banned from postseason play. While the team struggled, Bonds got even better, hitting .368-23-66 and being named a second-team All-American. He decided he would turn pro after his junior year. In June 1985 Bonds was drafted in the first round by the Pittsburgh Pirates, and he signed a couple of days later for a bonus of $150,000. The Pirates sent him to play for Prince William in the Class A Carolina League, where Bonds performed well, hitting .299 with 13 home runs. This earned him a promotion to the Triple-A Hawaii Islanders of the Pacific Coast League the next season. Bonds enjoyed his time in Hawaii, spending days on the beaches and nights in the ballpark, but he wasn’t there long, hitting .311 with 7 home runs in 44 games.

With the Pirates struggling at 17-24, Bonds was called up and made his major-league debut on May 30, 1986, against the Los Angeles Dodgers at Three Rivers Stadium. Looking to use his speed, manager Jim Leyland inserted Bonds into the leadoff spot, where he remained for the next four years. His debut was a day to forget for Bonds, as he went 0-for-5 with a walk and three strikeouts, and the Pirates lost in 11 innings. Bonds got his first hit the next day, leading off the first inning with a double off Rick Honeycutt – and was then immediately picked off second by Honeycutt.

In one of those scheduling oddities, Bonds ended up with a hit before his major-league debut. The Pirates and Cubs had played on April 20, but the game was suspended in the 14th inning with the score tied. The game was made up on August 11, and Bonds, now with the Pirates, pinch-hit in the 17th inning, hitting a single that scored two runs (one of them on an outfield error), which proved to be the difference in the score. Because major-league rules consider the date of a suspended game to be the date on which it began, Bonds is credited with a hit and an RBI on a date more than a month before his official debut on May 30.

It didn’t take Bonds long to show his power, his first major-league home run coming on June 4 in Atlanta off Craig McMurtry, a day that ended with four hits and four RBIs. It took a few more days to get a stolen base, when on June 7 Bonds stole twice against Dwight Gooden of the New York Mets.

Bonds ended the season hitting just .223 and striking out 102 times. But he showed flashes of his future self, with 16 home runs and 36 steals. This was enough for Bonds to finish sixth in the National League Rookie of the Year voting.

Bonds kept improving with the Pirates, and the team followed. Leading off and running wild, he continued to show the combination of power and speed that he had shown in his rookie year. In 1987 the team traded for Andy Van Slyke to play center field, pushing Bonds to left. This was an acknowledgment that Bonds had not been a good center fielder in his rookie season, seemingly ignoring coaching and playing shallow, trying not to show how weak his throwing arm was. The problem with that was that balls hit over his head could roll forever.

Van Slyke won his first Gold Glove after the 1988 season, and Bonds admired the trophy Van Slyke received. “Next year I’m gonna win me one of these,” he said. It actually took him two years, but in 1990 he began a streak of winning eight Gold Gloves in nine seasons. Van Slyke said that Bonds had felt he hadn’t needed to be a good outfielder, but once he decided to, “he willed himself to become great.”7

In June 1987 the Pirates traveled to Montreal for a series with the Expos, and Bonds went to a local strip club, where he met the bartender, Susann “Sun” Branco. After a telephone courtship for the rest of the season, Sun moved to Phoenix to live with Barry at the end of the year, and in February 1988 they were married in Las Vegas.

In June 1987 the Pirates traveled to Montreal for a series with the Expos, and Bonds went to a local strip club, where he met the bartender, Susann “Sun” Branco. After a telephone courtship for the rest of the season, Sun moved to Phoenix to live with Barry at the end of the year, and in February 1988 they were married in Las Vegas.

Leading off for the Pirates, Bonds got better and better each year. He was hitting for power, he was stealing regularly, and was showing all-round ability in everything he did. He wasn’t liked, though, the working-class city of Pittsburgh occasionally seeing him making little effort, while players like Van Slyke busted on every play. Bonds was almost traded a couple of times, the Pirates making it clear that if they got a good package they would make him available. But he stayed, eventually moving in 1990 to fifth in the batting order, behind Van Slyke and Bobby Bonilla, where the three would spearhead a powerful middle of the order and bring success to the Pirates. “He’s maturing as a player and he’s coming of age,” said Leyland.8

Bonds’ success gleaned personal rewards as well: his first of 14 All-Star games, and his first MVP award for a 1990 season in which he hit .301-33-114. “I decided this year was time for me to get the respect I deserved for myself,” he said.9 He finished a close second in the MVP race to Terry Pendleton of the Braves the next year, many speculating that Bonds’ personality and relationship with the media cost him enough votes for him to lose the race. He made sure that wouldn’t matter the following year, winning the MVP again in 1992 with another dominant season.

Bonds led the Pirates to three postseasons in a row in 1990-92. In those three playoff series Bonds hit just .191 in 20 games, with one home run, coming in a 13-4 win. In one of the iconic moments in postseason history, the Atlanta Braves beat the Pirates in the 1992 NLCS, the final play of the series being Francisco Cabrera’s hit to left field that scored Sid Bream with the winning run, Bonds’ throw home just too late.

In high school, in college, and in the major leagues, Bonds’ performance when the season was on the line was nowhere near his regular-season performance. This was because the opponents were much tougher, and because those teams, recognizing that Bonds was the biggest threat, generally pitched around him. His postseason mediocrity led Pirates fans to say good riddance when he left, using anything to mask their disappointment at their star player leaving.

As his time in Pittsburgh wore down, it became clear that the small-market Pirates would not be able to re-sign Bonds to the big contract the market could give him. He entered free agency as the premier player on the market, but found himself not as wanted as he thought he would be. His personality and his disdain for both fans and media led some teams to think he would be more trouble than he was worth. They were wrong, of course; it has been shown many times in history that performance on the field can far outweigh actions off it. But still, Bonds’ agent, Dennis Gilbert, had to call around and beg teams to make an offer. Their lukewarm response bothered Bonds, but his agent mentioned any kind of contact to the media, telling journalists how many teams were interested in his player. This ended up becoming somewhat of a joke within baseball circles.

Bonds’ demands to be the highest paid player in baseball were more than even the Yankees could afford. But there was a new owner in San Francisco, and as many new owners do, Peter Magowan wanted to make a splash. Splash he did, signing Bonds to what was then the biggest contract in baseball, for six years and $43 million. Bonds was returning to his childhood home. “Every time I step on that field … I know my godfather’s in center field and my dad’s in right field,” he said.10

Immediately Bonds alienated Giants fans, though, being given Mays’ retired uniform number 24. (He quickly changed to 25 when there was an outcry.) That alienation didn’t last long, as he won the fans over with his performance on the field.

For the rest of his career, even when it seemed as if the rest of the baseball world had turned against him, Bonds was loved in San Francisco. He was theirs and they were his, whether he returned their love or not.

Bonds started with a bang in San Francisco, leading the league with 46 home runs and 123 RBIs (his only RBI title) in 1993, and finishing fourth with a .336 batting average, establishing himself as a legitimate Triple Crown contender. He won his second MVP in a row. But then things changed. Bonds still performed at an outstanding level, but he had set the bar so high that when he didn’t reach those heights he lost MVP votes. For example, in 1995 he finished 12th in the voting, when WAR (wins above replacement) suggest that he was the second-best player in the league, behind Greg Maddux (who finished third in the MVP balloting). Unless he was having a truly dominant season, it seemed, voters were not giving him the benefit of the doubt. “Once you’ve won it a few times, the standards for you are very high,” he said11

In 1996 Bonds became just the second player to hit 40 home runs and steal 40 bases in a season. (Jose Canseco in 1988 had been the first.) Bonds accomplished the 30-30 feat five times, matching his father, Bobby, as the only two players to have five 30-30 seasons. On three other occasions Barry was close, each time having enough home runs but twice finishing with 29 steals and once with 28.

In 1993, Bonds’ first season in San Francisco, the team had made a huge leap, going from 72 wins to 103, but missing out on the playoffs as Atlanta won 104 games that year. The Giants spent the next few years struggling, but setting things up for a run from 1997 to 2004 in which they finished first or second in their division each year.

In 1998 Bonds got one of the ultimate honors: being intentionally walked with the bases loaded, just the fifth time that had ever happened in the major leagues, and the first since 1944. On May 28, with the Arizona Diamondbacks leading 8-6 with two outs in the ninth, Buck Showalter ordered Bonds walked. The next batter lined out to end the game. This was a huge sign of respect for Bonds, and intentionally walking him (albeit without the bases loaded) was a trend that would grow to historic proportions.

Bonds was a very private person, not letting many people into his inner circle even when he was a child. Stories abound about his social interaction, both with teammates and others. He reportedly did things in private for many people, not wanting any publicity about them. Other reports talk of him yelling at youngsters seeking his autograph. In the clubhouse he was disliked, a loner whom other people didn’t get on with at all. His attempts at humor often fell flat, tending to insult others, and when others played pranks on Bonds, he tended to take it as an insult.

Bonds would use the media when he needed to but would ignore them or be rude to them when he didn’t. He spent much of his career telling reporters “tomorrow” when they asked for an interview, but of course tomorrow never came. Much of this attitude came from his father’s career; Barry had seen how the media had treated Bobby when he fell into drinking and wasting his talent. Bobby had instilled the idea that the media would raise you up when they wanted to and tear you down when they were done with you, and Barry took it to heart. He regularly had people in the locker room protecting him from reporters trying to approach, and would often blow off prearranged meetings or interviews.

All these stories paint a picture of a lonely man, one with a desperate need to be loved and admired for his performance but unable to open up and let others in and see beyond the player. Bonds was admired for his feats, but never loved by fans around the league like his contemporaries, people like Ken Griffey Jr. and Sammy Sosa.

Bonds had divorced Sun in 1995, and married Liz Watson in 1998. They had known each other since before Barry married Sun, a friendship that Sun was not happy about. But Bonds had another life on the road, spending many road trips in the company of a girlfriend, Kimberley Bell. That affair would become public knowledge in 2005, causing Bonds much trouble both personally and in legal matters.

Bonds had a son, Nikolai, in 1990 and a daughter, Shikari, in 1991 with Sun. The children did not spend much time with him, living with their mother after they divorced. They would spend a couple of weeks during the summer with their father, but were never close. Bonds had another daughter, Aisha, in 1999 with Liz. He and Liz separated a couple of times, then divorced in 2010.

After the 1998 season things changed for Bonds. He had just watched Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa battle for the home-run record, and watched the baseball world’s attention turn to them and away from him. Bonds always wanted to be in the limelight. He changed himself and achieved a new level of greatness because of this. Some say it was a strong work ethic that brought him through. Many others allege he did it illegally, that this was the period when he began using performance-enhancing drugs (PEDs) to boost himself to new heights.

In the winter following the 1998 season, Bonds began working with a trainer called Greg Anderson. Anderson was a low-level steroids user and dealer, hanging out in local gyms. Bonds began exercising with him, lifting weights and working out in an intense fashion. Anderson also introduced him to various steroids, which Bonds took on a regular basis. He showed up in spring training in 1999 having put on a lot of muscle weight. On first seeing him, teammate Charlie Hayes said to a reporter “Did you see my man? … He was huge!”12 But the rapid muscle gain came at a cost; in early 1999 Bonds suffered a torn triceps from stressing his elbow so much. He required surgery and eventually missed a third of the season.13

Bonds set a career high for home runs in 2000, with 49, but that was just a warmup. The 2001 season began with an Opening Day home run, followed shortly by six straight games with home runs. On April 17 he joined the 500-home-run club with a blast into San Francisco Bay off Terry Adams of the Dodgers. In May he hit nine home runs in six games, including three in a game in Atlanta. After a slow July (six home runs) he ended the month with 45, not far off the pace to attack McGwire’s record 70. Bonds passed his own career high on August 11 with his 50th home run of the season, and kept on going.

He had 63 home runs on September 11, when events at the World Trade Center shocked the world and put baseball on hold. It could have been the end of Bonds’ chase for McGwire’s record if the ensuing games had been canceled, but instead they were postponed and baseball resumed a week later. Bonds resumed hitting home runs, and was up to 69 with a week left in the season, when the Giants went to Houston for a three-game series. The Astros were fighting for a playoff spot, and were determined to not let Bonds beat them. They pitched around him all series long, to the ire of their own fans, who had filled the park in expectation. It wasn’t until the ninth inning of the third game of the series, on October 4, with the Giants leading 9-2, that the Astros finally pitched to Bonds. Bonds homered off Wilfredo Rodriguez to tie McGwire for the single-season record. Back at home against the Dodgers the next day, Bonds took care of things quickly, homering in the first and third innings off Chan Ho Park to break the record, and adding another on the last day of the season to set the single-season record at 73.

Bonds was rewarded with the National League MVP for 2001, the first player to win four MVPs. He also signed a new contract with the Giants in January 2002, a five-year, $90 million deal that astounded people because he was 37 years old. With his age and related injuries – a painful degenerative disk in his back – no one expected that he would be playing by the end of the contract.

By now Bonds was feared, perhaps the most dangerous hitter of all time. He was being intentionally walked at all-time record rates, his 68 intentional walks in 2002 blitzing Willie McCovey’s record of 45 in a season. Two years later, in 2004, Bonds was intentionally walked an incredible 120 times, out of a total of 232 walks, which contributed to his reaching base 376 times that season, just three behind Babe Ruth’s record. Teams would rather put Bonds on base and take their chances with anyone else. The Giants reaped the reward, Bonds scoring over 100 runs for them every season from 1993 through 2004 except for strike-shortened 1994 and injury-shortened 1999. Because of all the walks, he usually ended up scoring more runs than he drove in, a factor in his winning just one RBI title, in 1993. Bonds would probably have broken the career RBI record if he hadn’t been walked so much (and spent the first four years of his career leading off). Still, his 1,996 RBIs were fourth all-time when he retired, not far behind Hank Aaron’s 2,297.

Bonds was well rewarded for his performances in the early 2000s. In 2000 he finished second in the MVP race to teammate Jeff Kent, who hit .334-33-125 compared with Bonds’ .306-49-106, and got 22 first-place votes to Bonds’ 6. It is reasonable to say that Kent benefited from hitting behind Bonds in the lineup, and by most advanced statistical measures Bonds was the better player (WAR of 7.7. against 7.2 for Kent).

Bonds was well rewarded for his performances in the early 2000s. In 2000 he finished second in the MVP race to teammate Jeff Kent, who hit .334-33-125 compared with Bonds’ .306-49-106, and got 22 first-place votes to Bonds’ 6. It is reasonable to say that Kent benefited from hitting behind Bonds in the lineup, and by most advanced statistical measures Bonds was the better player (WAR of 7.7. against 7.2 for Kent).

Bonds then was voted the MVP in four straight seasons, 2001-04. No other player ever won more than two in a row, and Bonds’ total of seven MVPs outstripped everyone else; the next highest total, shared by nine players, is three. Bonds was simply dominating the league. He won two batting titles, hitting .370 in 2002 and .362 in 2004. In 2001 he barely missed breaking Ruth’s single-season OPS record, then he broke it in 2002, and again in 2004.

There are hardly words to describe how dominant Bonds was in that period. Debates will always rage, but statistically Bonds’ efforts from 2000 to 2004 can be claimed as the greatest five-year period ever for a hitter.

But for all Bonds’ personal success, team success proved elusive. In the 15 seasons he played for the Giants, they won just three division titles (1997, 2000, 2003), losing the National League Division Series each time, and Bonds struggled in all three series. In 2002, their most successful postseason while Bonds was there, they finished second in the National League West, and with their wild-card entry into the playoffs, Bonds finally hit well in the postseason, as the Giants beat the Braves in the NLDS, then the Cardinals in the NLCS.

So Bonds got his one appearance in the World Series spotlight that year against the California Angels, and did all he could, having one of the greatest World Series of all time. In his first World Series at-bat he homered leading off the second inning of Game One, and the Giants held on to win 4-3. In Game Two he walked his first three at-bats, but Giants pitching couldn’t keep the Angels down, and even though Bonds hit a solo homer with two out in the top of the ninth to bring the score to 11-10, it merely staved off defeat when the next batter popped out to end the game.

Bonds put on another display of power in Game Three with a homer in the fifth inning, making it three straight games with a home run, but this time the Angels were far ahead and it didn’t make a difference. By now the Angels had awakened to the fact that Bonds was at last a postseason threat, and intentionally walked him three times in Game Four, although the rest of the Giants did enough to squeak out a 4-3 win. They pitched to Bonds again in Game Five (he hit two doubles), but only because the Giants ran away with the game, 16-4. The Series returned to Anaheim with the Giants leading three games to two, and again Bonds was worked around. He homered leading off the sixth in Game Six, but was walked twice and the Giants bullpen blew a 5-0 lead to lose 6-5. And in Game Seven Bonds was quiet, with a single and a walk, but so were the rest of the Giants and the Angels were 4-1 winners to clinch their first World Series title.

Bonds’ one shot at a ring was gone, despite having by far his best postseason ever. He had hit .471 in the World Series with four home runs (tied with several others for second all-time), 6 RBIs and 8 runs scored, with seven of his record 13 walks being intentional (and most of the rest effectively intentional as well).

Off the field, storm clouds were gathering on the horizon. In September 2003 federal agents raided the Bay Area Laboratory Cooperative (BALCO). Run by Victor Conte, BALCO had for years been supplying both legal and illegal performance-enhancing drugs to athletes across the United States. Bonds’ trainer, Greg Anderson, had introduced him to Conte, and when Conte was questioned, federal agents saidhe admitted that he had supplied various steroids to Bonds. Over the next several months story after story would come out about the allegations against Bonds and many other athletes. In November Bonds won his sixth MVP Award, and at the ensuing press conference, asked about PEDs, he denied any knowledge of them. But in December he appeared before a federal grand jury to answer questions under oath about the relationship he had with BALCO.

A year later, in December 2004, the San Francisco Chronicle printed the supposedly secret grand-jury testimony. Bonds had told the grand jury that he used steroids known as the “clear” and the “cream,” but that his trainer, Anderson, told him they were flaxseed oil and rubbing balm.14 A few months later, Kimberly Bell, Bonds’ longtime girlfriend, told the media that she had seen Bonds using steroids. The case against him was damning.

A longtime knee injury had gotten serious enough that Bonds had required multiple surgeries over the winter of 2004-05. He remained in pain and recovery for much of the 2005 season, and it wasn’t until September that he got back on the field for the last couple of weeks of the season. In 2006 he was almost a shadow of his former self, hitting .270 with 26 home runs – he passed Babe Ruth’s 714 in May – but still receiving plenty of walks of both kinds. He came back again in 2007, with the all-time home-run record in his sights. On August 4 in San Diego he tied Hank Aaron with home run number 755, and three days later, on the 7th, he homered off Mike Bacsik of the Washington Nationals to break the record. San Francisco celebrated wildly, as the city did most things Bonds, but the rest of the baseball world was angry that a cheater had broken the sport’s most illustrious record. “It will be the most challenged piece of sport history in memory,” one writer wrote15. The widespread belief was that the record was tainted by steroids, and many had moved on to other things, including baseball itself, which was beginning to crack down on the problem. Bonds celebrated, but after taking the record to 762 by season’s end, discovered that the Giants were not interested in re-signing him. He worked out and was ready to play, but following an indictment for lying to a grand jury he was a pariah in baseball, and no team would take a chance on him.

Bonds finished with many all-time records to his name, not just the home-run title. The all-time leader in walks and intentional walks. (His 688 far exceeded runner-up Aaron’s 293.) Third in runs scored, fourth in total bases, fifth in RBIs. All-time leader in games played as a left fielder. Perhaps most amazingly, most telling about his all-round talent, was that of the eight players with at least 300 stolen bases and 300 home runs, Bonds is not merely the only one with 400 of each but also of 500 each. He was far and away the greatest combination threat of power and speed ever.

Bonds may have expected in his retirement to receive many accolades, and enjoy a long and happy life, but things didn’t work out that way. Legal trouble and baseball trouble would follow.

During his grand-jury testimony in the BALCO case, Bonds had made statements that were ambiguous about receiving steroid injections from Anderson. The prosecutors decided that he was evading their questions, and in November 2007 he was indicted for perjury and obstruction of justice. In 2011 Bonds was convicted on the obstruction charge but the jury deadlocked on the perjury charges. He was sentenced to 30 days of house arrest, along with community service and probation. However, after a series of appeals, in 2015 the conviction was overturned. A federal appeals court decided that although his answers were rambling and evasive, he did not lie on the stand. When prosecutors declined to continue their appeals, the criminal case was over.

That hadn’t helped Bonds’ case with baseball voters, though. His name went on the Hall of Fame ballot for the first time in 2013, and with Roger Clemens also on the ballot, the issue of PEDs climbed into the spotlight. The thought of many was that players who used PEDs should never be allowed into the Hall of Fame, and both Bonds and Clemens suffered in the voting, each receiving just over a third of votes from baseball writers. In the following years his vote total remained very similar, not moving much in either direction. For a player who was almost certainly Hall of Fame level even before he began using steroids, Bonds was clearly being punished by voters. It remained to be seen whether that sentiment would fade, or whether Bonds would be kept out of the Hall of Fame for many years to come.

In recent years Bonds appeared to be trying to change his public image. He regularly posted on social media about events in his life, and tried to present a positive image. Whether that would be sufficient to sway any Hall of Fame voters was doubtful; decades of treating the media badly are difficult to unravel in a short period. Bonds could spend his life beloved in San Francisco but otherwise disliked in public and in baseball, a sad ending for a career that promised so much and delivered on it all, aided perhaps by steroids but also by a strong drive to be the best.

Last revised: December 1, 2015

Photo credits

Barry Bonds, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

Notes

1 Jeff Pearlman, Love Me, Hate Me: Barry Bonds and the Making of an Antihero (New York: HarperCollins, 2006), 28.

2 Pearlman, 15.

3 Pearlman, 35.

4 Pearlman, 48.

5 Hank Hersch, “30/30 Vision: Pittsburgh’s Barry Bonds Sees Those Numbers Coming,” Sports Illustrated, June 25, 1990.

6 Pearlman, 60.

7 Pearlman, 91.

8 “High-risk Bonds now high-performance,” Rockford Register Star, May 16, 1990.

9 “Bonds’ value best in NL,” Boston Herald, November 20, 1990.

10 Pearlman, 142.

11 Ronald Blum, “Bonds wins 4th MVP,” Augusta Chronicle, November 20, 2001.

12 Mark Fainaru-Wada and Lance Williams, Game of Shadows (New York: Gotham Books, 2006), 71.

13 Fainaru-Wada, 72.

14 Fainaru-Wada, 201.

15 Mike Lopresti, “Bonds scandal didn’t have to happen,” Rockford Register Star, March 9, 2006.

Full Name

Barry Lamar Bonds

Born

July 24, 1964 at Riverside, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.